The Alimentary System And Abdomen

Anatomy

Table of Contents

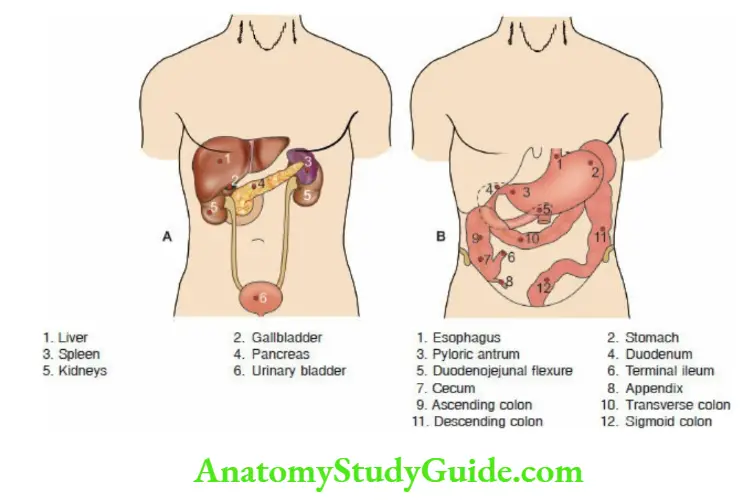

The gastrointestinal tract extends from the mouth to the anus.

It comprises a long and curled stretch of 8 meters of hollow tubes for passage and processing of food and includes the esophagus, stomach, pyloric antrum, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum (appendix at the ileocecal junction), ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and anal canal.

Read and Learn More Pediatric Clinical Methods Notes

It serves the purpose of swallowing and propulsion of food with peristalsis and is connected with an intricate network of nerves and secretory glands which secrete ptyalin, amylase, lipase, colipase, proteolytic enzymes which help in the process of digestion and assimilation of food which is absorbed and metabolized in the liver.

The partially digested and undigested food is propelled out as feces.

Apart from the gastrointestinal tract, the abdomen contains the liver with a gallbladder at its under surface in the right hypochondrium, a spleen in the left hypochondrium, a pancreas (with insulin-secreting islet cells) deep in the midline, two kidneys with adrenals one in each lumbar region with ureters which drain into the urinary bladder.

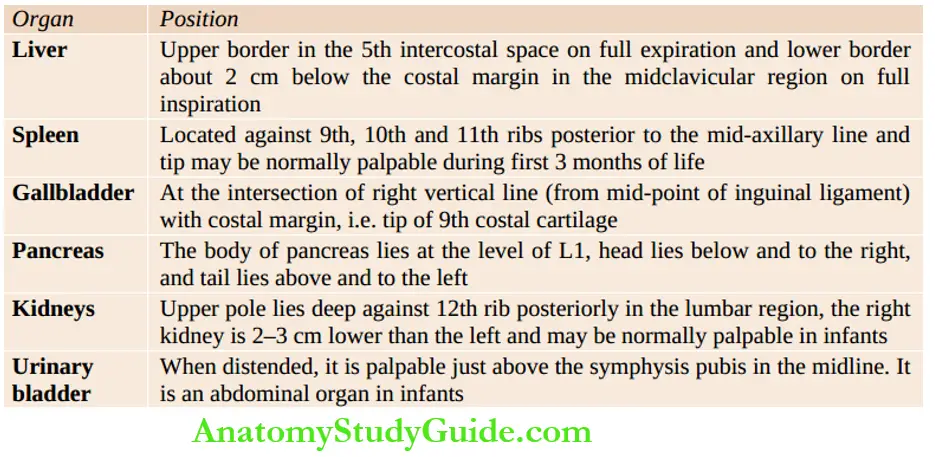

The surface markings and location of nonalignment viscera of the abdomen are shown. In females, the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries are located in the pelvis while in males testes in the scrotal sacs and penis hang from the pubis.

The left scrotal sac hangs slightly lower than the right. The peritoneum, a serous membrane, lines the abdominal cavity and provides a protective cover too many of the abdominal structures.

Double folds of peritoneum around the stomach constitute the greater and lesser omentum. The mesentery, a fan-shaped fold of the peritoneum, covers most of the small intestines and anchors it to the posterior abdominal wall.

History

Obtain a lucid account of the history of the present illness in chronological order without distorting the facts by asking too many direct or leading questions.

Special attention should be paid to the onset (acute, subacute, insidious) and evolution (progressive, resolving, static) of the disease process and response to therapy.

The common symptoms of gastrointestinal disorders include abdominal pain, bowel disturbances (diarrhea, constipation), vomiting, abdominal enlargement, jaundice, alteration in appetite (anorexia or excessive appetite), and failure to thrive.

Common symptoms of abdominal diseases

- Pain abdomen

- Dysphagia

- Dyspepsia, indigestion, heartburn, gastroesophageal ‘refluxâ€

- Constipation

- Diarrhea or malabsorption

- Anorexia or excessive appetite

- Flatulence and excessive wind

- Hiccups

- Nausea and vomiting

- Jaundice

- Abdominal distension

- Gl bleeding Hematemesis, rectal bleeding, and melena

- Dysuria or difficulty in passing urine, frequency of micturition, and red-colored urine

- Abdominal mass

- Weight loss or failure to thrive, malnutrition, and anemia

Fever may be a dominant feature in children with tuberculosis, malaria, kala-azar, viral hepatitis, cholangitis, amebic or pyogenic liver abscess, people, cholecystitis, leptospirosis, and malignant disorders.

Septicemia due to Gram-negative microorganisms is common in children with chronic hepatic dysfunction because of bypassing of the reticuloendothelial barrier of the liver by opening up portosystemic channels.

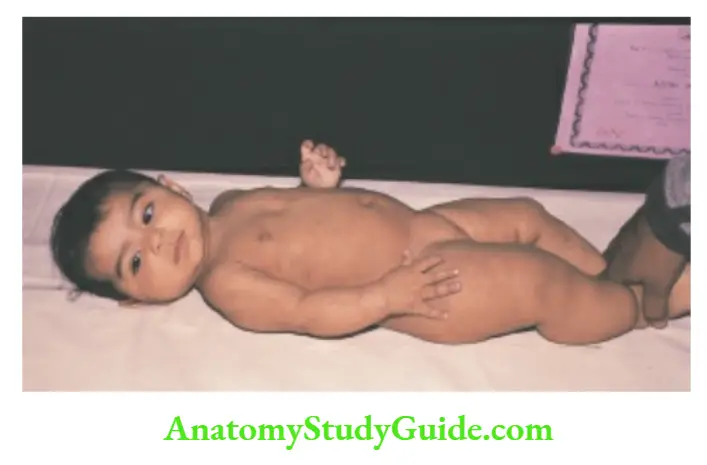

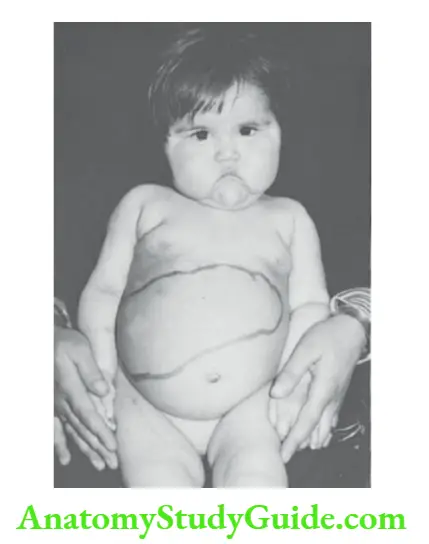

The potbelly contour of the abdomen is normal in infants and should not be considered evidence of liver disease.

