Pigments

Pigments are coloured substances present in most living beings including humans and may be of two broad categories: endogenous and exogenous

Endogenous Pigments:

Endogenous pigments are either normal constituents of cells or accumulate under special circumstances for example, Melanin, alkaptonuria, haemoprotein-derived pigments, and lipofuscin.

Read And Learn More: General Pathology Notes

Melanin:

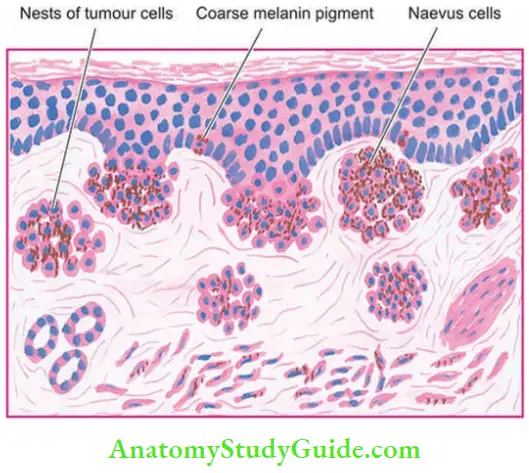

Melanin is the brown-black, non-haemoglobin-derived pigment normally present in the hair, skin, mucosa at some places (for example, oral cavity, oesophagus, anal canal), choroid of the eye, meninges and adrenal medulla.

- In the skin, it is synthesised in the melanocytes and dendritic cells, both of which are present in the basal cells of the epidermis and is stored in the form of cytoplasmic granules in the phagocytic cells called the melanophores, present in the underlying upper dermis.

- Melanocytes possess the enzyme tyrosinase necessary for synthesis of melanin from tyrosine. However, sometimes tyrosinase is present but is not active and hence no melanin pigment is visible.

- In such cases, the presence of tyrosinase can be detected by incubation of tissue section in the solution of dihydroxy phenyl alanine (DOPA).

- If the enzyme is present, dark pigment is identified in pigment cells. This test is called as DOPA reaction and has been used as a stain in the past to differentiate amelanotic melanoma from other anaplastic tumours.

Melanin can be stained with silver dyes such as Masson-Fontana stain while excess of melanin can be bleached oxidising agents such as hydrogen peroxide.

Pigments of the body:

1. Endogenous Pigments:

- Melanin

- Melanin-like pigment

- Alkaptonuria

- Dubin-Johnson syndrome

- Haemoprotein-derived pigments

- Haemosiderin

- Haematin (Haemazoin)

- Bilirubin

- Porphyrins

- Lipofuscin (Wear and tear pigment)

2. Exogenous Pigments:

- Inhaled pigments

- Ingested pigments

- Injected pigments (Tattooing)

Various disorders of melanin pigmentation cause generalised and localised hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation:

Generalised hyperpigmentation:

- In Addison’s disease, there is generalised hyperpigmentation of the skin, especially in areas exposed to light, and of buccal mucosa.

- Chloasma observed during pregnancy is the hyperpigmentation on the skin of face, nipples, and genitalia and occurs under the influence of oestrogen.

- A similar appearance may be observed in women taking oral contraceptives or men treated with oestrogen for prostate cancer.

- In chronic arsenical poisoning, there is characteristic rain-drop pigmentation of the skin.

Focal hyperpigmentation:

- Cäfe-au-lait spots are pigmented patches seen in neurofibromatosis and Albright’s syndrome.

- Freckles are common genetically determined pigmented lesions in fair-skinned individuals similar to cafe-au-lait spots but are smaller.

- Lentigo is a pre-malignant condition in which there is focal hyperpigmentation on the skin of the hands, face, neck, and arms.

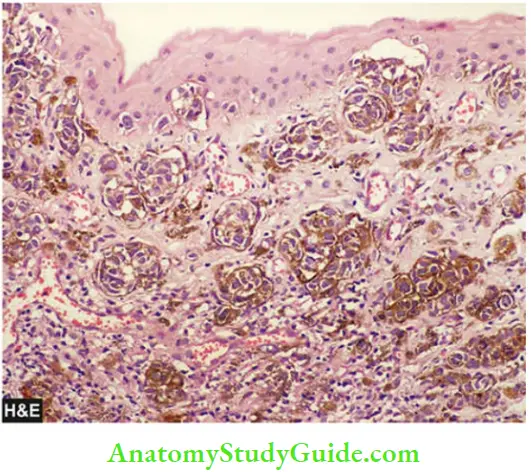

- Melanotic tumours, both benign such as pigmented naevi, and malignant such as melanoma, are associated with increased melanogenesis.

