Hepatitis Viruses

Hepatitis viruses are heterogeneous group of viruses that are taxonomically diverse (belong to different families) but all are hepatotropic; cause acute inflammation of the liver producing identical histopathologic lesions and similar clinical illnesses such as fever, nausea, vomiting, and jaundice.

Table of Contents

- Hepatitis viruses are classified into six types: (HAV, HBV, HCV, HDV, HEV, and HGV).

- Other viruses that can cause sporadic hepatitis, are yellow fever virus, CMV, EBV, HSV, rubella virus, and enteroviruses.

Read And Learn More: Micro Biology And Immunology Notes

Hepatitis A Virus

Hepatitis A virus belongs to the family Picornaviridae (called enterovirus 72 or genus Hepatovirus)

HAV is 27 to 32 nm in size, with icosahedral symmetry, containing a linear ssRNA.

Epidemiology

- Mode of transmission

- HAV transmission is by the fecal-oral route

- Rarely, by sexual (oro-genital contact) and parenteral routes.

- Hosts: Humans are the only hosts for HAV.

- Age:

- Children and adolescents (5–14 years of age) are MC affected, the majority remain subclinical (80–95%)

- However, in developed countries with improved hygiene, the incidence is decreasing and there is a trend to shift of infection towards the older age.

- Adults are more icteric (75–90%), with a higher mortality rate than children.

- Anicteric to icteric cases: ratio is about in children – 12:1 and in adults – 1:3.

- Risk factors: Poor personal hygiene and overcrowding. In developing countries, most of the children (90%) are infected by the age of 10 years.

- Seasonality: Widespread throughout the year (peak in late rainfall and in early winter).

- Virus excretion: Viral excretion in feces maybe 2 weeks before to 2 weeks after the appearance of jaundice.

- Outbreaks are common in summer camps, daycare centers, families and institutions, neonatal ICUs, and among military troops.

- Recurrent epidemics and sudden, explosive epidemics are common following fecal contamination of a single source (e.g. drinking water, milk, or food such as raw vegetables, salad, frozen strawberries, green onions, and shellfish).

Laboratory Diagnosis

- Anti-HAV Antibody detection

- IgM antibodies appear during the acute phase, peak about 2 weeks after the elevation of liver enzymes, and disappear within 3–6 months.

- IgG appears a week after the appearance of IgM, persists for decades, and indicates past infection or recovery.

- Detection of HAV particles by immune electron microscopy: HAV appears in stool from -2 to +2 weeks of jaundice

- Detection of HAV antigens in stool by ELISA from -2 to +2 weeks of jaundice

- Isolation: HAV is the only hepatitis virus where isolation has been attempted though difficult (primate cell lines)

- Non-specific: Elevated liver enzymes and serum bilirubin level.

Vaccines

- Formaldehyde inactivated vaccine: It is prepared from human fetal lung fibroblast cell lines, given by IM

- Live attenuated vaccine: It uses H2 and L-A-1 strains, prepared in a human diploid cell line (China)

- Both vaccines are highly immunogenic and produce long-lasting immunity.

HAV-Ig

It is useful for post-exposure prophylaxis of intimate contacts (household, day care centers) of persons with hepatitis A or to travelers.

It should be administered within 2 weeks of exposure and gives protection for 1–2 months.

Hepatitis B Virus

The Hepatitis B virus is the most widespread hepatitis virus.

HBV is the only DNA virus among hepatitis viruses; discovered by Blumberg in 1963 and belongs to the family Hepadnaviridae.

Morphology

Electron microscopy of the serum of the patients infected with HBV reveals 3 morphologic forms:

- Spherical form: Most numerous, (22 nm size), exclusively made up of HBsAg.

- Tubular or filamentous form: 200 nm long, also exclusively made up of HBsAg.

- Complete form or Dane particles: They are less frequently observed, 42-nm size spherical virions; made up of-

- Outer surface envelope: HBsAg (Hepatitis B surface antigen or envelope antigen or Australian antigen).

- Inner 27 nm size nucleocapsid: Consists of core antigen (HBcAg) and pre-core antigen

(HBeAg) and DNA polymerase.

Viral Genome

- The S gene has three regions: S, pre-S1, and pre-S2. They code for surface antigens (HBsAg).