The food fussiness and physiologic potbelly in preschool children are often attributed to liver dysfunction or “weak liver” by parents.

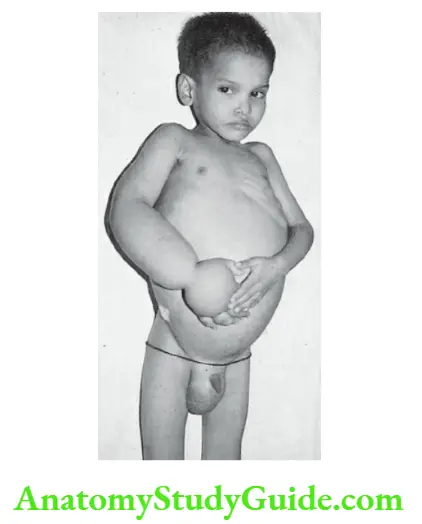

Progressive abdominal distension may occur due to enlargement of abdominal viscera, ascites, tumor, or gaseous distension.

Ask for a history of jaundice at the onset of the disease or in the past, whether jaundice is waxing and waning or is progressively increasing in severity.

A fluctuating pattern of jaundice is a characteristic feature of choledochal cysts, Dub in-Johnson syndrome, chronic active hepatitis, biliary calculi, and cholestasis.

Make sure that mother is not confusing pallor with jaundice by asking relevant questions. Information should be sought regarding the color of urine and stools.

The passage of persistently clay-colored or acholic stools and generalized itching is highly suggestive of obstructive jaundice.

History of intake of any hepato-toxic drugs or medicines from indigenous or alternative systems should be enquired.

The drugs which are known to be hepatotoxic include antitubercular agents, anticonvulsants, corticosteroids, androgens, sulfonamides, tetracyclines, macrolides, paracetamol, and nimesulide.

Ask for a history of transfusion of blood products as a source of transmission of hepatitis B or C virus.

When abdominal pain is a dominant symptom, ask specific questions to identify its site (whether pointed with a finger or vaguely referred to by the whole hand), severity (mild or severe enough to make the child cry), nature (constant, boring, colicky), radiation, relieving and aggravating factors.

Radiation of pain provides useful clinical guidelines. Renal colic typically starts in the loin and radiates to the groin and sometimes towards the genitalia and inner thigh.

Midnight pain, which awakens the child, is always pathological while morning pain may be a prank to miss the milk or school.

Acute appendicitis is characterized by a combination of symptoms and signs and should be ruled out.

Episodes of crying spells at night with arching of the back, vomiting, and poor feeding due to esophagitis are suggestive of gastroesophageal reflux disease.

A peptic ulcer is characterized by epigastric pain which is aggravated by the intake of NSAIDs, chilies, and caffeinated drinks, and relieved by the intake of food.

When a child complains of pain at multiple body sites, abdomen, chest, limbs, headache, etc. it is usually psychogenic or functional.

Forceful or persistent vomiting in association with failure to thrive and bile-stained vomitus are invariably pathological.

Ask about duration, severity, frequency, nature of vomitus, aggravating and relieving factors, and associated features.

Vomiting is a frequent complaint in viral hepatitis and liver dysfunction associated with the intake of hepatotoxins and inborn errors of metabolism.

Ask for a history of gastrointestinal bleeding (hematemesis, dysentery, and bleeding per rectum or hematochezia) and any generalized bleeding tendency. Painless bleeding without much fecal matter is suggestive of a rectal polyp.

Radiation of abdominal pain

- Pain due to renal and ureteric colic radiates downward towards the groin, inner side of thighs, and genitalia.

- Gallbladder pain usually radiates toward the tip of the right scapula.

- Pain due to diaphragmatic inflammation (cholecystitis, basal pneumonia) may radiate to the top of one or both shoulders.

- Pancreatic pain is excruciating boring in character and radiates towards the back.

Radiation of pain occurs due to identical innervation of the affected organ and the sites where the pain is radiated.

Characteristic clinical features of acute appendicitis

- The onset is with fever, vomiting, anorexia, and epigastric pain which shifts to the right iliac fossa.

- Guarding and tenderness over the right iliac fossa or McBumey’s point.

- Rebound tenderness may be present, i.e. pain occurs when the hand is released quickly after pressing the abdomen.

- Rovsing sign may be positive, i.e. pressure over the left iliac fossa is followed by pain in the right lower quadrant.

- The Psoas sign may be positive, i.e. there is slight flexion of the right hip due to irritation of the psoas muscle.

- Obturator sign may be positive, i.e. flexion and internal rotation of the right thigh causes abdominal pain.

- Ask the child to cough or jump. If there is no pain in coughing or jumping, acute appendicitis is unlikely.

The features may be atypical if the appendix is located at an ectopic site. Constipation is common but diarrhea may occur with retrocecal or pelvic appendix.

McBurney point is located in the right lower abdomen at the junction of the outer two-thirds and inner one-third of the line joining the anterior superior iliac spine with the umbilicus.

Most alimentary disorders are associated with anorexia.

Excessive or voracious appetite may be seen in children harboring ascaris, endocrinal disorders (hypothalamic dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism), recovering from hepatic dysfunction, or receiving corticosteroids.

Ask for discriminatory details regarding bowel disturbances. History was suggestive of steatorrhea and evidence of deficiency of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) should be sought.

Failure to thrive and developmental retardation may occur as a consequence of chronic liver dysfunction, intrauterine infections, and inborn errors of metabolism.

A family history of tuberculosis and a history of a liver disorder in other siblings should be enquired.