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is characterised by focal peri-oral pigmentation associated with polyps of the intestines.

- Melanosis coli is pigmentation of the mucosa of the colon.

- Dermatopathic lymphadenitis is an example of the deposition of melanin pigment in macrophages of the lymph nodes draining skin lesions.

Generalised hypopigmentation:

Albinism is an extreme degree of generalised hypopigmentation in which the tyrosinase enzyme is genetically deficient and no melanin is formed in the melanocytes.

- Oculocutaneous albinos have no pigment in the skin and have blond hair, poor vision and severe photophobia. They are highly sensitive to sunlight.

- Chronic sun exposure may lead to precancerous lesions and squamous and basal cell cancers of the skin in such individuals.

Localised hypopigmentation:

- Leucoderma is an autoimmune condition with localised loss of pigmentation of the skin.

- Vitiligo is also local hypopigmentation of the skin and is more common. It may have a familial tendency.

- Acquired focal hypopigmentation can result from various causes such as leprosy, healing of wounds, DLE, radiation dermatitis etc.

Melanin-like Pigments:

1. Alkaptonuria:

This is a rare autosomal recessive disorder in which there is a deficiency of an oxidase enzyme required for the breakdown of homogentisic acid; the latter then accumulates in the tissues and is excreted in the urine (homogentisicaciduria).

- The urine of patients of alkaptonuria, if allowed to stand for some hours in the air, turns black due to oxidation of homogentisic acid. The pigment is melanin-like and is termed ochronosis, first described by

- Virchow. It is deposited in both intracellular and intercellular locations, most often in the periarticular tissues such as cartilages, capsules of joints, ligaments and tendons.

2. Dubin-Johnson:

Syndrome Hepatocytes In Patients Of Dubin-Johnson Syndrome, An autosomal recessive form of hereditary conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia, contain melanin-like pigment in the cytoplasm

Haemoprotein-derived Pigments:

Haemoproteins are the most important endogenous pigments derived from haemoglobin, cytochromes and their break-down products.

- For an understanding of disorders of haemoproteins, it is essential to have knowledge of normal iron metabolism and its transport which is described in

- In disordered iron metabolism and transport, haemoproteinderived pigments accumulate in the body.

- These pigments are haemosiderin, acid haematin (haemozoin), bilirubin, and porphyrins.

1. Haemosiderin:

Iron is stored in the tissues in 2 forms:

- Ferritin, which is iron complexed to apoferritin can be identified by electron microscopy.

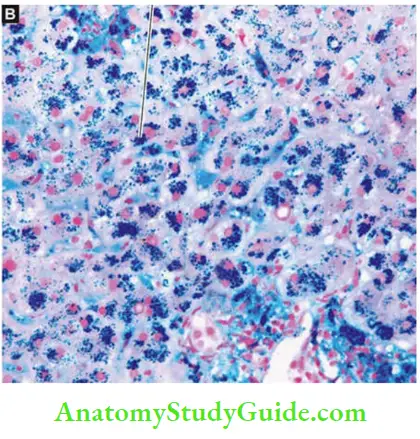

- Haemosiderin, which is formed by aggregates of ferritin and is identifiable by light microscopy as golden-yellow to brown, granular pigment, especially within the mononuclear phagocytes of the bone marrow, spleen and liver where a breakdown of senescent red cells takes place.

- Haemosiderin is a ferric iron that can be demonstrated by Perl’s stain that produces a Prussian blue reaction.

- In this reaction, colourless potassium ferrocyanide reacts with ferric ions of haemosiderin to form deep blue ferric-ferrocyanide.

- Excessive storage of iron in the body may have two morphologic patterns:

- Reticuloendothelial (RE) deposition occurs in the RE cells of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.

- This pattern is seen more often due to multiple blood transfusions or due to excessive administration of parenteral iron.

- Parenchymatous deposition occurs in the parenchymal cells of the liver, pancreas, kidney, and heart.

- This is seen due to genetic and hereditary causes of iron excess in the body, or when iron overload from other causes exceeds the capacity of storage in the RE system.