- C gene: Consists of pre-C and C-regions, which code for two nucleocapsid proteins

- Pre-C region codes for HBeAg

- C-region codes for HBcAg

- X gene codes for HBxAg.

- It may contribute to carcinogenesis by binding to p53.

- HBxAg and its antibody are elevated in patients with severe chronic hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

- P gene is the largest and codes for polymerase (P) protein, having 3 enzymatic activities: (1) DNA polymerase activity, (2) Reverse transcriptase activity, and (3) RNase H activity.

Typing of HBV

Serotypes: HBV is divided into four major serotypes (adr, adw, ayr, ayw) based on antigenic epitopes present on its envelope protein HBsAg.

- ADW is the predominant subtype in Europe, Australia, and America

- In India ADR is the prevalent subtype in South and East India whereas ayw is prevalent in Western and Northern India.

Genotypes: Has eight genotypes (A–H). Genotypes A and D are prevalent in India.

Hepatitis B Virus Mutants

Pre-core Mutants

- They have defects in a pre-core region of the C gene which leads to their inability to synthesize HBeAg.

- Geographical distribution: Identified in Mediterranean countries and Europe.

Such patients may be diagnosed late and they tend to have severe chronic hepatitis that progresses to cirrhosis. - Markers: They lack HBeAg. Other viral markers are present as such.

- BCP mutation: Mutation in basal core promoter region is common with HBV genotype C and is associated with risk for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Escape Mutants

They have mutations in the S gene, which leads to the alteration of HBsAg (usually in an antigen). They may pose problems in hepatitis B vaccination strategies as well as in the diagnosis of the disease.

These mutations are observed in:

- Infants born to HBeAg-positive mothers

- Liver transplant recipients.

- A small proportion of recipients of active and passive immunization.

- Underdiagnosed: Patients infected with escape mutants lack HBsAg and therefore are often underdiagnosed by routine serological tests for HBsAg

- Vaccine failure: Escape mutants are capable of causing infection in vaccinated individuals as anti-HBs present in them cannot neutralize these HBsAg negative mutants.

YMDD Mutation

HBV-infected patients on lamivudine therapy may develop resistance to the drug due to mutation in the YMDD locus of the HBV reverse transcriptase region of the polymerase gene.

Transmission

HBV transmission occurs via multiple routes.

- Parenteral route: In developing countries, the most common mode of transmission is via blood and blood products transfusion and needle prick injuries.

- The transmission risk of HBV following needle prick injury is nearly 30% as compared to 3% and 0.3% with HCV and HIV respectively. As little as 0.00001 ml of blood can be infectious for HBV.

- Sexual transmission is the most common route in developed countries. (homosexual males)

- Vertical (perinatal) transmission: Particularly in China and SE Asia.

- Transmission occurs at any stage; in utero, during delivery (maximum risk), and during breastfeeding

- Risk is maximum if the mother is HBeAg positive.

- Direct skin contact with infected open skin lesions, e.g. impetigo (especially in children).

Epidemiology

Hepatitis B virus infection occurs throughout the world.

- Reservoir of infection: Humans are the only reservoir of infection who can be either cases or carriers. Carries may be temporary (harbor the virus for weeks to months) or persistent/chronic (harbor the virus for > 6 months).

- Carriers can also be grouped into:

- Simple carriers (or chronic inactive HBV infection): They are of low infectivity, and transmit the virus at a lower rate. They possess a low level of HBsAg and no HBeAg

- Supercarriers (or Immunotolerant chronic HBV infection): They are highly infectious and transmit the virus efficiently.

They possess higher levels of HBsAg and also have HBeAg, DNA polymerase, and HBV DNA.

- Prevalence: Based on HBsAg carrier rates, three epidemiological patterns are observed:

- Low endemicity: The carrier rate is less than 2%. It is observed in many countries in America, European regions, and Australia. The lowest is recorded for the UK and Norway (0.01%)

- Intermediate endemicity: The carrier rate is between 2 and 8%. It is observed in India, China, and many countries of the Eastern Mediterranean and Southeast Asian regions

- High endemicity: The carrier rate is more than 8%. It is observed in many countries of African and Western Pacific regions.