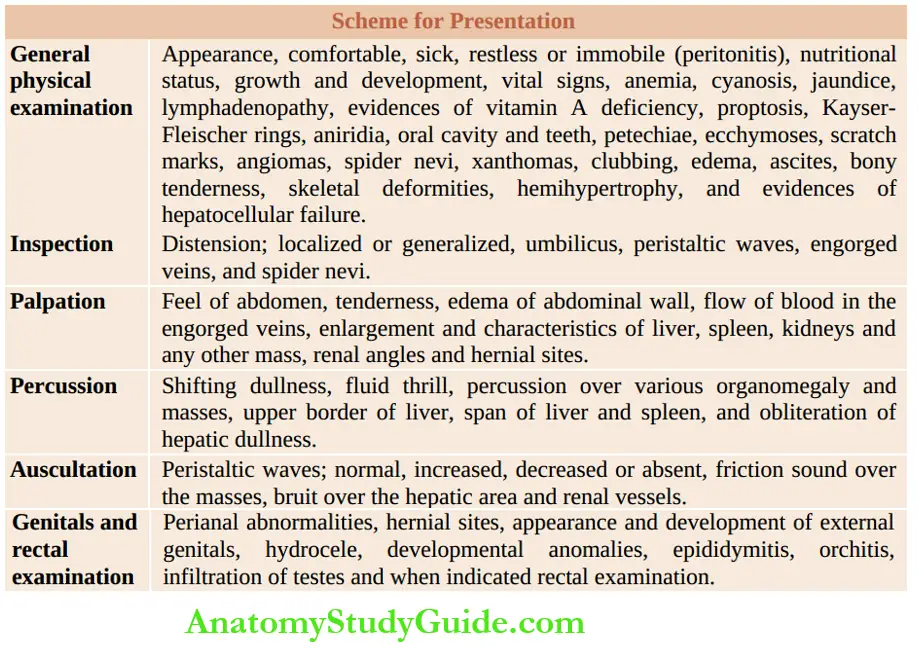

General Physical Examination

Attitude or decubitus of tire patients provides useful information. Children with peritonitis are motionless, while those with abdominal colic are restless.

Pinched facies with a sallow complexion are seen in cirrhosis. Dyspnea may occur due to massive ascites.

Eyes should be examined for proptosis (cholera, neuroblastoma), cataracts, Kayser-Fleischer ring, macular degeneration, chorioretinitis, and signs of deficiency of vitamin A.

Kayser-Fleischer rings are grayish-green or golden-brown colored rings located along tire upper and lower borders of the cornea due to the deposition of copper in patients with Wilson disease, familial cholestatic syndrome, and chronic active hepatitis.

The finding may be visible to tire naked eye or with the tire help of a magnifying glass or slit-lamp examination.

When Wilson’s disease is suspected, look for CNS manifestations, like intentional tremors, dysarthria, dystonia, behavior changes, and deterioration in school performance.

Aniridia or absence of iris is a recognized correlate of Wilms tumor, Rieger syndrome, and neoplasms of the adrenal cortex and liver.

Enlargement of one-half of tire body hemihypertrophy may be associated with Wilms tumor, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, neurofibromatosis, visceral hemangiomas, hepatocellular carcinoma, and adrenocortical carcinoma.

Record temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure. Look for anemia, cyanosis (portal azygos shunt), jaundice, and lymphadenopathy. Assessment of the degree of pallor poses practical difficulties in a jaundiced child.

The palpebral conjunctiva, dorsum of the tongue, nails, and skin of the palm are reliable sites for the clinical evaluation of anemia.

In children, clinical jaundice is observed when serum bilirubin approaches 2 mg/dl while in a newborn baby, clinical jaundice does not manifest unless serum bilirubin is at least 4 mg/dl or more.

Jaundice is evaluated by examining scleral conjunctiva, under the surface of the tongue, buccal mucosa, and skin in natural daylight. Muddy conjunctiva should not be mistaken for jaundice.

In newborn babies, jaundice is best looked for by blanching the skin of the face around the nasolabial folds, the root of the nose, and the cheeks.

Jaundice is a characteristic feature of hepatocellular dysfunction, biliary obstruction, or cholestasis.

Jaundice is minimal or absent in patients with Reye syndrome and space-occupying lesions of the liver due to amebic and pyogenic liver abscess, hydatid cyst, and primary benign or malignant neoplasms of the liver.

Nutritional status It should be assessed by taking standard anthropometric measurements and by looking for evidence of protein-energy malnutrition and deficiencies of various micronutrients.

A large number of gastrointestinal disorders are associated with nutritional disorders, chronic diarrhea, malabsorption syndrome, celiac disease, mucoviscidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and giardiasis.

Growth and neuromotor development are retarded in children with inborn errors of metabolism, intrauterine infections, and chrome liver dysfunction.

The oral cavity is the tire portal of entry or window to the tire gastrointestinal tract and is likely to mirror and exhibit the inflammatory changes that take place in the tire gut.

Look for thrush (Mondial stomatitis), oral ulcers, membranous pharyngitis (streptococcal pharyngitis, diphtheria, infectious mononucleosis), herpangina, hypertrophied gums and macroglossia (glycogen storage disease, mucopolysaccharidosis, cretinism, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, gangliosidosis and new growth of tongue).

Recurrent episodes of oropharyngeal candidiasis are suggestive of a cell-mediated immunodeficiency state including AIDS.

Aphthous ulcers (acute herpetic gingivostomatitis) are small superficial painful ulcers with a white or yellow base with an erythematous halo of hyperemia.

They are distributed over tire gums, buccal mucosa, tongue, and palate and cause difficulty in feeding.

Stippled blue line over the tire edge of gums is suggestive of exposure to lead and may be associated with episodes of colicky abdominal pain, constipation, and basophilic stippling.

Diffuse hypertrophy of gums is common following phenytoin therapy, histiocytosis X, xanthomatosis, acute monocytic leukemia, and Hurler syndrome while epulis is a localized swelling of gums due to trauma, granuloma, or benign hyperplasia.

Pigmentation of lips and buccal mucosa is a recognized feature of Peutz-Jeghers polyps of the stomach or colon.

A bald and smooth tongue due to atrophy of papillae is suggestive of vitamin B12 deficiency, iron deficiency anemia, pellagra, and celiac disease.

“Strawberry tongue” is seen in patients with scarlet fever, bacterial toxic-shock syndrome, and Kawasaki disease due to the presence of white or bright-red enlarged papillae jutting against the bright-red surface of the tongue.

Congenital Assuring of the tongue or “scrotal tongue” is a common correlate of Down syndrome.

The geographical tongue is characterized by constantly evolving and changing irregular red areas of desquamated epithelium and filiform papillae with a sharp whitish-yellow border giving an appearance of a map over the tongue.

It is benign and of no pathological significance. Tongue-tie (ankyloglossia) is characterized by a short, thick, and fibrous frenulum, the inability to protrude the tongue, and a midline notch at tire tip of the tire tongue.

Examine the floor of the mouth for any cysts. Ranula is seen as a bluish-white translucent swelling due to the formation of a mucocele because of a ruptured salivary gland duct.

A sublingual dermoid cyst, on the other hand, is an opaque submucosal swelling due to the sequestration of epidermal tissue.

