The Respiratory System

Anatomy

Table of Contents

The respiratory system consists of the upper airway (up to the larynx) and the lower respiratory tract (trachea to alveoli).

The upper airway starts from the nose and mouth and includes the nasopharynx, sinuses, and larynx. The lower respiratory tract includes the trachea which bifurcates to provide bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli to two lungs.

Read and Learn More Pediatric Clinical Methods Notes

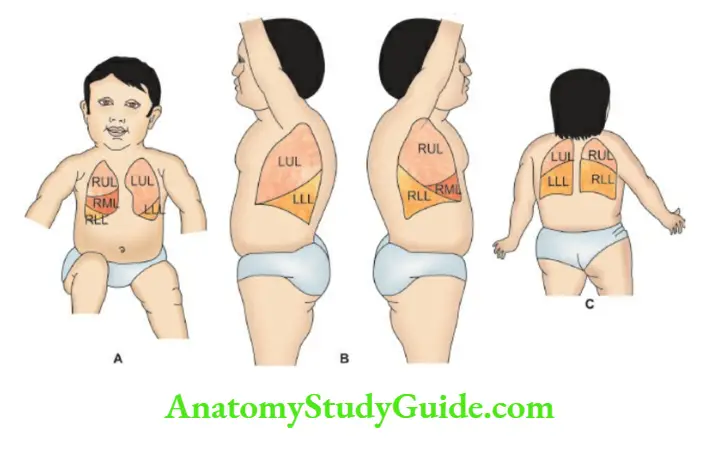

The right lung is bigger in size and has three lobes while the left lung is smaller in size due to the presence of a heart in the left hemithorax and has two lobes.

The air passages are relatively narrow in children which predisposes them to frequent development of stridor, wheezing, and atelectasis.

The chest is relatively round with a larger anterior-posterior diameter and the chest wall is thinner in children.

The airways transport air along with oxygen to the alveoli during inspiration and eliminate carbon dioxide during expiration.

The gas exchange takes place in the alveolar unit which consists of branching respiratory bronchioles with a cluster of alveoli.

Alveoli are tiny air sacs lined by flattened epithelial cells (type 1 pneumocyte) and are covered by a network of capillaries where gas exchange occurs.

The lungs have two sources of blood supply, the bronchial arteries which arise from the aorta and supply oxygenated blood to the bronchial walls, and the pulmonary arteries which circulate deoxygenated blood to the capillaries surrounding the alveoli.

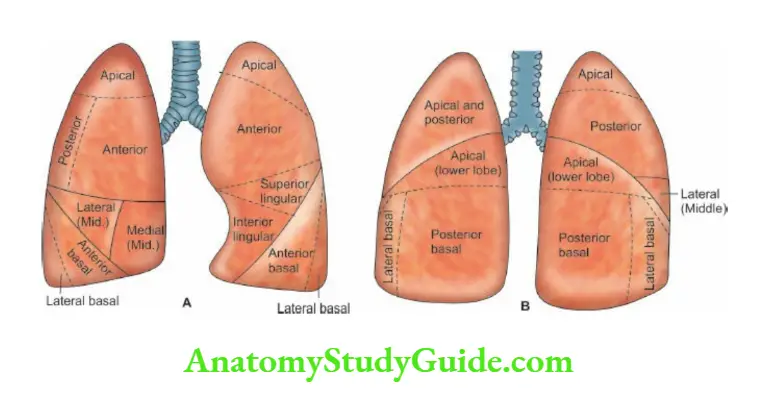

Surface anatomy The bifurcation of the trachea corresponds to an angle of Louis or Ludwig anteriorly and the 4th thoracic spine posteriorly.

The angle of Louis is a transverse bony ridge at the junction of the manubrium stern with a body of the manubrium.

The ribs and intercostal spaces are best counted downwards from the angle of Louis which corresponds to the second costal cartilage. It also provides a cutoff for superior and inferior mediastinum.

A line drawn from the 2nd thoracic spine to the 6th rib in the midclavicular line corresponds to the major interlobar fissure or upper border of the lower lobe of the lung.

The boundary between the upper and middle lobes is marked by a horizontal line drawn from the sternum at the level of the 4th costal cartilage to meet the major interlobar fissure line on the right side of the chest.

Mostly upper (middle also on the right side) and lower lobes are accessible to physical examination anteriorly and posteriorly respectively while all the lobes are accessible in the axillary area.

The surface anatomy of bronchopulmonary segments of lungs both in front and back is shown in.

History

Ask history of the present illness with special emphasis on onset (sudden, acute, subacute, or insidious), the evolution of the disease, and response to therapy.

The major symptoms of respiratory system disorder include fever, cough, coryza (viral URI or hay fever), sore throat, stridor, chest pain, and respiratory difficulty.

Mouth breathing with snoring during sleep occurs due to oropharyngeal obstruction (adenoids). Rattling or wet sounds may be audible due to secretions in the oropharynx and upper airways.

Rapid breathing with expiratory grunt (expiration through partially closed glottis to raise end-expiratory pressure) is characteristically seen in infants with hyaline membrane disease and bronchopneumonia.

Wheezing or predominantly expiratory whistling sounds are heard in children with an obstruction or spasm of small airways. Inspiratory stridor is characteristically heard in children with obstruction in the larynx or trachea.

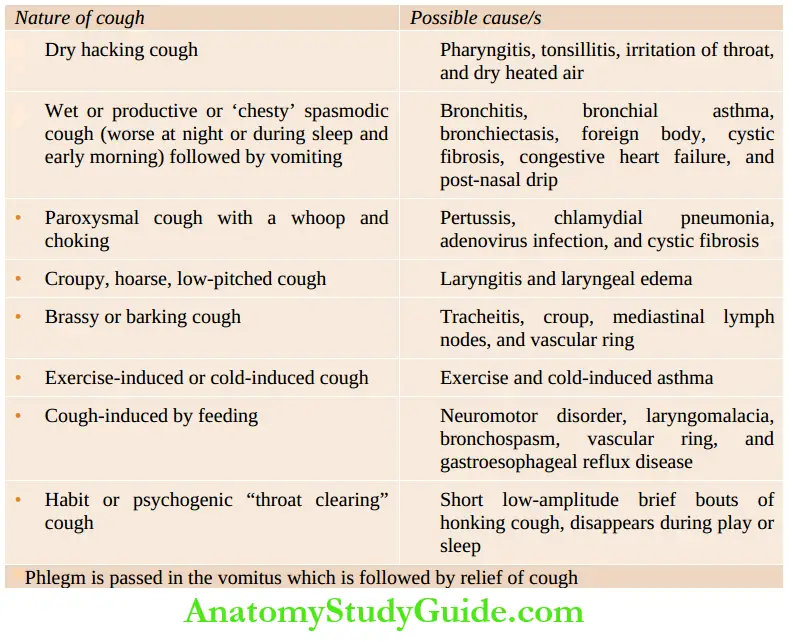

The nature and characteristics of cough may provide useful diagnostic clues. Ask whether the cough is mild or intractable, dry, or associated with bubbling sounds in the throat or chest, diurnal or predominantly nocturnal.