Some countries exceed HBV prevalence of >15% such as South Sudan, Kiribati, Swaziland, and Solomon Islands.

- Situation in the world: WHO estimates that in 2015, about 257 million population were living with chronic HBV infection with a global prevalence of 3.5%. The widespread use of the HBV vaccine in infants has led to a considerable reduction in the incidence of new chronic HBV infections.

- Situation in India: India is considered to have an intermediate level of HBV endemicity(3.7% prevalence); with over 40 million HBV carriers, which constitutes 11% of the estimated global burden, which is second highest to China (30%)

- The highest prevalence was recorded in Andamans and Arunachal Pradesh

- In tribal areas, the prevalence is extremely high (19%) than non-tribal populations

- HBV accounts for 40–50% of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and 10–20% of cirrhosis in India.

- Elimination of viral hepatitis: The WHO has introduced a Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis (2016–2021) which aims at the elimination of viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030 (defined by reducing new infections by 90% and mortality by 65%).

World Hepatitis Day is celebrated on 28th July every year. - Resistance: HBV can be destroyed by hypochlorite and heat (by autoclaving)

- Period of infectivity: Infectious as long as the HBsAg is present in the blood, i.e. during the incubation period (a month before jaundice) up to several months thereafter (occasionally years for chronic carriers).

- Become non-infectious once HBsAg disappears and is replaced by anti-HBs antibody.

- Maximum infectivity is observed when HBeAg is elevated in serum.

- HBV and HIV Co-infection:

- The global HBV prevalence in HIV-infected persons is 7.4%. Conversely, about 1% of HBV-infected persons are also infected with HIV.

- The highest burden (71%) for HIV–HBV coinfection is found in sub-Saharan Africa

- Although HBV does not alter the progression of HIV, the presence of HIV greatly enhances the risk of developing HBV-associated cirrhosis and liver cancer.

- Tenofovir, a drug recently included in the treatment regimen of HIV is also active against HBV. This may have a role in controlling HIV-HBV coinfection.

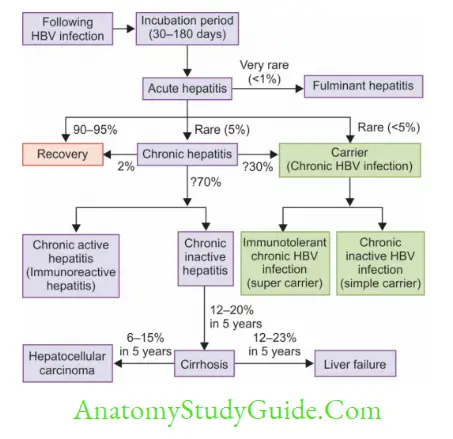

- Age: The outcome of HBV infection depends on the age. Following HBV infection:

- The chance of developing acute hepatitis is directly related to the age

- The chance of developing chronic hepatitis or carrier state is inversely related to age.

Laboratory Diagnosis of HBV

Definitive diagnosis of HBV depends on the serological demonstration of the viral markers. It does not grow in any conventional culture system.

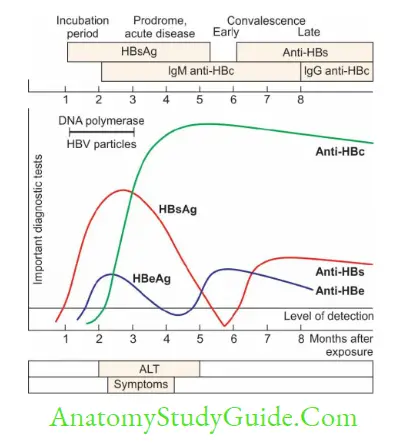

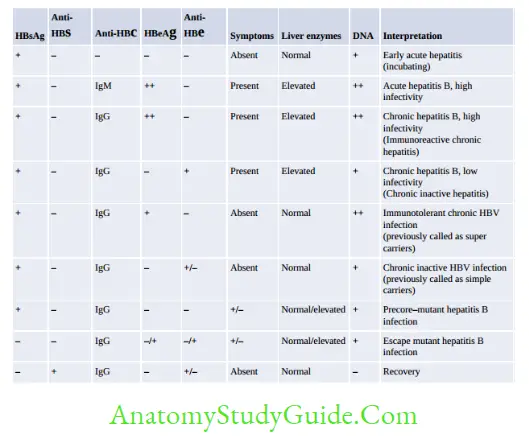

Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg)