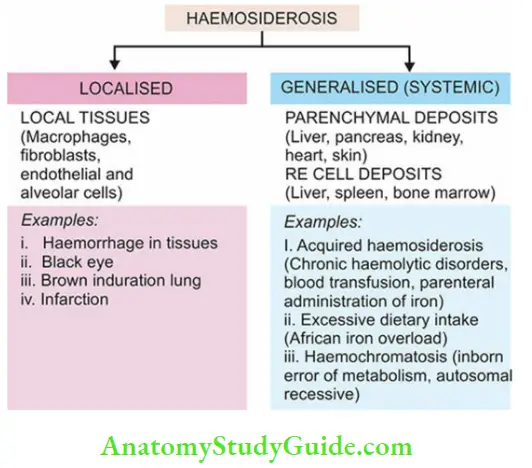

Based on underlying etiology and pathogenesis, excessive storage of iron in the body may result in the following conditions:

- Localised haemosiderosis

- Systemic haemosiderosis

- African iron overload

- Haemochromatosis

Localised haemosiderosis:

This develops whenever there is a haemorrhage in the tissues. With the lysis of red cells, haemoglobin is liberated which is taken up by macrophages where it is degraded and stored as haemosiderin.

A few examples are as under:

- Changing colours of a bruise a black eye or an organising haematoma are caused by pigments like biliverdin and bilirubin which are formed during the transformation of haemoglobin into haemosiderin.

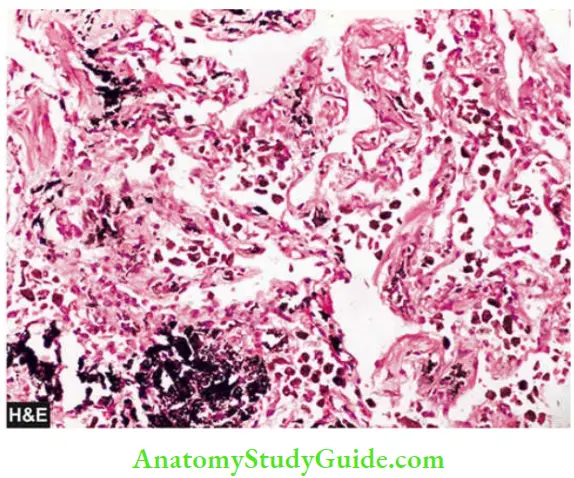

- Brown induration of the lungs as a result of small haemorrhages occurring in mitral stenosis and left ventricular failure.

- Microscopy reveals the presence of ‘heart failure cells’ in the alveoli which are haemosiderin-laden alveolar macrophages.

- Pigmented villonodular synovitis, a tumour-like lesion, in which there are large deposits of haemosiderin in the synovium.

Systemic (Generalised) haemosiderosis:

Systemic overload with iron from the following conditions may result in generalised or systemic haemosiderosis:

- In various forms of chronic haemolytic anaemia (for example., thalassaemia), there is excessive breakdown of red cells and release of excess haemoglobin.

- In multiple blood transfusions and sideroblastic anaemia, there is an excessive load of iron in the body.

- αlcohol-related liver cirrhosis may be complicated by iron overload in the Kupffer cells than in the hepatocytes.

The problem may be further compounded by treating these conditions with blood transfusions (transfusional haemosiderosis) or by parenteral iron therapy.

African iron overload:

The condition was earlier called Bantu siderosis since it was first described in Bantu rural South African communities who consumed alcohol brewed in ungalvanised iron vessels; they had excessive iron absorption and hence iron overload in their body.

- However, subsequently, it was found that a similar type of siderosis also occurred in other individuals of African descent who had no history of such alcohol consumption.

- This led to the identification of a gene, ferroportin, which predisposes to iron overload in such people of African descent hence the name African iron overload.

- The excess iron gets deposited in various organs including the liver where it eventually results in pigment cirrhosis.

Haemochromatosis:

This is a form of iron overload due to excessive intestinal absorption of iron due to an inborn error of metabolism even when the intake is normal. It is a common genetic disorder in the Western population and is inherited as an autosomal recessive pattern.

- It is associated with much more deposits of iron than in haemosiderosis and is largely in the parenchymal cells of the liver, pancreas, heart and kidneys.

- Haemochromatosis is characterised by a triad of features: pigmentary liver cirrhosis, pancreatic damage resulting in diabetes mellitus, and skin pigmentation.

- Based on the last two features, the condition is also termed bronze diabetes.