Cough aggravated by dust, aeroallergens, smoke, physical activity (exercise-induced asthma), cold water baths, and preservatives and synthetic colors in food, is suggestive of increased airway reactivity.

Nocturnal cough is common due to bronchitis, bronchial asthma, postnasal discharge, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and left heart failure.

Infants and young children cannot expectorate sputum and they often swallow it and may bring out the phlegm in the vomitus or pass it in the stools.

A spasmodic hacking cough is suggestive of bronchospasm, tracheitis, pertussis, cystic fibrosis, foreign body, and aspiration.

In cough-variant asthma, there are intractable bouts of spasmodic cough without any significant wheezing. Cough is a relatively uncommon symptom in neonates and may occur due to aspiration and chlamydial infection.

Inspiratory whoop following a bout of spasmodic cough is characteristic of pertussis but may occur in respiratory infections due to B.

parapertussis, adenoviruses and chlamydiae. A cough with copious putrid expectoration is suggestive of bronchiectasis and pulmonary suppuration.

There may be a history suggestive of measles, pertussis, and inhalation of a foreign body at the onset.

In children with recurrent respiratory infections, a detailed history should be taken to exclude inhalation of the foreign body as evidenced by a sudden and dramatic episode of life-threatening choking, cough, and cyanosis.

Ask for a history of abnormal sounds during inspiration (stridor) and expiratory grunting in pneumonia and wheezing in bronchiolitis and bronchial asthma.

Psychogenic cough is short bouts of low-amplitude “throat clearing” cough that disappears in school, during play, and at night. The cough is worse during stress, unfamiliar circumstances, and when a child is being watched.

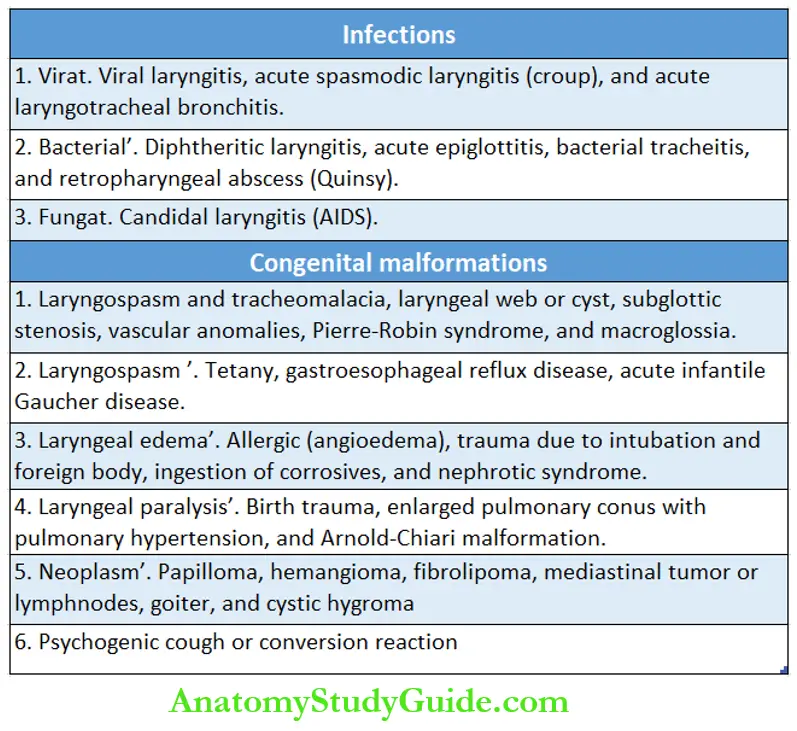

A stridor is a harsh, vibratory, high-pitched, shrill, or crowing noise caused by obstructed airflow.

The stridor may be inspiratory (upper airway obstruction), expiratory (lower airway obstruction below the level of the larynx), or biphasic due to mid-tracheal disorder.

The additional features of respiratory obstruction include hoarseness, hypoxia, brassy cough, tachypnea, and dyspnea with inspiratory retractions of the chest and the use of accessory muscles for respiration.

The incidence of respiratory obstruction is relatively high in infants due to the small size of the larynx, the presence of loose submucous connective tissue, and the rigid encirclement of the subglottic area by the cricoid cartilage.

The common causes of stridor are listed in. Tachypnea and dyspnea are suggestive of acute lower respiratory tract infection, bronchospasm, atelectasis, and compression of the lungs (pneumothorax, pleural effusion, mediastinal mass, diaphragmatic hernia).

Retractions of the chest are common and marked in children due to a soft rib cage. Marked suprasternal retractions are seen in upper airway obstruction.

The presence of cyanosis and feeding difficulty is suggestive of a life-threatening respiratory disorder requiring immediate hospitalization.

History of recurrent episodes of cough with breathing difficulty is suggestive of bronchial asthma, bronchiectasis, foreign body, left-to-right shunt, cystic fibrosis, immunodeficiency state, and gastroesophageal reflux.

Ask for a history of dysphagia which may be acute (acute pharyngitis or tonsillitis, diphtheria, acute epiglottitis, retropharyngeal abscess, etc.) or insidious (mediastinal mass, vascular ring) in onset.

Hemoptysis is uncommon in children and may occur due to bronchiectasis, lung abscess, resolving lobar pneumonia, pulmonary hemosiderosis, pulmonary edema, mitral stenosis, tubercular cavity, and bleeding disorder.

