Dental Traumatology An Overview Introduction

Dental traumatology requires more attention and profound discussion in paediatric dentistry as dental and orofacial trauma is being encountered commonly, especially in children.

Table of Contents

An injury to teeth, oral soft tissues and associated hard tissues has significant short-term and long-term consequences.

A fracture of a tooth causes short-term consequences whereas a fracture of the jaw along the line of tooth buds causes long-term consequences.

The injury is bound to have emotional implications for the child as well.

Read And Learn More: Paediatric Dentistry Notes

Dental/orofacial trauma can involve the teeth, with/without alveolar bone, basal jaw bones (maxilla and mandible), lips and other oral soft tissues.

When the injury involves the face, it may consist of trauma to the nasal bone, to the zygomatic arch and less commonly to the temporal bone.

Prompt emergency care, understanding of the mechanism of trauma, diagnosis of the magnitude and extent of trauma, appropriate definitive therapy, forecast of long-term implications and a strategic follow-up are fundamentals of dental traumatology.

The commonly followed classification of dental/orofacial trauma, aetiopathogenesis and epidemiology of dental trauma are discussed in this chapter.

Classification:

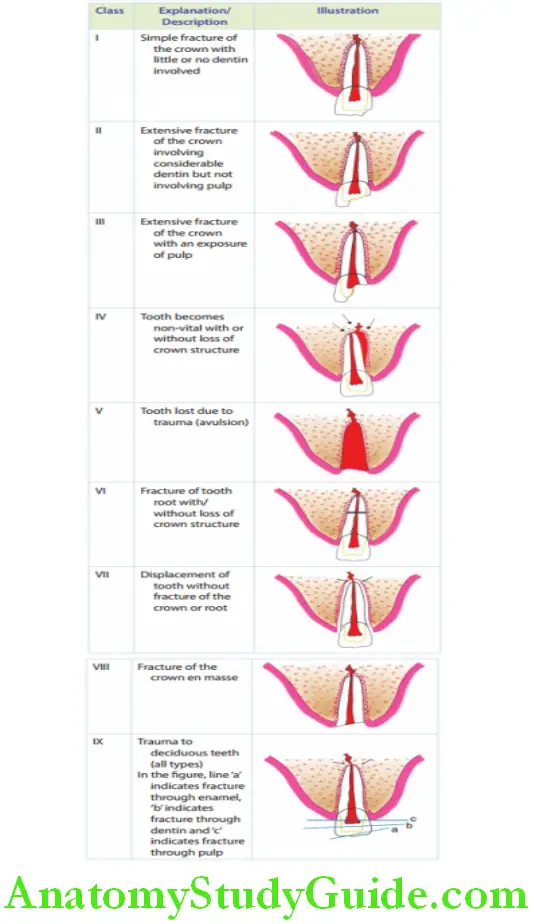

Traumatic injuries to teeth and associated structures have been classified by Ellis and Dewey in 1960 and by Andreasen in 1981.

The table gives Ellis and Dewey’s classifications of dental trauma. An edited version of Andreasen’s classification (discussed in this chapter) has been adopted by WHO.