2. Haematin (Haemazoin):

Haematin or haemazoin, also called malarial pigment, is a haemoprotein-derived brown-black pigment containing haem iron in ferric form in an acidic medium.

- But it differs from haemosiderin because it cannot be stained by Prussian blue (Perl’s) reaction, probably because of the formation of a complex with a protein so that it is unable to react in the stain.

- Haematin pigment is seen most commonly in chronic malaria and in mismatched blood transfusions.

- Besides, the malarial pigment can also be deposited in macrophages and in the hepatocytes.

- Another variety of haematin pigment is formalin pigment formed in blood-rich tissues which have been preserved in an acidic formalin solution.

3. Bilirubin:

- Bilirubin is the normal non-iron-containing pigment present in the bile. It is derived from the porphyrin ring of the haem moiety of haemoglobin.

- The normal level of bilirubin in the blood is less than 1 mg/dl. Excess of bilirubin or hyperbilirubinaemia causes an important clinical condition called jaundice.

- Normal bilirubin metabolism and pathogenesis of jaundice are described in Hyperbilirubinaemia may be unconjugated or conjugated

Accordingly, jaundice may appear in one of the following 3 ways:

- An increase in the rate of bilirubin production due to excessive destruction of red cells (predominantly unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia).

- A defect in handling of bilirubin due to hepatocellular injury (biphasic jaundice).

- Some defects in bilirubin transport within the intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary system (predominantly conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia).

Excessive accumulation of bilirubin pigment can be seen in different tissues and fluids of the body, especially in the hepatocytes, Kupffer cells and bile sinusoids. Skin and sclerae become distinctly yellow. In infants, a rise in unconjugated bilirubin may produce a toxic brain injury called kernicterus.

4. Porphyrins:

Porphyrins are normal pigments present in haemoglobin, myoglobin and cytochrome. Porphyria refers to an uncommon disorder of inborn abnormality of porphyrin metabolism.

- It results from a genetic deficiency of one of the enzymes required for the synthesis of haem, resulting in excessive production of porphyrins.

- Often, the genetic deficiency is precipitated by the intake of some drugs. Porphyrias are associated with the excretion of intermediate products in the urine—delta-aminolaevulinic acid, porphobilinogen, uroporphyrin, coproporphyrin, and protoporphyrin.

Porphyrias are broadly of 2 types—erythropoietic and hepatic:

- Erythropoietic porphyrias: These have a defective synthesis of haem in the red cell precursors in the bone marrow.

- These may be further of 2 subtypes:

- Congenital erythropoietic porphyria, in which the urine is red due to the presence of uroporphyrin and coproporphyrin. The skin of these infants is highly photosensitive.

- Bones and skin show red-brown discolouration.

- Erythropoietic protoporphyria, in which there is an excess of protoporphyrin but no excess of porphyrin in the urine.

- Hepatic porphyrias: These are more common and have normal erythroid precursors but have a defect in the synthesis of haem in the liver. Its further subtypes include the following:

- Acute intermittent porphyria is characterised by acute episodes of 3 patterns: abdominal, neurological, and psychotic. These patients do not have photosensitivity.

- There is excessive delta aminolaevulinic acid and porphobilinogen in the urine.

- Porphyria cutanea tarda is the most common of all porphyrias. Porphyrins collect in the liver and a small quantity is excreted in the urine.

- Skin lesions are similar to those in variegate porphyria. Most of the patients have associated haemosiderosis with cirrhosis which may eventually develop into hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Mixed (Variegate) porphyrias are rare and combine skin photosensitivity with acute abdominal and neurological manifestations.

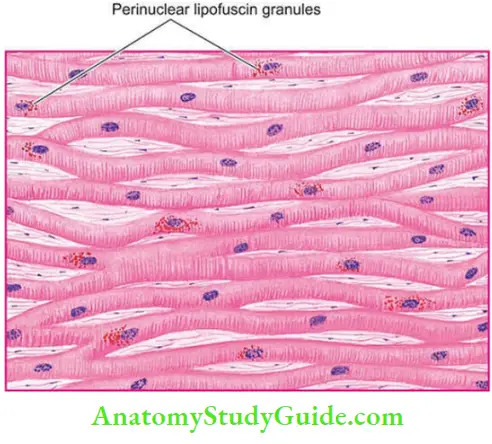

Lipofuscin (Wear and Tear Pigment):

Lipofuscin or lipochrome is a yellowish-brown intracellular, finely granular pigment of lipid protein complex (lipo = fat, fuscus = brown). The pigment is often found in atrophied cells of old age hence the name ‘wear and tear pigment’.