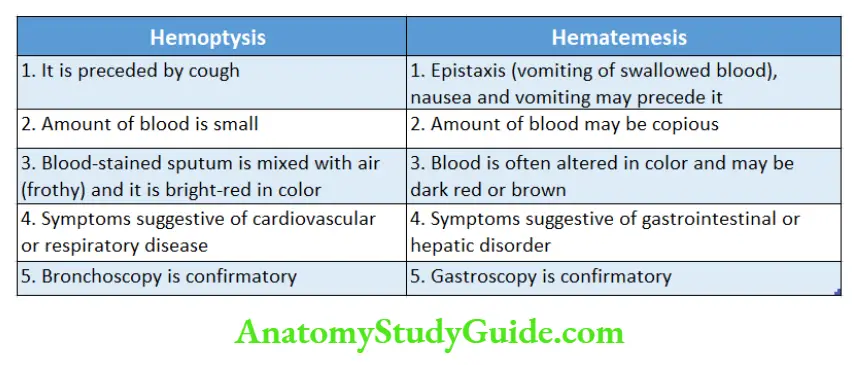

Unlike hematemesis, hemoptysis is preceded by a bout of cough, the blood is bright red in color, and usually small in quantity.

History of chest pain is uncommon and may occur due to pleurisy, pericarditis, pleurodynia, costochondritis, herpes zoster, trauma, and coronary insufficiency (severe aortic stenosis or regurgitation, anomalous left coronary artery from pulmonary artery, Kawasaki disease).

Common causes of hemoptysis

- Bacterial pneumonia (rusty sputum)

- Fibro-caseous tuberculosis

- Bronchiectasis

- Lung abscess

- Pulmonary sequestration

- Pulmonary edema

- Foreign body

- Cystic fibrosis or mucoviscidosis

- Mitral stenosis, pulmonary hypertension, or severe pulmonic stenosis

- Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis

- Bleeding disorder

Family history of tuberculosis, bronchial asthma, and hay fever should be asked.

Unsatisfactory living conditions, overcrowding, environmental pollution, parental smoking, and smoky chulla at home, are associated with increased incidence of respiratory infections and episodes of bronchospasm.

History of contact and allergy to pets may predispose to the development of rhinitis and bronchial asthma. Allergic manifestations may occur due to exposure to certain foods, artificial colors, and preservatives.

The vaccination status of the child should be enquired. It provides useful guidelines to assess the respiratory disorder and make a correct diagnosis.

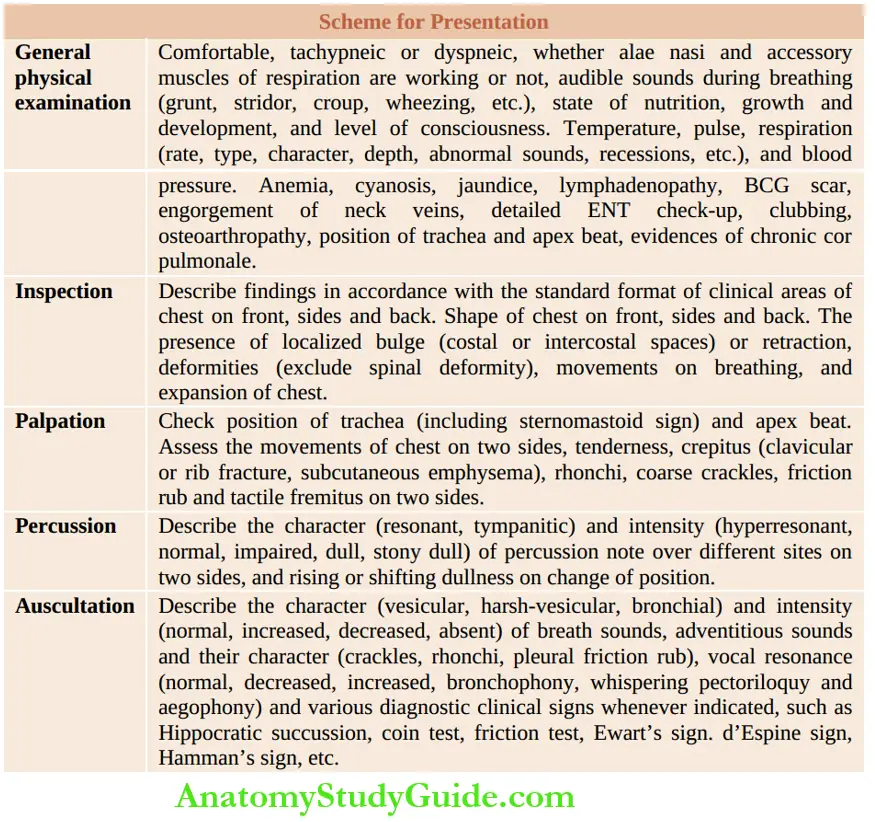

General Physical Examination

Assess whether the child is comfortable, tachypneic, or dyspneic. Look for any scars on the chest wall due to prior surgical procedures.

While recording history, note whether accessory muscles of respiration and alae na are working or not.

To improve the patency of the airway in acute epiglottitis, the child sits with his mouth open and drooling, tongue protruding, and head bent forward with the neck slightly flexed.

The child with pleural effusion is more comfortable with splinting the chest by lying on the side of the effusion.

Inspiratory dyspnea occurs due to obstruction of upper airways while expiratory dyspnea is seen in children with obstructive lung disease.

State of consciousness, build and nutrition, and putrid odor from the mouth should be noted. Audible sounds during breathing.

stridor, croup, hissing, grunting, stertorous, pharyngeal snores, and wheezing may be heard. Stridor is a harsh, vibratory, high-pitched crowing sound due to inspiratory obstruction to the airflow.

Grunting occurs when an infant makes expiratory efforts through a partially closed glottis to increase end-expiratory pressure to prevent the collapse of alveoli during expiration.

Nature of the cough whether intermittent, spasmodic, whoopie, metallic, bubbly, etc. should be recorded. Note the character of voice or cry.

Temperature, pulse rate, and its ratio to respiration (the normal ratio being 4 to 1) should be noted.