HBsAg is the first marker to be elevated following infection; appears within 1–12 weeks:

- It appears during the incubation period; 2–6 weeks before the biochemical and clinical evidence of hepatitis

- The presence of HBsAg indicates the onset of infectivity

- It remains elevated for the entire duration of acute hepatitis;

- Becomes undetectable 1–2 months after the onset of jaundice and replaced by HBsAbindicate recovery

- Or, rarely persists beyond 6 months during chronic hepatitis and carrier state

- HBsAg is used as an epidemiological marker of hepatitis B infection (i.e. to calculate the prevalence of infection).

Hepatitis B Pre-core Antigen (HBeAg) and HBV DNA

They appear concurrently with or shortly after the appearance of HBsAg in serum

- They are the markers of

- Active viral replication

- High viral infectivity (i.e. they are highly infectious to others)

- However, they are present in either acute, chronic, or carrier state and it cannot differentiate between these stages.

Their presence just indicates that the virus is actively multiplying, which could be either-- Acute active hepatitis

- Chronic active hepatitis

- Or a carrier in whom HBV is actively multiplying and highly infectious (such carriers are called supercarriers).

Hepatitis B Core Antigen (HBcAg)

- HBcAg is a hidden antigen due to the surrounding HBsAg coat. It is also non-secretory; hence it cannot be detected in blood.

- However, HBcAg may be detected in hepatocytes by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Anti-HBc IgM (Hepatitis B Core Antibody)

- Anti-HBc IgM is the first antibody to elevate the following infection

- It appears within the first 1–2 weeks after the appearance of HBsAg and lasts for 3–6 months

- Its presence indicates acute hepatitis B infection

- It is probably the only marker (sometimes anti-HBc IgG) present during the period between the appearance of anti-HBs antibodies and the disappearance of HBsAg.

Anti-HBc IgG (Hepatitis B Core Antibody)

- Anti-HBc IgG appears in late acute stage and remains positive indefinitely whether the patient proceeds to:

- Chronic stage (with persistence of HBsAg, symptomatic and elevated liver enzymes)

- Carrier state (with the persistence of HBsAg but asymptomatic) or

- Recovery (appearance of Anti-HBs antibody).

- It can also be used as an epidemiological marker of HBV infection.

Anti-HBe (Hepatitis B Precore Antibody) - Anti-HBe antibodies appear after the clearance of HBeAg

- Its presence signifies diminished viral replication and decreased infectivity.

Anti-HBs (Hepatitis B Surface Antibody) - Appears after the clearance of HBsAg and remains elevated indefinitely

- Its presence indicates recovery, immunity, and non-infectivity (i.e. stoppage of transmission)

- It is also the only marker of vaccination.

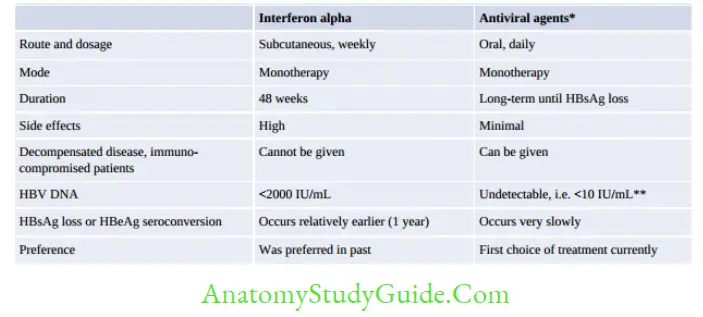

Treatment

Most acute hepatitis B infections are self-limiting, and do not require any specific treatment. With the advent of newer antiviral drugs, now it is possible to contain the disease.

Indications to Start Treatment

- Acute hepatitis with acute liver failure

- Chronic active hepatitis (immunoreactive hepatitis, HBeAg positive)

- Chronic inactive hepatitis (HBeAg –ve):

- HBV DNA >2,000 IU/mL plus ALT ↑ (> normal) plus moderate degree of liver fibrosis

- HBV DNA >20,000 IU/mL and ALT ↑ ↑ (>2 times normal); regardless of the degree of liver fibrosis.