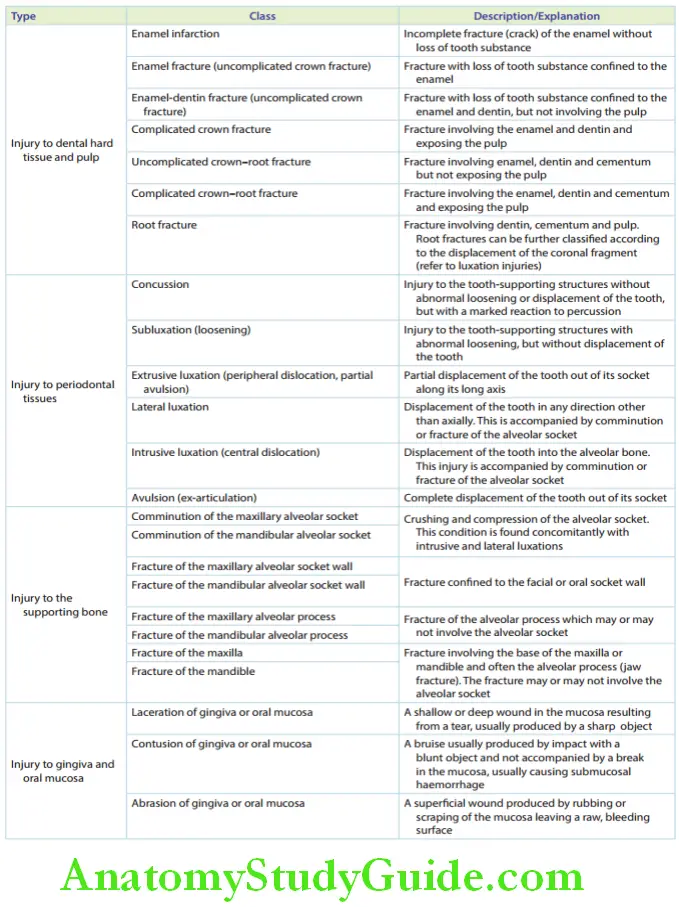

Andreasen’s Classification Of Dental Trauma

Andreasen’s classification of dental trauma has four major classes, which are further subdivided into minor classes of injuries.

Ths classifiation has universal pertinence. It is very helpful in paediatric dentistry as it is applicable to primary dentition, mixed dentition and permanent dentition.

The four major classes are as follows:

- Injury to hard dental tissues and pulp

- Injury to the periodontal tissues

- Injury to the supporting bone

- Injuries to the gingiva and oral mucosa

Aetiopathogenesis:

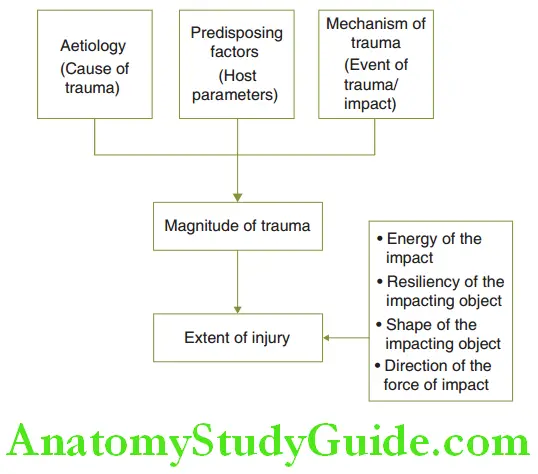

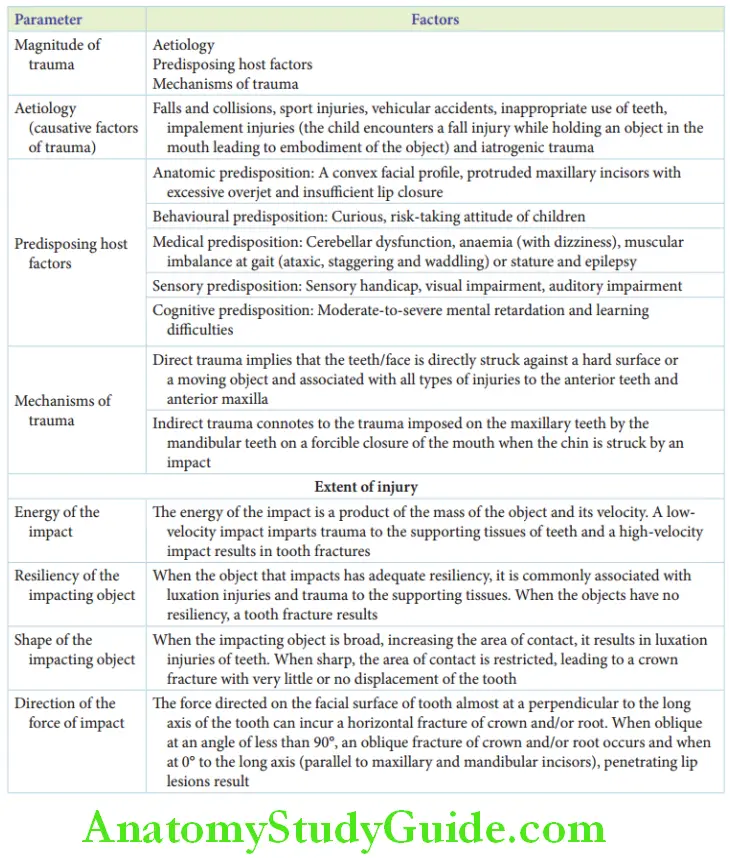

The aetiopathogenesis of traumatic dental injuries requires the description of three important parameters, which are as follows:

- Aetiology: Cause of trauma

- Predisposing factors: Host parameters

- Contributing mechanisms: Event of trauma and impact

The combination of these parameters decides the magnitude of trauma and the extent of the injury.