Respiration rate per minute, type of breathing rhythm (normal, reversed, Cheyne-Stokes, Biot’s breathing), character (normal, inspiratory distress, expiratory distress), depth (normal, shallow, deep or KussmauTs breathing) and suprasternal, intercostal, subcostal recessions and movements of alae na should be looked for.

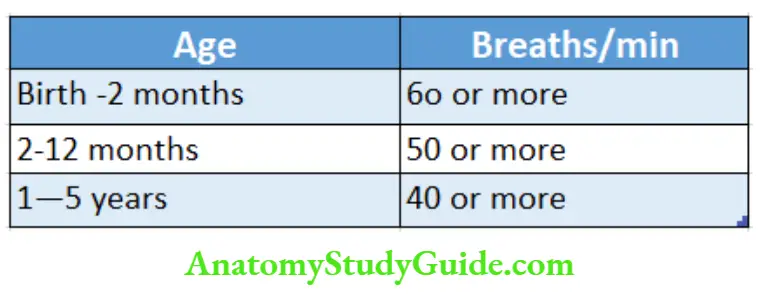

WHO cut-offs for fast breathing in under-5 children are given in. The normal rhythm of breathing is characterized by an inspiration expiration pause.

Reversed rhythm expiratory grunt inspiration pause is seen in children with an acute lower respiratory infection.

Deep sighing breathing or Kussmaul breathing occurs in response to metabolic acidosis due to severe diarrhea and dehydration, diabetic ketoacidosis, acute renal failure, lactic acidosis, an inborn error of metabolism, salicylate, and methanol poisoning.

Cheyne-Stokes breathing is characterized by temporary cessation of breathing (apnea) followed by respiratory efforts which gradually increase in magnitude to a maximum and then gradually diminish until apnea occurs once again.

It occurs due to depression of the respiratory center because of hypoxia, encephalitis or meningitis, increased intracranial pressure, uremia, and congestive heart failure.

Biot’s breathing occurs in children with raised intracranial pressure and is characterized by episodes of apnea followed by 4–5 irregular breaths (irregular nonrhythmic).

Anemia, cyanosis, jaundice, and lymphadenopathy should be looked for.

ENT checkup is essential to rule out upper respiratory tract infection, otitis media, and sinusitis. Examine the oral cavity and throat for any acute or chronic infection and the nose for any discharge and polyp.

- Itching of the nose (and eyes), upward rubbing of the nose with an open palm (allergic salute), horizontal crease over the nasal bridge, dark circles, and allergic “shiners” over lower eyelids, are suggestive of allergic rhinitis (hay fever).

- The sphenoid sinuses are present at birth and ethmoid and maxillary sinuses are of clinical importance during early childhood.

- The frontal sinuses are usually not present during the first 10 years of age. Chronic sinusitis is associated with nasal obstruction with persistent mucopurulent nasal discharge, slight puffiness of eyelids, and dark circles under the eyes.

- The important causes of chronic sinusitis include cleft palate, nasal allergy, Kartagener’s or immotile cilia syndrome, ataxia-telangiectasia, Hurler’s syndrome, cystic fibrosis, choanal atresia, and immunodeficiency disorders.

- Look for clubbing of nails and osteoarthropathy (clubbing with pain in the wrists and ankles).

- The presence of severely engorged non-pulsatile jugular veins is suggestive of mediastinal mass and may be associated with facial plethora, “brassy” cough, hoarseness, stridor, or dysphagia.

- Erythema nodosum and phlyctenular conjunctivitis may be associated with tuberculosis.

Look for a scar from BCG vaccination over the left shoulder. Subconjunctival hemorrhage, facial puffiness, suffusion of eyes, and subcutaneous emphysema may occur in children with pertussis.

Assessment of Respiratory Distress

The severity of respiratory distress is assessed by the following criteria:

- Mental status: Alertness, irritability, drowsiness, or ship rose

- The severity of tachypnea, dyspnea, and use of accessory muscles for breathing

- Color: Blue (cyanosis) or pale (shock)

- Pulsus paradox and its severity (>20 mm Hg difference in blood pressure during the end of inspiration and expiration)

- Arterial oxygen saturation <85% on pulse oximeter

- Peak expiratory flow rate of less than 80% of die predicted or an actual average of tire patients.

Peak Expiratory Flow Rate (PEFR)

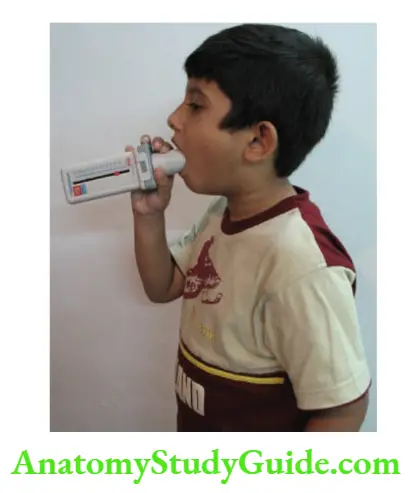

Children above the age of 5 years can be taught to use a peak flow meter to recognize an impending attack of wheezing. The marker of the die mini dow meter is slid to zero. The child is asked to stand up and take a deep breath.

- The mound-piece of die dow meter is then taken in die liquid and lips are tightly closed over it.

- The child is asked to exhale maximal effort and force. The procedure is repeated 3 times and die highest reading is recorded.

- The child can be asked to record his PEFR twice a day. It is a useful home device for early identification of an attack of bronchial addition and its severity. Depending upon die racial PEFR of die, child, and degree categories are identified.

- Green zone Peak expiratory flow rate within 80% of the predicted average (Patient’s known highest PEFR when wed) indicates that the patient is doing well on current medications (or without medications).

- Yellow zone Peak expiratory flow rate between 50% and 80% of the predicted or actual average PEFR of the patient is indicative of a mild attack and the need for stepping up the inhalation therapy on an ambulatory basis.

Red zone Peak expiratory dow rate of less than 50% of the predicted or actual average indicates a moderate to severe attack of bronchial asthma. The child should be immediately referred to the hospital for further management.

Acute Respiratory Failure

It is characterized by impending respiratory failure, apprehension, anxiety, restlessness, worsening of tachypnea, dyspnea, chest retractions, and cyanosis.