- Associated cirrhosis (regardless of ALT level, viral load)

- Carriers (super or simple) with a family history of HCC or cirrhosis.

- Supercarriers or immunotolerant hepatitis (here, treatment is indicated if the person’s age is >30 years)

Antiviral Agents - Antiviral agents (nucleoside analogs): Tenofovir and telbivudine are the agents of choice currently. Lamivudine, adefovir, and entecavir can also be used, but they are less preferred because of the high risk of development of resistance.

- Pegylated interferon alpha (used previously; now not in use because of adverse effects).

Prophylaxis

Active Immunization (Hepatitis B Vaccine)

The Hepatitis B vaccine is a recombinant subunit vaccine.

- The surface antigen (HBsAg) is used as a vaccine candidate which is prepared in Baker’s yeast by DNA recombinant technology by cloning the S gene into the yeast chromosome.

- Route of administration: By IM route over the deltoid (in the infant-anterolateral thigh)

- Dosage: 10–20 µg/dose (half of the dose is given to children below 10 years)

- Schedule:

- Recommended schedule for adults: Three doses are given at 0, 1, and 6 months.

- Under the National immunization schedule: It is given at 6, 10, and 14 weeks (along with the DPT vaccine). Additional dose at birth may be given in areas with prevalence of HBV > 8%

- The minimum interval between the doses- 4 weeks.

- Marker of protection: Recipients are said to be protected if the anti-HBsAg antibody titer is > 10 IU/ml.

- However, nonresponders (do not show seroconversion after two series of vaccination; i.e. six doses of vaccination) and low responders (seroconversion occurs slowly after the second series of vaccination) may be seen in 5–10% of vaccinated individuals.

- Protection may last for a long time (decades)

- Booster doses are not needed, except for the transplant recipients who may need a booster if the antibody titer falls below 10 IU/ml.

Passive Immunization(Hepatitis B Immunoglobulin or HBIG)

Indications: Where immediate protection is warranted.- Acutely exposed to HBsAg-positive blood, e.g. surgeons, nurses, laboratory workers

- Sexual contact of acute hepatitis B patients

- Neonates borne to hepatitis B carrier mothers

- Post liver transplant patients who need protection against HBV infection.

- Following accidental exposure, HBIG should be started immediately (ideally within 6 hrs, but not later than 48 hrs).

- The recommended dose is 0.05–0.07ml/kg body weight, and two doses of HBIG should be given 30 days apart.

- HBIG gives short-term passive protection which lasts for about 100 days.

Combined Immunization

Combined immunization with HBIG + vaccine is recommended for neonates born to HBV-infected mothers, where a single injection of 0.5 ml of HBIG is given to the neonate immediately after the birth, followed by a full course of vaccine given at a different site (the first dose being given within 12 hours of birth). - The guideline for post-exposure prophylaxis is as follows:

- If the exposed person is vaccinated and the antibody titer is protective (i.e. >10 IU/ml) No further treatment is needed

- If the exposed person is vaccinated and the titer is not protective (i.e. < 10 IU/ml):

- HBIG: Should be started immediately

- Vaccine: A single dose should be given within 7 days of exposure.

- If the exposed person is not vaccinated: HBIG and a full course of vaccine (3 doses) are needed.

Hepatitis C Virus

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the common cause of post-transfusion hepatitis in developing countries.

- HCV is classified under the family Flaviviridae, genus Hepacivirus

- It is spherical, 60 nm size and enveloped virus, contains positive sense ssRNA.

- HCV possesses 3 structural proteins: The nucleocapsid core protein C; two envelope glycoproteins (E1 and E2) and Six nonstructural (NS) proteins: NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B.

Genetic Diversity of HCV

HCV displays diversity in the RNA genome due to high rates of mutations in the virus.

- Genotypes: HCV is divided into 6 genotypes or clades, which differ from each other by 31-33% in RNA sequence.

- Subtypes: Genotypes are further divided into 100 subtypes, which differ from each other by 15–25% in their RNA nucleotide sequence. In any given patient, the subtypes of

- HCV circulates as a complex closely related viral population known as quasispecies.