1. Aetiology: The cause of traumatic dental injuries can be broadly classified into intentional and non-intentional. Intentionally inflicted trauma is otherwise called child abuse.

Unintentional causes are as follows:

Fall and collision: Fall injuries are common in 2-year-old children, especially when they learn to walk. This is described as a ‘toddler fall injury’.

Collisions or colliding with each other or with other objects are common in school-going children.

Sports injuries: Sports such as rugby ice hockey and martial arts can be described as high-risk sports.

The low-risk sports include cricket, basketball, squash and diving. Contact sports such as boxing and wrestling commonly induce trauma.

Vehicle accidents: Vehicular accidents range from a simple fall from the cycle to a major automobile collision. Major accidents result in multiple orofacial injuries.

Inappropriate use of teeth: Trauma injuries to the teeth and oral soft tissues can be induced by inappropriate use of teeth such as attempting to open a corked bottle, a hair clip or a packet of snacks.

Pen/pencil biting, cutting or holding objects with teeth or attempting to repair broken toys and gadgets with teeth can also cause trauma.

Impalement injuries: These are injuries in which foreign bodies that have induced the trauma are partially or completely implanted into the soft tissue.

These occur when a child falls while holding an object in the mouth. Common objects associated with impalement injuries are toothbrushes, small wooden sticks and pencils.

Impalement injuries can result in moderate to severe deep injuries and they have the potential to end in lethal complications too. They are common in toddlers.

Iatrogenic trauma: Iatrogenic or physician/ anaesthetist/dentist-induced trauma can happen during the following conditions:

- Prolonged oral intubation

- Inappropriate/hasty intubation/detubation

- The head of the handpiece striking the incisors during movement

The trauma inflicted thus may vary from a hairline fracture of enamel to en masse crown fracture or an avulsion of the tooth involved depending on the character and velocity of the object involved.

2. Predisposing factors: The host parameters that predispose the child to orofacial trauma can be broadly classified into the following categories:

- Anatomic predisposition: Convex facial profile, protruded maxillary incisors with excessive overjet and insufficient lip closure may cause a traumatic injury.

- Behavioural predisposition: Children with curious, risk-taking attitudes are reported to encounter trauma more often.

- Cognitive predisposition: Children with moderate to severe mental retardation and learning difficulties are more vulnerable to orofacial trauma compared to their normal counterparts.

- Medical predisposition: Children with cerebellar dysfunction, anaemia with associated dizziness, ataxic or a staggering gait, muscular imbalance and epilepsy are more prone to fall-/collision-related dental injuries.

- Sensory predisposition: There is a higher rate of incidence of trauma in children with sensory handicaps such as visual impairment and auditory impairment.

3. Mechanism of trauma: Traumatic dental injuries can be direct or indirect in nature. Direct trauma implies that the teeth/face is directly struck against a hard surface or a moving object.

Indirect trauma connotes the trauma imposed on the maxillary teeth by the mandibular teeth due to a forcible closure of the mouth when the chin is struck by an impact.

Direct trauma is associated with all types of injuries to the anterior teeth and anterior maxilla while indirect trauma commonly results in crown/crown–root fractures of premolars or molars and fracture of the condyle, symphysis or para symphysis.

Magnitude Of Trauma/Extent Of Injury

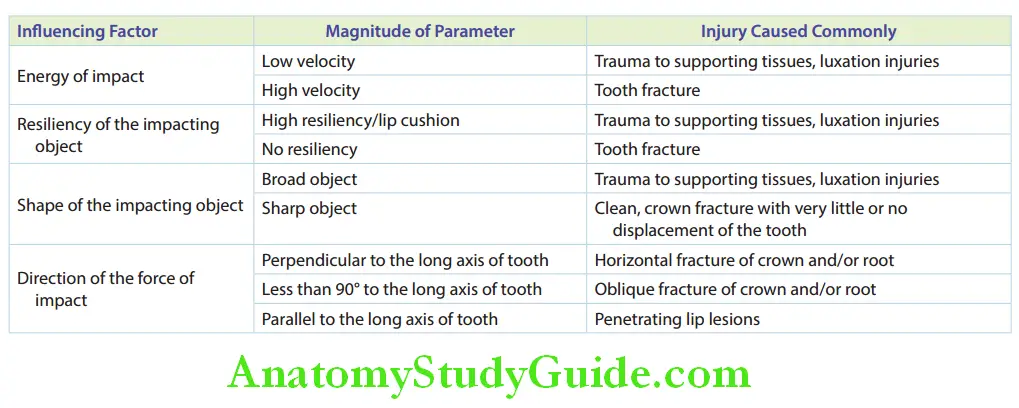

The magnitude of trauma completely influences the extent of the injury. It is dependent on the following four factors:

1. The energy of the impact: This is a product of the mass of the object and its velocity. A moving cricket ball involves less mass with a relatively high velocity.

A fall against the ground involves very high mass with negligible velocity.

Low-velocity impact imparts trauma to the supporting tissues of teeth and results in luxation injuries of teeth. High-velocity impact results in tooth fractures more commonly.

2. The resiliency of the impacting object: When the object that impacts has adequate resiliency (like a tennis ball), or when the lip cushions the incisors during the impact, a portion of the energy is absorbed by the cushion (either the object or the lips).

The rest of the force is diffusely distributed. Such an event more commonly causes luxation injuries and trauma to the supporting tissues.

In the event of no resiliency of the object (such as a stone landing directly onto an incisor), no portion of the energy is absorbed. The energy is concentrated on the tooth hit and commonly results in a tooth fracture.

3. The shape of the impacting object: When the impacting object is broad, increasing the area of contact, it results in a dull, diffuse injury to the supporting structures. It causes luxation injuries of teeth.

When the object is sharp, the area of contact is restricted to a point or a line. This focuses on the impact leading to a clean, crown fracture with very little or no displacement of the tooth.

4. Direction of the force of impact: The force is most commonly directed on the facial surface of the tooth almost perpendicular to the long axis of the tooth.

This direction of force application can cause a horizontal fracture of the crown and/or root. When the direction of impact makes an angle of less than 90° (due to a hard, fling object such as a cricket ball), an oblique fracture of the crown and/or root is encountered.

When the direction of impact makes 0° with (i.e. parallel to) the long axis of maxillary and mandibular incisors, penetrating lip lesions are encountered.

Enamel can be fractured by a force parallel to the enamel rods. Dentin can be fractured by a force perpendicular to the dentinal tubules.

Conclusively, the aetiology, predisposing factors and mechanism of trauma determine the magnitude of trauma which in turn describes the extent of injury.

Epidemiology:

The oral region comprises only 1% of the total body area but it has been involved in 5–33% of all traumatic injuries.

Trauma in boys is twice more common than in girls. However recent studies have reported a significant reduction in this difference.

The common age of occurrence of traumatic injuries shows two peak periods, which are as follows:

Between 2 and 4 years: Toddler fall injuries are the most prevalent. This is when children are in the process of learning to walk unaccompanied.

Between 8 and 10 years: Sport-related injuries are more common. Children are curious; they have an experimental attitude and are involved in active play.

The most commonly affected teeth in primary and permanent dentitions are maxillary central incisors followed by maxillary lateral incisors.

Luxation injuries (intrusive, extrusive and lateral luxation) and avulsion are the predominant types of traumatic injuries in the primary dentition.

This is due to the increased periodontal ligament thickness of primary teeth and the increased pliability and resiliency of the primary alveolar bone. Tooth fractures are very uncommon in primary teeth.

However, in mixed dentition, tooth fractures are much more common than displacement or luxation injuries in permanent teeth.

The alveolar bone around permanent teeth is more compact, less pliable and resilient with smaller alveolar spaces. Hence, it resists displacement of teeth.

An avulsion is common in newly erupted permanent teeth following a dull trauma to the supporting alveolar bone. This is because the (existing) formed root length is only half to two-thirds.

The locations where most dental traumas occur are homes followed by schools and playgrounds and to a lesser extent in streets and public places.

More traumatic injuries have been reported during the winter months. This variation may be explained as more school holidays are scheduled in winter months possibly increasing the outdoor playtime of children.

Diagnosis Of Dental Trauma

Emergency care and definitive treatment for orofacial dental trauma are most appropriate when the traumatic mechanism, extent and magnitude of the traumatic injury are well understood. These parameters are essential for the diagnosis of the traumatic injury.

