Principles And Art Of Examination Of Children

Prerequisites

- Physical examination is subjective (provides soft data) and its yield depends upon the experience, skills, thoroughness, and the time spent by the pediatrician for making the clinical assessment.

- Eyes, ears, nose, and palpating fingers are the real gems of a physician and an intact analytical brain is the necklace. Sharp, sensitive, and well-conditioned special senses are crucial for making correct observations.

- Sight (sharp and keen observation), hearing (listening, percussion, auscultation), smell (sickness, fetor hepaticas, uremia, ketosis, poisons, pus, metabolic disorders, etc.), taste (least important), touch (gentleness, healing, sensitive and delicate hands with long fingers), analytical, synthetic mind, intuition, and common sense are essential attributes of a successful physician.

Read and Learn More Pediatric Clinical Methods Notes

Table of Contents

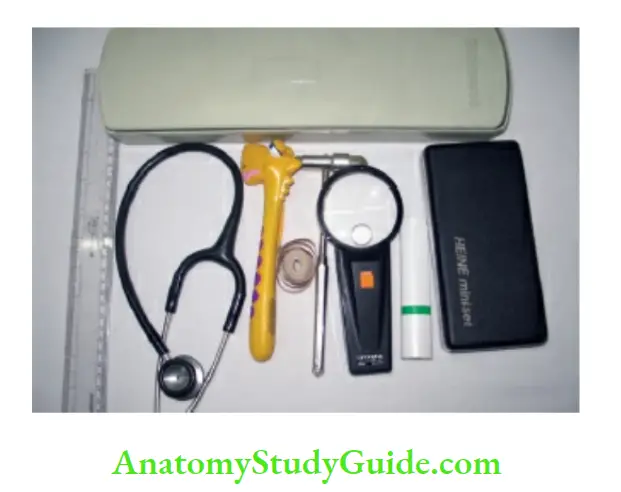

Essential Tools

- Stethoscope, torch, spatula, digital thermometer or aural thermoset, percussion hammer, fiberglass tape measure, white plastic ruler, diagnostic set, sphygmomanometer (with cuffs of different sizes), developmental assessment tools, weighing machine, infantometer for measurement of length and a wall chart or stadiometer for measurement of height should be available.

- Tools of different sizes are required because pediatricians are expected to deal with a preterm baby of under 1.0 kg and an adolescent of over 50 kg.

Physical Examination Setting

- A well-lighted, warm, colorful, comfortable room and warm hands are essential. The physical examination is often unsuccessful if the examiner has cold hands, cold instruments, and a cold manner.

- Toys, pictures, and cartoons are useful in the consultation chamber to allay the apprehension of the child. Avoid deep yellow/blue curtains which may interfere with the proper evaluation of jaundice and cyanosis.

Pediatrician Approach

- Gentleness, confidence, enthusiasm, patience, tact, compassion, concern, kind look, and love for children are essential attributes of a pediatrician.

- A good pediatrician begins his examination as soon as the mother enters the consultation room and while eliciting history.

- During the interview “sneaky” observation of the child, offering small bright objects or a soft toy, “intelligent neglect”, and respect for the mother/attendant to gain her/child’s confidence are essential.

- The best way to make friends with children is not to try! Avoid staring into the eyes of a child because, unlike adults, children distrust the man who looks into their eyes.

- The experienced pediatrician should be able to assess and grade whether a child looks well, is mildly ill, or is gravely sick requiring urgent attention.

Elicit Cooperation

- Parents should not spoil the image of the doctor by frightening children with threats of injections. When the family enters the consultation room, they should be greeted with a smile and a friendly demeanor.

- Children should be treated as children and not patients. While recording history, you can offer a toy to the toddler, in an unconcerned manner and without intently staring into his eyes.

- Let the child touch or play with the examining instruments, like a torch, stethoscope, and percussion hammer. You should adopt a playful attitude, and follow an unstructured approach.

- Physical examination of children should be fun both for the pediatrician as well as the child. The pediatrician should literally come down to the level of the child, both physically and mentally to elicit cooperation.

- If you are unable to obtain the cooperation of the child, it is usually due to your fault either because of lack of tact or unskillful approach.

- The previous experience with other physicians, the nature of the illness, the tact of a physician, unnecessary removal of clothes, and fixed sequence of examination are crucial determinants of whether a child is likely to cooperate or not.

- Unnecessary and complete undressing of the child is undesirable and often compromises cooperation. The undressing should be limited to the removal of some clothes at a time to facilitate specific aspects of the examination.

- Postpone examination or examine after sedation, if a child is uncooperative. The relatively traumatic examination, like percussion, throat, and rectal examination, should be done in the end.

- The older child may be explained the procedure if it is unpleasant. The child should be given a firm direction to follow instead of making a meek request which gives him the option to refuse to cooperate.

Position for Examination

To elicit maximum cooperation, children at different ages are best examined in different positions as shown in It is useful to have a revolving padded armless chair with a back for the mother and/or child to sit during the examination so that the position of the child can be easily changed by rotating the chair.

Most children feel comfortable sitting or standing during the examination rather than lying down on a bed. When the child appears friendly and not frightened, he may be placed on the examination table

The best position for examination at different ages

- 0–3 months Examination table

- 3 months-1 year Mother’s lap

- 1–3 years Standing or on mother’s lap

- After 3 years Examination table

- Adolescent girl Female attendant, mother, or nurse should be present at the time of examination

- Spend maximum time on observation. You can observe the whole infant at a time and it is the least disturbing to the child and most informative.

- Attitude and posture (bedridden or walking, opisthotonos or emperor-thorns, side posture, orthopneic, motionless, restless, comfortable), expression and mental state (fully conscious, drowsy, delirious, supposed or semi-comatose, coma) should be assessed.

- Abnormal movements, signs of meningeal irritation, peculiar odor, and the nature of the cry should be observed.

- Be alert for any characteristic odor (breath or urine) of the patient due to ingested poison, acetone (diabetic ketoacidosis), urinelike (azotemia), fruity smell (diphtheria), and a specific odor due to inborn errors of metabolism (like maple or caramel-like, musky or mousy, dried malt and “sweaty” feet). Never ignore the nonverbal communication of the patient.

- Pay due attention to the looks and anxiety on the patient’s face, the lowering of his eyes, the tremble in his hands, and the contents of his drawings.