- E2 envelope protein is the most variable region of the HCV genome and hence more prone to undergo mutations, which results in: (1) Chronic infection, (2) Failure of vaccine HCV genotypes do not vary in clinical severity but they vary in their epidemiological

distribution: - Genotypes 1 and 2 represent the most common variants in Western countries

- Genotype 3 is widely distributed in South and East Asia with subtype 3a common among IV drug users from Europe

- In India, genotypes 1 and 3 are more prevalent.

- Genotypes also vary in their susceptibility to antiviral drugs. Patients with genotype-1b respond more poorly to therapy than other genotypes.

Transmission

HCV is transmitted by Parenteral (most common), Vertical-less risk (6%) than that of HBV (20%) and Sexual

HCV does not spread through breast milk, food, or casual contact (hugging or kissing).

Clinical Manifestations

The incubation period is about 15–160 days (average 50 days). Following an infection with HCV:

- About 20% of people develop acute hepatitis

- About 75–80% directly develop chronic disease; out of which:

- 60–70% develop chronic hepatitis

- 5–20% develop cirrhosis

- 1–5% develop hepatocellular carcinoma. (HCV accounts for 25% of total liver cancer patients).

Extrahepatic manifestations: Due to deposition of circulating immune complexes in various sites leading to manifestations such as (1) Mixed cryoglobulinemia (2) Glomerulonephritis (3) Arthritis and joint pain.

Laboratory Diagnosis

HCV Antibody Detection Assay (ELISA)

- First and second-generation ELISA: These were used previously. HCV antigens (core, NS3, and NS4) were used for the detection of antibodies.

- Third generation ELISA: Uses NS5 region in addition to core, NS3 and NS4 regions; It has advantages such as (i) increased sensitivity and specificity (>99%); (ii) not influenced by HCV genotype, (iii) becomes positive in 5 weeks of infection; However, these do not discriminate between active or past infection and can give false positive result (in autoimmune diseases, mononucleosis, and pregnancy) and false negative result (in immunosuppression).

Recombinant Immunoblot Antibody Assay (RIBA)

RIBA was used in the past as a supplementary test to confirm the ELISA result; not in use currently.

HCV Core Antigen Assay

- Automated quantitative tests detecting core antigens are less expensive and less time-consuming than HCV RNA PCR. An ELISA format has recently been available that detects simultaneously antigen (capsid Ag) and antibody (to NS3 and NS4 Ag).

- Advantages: can be used for (1) diagnosis of active/current infection, (2) monitoring response to treatment

- Disadvantage: They are less sensitive than RT-PCR; not used for blood screening.

Molecular Methods

Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR detecting HCV RNA has been the gold standard method for:

- Confirmation of active HCV infection.

- Quantification of HCV RNA for monitoring the response to treatment

- For determining HCV genotype and subtype.

Diagnosis of Acute HCV Infection

- Acute HCV infection (i.e. onset of symptoms within 6 months of exposure) occurs very rarely.

- Both IgM and IgG antibodies appear during the acute stage; IgM may persist during the chronic stage for a variable time; whereas IgG persists for a long duration both in the chronic stage and during recovery

- There is no IgM-based assay available currently

- The acute infection can be diagnosed by: (1) anti-HCV IgG seroconversion, (2) HCV RNA positivity, or (3) IgG avidity assay (low avidity indicates acute infection, strong avidity may indicate chronic/past infection).

Treatment

The goal of treatment for HCV infection is:

- To prevent the development of complications such as cirrhosis and liver cancer

- To achieve sustainable viral response (SVR) which is defined as undetectable HCV RNA in blood (≤15 IU/mL) at the end of treatment.

- Interferon alpha plus ribavirin: Earlier, pegylated-interferon (PEG-IFN) alpha plus ribavirin (RBV) was used previously, but had adverse effects; now not used.

- Direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs): DAAs are now the treatment of choice for HCV infection as they can produce an SVR rate of up to 90% with minimal side effects.

- Three classes of DAAs are available: NS3/4A (proteases) inhibitors, NS5B (polymerases) inhibitors and NS5A inhibitors

- Combination therapy: Currently, the treatment regimen for HCV includes combinations of different DAAs with or without PEG-IFN and ribavirin. Most DAAs are genotype-specific; except sofosbuvir/velpatasvir which are active against all genotypes. The duration of the treatment regimen is either 12 or 24 weeks; depending upon the HCV genotype and the presence or absence of liver cirrhosis.