Skin and its appendages Skin should be examined for any petechiae, ecchymoses, scratch marks, angiomas, xanthomas, exanthem, seborrheic dermatitis, and photosensitivity.

Xanthomata over the extensor surfaces of extremities with xanthelasma in tire eyelids may be seen in children with prolonged cholestatic jaundice due to biliary obstruction.

Examine nails for clubbing (cirrhosis, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, malabsorption syndrome, polyposis of colon) and, leuconychia or white lines in tire nails (severe hypoalbuminemia due to nephrotic syndrome, Kwashiorkor, malabsorption due to celiac disease and protein-losing enteropathy).

Pedal edema, puffiness, ascites, and anasarca cair occur because of hepatic and renal disorders and malabsorption.

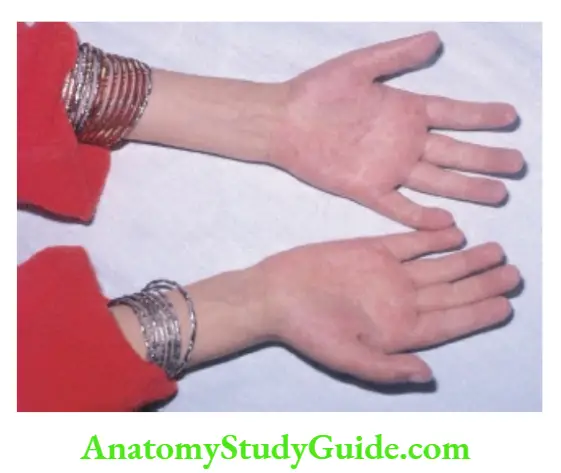

Evidence of hepatocellular failure Jaundice, alterations in sensorium (behavior changes, irritability, sleep disturbances, drowsiness), fetor hepatitis (musty odor of breath due to mercaptans), “flapping tremors”, palmar erythema, hyperreflexia, extensor planters, and spider nevi should be looked for.

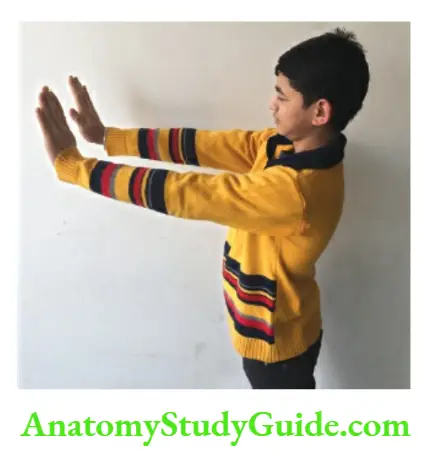

“Liver flap” or asterixis is demonstrated by asking the patient to extend both arms and try to maintain hands in a dorsiflexed position.

There will be nonrhythmic asymmetric flaps or drops of hands due to the inability to maintain the position of liver dysfunction because of the accumulation of female sex hormones due to their reduced breakdown in the tire liver.

In adolescent girls with chronic active hepatitis, there may be delayed puberty, menstrual irregularities, amenorrhea, and acne.

Bony swellings and tenderness are important signs of infiltrative disorders of bones, especially acute leukemia.

Skeletal deformities (mucopolysaccharidosis), evidence of osteochondritis (congenital infections especially syphilis), rickets (cystinosis and tyrosinosis), and pathological fractures (Gaucher’s disease) should be looked for.

Tumors of soft tissue and bones especially involving the mandible may be associated with familial intestinal polyps (Gardner syndrome).

The spine should be examined for Pott’s disease. Psoas sign appears due to inflammation of the psoas muscle due to appendicitis, iliac adenitis, and perinephric abscess.

It is characterized by slight flexion of the thigh, limp, and pain on sudden extension of the hip joint. Flexion and internal rotation of the thigh may cause abdominal pain (Obturator sign).

Examination Of Abdomen

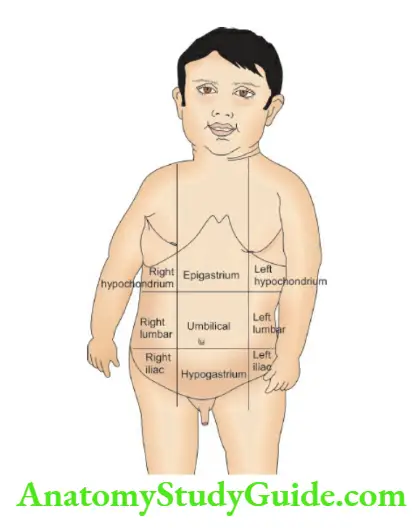

Clinical quadrants For clinical purposes abdomen is divided into 9 quadrants, right hypochondrium, epigastrium, left hypochondrium, right lumbar (flank), umbilical, left lumbar (flank), right iliac fossa, hypogastrium or suprapubic region and left iliac fossa

Inspection

Note the contour of the abdomen, whether normal, bloated or bulging, and depressed or concave. Look for any scar over the abdominal wall and ask for the nature of the surgical procedure done.

Movements of all quadrants, fullness whether localized or generalized, position and shape of the umbilicus (flushed or everted), discharge, inflammation, and nodule should be looked for.

In ascites, there is an enlargement of the abdomen with the fullness of flanks and the umbilicus appears as a transverse slit.

There may be umbilical granuloma or bright-red polyp in a newborn baby. Polyp may have a small opening discharging urine (persistent urachus or urachal cyst) or serosanguinous fluid or fecal matter through the omphalomesenteric duct.

Periumbilical ecchymosis (Cullen sign) and ecchymoses of one or both flanks (Grey-Turner sign) are suggestive of intraabdominal hemorrhage due to pancreatitis and rupture of the liver or spleen.

Look for any visible and engorged veins and assess the direction of the flow of blood. The direction of flow of blood may be determined by placing both tire index fingers at a point over the branchless segment of the engorged vein.

The vein is emptied by stripping one of tire index fingers over it. One index finger at a time is taken off the tire vein to ascertain the direction of the flow of blood.

The normal flow of blood is away from the tire umbilicus thus draining tire blood from the tire umbilical veins into the tire portal system, hr portal hypertension, there are periumbilical engorged veins with the exaggerated flow of blood away from the umbilicus (caput medusae), hr inferior vena cava obstruction, tire engorged veins are at tire flanks with the flow of blood from below upwards while hr superior vena cava obstruction, the engorged veins are above the umbilicus with the flow of blood from above downwards.

Apart from engorged veins, there may be edema of the legs, buttocks and groins hr children with inferior vena cava obstruction.

Atrophic white or pink wrinkled striae may appear on tire abdominal wall and buttocks due to rupture of elastic fibers because of sudden distension (due to ascites and obesity) and stretching of the skin.