- Develop a keen sense of observation during your day-to-day activities and by comparing different individuals to identify subtle differences in their facial features, phenotype, physique, posture, demeanor, gait, speech, etc.

- It is a unique quirk of nature that among millions of people no two human beings look alike! You can sharpen your observation skills by critically evaluating various characteristics and uniqueness of every person that you meet.

Sequence of Examination

- The approach to the examination should be unstructured to elicit cooperation and to ensure that maximum time is spent on the most relevant component of the examination.

- The unpleasant examination should be postponed to the end.

- Auscultation may be done at the beginning in an infant suspected to have a cardiac problem because a conventional sequence of examination would lead to crying by the time auscultation is done.

- This should be followed by an inspection, palpation, percussion, recording of blood pressure, elicitation of deep tendon jerks, ENT examination, rectal examination, and examination of the painful site or limb should be conducted in the end.

- Scheme of Recording and Presentation The presentation of physical findings should be standardized and recorded according to a set pattern though the sequence of examination of children is unstructured.

Scheme of Recording and Presentation

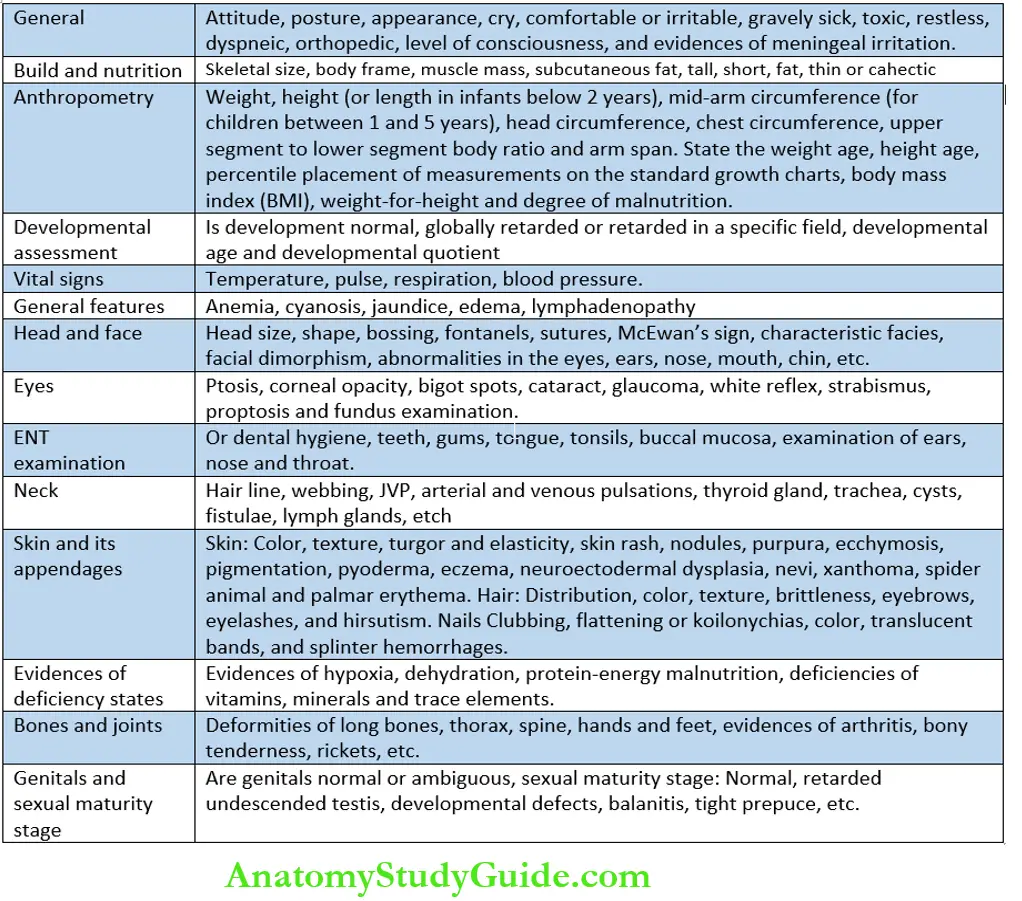

Scheme for recording general physical examination

- General appearance, build, and nutrition

- Anthropometry

- Developmental assessment

- Vital signs

- Head and face

- Eyes

- Ear, nose, and throat

- Neck

- Skin and its appendages

- Evidence of any deficiency states

- Bones and joints

- Genitals and sexual maturity rating

Anthropometry should be recorded by the nurse before a child enters the physician’s cabin

Build and Nutrition

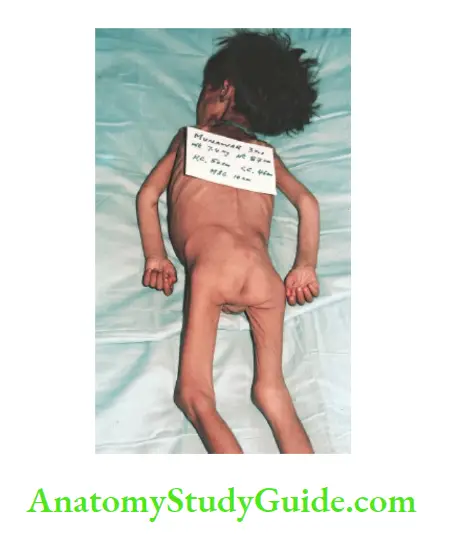

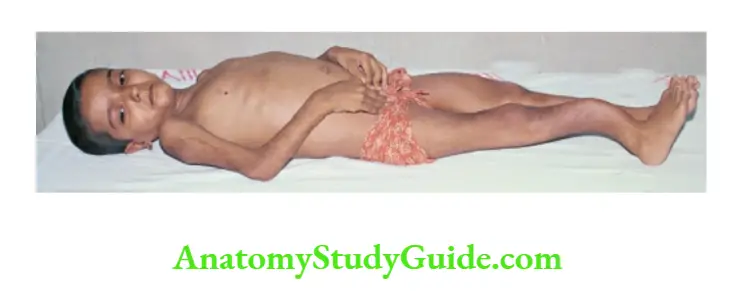

Skeletal size, body frame, subcutaneous fat, and muscle mass should be assessed. Is the child tall, short, fat, thin, muscular, asthenic, or cachectic? Look for clinical evidence of marasmus, marasmic kwashiorkor, and kwashiorkor.