The air entry to the lungs may be severely compromised due to upper airway obstruction or marked bronco-space with minimal or absent breath sounds on auscultation.

The breathing may become slow, shallow and gasping, or irregular due to CNS depression and neuromuscular disease or terminally when respiratory muscles become exhausted due to overwork.

Pulse oximetry may show arterial oxygen saturation of <85% and PaO2 of <60 nun Hg in a FiO2 of >0.6 (in the absence of cyanotic heart disease) or PaCO2 of >50 nun Hg (hypercarbia).

Examination Of Chest

The ready availability of roentgenographic examination and advances in imaging technology have rusted the art of clinical examination of the chest. Anatomical areas for purposes of clinical examination of the chest are as follows:

Front: Supraclavicular, infraclavicular, mammary, and inframammary areas.

Side: Superior, middle, and inferior axillary areas.

Back: Suprascapular, interscapular, scapular, infrascapular and basal areas.

Inspection

The exposed chest should be inspected by standing at the head or foot side of the patient with eyes at the level of the chest.

The child, however, is best examined while sitting comfortably on a stool or standing with arms hanging limply by the sides.

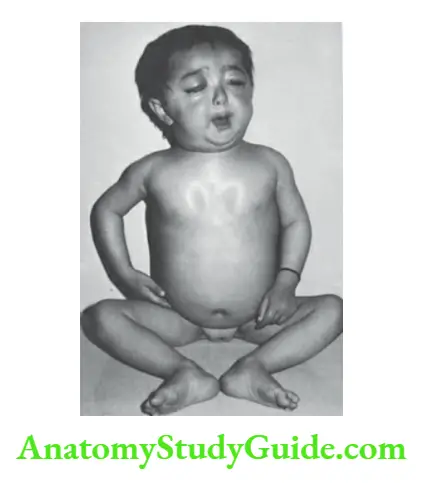

The shape of the chest is nearly circular or cylindrical in infants.

The shape may be normal, barrel-shaped or emphysematous, pigeon chest or pectus carinatum (rickets, chondrodystrophy, spondylosis dysplasia congenital, Noonan syndrome, Schwartz-Jampel syndrome, asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy, bronchial asthma), and funnel-shaped chest or pectus excavatum (rickets, absent pectoralis muscle, Marfan syndrome, mucosal neuroma syndrome).

Agenesis or hypoplasia of the pectoralis major may be associated with hypoplasia or absence of the breast and nipple (Poland syndrome).

Harrison’s sulcus (rickets, upper airway obstruction), kyphosis, and levo- or dextro-scoliosis of the spine should be looked for.

Costochondral beading (rickety rosary) may be the sole evidence of early rickets, his every child with a chest deformity, the spinal deformity must be excluded. Symmetry Note whether the chest is bilaterally symmetrical or not.

Note the distance of medial borders of scapulae from the midline on both sides which is useful to assess any asymmetry of the chest.

Drooping of one shoulder may occur in patients with fibrocaseous tuberculosis. Look for localized bulge (whether coastal or intercostal bulge) or retraction (collapse or fibrosis).

There is bulging of intercostal spaces in cases of pleural effusion or empyema.

When empyema points through an intercostal space as a cystic swelling, it is reducible, and cough impulse is present, it is called empyema necessitates.

The bony cage of the chest may show localized bulge due to long-standing cardiomegaly, intrathoracic mass lesion, and deformities of ribs and spine.

Movements of the chest The breathing is mostly abdominal or ab domino thoracic in infants. When the diaphragm is paralyzed, the upper part of the abdomen may be drawn in (instead of being forced out) with each inspiration.

In paralysis of intercostal muscles, there is very little expansion of the chest with the abnormal expansion of the abdomen with each inspiration.

The range of movements, respiratory lag on the affected side, and the indrawing of suprasternal, intercostal, and subcostal spaces should be looked for.

Marked suprasternal recessions are suggestive of narrowing or obstruction of upper airways due to laryngeal diphtheria, acute laryngotracheobronchitis, acute epiglottitis, laryngeal or tracheal foreign body, and angioneurotic edema.

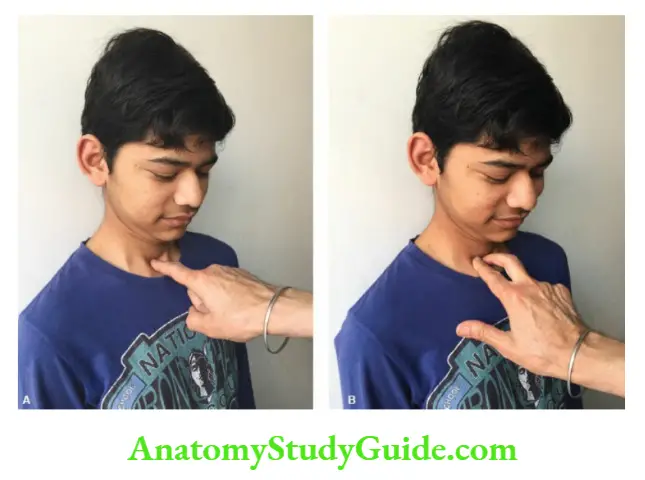

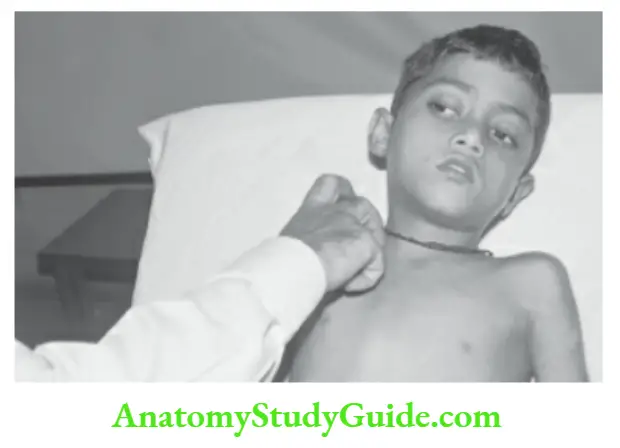

The position of the trachea and apex beat should be localized. The trachea is examined with a child in the supine position or sitting with slight flexion of the neck.