Predictors of Treatment Response

- Genotypes: People with HCV genotype 1b show the worst prognosis among all genotypes

- Viral RNA load: The higher the viral load (> 800,000 IU/mL), the worse the prognosis

- Interleukin 28B is a strong inducer of interferon-α.

- The presence of a certain variation of IL28B called CC genotype produces a stronger IFN-α release.

- Caucasians and African Americans lack CC genotype, hence showing a poor treatment response than that of Asians.

- Metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, and obesity decrease the chance of responding to HCV therapy.

Hepatitis D Virus

Hepatitis D is a defective virus; that cannot replicate by itself; and depends on Hepatitis B for its survival.

The association of HDV with HBV is of two types: Co-infection and Super-infection.

- Morphology: Hepatitis D is taxonomically unclassified though resembles viroids. It is 35 nm in size, consisting of:

- Circular, negative-sense ssRNA

- The protein coat made up of a single protein called hepatitis D antigen (HDAg)

- Surrounded by envelope protein derived from HBsAg from hepatitis B; hence it is called a defective virus.

- Transmission: Parenteral route is the most common mode; followed by sexual and vertical routes.

- Treatment: Patients with HDV infection can be treated with IFN-α and Treatment for HBV should also be continued.

- Prevention: Vaccination for HBV can also prevent HDV infection.

Hepatitis E Virus

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) causes enterically transmitted hepatitis primarily occurring in young adults which occurs as epidemics in developing countries.

- Although HEV resembles caliciviruses, taxonomically it belongs to the genus, Hepevirus, under the family Hepeviridae.

- Genotypes: HEV has a single serotype; however, five genotypes exist in nature

- Only four genotypes have been detected in humans

- Genotypes 1 and 2 appear to be more virulent and found exclusively in humans

- Genotypes 3 and 4 are found both in humans and other mammals. They are more attenuated and account for subclinical infections.

- Fulminant hepatitis may occur rarely in 1–2% of cases; except for the pregnant women who are particularly at higher risk (20%) of developing fulminant hepatitis.

Epidemiology

- Transmission: It is feco-orally transmitted via sewage contamination of drinking water or food.

- There is no chronic infection or carrier state.

- Epidemics have been reported primarily from India, Asia, Africa, and Central America; in those geographic areas,

- HEV is the most common cause of acute hepatitis in this zone.

HEV is unique among the known hepatitis viruses, in which it has an animal reservoir. HEV genotypes 3 and 4, animal-to-human transmissions occur. - In India, HEV infection accounts for maximum (30–60%) cases of sporadic acute hepatitis and epidemic hepatitis.

The first major epidemic was from New Delhi (1995) where 30,000 people were affected due to sewage contamination of the city’s drinking water supply following a flood that occurred in the Yamuna river - Though it resembles to HAV, features that differentiate HEV from that of HAV are:

- The secondary attack rate (spread from patients to their contacts) is rare (1–2%) in HEV, compared to 10–20% in HAV.

- Age: Young adults (20–40 years of age) are commonly affected in HEV, compared to children in HAV.

Laboratory Diagnosis

- HEV RNA (by reverse transcriptase PCR) and HEV virions ( by electron microscopy) can be detected in stool and serum even before the onset of clinical illness

- Serum antibody detection:

- IgM anti-HEV appears in serum at the same time as the appearance of liver enzymes and indicates acute infection

- IgG anti-HEV replaces IgM in 2 to 4 weeks (once the symptoms resolve) and persists for years; indicating recovery or past infection.

Hepatitis G Virus

Hepatitis G virus (HGV, also referred to as GB virus C) was discovered in 1995.

- It is related to the Hepatitis C virus, and belongs to the family Flaviviridae, under the genus Pegivirus

- HGV is transmitted by contaminated blood or blood products, or via sexual contact

- It replicates in the bone marrow and spleen; however, it is not associated with any known human disease so far.

- HIV co-infection: HGV commonly co-infects people infected with HIV (prevalence 35%); but surprisingly this dual infection is protective against HIV and patients survive longer.

Leave a Reply