3-year-old boy with marasmus. Note wasted extremities, poor muscle mass, loss of subcutaneous fat (skin hangs in folds over buttocks and thighs), and visible bony prominences

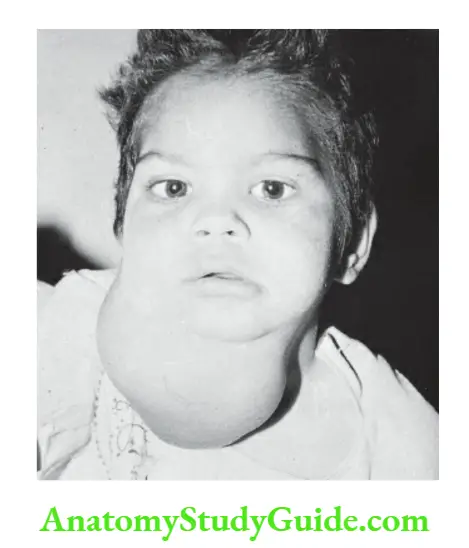

½-year-old girl with kwashiorkor. Note apathy, growth retardation, generalized edema, sparse hair, and crazy pavement dermatosis over the legs. There was hepatomegaly due to fatty infiltration of the liver

Measurements

Detailed anthropometry to record weight, height (or recumbent length with the help of an infantometer), surface area, body mass index, midarm circumference, stem length (crown rump or sitting height), arm span, upper segment (vertex to pubic symphysis) to lower segment ratio, chest circumference, and head circumference is essential for evaluation of children.

Developmental Examination

Objective assessment of development is required in selected cases. The dates for achieving target milestones should be recorded. Refer to Chapter 6 for details.

Vital Signs

- Temperature, pulse, blood pressure (Hess capillary test, Trousseau’s sign should also be looked for, if indicated), and respiration rate should be recorded.

- Femoral pulse must be examined which may be feeble or delayed (brachial delay) in patients with coarctation of the aorta.

- The breathing is relaxed and mostly abdominal or abdominothoracic in infants and it becomes predominantly thoracic after the age of 5 years.

- In critically sick children, blood pressure and capillary refill time should be checked. Press the pulp of the finger or upper sternum for 5 seconds to blanch it.

If it takes more than 2 seconds to refill or flush, it is suggestive of impending shock or poor circulation.

- Conventional thermometers (skin, oral, rectal) contain mercury in glass or are digital by using electronic technology.

- Skin temperature (groin and axilla) is recorded in infants and preschool children and is quite reliable.

- The axilla or groin should be dried with a cloth and the bulb of the thermometer is placed snugly by tightly holding the arm against the chest or flexing the thigh over the abdomen.

- The thermometer should be left in place for at least 2 minutes before reading the temperature.

- Skin temperature is 0.4°C (0.7°F) lower than the oral temperature, while rectal or eardrum temperature is 0.4°C (0.7°F) higher than an oral temperature.

- In school-going children, the oral temperature is recorded by placing the thermometer under the tongue and asking the child to breathe through the nose.

- Oral temperature is the reference temperature and fever is diagnosed when it exceeds 100°F (37.8°C). The oral temperature should not be taken immediately after intake of a hot or cold drink.

- The rectal temperature may be recorded in critically sick children but should be avoided as a routine office or domiciliary procedure.

- The rectal thermometer has a bulbous tip with a red mark compared to the long tip of the oral thermometer.

- While recording rectal temperature, a thermometer should be introduced by directing its tip posteriorly towards the backup to a maximum depth of 2.5 cm.

- Temperature can also be recorded over the skin of the forehead and eardrum by using thermos-crystal strips and infrared technology with the help of a thermos respectively.

These methods are quick and convenient but unreliable at times.

- They are operator dependent and not reliable in infants and children with wax in the ear canal.

- In severely malnourished children and neonates, a low-reading thermometer (30–40°C) should be used to assess the severity of hypothermia.

- Heads of most infants feel warm to touch due to increased blood flow to the brain and it should not be mistaken for fever.

- Due to their constitution, some children have warm hands while others may be endowed with relatively cold hands and feet.

- During episodes of fever, elevation of body temperature is usually associated with peripheral vasoconstriction leading to the development of cold extremities.

- In critically sick children, cold extremities are indicative of circulatory collapse or shock.

- It should be remembered that many normal children have diurnal variations in their body temperature, being lowest early morning and highest in the evening around 4 PM.

- Mild elevation of temperature (oral temperature up to 37.7°C or 99.9°F) in some children especially during the afternoons in summer months is not indicative of any disease process.

- Avoid unnecessary workup, if a child is otherwise well, active, playful, feeding, and growing normally.

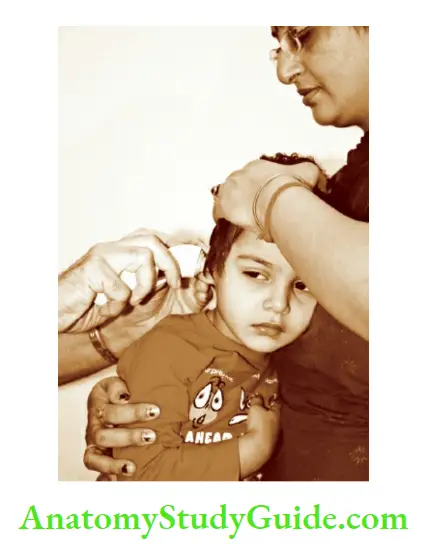

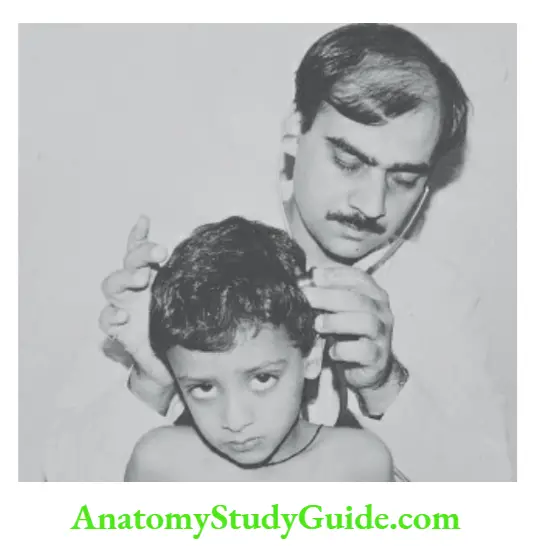

Recording the temperature of the eardrum with a thermostat which works on the principle of infrared technology.