Place the index finger into the suprasternal notch, and gently push it backward. Normally the finger should touch the trachea in the midline.

If the trachea deviates, the finger will slide into the trachea-sternomastoid space.

In a child with marked tracheal displacement, the clavicular head of the sternomastoid muscle would be pushed forward as a visible bulge on the displaced side (sternomastoid or trail sign).

In normal children, the trachea may be slightly deviated to the right. The trachea may be pulled (towards the diseased side) due to collapse, fibrosis, and thickened pleura.

It may be pushed (towards the normal side) by pleural effusion, pneumothorax, and a mass lesion. Scoliosis may cause tracheal deviation and should be excluded.

Palpation

The findings of the inspection should be confirmed. Look for any tender areas, and crepitus (subcutaneous emphysema, fracture rib) and assess any differences in movements on two sides of the chest.

Feel for any abnormal vibrations, rhonchi, friction rub, coarse crackles, and characteristic spongy feeling of subcutaneous emphysema.

Vocal or tactile fremitus is looked for by comparing tactile transmission of spoken words (like one, two, three) or cry in infants, over identical areas on two sides of the chest.

It may be normal and equal on two sides or decreased/increased over a particular area. It has the same significance as vocal resonance but is unreliable in children.

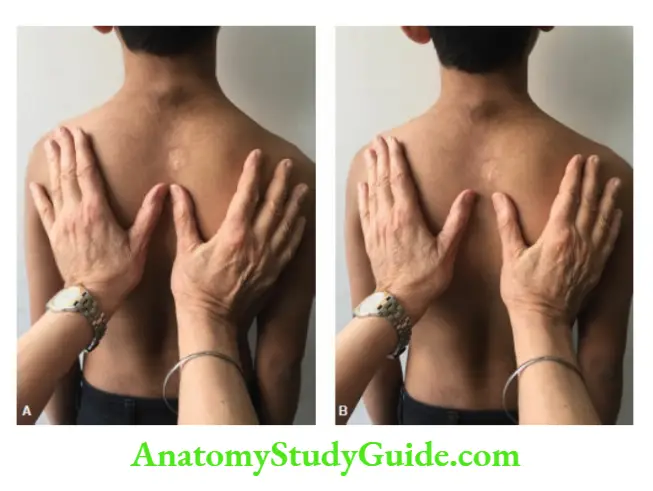

Assess the expansion of the chest on two sides. When pneumothorax is suspected in a newborn baby or infant, transillumination of the chest can be done with a fiber optic cold light source in a dark room.

The hemithorax will glow with light if there is pneumothorax and decompression can be done without delay.

Percussion

The pleximeter finger (middle finger of the non-dominant hand) should be placed in firm contact with the chest while the rest of the fingers should be lifted off the chest because they may dampen the resonance.

The pleximeter finger should be held parallel to the margin of the organ to be outlined.

It is kept parallel to the ribs except for eliciting mediastinal dullness when the pleximeter finger is kept vertical and percussed from the lateral to the medial side.

The pleximeter finger should move from the resonant towards the possible dull area.

The tap should be Tree’ and gentle and is best done with the middle finger (plexor) of the dominant hand by striking the middle phalanx of the pleximeter finger.

If the organ or tissue to be percussed is superficial, it is advised to do light percussion. For example, direct (without a pleximeter) light percussion over the clavicles is done to assess the apices of the lungs.

The strokes should be of uniform force and executed by movements at the relaxed wrist. The plexor finger must be withdrawn immediately after the stroke.

The intensity and quality of the sound produced and the ‘feeling’ of resistance imparted to the pleximeter finger should be observed. The identical areas of the chest on two sides should be compared simultaneously.

The chest may be normally or equally resonant on two sides, and there may be unilateral or bilateral hyperresonance (pneumothorax, emphysema), tympanitic note (large cavity, pneumothorax, diaphragmatic hernia), impaired resonance (consolidation, collapse, fibrosis), dull (consolidation, pleural thickening) or stony dull (pleural effusion or empyema) percussion note.

Rising dullness (higher level of dullness in the axilla as compared to the front and back) and shifting dullness (the level of dullness is more on lying down than on sitting up) should be looked for when the pleural effusion is suspected

Auscultatory percussion It is more reliable and informative than conventional percussion and can pick up small lesions to 3 cm in diameter especially hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes, pulmonary infiltrates, atelectasis, and patches of pneumonia.

The patient sits up with arms resting on his thighs. The examiner stands or sits on either side of the patient.

The examiner percusses over the manubrium by tapping lightly with the middle or index finger of the dominant hand while listening with the diaphragm piece of stethoscope applied snugly by the other hand over the posterior chest wall.

It must be ensured that percussion is applied with equal intensity over the same area of the manubrium while the stethoscope explores both lung fields by comparing the intensity and quality of percussion notes on corresponding anatomical areas from apex to base, the end, paravertebral areas are auscultated to detect possible mediastinal and Mar masses.

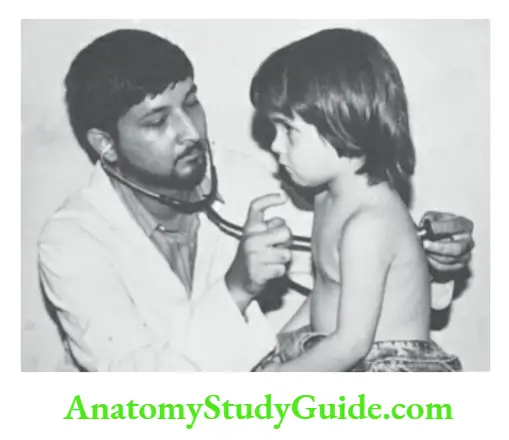

Auscultation

The infants and young children are best auscultated while the mother or father supports the child against the security of their shoulders.

Infants are uncooperative and may cry which may facilitate auscultation. Children above 2 years can be asked to take deep breaths during auscultation.