Broad purple striae are characteristic of Cushing syndrome and prolonged steroid therapy. Generalized distension and enlargement of the tire abdomen may occur due to fluid, gas, feces, fat, or a mass.

The abdomen is flat or scaphoid hr an infant with a diaphragmatic hernia, hr obstructive uropathy, there is a complete absence of muscles in the abdominal wall giving a wrinkled appearance to the abdomen (prune-belly syndrome).

Localized distension may occur around the tire umbilicus (small bowel obstruction, mesenteric cyst), hypochondriac regions (liver, spleen), or above tire symphysis pubis (urinary bladder, uterus, or ovary).

The site and direction of peristaltic waves should be looked for. Gastric peristaltic waves, passing across tire upper abdomen from left to right, are classically seen in infants with pyloric stenosis.

Distended coils of the small bowel may be seen in the tire center of the abdomen or a “ladder pattern” hr children with subacute obstruction of the small bowel.

Palpation

The hands should be warm and nails should be trimmed for satisfactory abdominal examination. Divert the child’s attention by conversation during palpation.

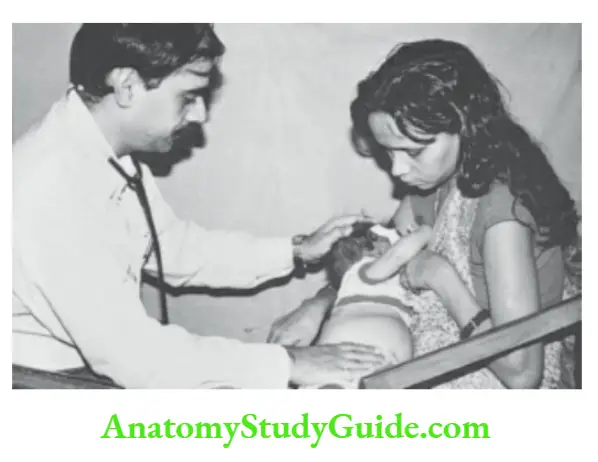

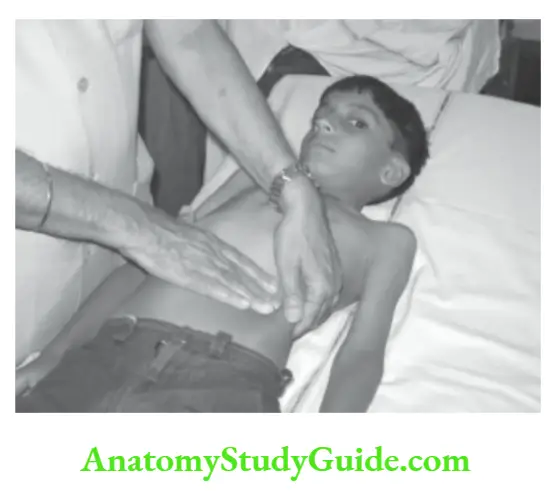

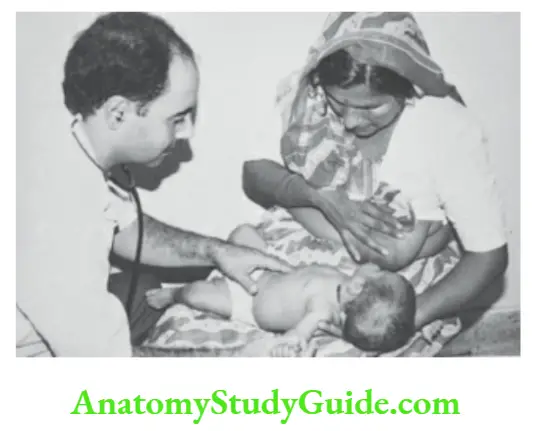

Infants are generally apprehensive and often cry and straight thus tensing tire abdomen. It is best to examine an infant’s mother’s lap.

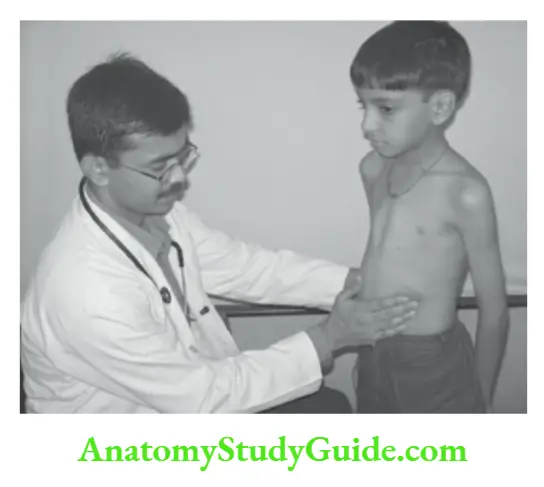

Breastfeeding is tiring best soother to elicit cooperation. Preschool children are best examined in a standing position. Older children can be asked to lie on the examination table, flex their hips, relax, and take deep breaths.

Palpate the abdomen with the flat of the hand with slight flexion of metacarpophalangeal joints rather than the tips of fingers.

The site of the abdomen where the child localizes pain should be examined in the end after having palpated other areas of the abdomen.

During palpation, watch the child for any change in facial expression, wincing, or screwing of eyes or forehead as evidence of tenderness.

It is unnecessary and unreliable to ask the child whether it hurts or not.

“Dipping technique” is used, if massive ascites are present. The viscera are explored by sudden but gentle dipping of fingers.

At times satisfactory abdominal examination is possible only after paracentesis. The feel of the abdomen may be normal, soft, doughy, tense, and rigid.

Tenderness may be localized, generalized and gurgling sounds may be palpable.

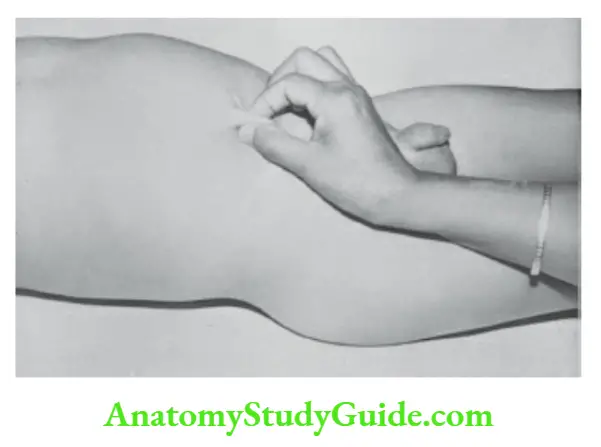

Edema of the abdominal wall is assessed by pinching the skin for 5 seconds or by seeing the impression created by the diaphragm of the stethoscope following auscultation.