The ear should be pulled outward in an infant and upward and outward in an older child for proper exposure to the eardrum. It is useful in a busy ambulatory clinic because temperature read-out is obtained within one second.

Tourniquet test (Hess capillary resistance test, Rumpel-Leed test). The sphygmomanometer cuff is wrapped around the upper arm and inflated midway between systolic and diastolic blood pressure for 5 minutes.

The skin of the forearm is examined 5 minutes later. The development of more than 10 petechiae over an area of one square inch on the flexor surface of the forearm is considered positive and suggestive of increased capillary fragility or thrombocytopenia.

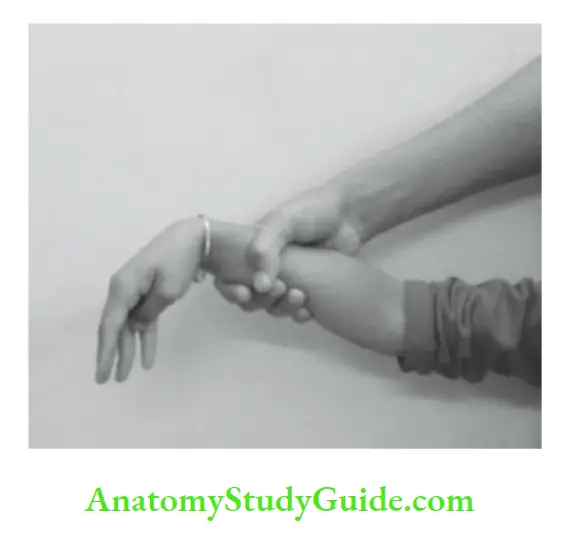

If the test is negative on one side, it may be repeated on the other arm. Trousseau’s sign. The blood pressure cuff is inflated above the systolic blood pressure for 3 minutes.

The increase in muscle tone over thenar eminence and adduction of the thumb is suggestive of positive Trousseau’s sign and is indicative of hypocalcemia.

The sign can be elicited by firmly compressing the forearm for one minute. The peroneal sign can be elicited by applying the blood pressure cuff over the thigh and keeping the cuff inflated above the systolic blood pressure for 3 minutes.

Anemia, lymphadenopathy, cyanosis, jaundice, and edema are looked for during general physical examination. Look for the pallor of the palpebral conjunctiva, tongue, and palms as a marker of anemia.

Anemia may be overdiagnosed in a child, with a fair complexion. In a sick child, arterial oxygen saturation should be assessed with a hand-transcribed pulse oximeter.

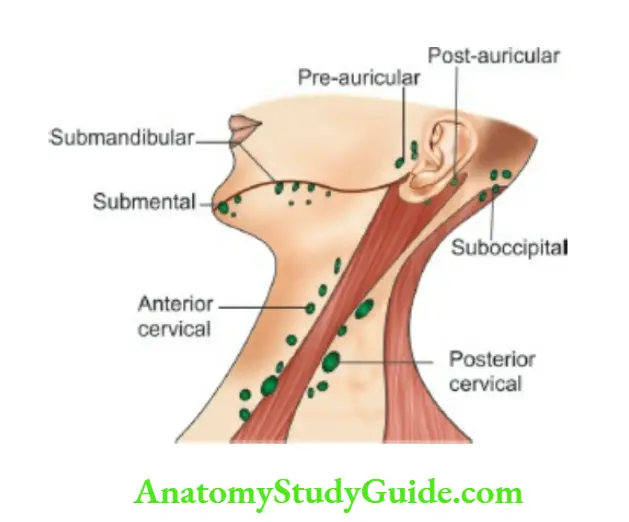

SaO2 or SpO2 of less than 90% in a neonate and 93% in an older child is suggestive of hypoxia. The peripheral lymph nodes are examined in the neck, axillae, epitrochlear region, groins, and popliteal fossae.

Axillary nodes are examined by keeping the patient’s arm slightly abducted and using the fingers of the left hand for the right axilla and vice versa.

The examination of lymph nodes should include their location or site, size, consistency, tenderness, and warmth, whether discrete or matted, mobile or fixed to the overlying skin.

Matted lymph nodes are characteristically seen in chronic inflammation due to tuberculosis. Discrete rubbery or firm lymph nodes are suggestive of malignancy or Hodgkin’s disease.

There is physiological hyperplasia of lymphoid tissue in children. Cervical lymphadenopathy up to 1.0–1.5 cm diameter, when lymph nodes are discrete, mobile and non-tender is not significant.

Cervical lymph nodes readily enlarge in children having pediculosis, pyoderma, and recurrent upper respiratory infections. Press the medial malleolus or shin for 5 seconds to look for pitting edema.

In infants, puffiness and sacral edema are more common. Edema due to lymphatic obstruction is usually nonpitting.

The location of lymphatic glands in the neck. The cervical lymph nodes are grouped into horizontal and vertical chains.

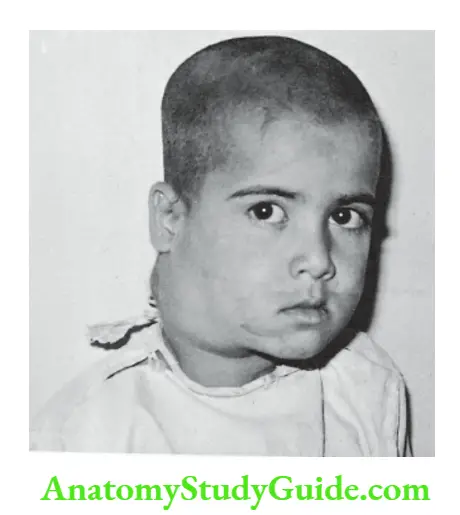

Typical appearances of cervical lymphadenopathy in a child with Hodgkin’s disease. The glands are mobile, discrete, and rubbery in consistency.