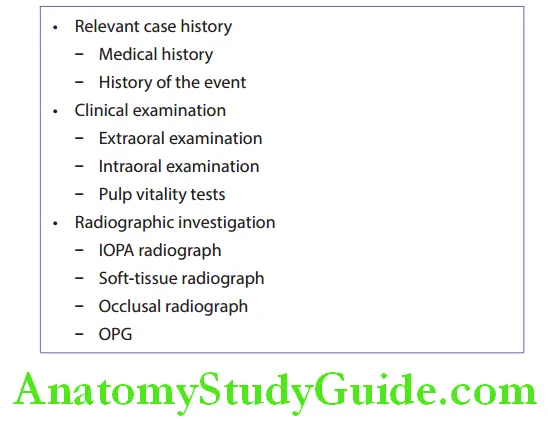

Diagnosis of the injury involves the following parameters:

- Obtaining a relevant case history

- Clinical examination

- Extraoral examination

- Intraoral examination

- Pulp vitality tests

- Radiographic investigation

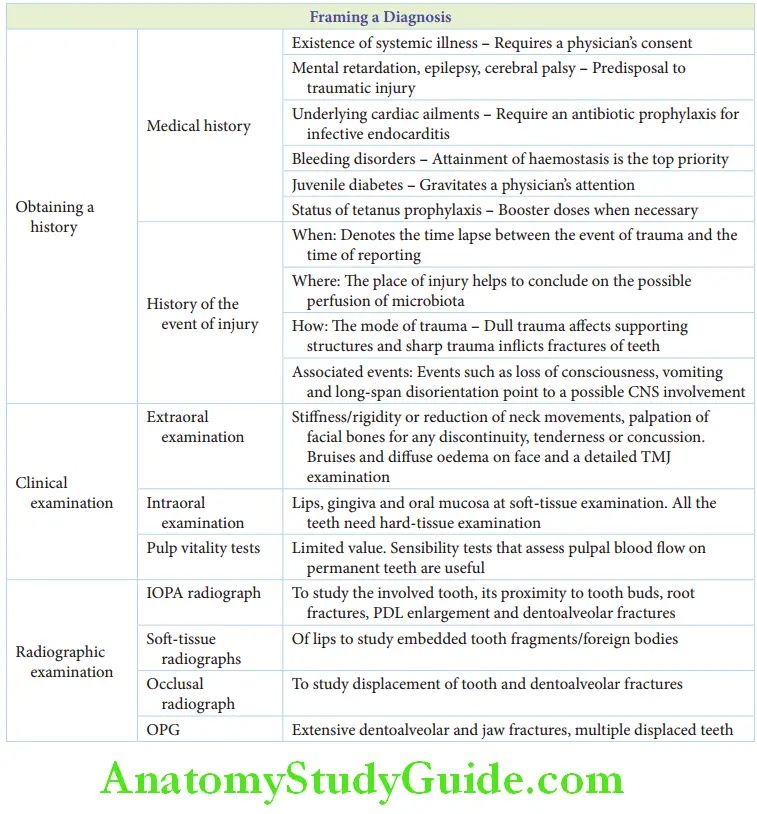

Case History:

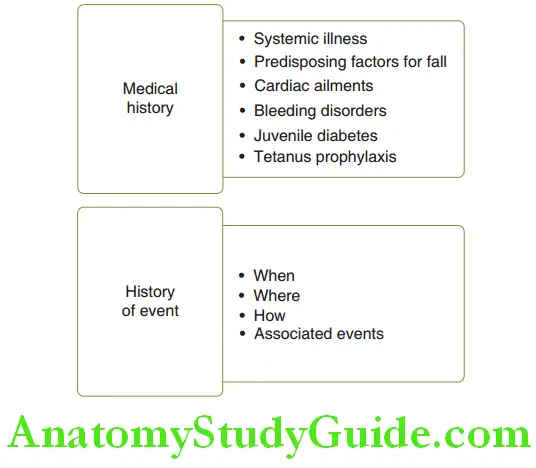

Obtaining relevant case history means knowing the medical history of the patient and the history of the event of injury. The medical history has to be obtained in a structured manner.