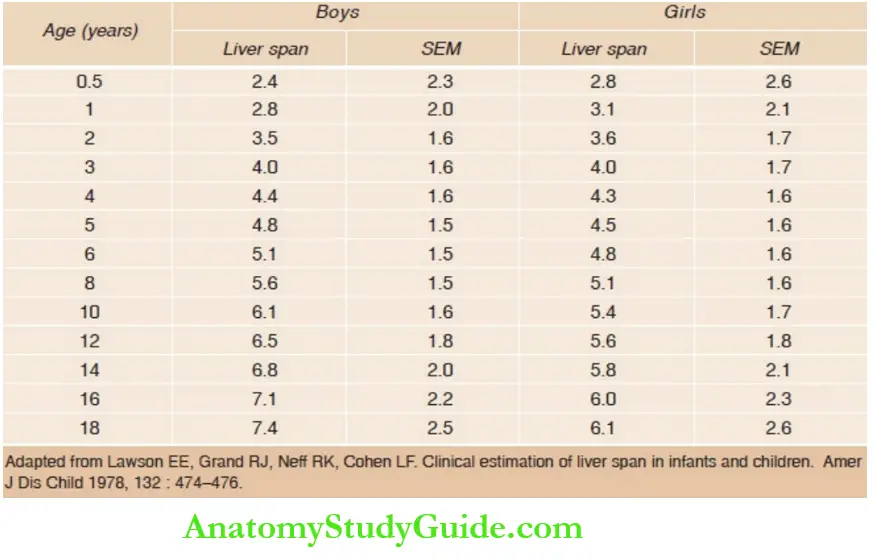

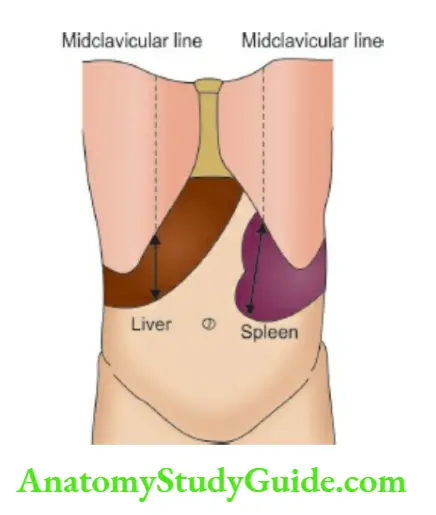

Look for enlargement of the liver (don’t forget to identify the upper border and span of the liver), spleen, kidneys, cecum, and descending colon. The expected liver span in normal children between 6 months and 18 years is given in.

The liver is normally palpable up to 2 cm below the costal margin throughout childhood while the spleen tip may be palpable in infants during the first 3 months of age.

The normal liver is soft and has a rounded margin. Ascertain the consistency of the liver and whether the surface is smooth, granular, or nodular.

When the margin of the liver is sharp and well-defined, it is suggestive of the firm or hard consistency of the organ. The liver may be pulsatile in children with tricuspid regurgitation.

The presence of pitting edema or tenderness over the intercostal spaces overlying the hepatic region supports the possibility of underlying amebic or pyogenic abscess.

Asymmetric or focal enlargement of the liver with the elevated upper level of hepatic dullness is seen in children with amebic or pyogenic liver abscess, hydatid cyst, focal nodular hyperplasia, benign neoplasms, and primary or metastatic malignancy.

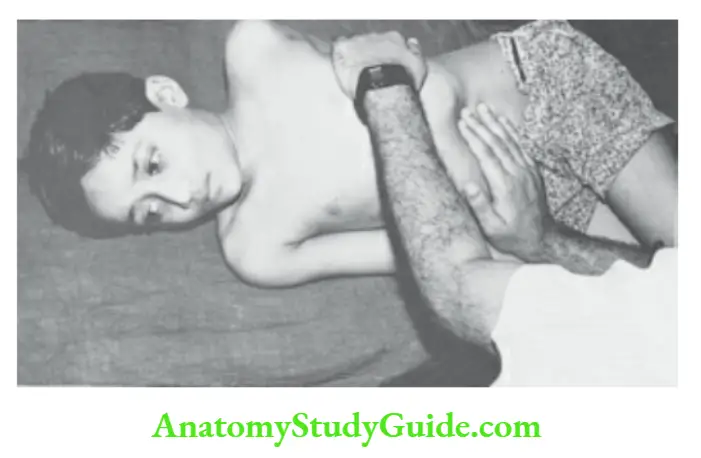

Turn the child to the right lateral position to feel the tip of just palpable spleen. The spleen becomes palpable when it enlarges to at least two to three times its size. The spleen enlarges downward and medially towards the right iliac fossa.

Key points for examination of liver and spleen

- Enlargement beyond the costal margin (cm)

- Edge: Round, sharp, well-defined or ill-defined, notch present or not

- Consistency: Soft, firm, or hard

- Surface: Smooth, granular, nodular, lobular

- Tenderness: Present or absent

- Upper border or level of the dullness of liver and spleen (intercostal space)

- The span of the liver and spleen by measuring from the upper border to the palpable margin (cm)

The enlargement of the liver and spleen is measured from the midclavicular point over the costal margin to the lowermost edge of the organ.

The liver and spleen may become palpable due to downward displacement (without enlargement) because of contractual deformities of the thorax, hyperinflated lungs, basal pleural effusion, increased intrathoracic pressure, subphrenic abscess, or collection of air and relaxation of abdominal musculature because of gross hypotonia.

Kidneys should be palpated by the bimanual technique. The lower pole of the right kidney may be normally palpable in some children. Renal angles, their fullness, tenderness, and pitting edema should be looked for.

Look for any mass and assess whether it is intra-abdominal or in the wall of the abdomen by the Rising test.

When a patient is asked to sit up from a supine position, the intra-abdominal mass becomes less prominent and difficult to palpate while the parietal mass becomes small and immobile.

Divarication of the recti is noted as a linear bulge between the recti muscles when a supine child is asked to sit up.

Identify the site, size, shape, and mobility of the mass with respiration and from side to side, bimanual palpability, does it cross the midline, and whether it is pulsatile or not.

Try to assess whether the upper and lower borders of the mass are distinctly felt or are “lost” into the thorax (liver and spleen) or pelvis (bladder, uterus, and ovary).

The main purpose of the clinical examination of an abdominal mass is to assess the organ of origin and the pathological nature of the mass.

The consistency, margins, tenderness, and percussion characteristics of the mass should be ascertained.

The salient points for examining an abdominal mass are listed. A special technique is used for the palpation of pyloric tumors.

While the infant is being fed on the left breast, the pylorus is explored with the fingers of the left hand by palpating gently but deeply lateral to the edge of the right rectus muscle in the epigastric region.

Pyloric mass, an olivelike firm swelling is located at a point 2 to 3 cm above and to the right of the umbilicus. A mass of retroperitoneal origin is fixed while a mesenteric cyst or mass can be made to move freely from side to side.