The character of Breath Sounds

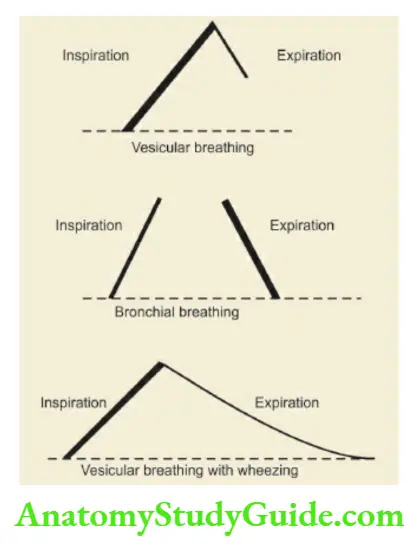

Vesicular The normal breath sounds produced in the alveoli are called vesicular.

The inspiration is loud, high-pitched, and long, there is no pause after the inspiration, expiration is low in intensity and short in duration and is followed by a pause.

In children, the normal breath sounds are puerile or harsh vesicular with slightly prolonged expiration

(bronchovesicular).

Bronchial The inspiration is low in intensity and is followed by a pause while the expiration is harsh, blowing, guttural, high-pitched, loud, and prolonged.

The duration of inspiration and expiration is almost identical. The sounds have definite tubular quality.

It may be normally heard over the neck and thoracic spine up to the 4th thoracic vertebra (trachea). Bronchial breathing may be of the following types

- High-pitched or tubular (consolidation)

- Medium-pitched (consolidation, small cavity, or atelectasis with a patent bronchus).

- Low-pitched or cavernous (large cavity)

- Amphoric (bronchopleural fistula). It is low-pitched bronchial breathing with metallic overtones.

The intensity of breath sounds may be normal, decreased, or absent on one or both sides. Vocal resonance It is similar to tactile vocal fremitus but is evaluated by auscultation and is thus more reliable.

Both tire intensity and quality of sound transmitted through the chest piece of the tire stethoscope are assessed when a child is asked to repeat some words (one, two, three) or cries.

The intensity of vocal resonance may be equal and normal on two sides, absent or decreased (pleural effusion, pleural thickening, pneumothorax, emphysema, atelectasis) or increased (consolidation, cavity, infarction, atelectasis with patent bronchus).

Bronchophony refers to increased vocal resonance when it is so loud that it appears as if tire sound is being produced in the earpieces of the stethoscope (consolidation, cavity).

The audible vocal resonance, when a child is just asked to whisper certain words is called a whispering pectoriloquy and is indicative of markedly increased vocal resonance (bronchopleural fistula).

The nasal twang or “bleating of a goat” quality of vocal resonance is called aegophony and is audible at the upper level of pleural effusion due to a partially collapsed underlying lung.

It is produced by selective transmission of high-frequency components of breath sounds.

Adventitious Sounds

The adventitious sounds may arise from the tire pleura or lungs.

Extrapulmonary adventitious or abnormal sounds may be heard due to shivering or rigors, rubbing of chest-piece over tire hairy skin or clothes, and crepitus produced in tire region of broken rib(s).

Wheezes or rhonchi These are dry musical sounds produced due to the narrowing of air passages.

The expiration is prolonged in an attempt to expel tire-inspired air through tire narrow air passages.

They are monophonic in character when there is a localized obstruction of a bronchus (foreign body, lymph node) or polyphonic when there is generalized airway obstruction (asthma and bronchitis).

The common causes of wheezing are listed in. They are classified based on their pitch and site of origin.

Common causes of wheezing

- Reactive airway disease due to asthmatic bronchitis

- Acute bronchiolitis or viral pneumonia

- Aspiration pneumonia or aspiration of a foreign body

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Cystic fibrosis or mucoviscidosis

- Extra bronchial pressure due to enlarged mediastinal nodes or endobronchial tuberculosis

- Vascular ring

- Lobar emphysema

- Isolated tracheoesophageal fistula

- Visceral larva migrant and Loeffler’s syndrome

- Cardiac failure or large left-to-right shunt

- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- Drug-induced: β-blockers, opioids, NSAIDs

- Conversion reaction

In these conditions, wheezing is usually unilateral.

1. High-pitched or sibilant rhonchi are produced in the bronchioles. They are audible during the end of inspiration or the beginning of expiration and are better appreciated by placing the chest piece in front of the infant’s mouth and nose (acute bronchiolitis).

2. Medium-pitched rhonchi are produced in medium-sized bronchi.

3. Low-pitched or sonorous rhonchi are produced in large bronchi. They are heard throughout both phases of breathing and are often audible even without a stethoscope.

4. When airway obstruction becomes extreme, the movements of airflow become minimal with the disappearance of breath sounds (silent chest) and rhonchi but worsening of the condition of the patient with impending respiratory failure.

Crackles They are short, explosive bubbling or wet sounds produced by the passage of air through the exudates collected in the alveoli, bronchioles, bronchi, or trachea.

The fine crackles are produced by the sudden opening of previously closed small airways of the alveoli. The older terms, like crepitations and rales, are no longer used. The nature and origin of crackles are given below:

1. Fine crackles produce a sound like the rustling of paper and are audible during the early phase of inspiration (bronchopneumonia, bronchiolitis, and congestive heart failure).

2. Medium-pitched crackles are heard in patients with bronchitis and resolving pneumonia and pulmonary edema.

3. Low-pitched or coarse crackles are audible throughout both phases of respiration and are loud in intensity (bronchiectasis).

The crackles must be differentiated from pharyngeal sounds or stertorous breathing and rattling sounds.

The pharyngeal sounds disappear after suction or by asking the patient to cough and are better heard by auscultation over the mouth and front of the upper neck, hi small infants, adventitious sounds from one side of the chest may be transmitted to the opposite side.

A pleural friction rub is produced when inflamed parietal and visceral pleurae rub against each other.

It is unaltered by cough (unlike crackles), is more localized, and is augmented by snug contact of the chest piece of the stethoscope to the chest wall.

It is heard during the identical phases of inspiration and expiration and has a peculiar superficial grating, creaking, and leathery character.

It increases in intensity when a chest piece of stethoscope is pressed against the chest wall.

If the pleura adjacent to the pericardium is inflamed, a pleuropericardial rub may also be heard.

It disappears when two leaves of pleura are separated by further accumulation of exudates. At times pleural rub may be palpable with tire palm. There may be localized chest pain.

Special Signs

Hippocratic succussion or succussion splash Whenever pleural effusion is suspected, splash should be elicited to rule out hydropneumothorax.