It may reveal the following details:

The existence of systemic illness that would require the physician’s consent and intervention for treatment

Mental retardation, epilepsy, cerebral palsy and other predisposing factors to acquire a fall injury

Underlying cardiac ailments that would require antibiotic prophylaxis to avoid infective endocarditis

Bleeding disorders that would require primary attention than the injury per se. Attainment of haemostasis and making blood replacements available, if required, hold the top priority in such cases

Juvenile diabetes and reported allergies to certain antibiotics/medication would necessitate the physician’s attention

The status of tetanus prophylaxis would help in deciding the requirement of a booster dose.

If the child is younger than 5 years and a regular immunisation schedule is followed, a booster dose may not be required.

If the child is older than 5 years and no dose was administered in the last 6 months, then a booster dose becomes necessary.

The history of the event of injury can be revealed with the help of four iconic parameters, which are as follows:

1. When: It denotes the time lapse between the event of trauma and the time of reporting to the clinician.

A lapse of 24 hours for pulpal exposure and a lapse of 6 hours for avulsion injuries have a fair-to-poor prognosis.

2. Where: The place of injury helps to find out the possible perfusion of microbiota (fall from a diving board into a swimming pool), the need for tetanus prophylaxis (a bicycle accident on a road) and another serious associated injury (possible head injury).

3. How: The mechanism of trauma is the most important of the four parameters to throw light on the severity of the injury. Dull trauma affects supporting structures and sharp trauma inflicts fractures of teeth.

4. Associated events: Events such as loss of consciousness, vomiting and long-span disorientation point to a possible central nervous system injury.

The symptoms may arise 3–4 hours after trauma. In such cases, the child should be kept under direct observation for 24 hours, which includes waking him every 2–3 hours at night to rule out possible head injury.

Clinical Examination:

During clinical examination, it may be highly tempting to locate and look deeper into the tissue/tooth most affected.

However, a strategic examination course has to be followed. It involves the extraoral and intraoral examination followed by vitality tests.

1. Extraoral examination: Stiffess/rigidity or reduction of neck movements is enough to suspect a cervical injury, which requires a physician’s intervention. All the facial bones have to be palpated for any discontinuity or tenderness.

Discontinuity denotes a possible fracture and tenderness denotes a concussion at the site. Bruises and diffuse oedema have to be recorded.

The temporomandibular joint has to be palpated and mandibular movements have to be assessed to rule out an involvement of the joint.

2. Intraoral examination: This involves the soft tissue and hard-tissue examination.

Soft-tissue examination: Lips are the most commonly affected site during orofacial trauma. Embedded fragments of foreign bodies, soil fragments or tooth fragments should be looked for.

A through-and-through penetration of the lip by any foreign body has to be identified. The mucoperiosteum may be stripped of the bone at the junction between the attached and the free gingiva.

Such an injury is termed ‘degloving injury’.

Hard-tissue examination: Each tooth in the mouth has to be examined for the following:

- A craze/hair-line fracture

- Crown fracture

- Pulp exposure

- Displacement (luxation)

- The direction of displacement (intrusive, extrusive or lateral luxation)

- Mobility

Avulsed teeth (if any) have to be recorded and they need primary attention. Teeth with no fracture or displacement may be highly tender to touch. Such teeth are said to have undergone a concussion injury.

The alveolar bone should be palpated for a step defect which implies a fracture line. Ecchymoses on soft tissues demonstrate a haematoma.

Pulp vitality tests: Primary teeth do not give reliable results for pulp vitality tests. A child may be too immature to comprehend meaningfully.

The child, having experienced trauma, may be restless and anxious. Recently traumatised teeth do not elicit a response.

Hence, pulp vitality tests are of no importance in the diagnosis of recently traumatised primary teeth.

Permanent teeth in mixed dentition, that is recently traumatised, young permanent teeth, do not give a reliable response.

However, sensibility tests such as laser Doppler flowmetry, transmitted light photoplethysmography and pulse oximetry are highly useful in studying recently traumatised, young permanent teeth.

They can differentiate between normal blood flow, increased blood flow (hyperaemia) and decreased blood flow (stasis) in pulpal blood vessels.

An increase in blood flow will occur in a tooth that is recently traumatised or in a tooth with inflamed pulp tissue.

A decreased blood flow is observed in teeth with a degenerating pulp, which is progressing into a phase of necrosis from the phase of inflammation.

Radiographic Investigation:

Radiographs used for primary diagnosis are also useful as baseline data for further follow-up. They are useful in predicting the long-term prognosis of the injured tooth/tissues.