It may be seen in the following conditions:

- Myocardial fibres in brown atrophy of the heart

- Hepatocytes in ageing

- Leydig cells in testicular atrophy

- Neurons in senile dementia

- In wasting diseases unrelated to ageing, when the pigment may accumulate rapidly in different cells.

Unlike in normal cells, in ageing or debilitating diseases the phospholipid end-products of membrane damage mediated by oxygen free radicals fail to get eliminated by intracellular lipid peroxidation.

These, therefore, persist as collections of indigestible material in the lysosomes; thus lipofuscin is an example of residual bodies.

- By light microscopy: The pigment is coarse, golden-brown granular and often accumulates in the central part of the cells around the nuclei. In the heart muscle, the change is associated with wasting of the muscle and is commonly referred to as ‘brown atrophy’. The pigment can be stained by fat stains but differs from other lipids in being fluorescent and having positive acid-fast staining.

- By electron microscopy: lipofuscin appears as intralysosomal electron-dense granules in a perinuclear location.

Exogenous Pigments:

Exogenous pigments are the pigments introduced into the body from outside such as by inhalation, ingestion or inoculation.

Inhaled Pigments:

The lungs of most individuals, especially those living in urban areas due to atmospheric pollutants and of smokers, show a large number of inhaled pigmented materials.

- The most commonly inhaled substances are carbon or coal dust; others are silica or stone dust, iron or iron oxide, asbestos and various other organic substances.

- The pigment particles after inhalation are taken up by alveolar macrophages.

- Some of the pigment-laden macrophages are coughed out via bronchi, while some settle in the interstitial tissue of the lung and in the respiratory bronchioles and pass into lymphatics to be deposited in the hilar lymph nodes.

- Anthracosis (i.e. deposition of carbon particles) is seen in almost every adult lung and generally provokes no reaction of tissue injury.

- However, extensive deposition of particulate material over many years in coal miners’ pneumoconiosis, silicosis, asbestosis etc. provoke low-grade inflammation, fibrosis and impaired respiratory function.

Ingested Pigments:

Chronic ingestion of certain metals may produce pigmentation. The examples are as under:

- Argyria is chronic ingestion of silver compounds and results in brownish pigmentation in the skin, bowel, and kidney.

- Chronic lead poisoning may produce the characteristic blue lines on teeth at the gum line.

- Melanosis coli results from prolonged ingestion of certain cathartics.

- Carotenaemia is a yellowish-red colouration of the skin caused by excessive ingestion of carrots which contain carotene.

Injected Pigments (Tattooing):

Pigments like Indian ink, cinnabar and carbon are introduced into the dermis in the process of tattooing where the pigment is taken up by macrophages and lies permanently in the connective tissue.

Examples of injected pigments are prolonged use of ointments containing mercury, dirt left accidentally in a wound, and tattooing by pricking the skin with dyes.

Pigments:

- Pigments may be endogenous in origin or exogenously introduced in the body.

- The most common endogenous pigment is melanin. Disorders of melanin are due to defects in tyrosine metabolism and may give rise to hyper- and hypopigmentation, each of which may be generalised or localised.

- Haem-derived pigments are haemosiderin, haematin, bilirubin and porphyrin.

- Excess of haemosiderin may get deposited in local tissues, or as generalised deposits in the reticuloendothelial tissues and in parenchymal cells.

- Haemosiderin in tissues stains positive for Perl’s Prussian blue stain.

- Haemosiderosis is the excessive local or systemic excess deposition of iron in the body due to acquired causes, while haemochromatosis is due to excess iron deposition from genetic and hereditary causes.

- Haemazoin is an acid haematin or malarial pigment which is negative for Perl’s Prussian blue stain.

- Bilirubin is a non-iron-containing pigment; its increase (conjugated or unconjugated) in the blood causes jaundice.

- Bilirubin in the blood may rise from its increased production, hepatocellular disease or obstruction in its excretion.

- Porphyrias are due to inborn errors in porphyrin metabolism for haem synthesis.

- Lipofuscin is a golden brown intralysosomal pigment seen in ageing and in debilitating diseases; it is an expression of residual bodies or wear and tear pigment.

- Exogenous pigments may appear in the body from inhalation (Carbon dust), ingestion and tattooing

Leave a Reply