The chest piece is placed at the upper border of dullness and the child is suddenly shaken to elicit a splash of fluid.

Coin test coin is placed in front of the chest and tapped with another coin while the chest piece is placed at an identical spot on the tire back. A loud bell-like tinkle is audible in patients with pneumothorax.

Friction test The chest piece is placed on the tire center of the tire chest and friction is produced on either side of the chest wall with a wooden spatula or fingernail.

The conduction of tire sound is distinctly better when the chest is scratched on the tire side having pneumothorax.

Ewart’s sign The bronchial breathing and bronchophony may be audible over tire left the lower interscapular area in a patient with pericardial effusion due to compression of the left main bronchus leading to collapse.

D’Espine sign The presence of bronchial breathing and increased vocal resonance in tire midline over tire back below tire level of 4th thoracic vertebra in a patient with a mediastinal mass.

Mediastinal crunch (Hamman’s sign) In children with mediastinal emphysema, especially when associated with left-sided pneumothorax, systolic crunching sounds may be heard on auscultation over the left sternal border from third to fifth interspaces.

Mediastinal air leaks may be associated with crepitus over the tire supraclavicular region without any subcutaneous emphysema of the diest wall.

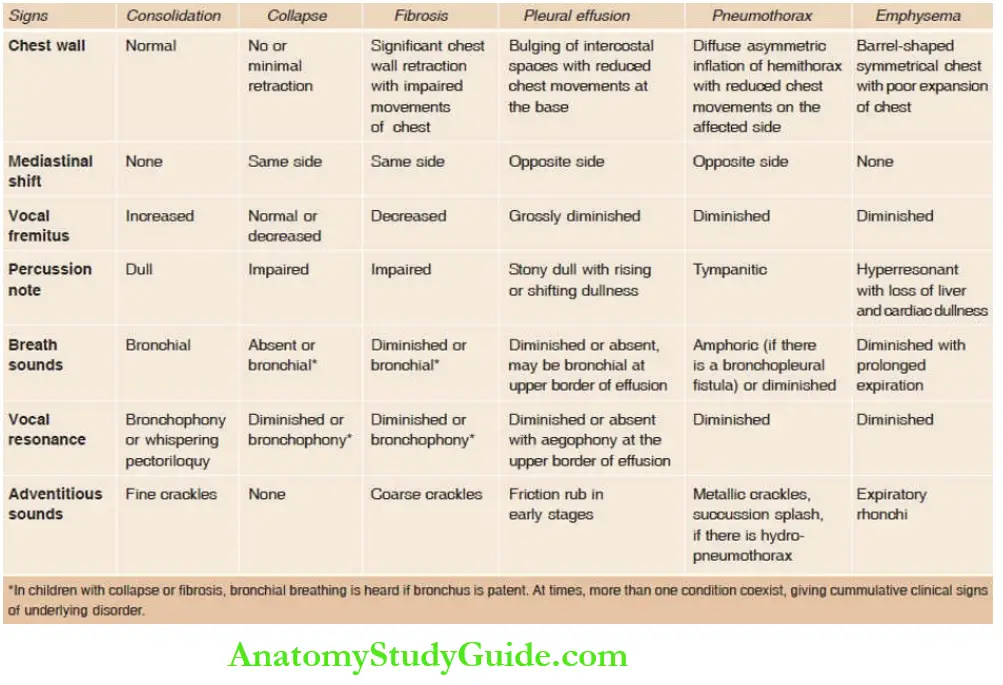

Diagnostic Features Of Common Respiratory Disorders

Tire salient physical signs of common diseases of the lungs in children are shown in Table.

Lobar Pneumonia (Consolidation)

Sudden onset of fever, cough, chest pain, dyspnea, and rusty sputum are characteristic symptoms. The trachea is central.

The chest movements may be slightly impaired on the affected side, percussion notes are dull, tubular bronchial breathing with crackles, and increased vocal fremitus and vocal resonance are classical signs of consolidation.

Pleural friction rub, overlying the site of consolidation, may be heard at times.

Pleural Effusion Or Empyema

There is a history of chest pain, breathing difficulty, fever, and cough. Onset may be sudden but is generally insidious. The patient prefers to lie on the tire-affected side, to splint the chest.

The trachea and heart are displaced towards the tire on opposite sides. The chest may be bulging (especially intercostal spaces) on the tire-affected side with reduced movements.

There is stony dullness, rising dullness and sometimes shifting dullness on the tire-affected side. Breath sounds are vesicular, diminished, or absent without any adventitious sounds. Tactile fremitus and vocal resonance are reduced.

Atelectasis Or Collapse

History of inhalation of foreign body, aspiration, and recurrent chest infections should arouse the suspicion of atelectasis.

The trachea and heart are pulled towards the side of atelectasis due to increased negative pleural pressure. Intercostal spaces may be narrowed on the affected side. The percussion note is impaired.

Breath sounds are reduced in intensity, vesicular or distant bronchial if connecting bronchus, is patent.

Vocal fremitus and vocal resonance are reduced or increased depending upon the patency of the connecting bronchus. The opposite lung may show compensatory emphysema.

Fibrosis

Thickened pleura, chronic infection with fibrosis, mucoviscidosis, and idiopathic interstitial fibrosis produce chronic respiratory insufficiency with dyspnea, cyanosis, and clubbing.

unilateral or localized, the chest is retracted and moves less on inspiration. Mediastinum is pulled towards the affected side. The percussion note is impaired.

Breath sounds are vesicular and reduced in intensity. Crackles are commonly present. Associated consolidation or collapse may produce additional clinical findings.

Evidence of chronic cor pulmonale may be seen in long-standing cases.

Pneumothorax

Sudden chest pain, dyspnea, and cyanosis herald the onset of pneumothorax. Subcutaneous emphysema may be evident over the neck and upper chest.

The trachea and heart are pushed towards the opposite side. The affected side shows hyperinflation and reduced movements in breathing. Percussion note is hyperresonant, or tympanitic.

Breath sounds are vesicular and reduced in intensity, and tactile fremitus and vocal resonance are reduced.

When there is a bronchopleural fistula, amphoric bronchial breathing with whispering pectoriloquy is audible. The coin test and friction test may be positive.

Leave a Reply