Head and Face

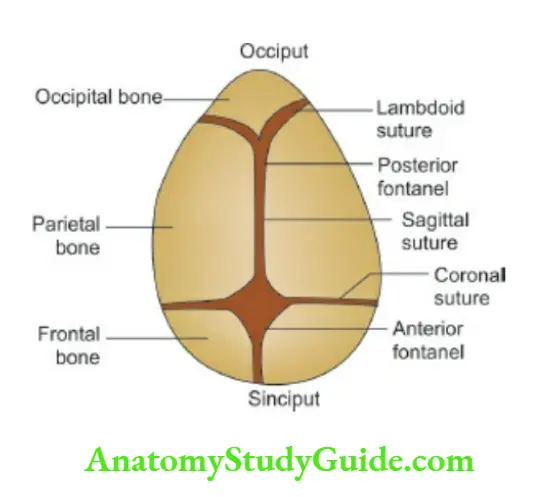

Look for size, shape, symmetry, bossing or prominences, anterior fontanel (size and tension), and sutures.

There are six fontanels at birth, of which two are large and midline (anterior and posterior fontanels) and four are small and not palpable (two anterolateral and two posterolateral).

shows the skull bones, sutures, and fontanels at birth. The fontanels should be examined when the baby is quiet and the head is kept upright.

Look for the size of the anterior fontanel and whether it is depressed, flat, or bulging. When intracranial tension is raised, the fontanel starts bulging and feels tense, and becomes non pulsatile.

A bulging and pulsatile anterior fontanel in a crying infant is of no significance. The anterior fontanel is depressed or sunken when there is significant dehydration.

The posterior fontanel is small at birth and closes by 6 weeks of age while the anterior fontanel measures 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm and usually closes by 10–18 months of age.

Auscultation and transillumination of the skull are indicated in infants with unexplained cardiac failure or large head

Macewen’s sign or cracked-pot sound is elicited by the percussion of the skull. The amplified sound may be listened with the help of a stethoscope.

The sign is positive when sutures are separated due to raised intracranial tension. It is physiologically present during infancy as long as the anterior fontanel is open.

Transillumination of the skull is indicated in all infants below one year of age.

A flashlight equipped with a rubber foam cuff is snugly applied over the frontal and occipital areas in a dark room and a rim of translucency is looked for.

When translucency extends beyond 2.0–2.5 cm in the frontal area and over 1.0 cm in the occipital region, it is abnormal and is indicative of subdural effusion, subdural hematoma, hydrocephalus, hydranencephaly, and porencephaly.

Intracranial bruit should be looked for in infants with raised intracranial tension and intractable congestive heart failure. It may be heard in 10 to 15% of normal children.

Macewen’s sign. The cracked-pot sound on percussion of the skull is evident to naked ears but can be heard better when amplified through the stethoscope.

It is indicative of separated sutures due to raised intracranial tension but is normally present if the anterior fontanel is open.

The odd-shaped skull may occur due to premature fusion of skull sutures because skull bones grow at a right angle to the direction of the sutures.

The anteroposterior diameter may be increased (dolichocephaly) or decreased (brachycephaly).

The skull may appear grossly asymmetrical (plagiocephaly), may grow vertically like a tower (oxycephaly, acrocephaly) or appear like a boat (scaphocephaly).

In the cloverleaf skull, all the cranial sutures are prematurely fused and the brain grows through the anterior and temporal or anterolateral fontanels producing projections or bulges at the vertex and temporal areas.

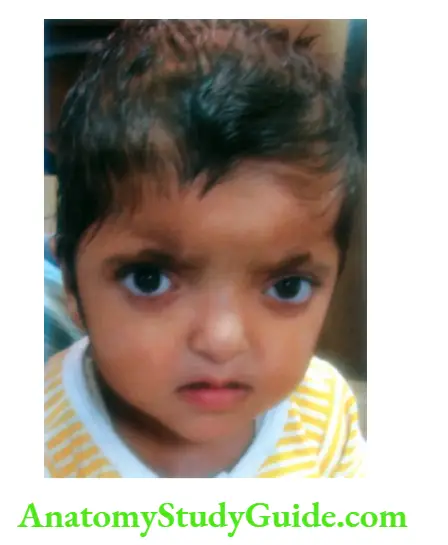

Characteristic facies, like Down syndrome, cretin, Gargoyle, chromosomal disorders, and evidence of facial dysmorphisms, like the asymmetry of the face, size, and position of ears, the distance between eyes, alignment of eyes, nasal bridge, lips, and chin, etc.

Should be looked for. Develop a keen sense of observation to identify minor features of dysmorphism. Lips also mirror the abnormalities seen in the oral mucosa.

Perleche or angular stomatitis is caused by nutritional deficiency or candidal infection. Cheilosis is a form of fissuring and cracking of lips which may occur due to drooling and vitamin B complex deficiency.

Rhagades are moist radiating lesions over the philtrum due to persistent nasal discharge in infants with congenital syphilis.

Salivary Glands

Look for swelling of salivary glands and their openings in the oral cavity. The major salivary glands include three pairs of parotids, submandibular and sublingual glands.

Parotids are located in front of the angle of the jaw just below the lobule of the ear. The parotid duct (Stenson duct) is located opposite the crown of the second upper molar teeth.

The swelling of the parotid gland lifts the ear lobule laterally which is best seen when a child is viewed from behind.

Submandibular glands are walnut-sized paired structures located beneath the angle of the jaw under the posterior ramus of the mandible.

Its duct is present under the tongue on either side of the frenulum. Sublingual glands are located under the tongue and they drain their secretions in the floor of the mouth.

Apart from major salivary glands, there are numerous tiny glands called minor salivary glands which are located in the lips, buccal mucosa, and throat.

They are not visible to the naked eye in normal circumstances. Salivary glands produce saliva, which moistens the oral cavity, tongue, gums, and lips.

It washes and inactivates bacteria, initiates the digestion of food, and protects teeth from decay.

Examine for any swelling of salivary gland(s), foul breath, and dryness of mouth or drooling due to excessive production or accumulation of saliva.

Eyes

The eyes are the windows of the central nervous system. The palpebral conjunctiva of the lower eyelids is examined by pulling down the lower eyelid and asking the child to look upwards.

To expose the palpebral conjunctiva of the upper eyelid, ask the child to look downwards and pull the upper eyelid upwards and evert the eyelashes by placing the left thumb just below the upper edge of the orbit.

Grasp the eyelashes between the forefinger and thumb of the right hand and evert the lid by rotating it around the left thumb.

Look for the pallor of palpebral conjunctiva (anemia), xerosis, and bigot spots over the temporal side of the corneoscleral junction (vitamin A deficiency) and circumcorneal vascularization (riboflavin deficiency).