Radiographs that may be indicated to reveal the trauma and affected areas are as follows:

1. IOPA radiograph: It is useful to study the proximity of the tooth bud, the presence of a root fracture, the extent of a fracture line into the root, enlarged periodontal ligament space and dentoalveolar fractures.

2. Softtissue radiographs with an IOPA fim: Softissue radiographs, most commonly of the lip, identify any embedded tooth fragments or foreign bodies.

3. Occlusal radiograph: An occlusal radiograph is useful to study the displacement of multiple teeth in the arch and the existence of dentoalveolar fractures.

4. OPG: It is indicated when extensive dentoalveolar or jaw fractures are suspected or else when multiple teeth are displaced.

Treatment Outline:

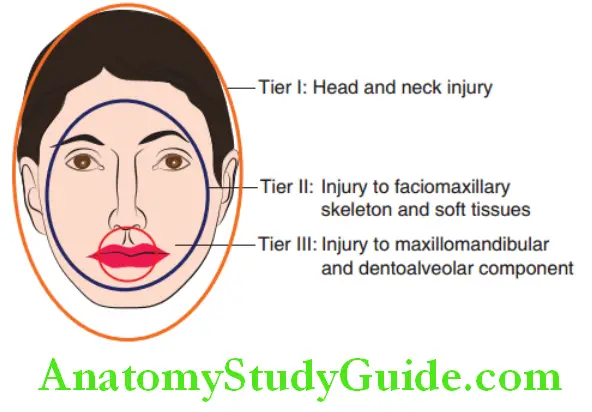

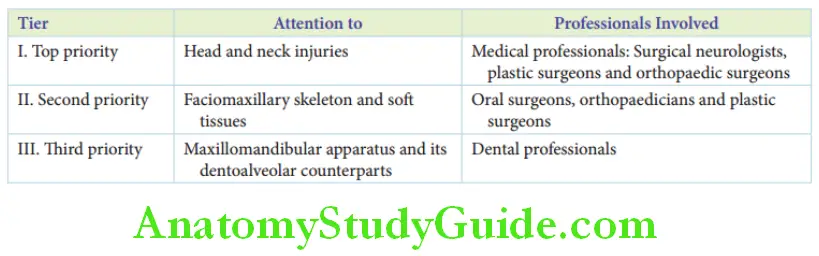

The outline of the treatment of orofacial trauma is fundamentally based on a three-tier priority pattern. The top priority is given to the outer circle.

The head and neck injuries have to be attended to first to prevent potentially lethal complications and stabilise the patient’s vital signs and general orientation.

This care is rendered by medical professionals, namely surgical neurologists, plastic

surgeons and orthopaedic surgeons.

The second priority is given to the second largest circle. Injuries to the faciomaxillary skeleton and soft tissues are attended to at the next level.

This care requires medical as well as dental professionals, namely oral surgeons, orthopaedics and plastic surgeons.

The third priority is given to the maxillomandibular and the dentoalveolar components. This part is solely handled by dental professionals.

Specific definitive treatment of soft and hard tissues of primary/permanent dentition is discussed in Chapters 57–60.

Summary

1. Dental and orofacial trauma is common in children and can involve teeth, with/without alveolar bone, basal jaw bones, lips and other oral soft tissues. The nasal bone, zygomatic arch and less commonly the temporal bone are facial bones that are involved.

2. Traumatic injuries to teeth and the associated structures have been classified by Ellis Dewey and Andreasen.

3. Aetiopathogenesis of traumatic dental injuries:

4. Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries:

- Though the oral region comprises only 1% of the total body area, however, it has been involved in 5–33% of all traumatic injuries.

- Trauma in boys is twice more common than in girls.

- The age of occurrence depicts two peak periods – 2 to 4 years and 8 to 10 years.

- The most commonly affected teeth in both dentitions are maxillary central and lateral incisors.

- Luxation injuries and avulsion are the predominant types of traumatic injuries in the primary dentition.

- Tooth fractures are much more common than displacement (luxation) injuries with permanent teeth in mixed dentition.

- Avulsion injury is more commonly encountered in newly erupted permanent teeth.

- The most common location of infection of dental trauma is at home.

- More traumatic injuries are reported during the winter months.

5. Framing a diagnosis of the traumatic injury

6. The treatment outline is fundamentally based on a three-tier priority pattern

Leave a Reply