The urinary bladder is an intra-abdominal organ in children and is easily palpable when full. Midline globular cystic mass over the suprapubic region is usually due to a distended bladder.

The swelling disappears on the evacuation of urine.

The common causes of the distended bladder include a postoperative state, posterior urethral valve, urethral stone, encephalopathy, neurogenic bladder due to meningomyelocele, paralytic poliomyelitis, transverse myelitis, and Gullain-Barre syndrome.

In children with constipation, hard fecal masses (which can be indented on pressure) are felt over the descending colon region in the left iliac fossa.

Salient points for examining an abdominal mass

- Is it parietal (located in the wall of the abdomen) or intra-abdominal?

- Location of the mass and its likely visceral origin

- Size and whether it crosses the midline or not

- Whether upper and lower borders of the mass can be reached?

- Cystic or solid

- Consistency: Soft, firm, or hard

- Surface: Smooth, granular, nodular, lobular

- Is mass pulsatile? Are pulsations transmitted or true expansile pulsations?

- Is the mass tender or painless?

- Mobility on breathing and side-to-side mobility of the mass

- Ballotable and bimanu palpable or not

- Percussion: Tympanitic, resonant, dull, with or without hydatid thrill

- Auscultation: Bruit or friction rub

The hernial sites should be examined for umbilical and inguinal hernias. Transillumination of swelling whether parietal or intra-abdominal, is useful to differentiate between a cystic and a solid mass.

Examine external genitals for any abnormality.

Percussion

The abdomen is tympanic on percussion and it becomes excessively tympanic or “resounding” in a child with intestinal obstruction or paralytic ileus.

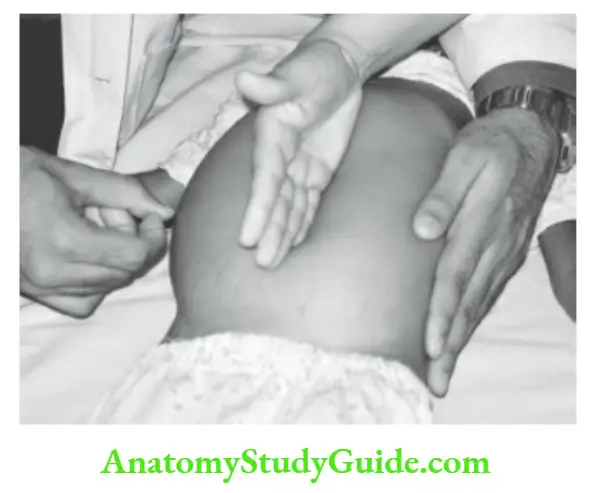

Look for shifting dullness, fluid thrill, puddle signs, and percussion over the mass. For eliciting shifting dullness, the patient is placed in a supine position.

Percussion is performed from the umbilicus towards one of the flanks (avoid the flank which is occupied by an enlarged viscus or mass) till dullness is elicited.

The child is turned to the other side and held in a lateral position to allow the fluid to gravitate toward the umbilicus.

In this position, the non-dependent flank will become resonant while percussion would be dull over the umbilicus and dependent flank when there is free fluid in the abdomen.

A fluid wave or thrill appears later and is eligible when ascites become moderate or massive.

One hand is placed over the flank and sharp taps are given over the other flank with the index finger of the dominant hand of the examiner. Distinct thrill due to movements of ascitic fluid shall be appreciated.

To prevent transmission of tapping impulse traveling through the abdominal wall, the assistant or patient is asked to firmly place the hypothenar edge of his outstretched hand over the midline of the abdomen.

Massive ascites with non-pitting unilateral lymphedema of a limb are suggestive of chylous ascites.

For the diagnosis of minimal ascites, the child is placed in a knee-elbow position to ensure the gravitation of fluid to the mid-abdominal region.

The chest piece of the stethoscope is placed over the mid-abdomen and the abdominal wall is gently tapped with the index finger moving from one flank towards the center till a water puddle sound is audible when the edge of the ascitic fluid pocket is tapped (Puddle sign).

Liver dullness, which is normally present between the 6th rib and costal margin may be obliterated, if there is free gas in the peritoneal cavity.

Splenic dullness extends from the 9th to the 11th ribs on the left side.

Hydatid thrill should be looked for whenever there is gross isolated hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. The displaced scolices and hydatid “sand” touch the pleximeter finger soon after the tap.

Auscultation

Peristaltic sounds may be normal, decreased, absent, or exaggerated (borborygmi). Exaggerated intestinal sounds are heard in children with intestinal obstruction and during intestinal colic.

In generalized peritonitis and a state of paralytic ileus, the abdomen becomes silent.

Friction sound over the enlarged liver and spleen is suggestive of perihepatitis and peri splenitis (sickle cell anemia, abscess, leukemic infiltrates).

Bruit over the hepatic area suggests the possibility of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia or hemangioendothelioma.

Venous hum may be audible over the epigastric region in children in whom extensive portosystemic collateral circulation is established.

Bruit over the lumbar areas anteriority on either side of the midline should be looked for in children with hypertension.

The abdomen should be firmly pressed backward with the chest piece of the stethoscope to identify the bruit due to renal artery stenosis.

Succussion splash may be elicited by auscultating the stomach area while gently shaking the patient.

A splashing sound like the noise made by a hot water bottle partially filled with water and air is heard when the stomach is distended with fluid.

Genitals And Groin

Inguinal nodes are located in two chains, the horizontal drain below the tire inguinal ligament and a vertical chain along the tire line of the saphenous vein.

Look for enlarged lymph nodes in the tire inguinal region which are common and of no significance in children who walk bare feet. Inguinal lymph nodes may enlarge in association with generalized lymphadenopathy.

Enlarged and exquisitely tender inguinal lymph nodes are seen in patients with bubonic plague due to Yersinia pestis. Look for any inguinoscrotal swelling due to hernia or hydrocele.

In a hernia, the upper border of the swelling cannot be reached, swelling increases in size and has an expansile impulse on crying or coughing and may reduce in size or disappear on lying down.

Hernia is reducible by manipulation and opaque on transillumination, unlike hydrocele. Physiologic hydrocele may be present at birth and it usually disappears by 3 months of age.

When inguinoscrotal swelling is not reducible, it is suggestive of hydrocele of the spermatic cord or an incarcerated inguinal hernia.

Male genitalia Look for tight prepuce or phimosis and balanitis or mastitis and posthitis (inflammation of prepuce) which are important correlates of urinary tract infection.

The foreskin is not retractable in children below 2 years of age but it causes no difficulty in voiding. Transient small epithelial pearls or inclusion cysts may be present on the distal portion of the prepuce in newborn babies.

In adolescent boys, pearly white papules 1–3 mm in size may be seen on the penile corona and should not be confused with venereal warts. Look for the urethral opening which is normally located on the tip of the glans.

hi epispadias, the urethral opening is located on the dorsal surface of the penis while in hypospadias urethral meatus opens on the ventral surface of the penis.