Conjunctivitis is common in children and is characterized by redness and chemosis of the conjunctiva with purulent discharge and sticky eyelids.

Look for any bulging, prominence, and proptosis of one or both eyes. Style or hordeolum is a localized, tender swelling at the edge of the eyelid with a yellow punctum due to a staphylococcal infection.

Chalazion or meibomian cyst is a firm, discrete, nonpainful, flat nodule on the bulbar conjunctival aspect of the lid adjacent to the tarsal plate.

The presence of lilac or heliotropic discoloration and scaly dermatitis of eyelids with periorbital edema and telangiectasia are. pathognomonic of dermatomyositis.

Look for developmental defects, like epicanthic folds, slanting of eyes, ptosis, cataracts, coloboma (partial absence of a part of the eye), glaucoma, cloudy cornea, corneal opacity, white reflex (cataract, retinoblastoma), exophthalmos and setting-sun sign.

Increased distance between the inner canthi of eyes (hypertelorism) with or without epicanthic folds and slant of eyes should be looked for.

A cataract is best examined with the light of an ophthalmoscope wherein the red reflex is replaced by leukocoria or white reflex.

Examine the eyes through the +10 diopter lens of an ophthalmoscope from a distance of 10 inches from the child’s eyes.

Coloboma or absence of part of The iris (with or without the involvement of choroid and retina) may occur in association with dermal hypoplasia, trisomy 13, CHARGE association, and Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome.

Aniridia or complete absence of iris is rare and may be associated with Wilms’ tumor, Rieger syndrome, and neoplasms of the adrenal cortex and liver.

Heterochromia of irides (different colors of the iris of two eyes either partially or completely), may be associated with iridocyclitis of Fuchs, Waardenburg syndrome, Parry-Romberg syndrome, Sturge-Weber syndrome, Hirschsprung’s disease, Horner syndrome, and cervical or mediastinal neuroblastoma.

Kayser-Fleischer ring, a golden-brown or golden-green ring at the limbus of the cornea, may be seen with a hand lens or slit-lamp examination in patients with Wilson disease, cholestatic syndromes, and cholestatic hepatitis.

Heterochromia of the iris may occur due to injury or foreign body in the eye and following topical medications for glaucoma (prostaglandin analog).

Brushfield spots (“salt and pepper” speckling of the iris) may be seen on the naked eye or slit-lamp examination in children with Down syndrome.

Irodenesis, a quivering movement of the iris, may be caused by the dislocation of the lens in patients with Marfan syndrome and homocystinuria.

Examine the eyebrows and eyelashes which may be sparse or absent in children with ectodermal dysplasia.

Due to unexplained reasons, children with protein-energy malnutrition and tuberculosis may have relatively long eyelashes.

Long and curly eyelashes with bushy eyebrows which extend to the nation over the middle of the forehead (synophrys) are a characteristic feature of Cornelia de Lange syndrome.

The size of pupils and pupillary reflex to light and red reflex in each eye separately and both eyes simultaneously should be checked with the help of a direct ophthalmoscope in a dark room.

When indicated, the fundus should be examined for papilledema, optic atrophy, cherry-red spot, chorioretinitis,flame-shaped hemorrhages (bacterial endocarditis), leukemic deposits, and inflammatory granulomas (tuberculomas, candidemia).

Squint is checked by shining the torch light on the eyes of the child. When eyes are normally aligned, the light reflex should be visible at an identical position in both eyes.

When strabismus is present, a cover test is done to assess the primary and secondary deviation of the eyes.

The child is asked to fix the torch light or a toy held in front of the face. Suddenly cover one eye, the uncovered eye will make some corrective movement (primary deviation) for fixation, if a squint is present.

Now look at the eye behind the cover while keeping it shielded from the light or object.

In concomitant squint, the deviation of the shielded eye (secondary deviation) will be equal to the primary deviation while in the case of paralytic squint, the secondary deviation is more than the primary deviation.

Concomitant or non-paralytic squint is more common in children and is characterized by

- Onset before 3 years,

- Normal movements of eyeballs in all directions,

- Absence of diplopia or double vision,

- Primary and secondary deviations are equal and

- The deviating eye has defective vision or amblyopia. The concomitant squint may be convergent or divergent, constant or intermittent, may be monocular, or affect both eyes alternately.

Ear, Nose, and Throat

Evidence of vitamin B complex deficiency, angular stomatitis, and cheilosis should be looked for.

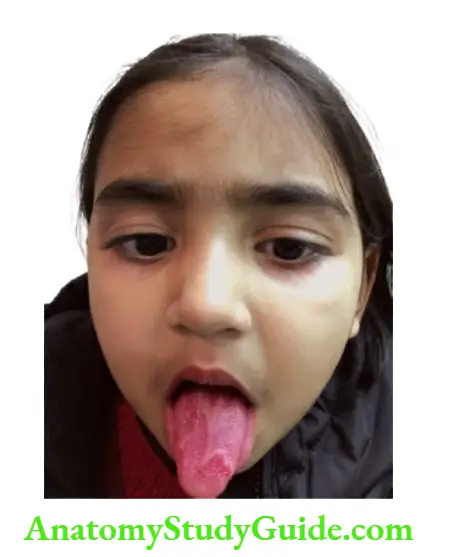

The tongue should be examined whether it is dry or wet, coated or clean, color, papillae, tremors, symmetry, aphthous ulcers, fissuring, etc.

The geographic tongue is characterized by irregular red patches of desquamated epithelium and filiform papillae with sharp whitish-yellow borders giving the appearance of a map over the tongue.

The patches may change size and shape and are of no significance. Tongue-tie or ankyloglossia is often blamed by the grandmother when a child is believed to have delayed speech.

It is uncommon and should be suspected if the frenulum is thick and tight causing midline depression in the tip of the tongue.

It neither causes difficulty in feeding nor delay in speech. Beefy-red smooth tongue due to atrophy of papillae is a recognized feature of vitamin B complex deficiency.