The opening may be located anywhere on the ventral surface of the glans, the shaft of the penis, the penoscrotal region, and the perineum. When hypospadias is associated with ventral curvature of the penis, it is called chordee.

Look for cryptorchidism or ectopic testis and ambiguous genitals which may be missed by parents. The retractile testis can be pulled down gently into the scrotum and should not be confused with the undescended testis.

Micropenis is rare and diagnosed when the penile length is less than 2.0 cm in infants. It should not be confused with embedded penis in obese children.

Enlargement of the testis, with or without pain, may occur due to orchitis (mumps, coxsackie, rubella), epididymitis, leukemic infiltrates, Henoch-SchÏŒnlein purpura, torsion of the appendix of testis and tumor.

Torsion of the testis is characterized by sudden onset of severe pain, swelling of the testis, tenderness, scrotal edema with a “blue dot” discoloration, and absence of cremasteric reflex.

The varicoceles due to varicosities of spermatic veins feel like a “bag of worms” in the scrotum. Swelling at the upper pole of the testis may occur due to epididymitis or spermatocele (painless).

Assess the sexual maturity rate and stage, hi precocious puberty, both testes and penis are large in size while in congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), there is an isolated enlargement of the phallus.

Female genitalia The adolescent girl must be examined in the presence of a nurse or female attendant. Look for any vaginal discharge, redness, foreign body, and hematocolpos due to an imperforate vagina.

Vulvovaginitis may occur due to bacterial vaginosis, pinworm infestation, trichinosis, Chlamydia trachomatis, Candida infection, herpes simplex, and trauma or sexual abuse.

Look for ambiguous genitalia and clitoral enlargement or virilization, which is a characteristic feature of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH).

Clitoris has two paramedian frenulae (unlike the penis which has a single frenulum) on its ventral surface and is covered with tissue on its superior aspect.

Sarcoma botryoid is characterized by a moist grape-like fleshy mass jutting out of the vulva. The sexual maturity rating should be assessed.

Rectal Examination

Look for perianal excoriations, mucocutaneous lesions, skin tags, inflammation, and nappy rash. Anal skin tags are common and are of no significance.

The prolapse of a rectal polyp appears as a dark beefy-red mass as compared to the lighter pink mucosal appearance of rectal prolapse.

The common causes of rectal prolapse in children include malnutrition, acute or persistent diarrhea, chronic constipation, intestinal parasites especially trichinosis, ulcerative colitis, cystic fibrosis, celiac disease, pertussis, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. When there are rectal polyps, look for pigmentation of the oral mucosa (Peutz-Jeghers syndrome).

An anal fissure may occur due to severe constipation and is usually located at the 6 o’clock position and is associated with a tear in the lining of the anal canal.

The digital examination is likely to be extremely painful and should not be attempted on such a patient.

Rectal examination is indicated in children suspected to have an intestinal obstruction (Hrischsprung’s disease, intussusception), mass extending into the pelvis, rectal bleeding, and urethral stone.

The child is made to lie in the left lateral position and the right thigh and right knee are flexed. The examination is conducted by using the smallest finger depending upon the age of the child.

A well-lubricated little finger is used in newborn babies and infants, and an index finger in an older child. The child should be asked to relax and take deep breaths.

On withdrawing the finger after rectal examination, look at it for any staining with mucus, pus, and blood.

In Hirschsprung’s disease, the anal sphincter grips the finger and it is not possible to reach feces due to the presence of a narrow segment.

But when the finger is withdrawn, there is the explosive passage of flatus and feces located in the distended rectum. In functional megacolon, the anal canal is normal and the finger enters the mass of feces.

In anorectal stenosis, a ring or diaphragm is felt about 1.5–2.0 cm above the anal verge. In meningomyelocele and spinal cord injury, the anal sphincter may be lax and patulous.

Hi, distal or long-standing intussusception, a smooth rounded mass akin to the uterine cervix may be palpable with staining of the examiner’s finger with blood.

Clinical Characteristics Of Common Organomegalies

Liver

The liver is normally palpable up to 2 cm below the right costal margin throughout childhood. It is normally soft in consistency and has a rounded margin.

The pathological enlargement may occur upwards though it is generally downwards towards the right hypochondrium and umbilical regions.

The margin is well-defined and it moves freely with respiration. The fingers cannot be insinuated between the liver and the costal margin. It is not bimanual palpable and is not mobile from side to side.

The enlargement may affect any lobe of the liver but generally both the lobes are simultaneously enlarged. The left lobe of the liver may be more prominent in children with amebic abscesses and portal hypertension.

It is dull on percussion and dullness merges with subcostal hepatic dullness. The upper border of hepatic dullness must be identified on percussion to calculate liver span.

Auscultate the liver to look for hepatic rub due to perihepatitis, liver abscess, and leukemic infiltrates.

Significantly isolated hepatomegaly with minimal or absence of splenomegaly is seen in children with cardiac failure, constrictive pericarditis, liver abscess, hydatid cyst, glycogen storage disease, cirrhosis, primary or metastatic malignancy, mucopolysaccharidosis, veno-occlusive disease, Budd-Chiari syndrome, persistent hepatitis, and tuberculosis.

Gallbladder

The enlargement of the gallbladder presents as a pear-shaped swelling that projects beneath the center of the undersurface of the liver.

It is cystic in consistency and freely mobile from the side-to-side. Murphy’s sign may be positive in patients with acute cholecystitis.

Maintain constant but gentle pressure over the gallbladder region and ask the patient to take a deep breath. The patient “catches his breath” due to pain when the gallbladder touches the fingers.

Choledochal cyst produces a cystic swelling at a site identical to the gallbladder but swelling appears rather early in life and is fixed and non-mobile.

Spleen

The spleen has to enlarge by about two to three times before it becomes palpable. It enlarges downwards and medially towards the umbilicus. It moves freely with respiration.

The margin is characterized by a notch. The finger cannot be insinuated between the spleen and the costal margin. Anteriorly it is dull on percussion while posteriorly it is resonant.

It is not palpable manually. Auscultation may reveal scenic rub in a child with peri splenitis due to sickle cell disease.

Massive splenomegaly with minimal hepatomegaly is seen in children with portal hypertension, thalassemia major, chronic myeloid leukemia, myeloid metaplasia, chronic malaria, kala-azar, Gaucher’s disease, and amyloidosis.

Kidneys

Either one or both of the kidneys may be enlarged. The bean-shaped mass with rounded margins is located in the lumbar region. It does not move freely with respiration.

It is located more posteriorly causing bulging of the renal angle. It is manually palpable and mobile from side to side.

The kidney mass is resonant on percussion anteriorly but dull posteriorly. It does not cross the midline except when there is a horseshoe kidney.

Leave a Reply