Strawberry tongue is characterized by white, swollen fungiform papillae standing against a raw, beefy-red background in children with scarlet fever, Kawasaki disease, and toxic shock syndrome

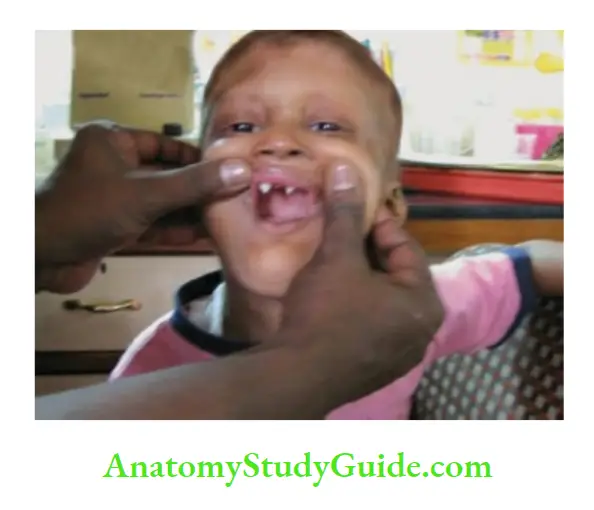

Teeth and gums should be examined for dental hygiene, gingival hyperplasia (phenytoin therapy), and bleeding manifestations.

A blue line on the gums is diagnostic of lead poisoning. Note how many deciduous or permanent teeth have erupted.

The timing of the onset of primary dentition is variable (due to genetic or constitutional factors) and is unreliable for the assessment of nutritional status.

Primary dentition may be delayed up to one year due to constitutional factors.

Milk teeth are white in color and have a smooth edge in contrast to permanent teeth, which have an ivory-white or off-white color and have a finely serrated edge.

Look for Koplik’s spots in all children presenting with upper respiratory tract infection to diagnose measles during the prodromal stage.

They are pinhead-sized white spots (like sago) with a red margin and are distributed over the buccal mucosa opposite the molar teeth.

In mumps, look for redness and edema around the opening of Stenson’s duct (opposite second upper molar). Examine throat in all children for the size of tonsils, evidence of inflammation, follicles, membrane, and petechiae.

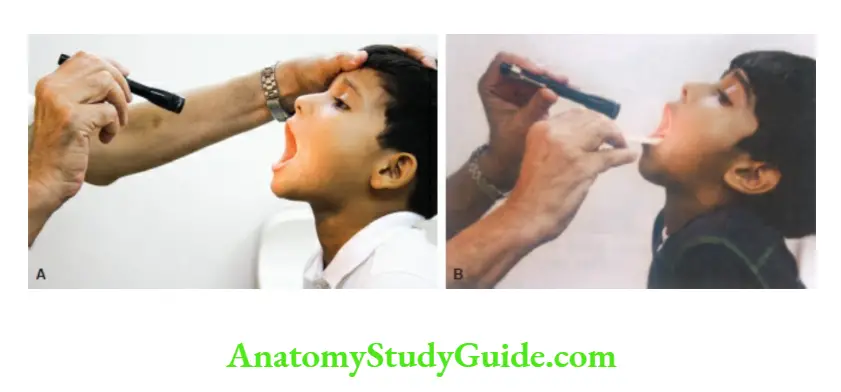

In children above 3 years, the throat can be examined without a spatula by asking the child to open the mouth and say “Aaha….”.

Herpangina is an acute febrile illness due to coxsackie viruses A and B, echoviruses, and enteroviruses.

It is characterized by dysphagia because of the development of painful 1–4 mm size papulovesicular lesions surrounded by an intense zone of erythema which are located mostly over the anterior tonsillar pillars and soft palate.

Aphthous ulcers due to herpetic infection are seen over the anterior aspect of the oral cavity involving the gums, buccal mucosa, and tongue.

Deviation of one tonsil towards or across the midline occurs due to peritonsillar abscess (quinsy).

Tonsils are physiologically large in most children. Small and atrophic tonsils may be seen in children with immunodeficiency disorder or may be absent following tonsillectomy.

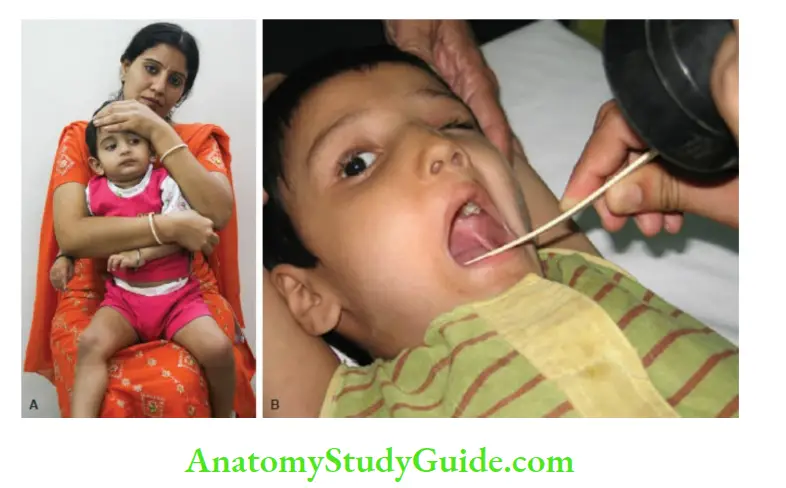

The mother or nurse is asked to restrain the child by immobilizing his head and holding both upper limbs. The throat can be examined both in sitting 1 and supine 2 positions.

The neck should be slightly extended and crying actually helps to see the throat. In patients with stridor or suspected epiglottitis, no attempt should be made to examine the throat by inserting a spatula as it may lead to complete airway obstruct

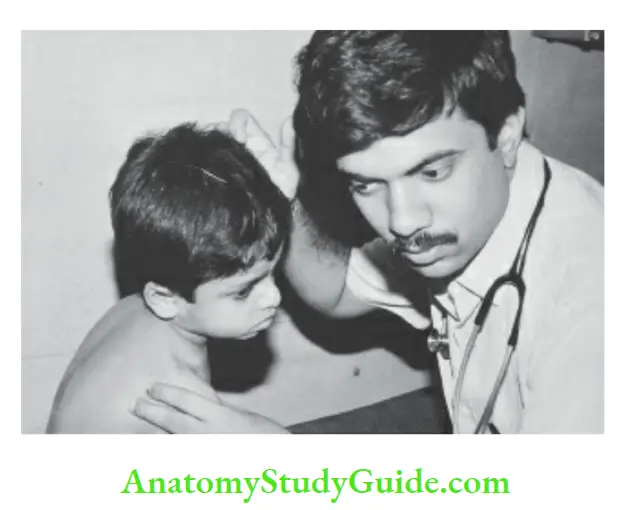

Throat being examined without any restraint in a 5-year-old boy. The child is asked to open their mouth widely and say “Aaha…”. In most cases, the throat can be examined without using a spatula.

The nose should be examined for any discharge (watery or purulent yellow or green), congestion or blockage, erosions or bleeding from Little’s area, polyps, deflected nasal septum, snuffles, and foreign body.

Nasal itching, transverse crease over the bridge of the nose, allergic “shiners” or dark circles under the eyes may be seen in children with allergic rhinitis.

Children with enlarged adenoids are likely to have an open mouth, drooping of the jaw, drooling of saliva, protrusion of teeth, and expressionless face.

They are uncomfortable at night, sleep with their mouth open, prone to snoring, sleep apnea, and recurrent episodes of middle ear infection.

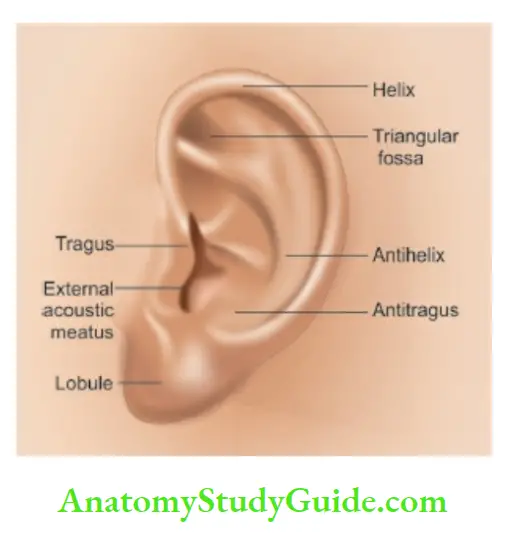

Alae na may show movements with each breath in infants with respiratory distress. External ears should be examined for their size, shape, location (normal or low set), and anatomical landmarks.

Look for pre- and post-auricular skin tags or sinuses which may be associated with renal malformations.

Potter facies (squashed face with a receding chin, low-set ears, and prominent skin folds below the eyes) is a characteristic feature of oligohydramnios due to bilateral renal agenesis.

The ear canal and middle ear should be examined in all children with unexplained fever, upper respiratory tract infection, ear ache, or discharging ear.

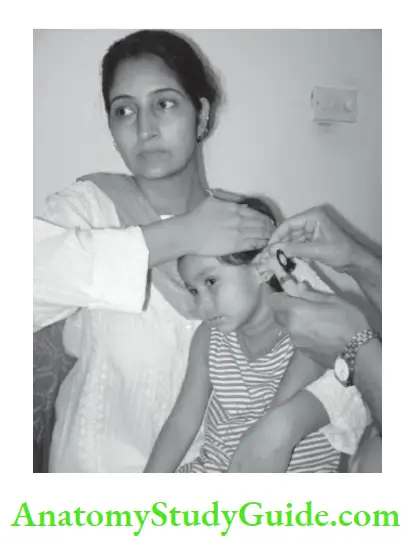

The child should be positioned properly and restrained for ease of examination.

In newborn babies and infants, the direction of the ear canal is upwards while in older children it runs outwards and upward.

To visualize the tympanic membrane, pull the pinna of the ear with the thumb and index finger upward and backward in older children and outwards or laterally in infants and newborns.

Use the largest speculum that will fit the ear canal.

The hand holding the otoscope should rest against the cheek or head of the child so that, if the child moves, the otoscope moves accordingly without imposing any risk to the child.

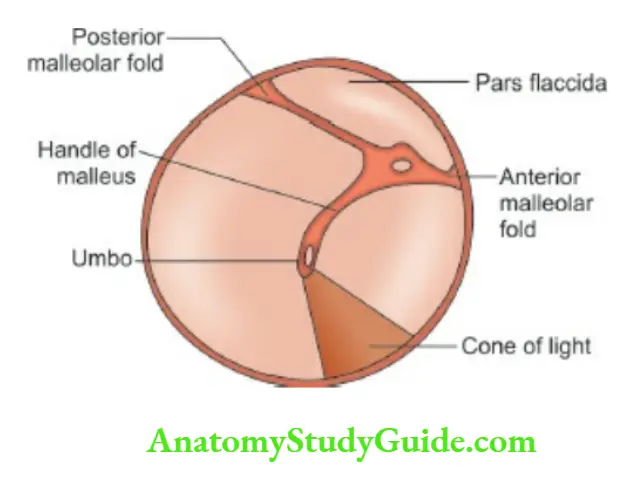

Look for secretions, wax, foreign body, and inflammation in the ear canal. Examine the tympanic membrane for its color, clarity, bulging or retraction, cone of light, and perforation.

The absence of a cone of light indicates a loss of luster due to inflammation. The common types of perforation are anteroinferior, subtotal (rather large in size), and attic over the par flaccid.

Position and restrain the child for an otoscopic examination of the ear. The mother or attendant should be asked to hold the child firmly to avoid any damage to the ear canal.

Neck

The neck is short in children and should be examined for any swelling, webbing, hairline, jugular venous pressure (JVP), arterial and venous pulsations, thyroid gland, lymph nodes, cysts, fistulae, and position of trachea.

Minor enlargement of the thyroid is better seen than felt and swelling moves upwards on swallowing.

The thyroid gland is best palpated from behind with both hands on either side of the neck.

When the gland is enlarged, assess whether it is uniform or nodular, soft or hard in consistency. In thyrotoxicosis, a bruit is usually heard over the goiter.

The tilting of the neck should be differentiated from torticollis by examining the head from behind.

In torticollis, the occiput is tilted to one side and the chin to the other while in head tilting both the occiput and chin are tilted to the same side.

Look for cystic swellings like dermoid or sebaceous cysts and thyroglossal cysts in the midline.

A dermoid cyst is attached to the overlying skin while a thyroglossal cyst is attached to the underlying structures and it moves upwards when a child is asked to protrude the tongue.

Lymphangioma or hygroma of the neck is a soft, boggy, compressible, and transilluminate swelling which may extend into the upper thorax.

Branchial cleft cysts may develop in adolescent children just in front of the upper third of the anterior border of the sternomastoid muscle.

They appear as smooth, discrete, movable, tense cystic swelling(s) varying between 1 and 5 cm in size. When the cyst ruptures, sticky, clear, and mucoid secretions are drained.

Skin and its Appendages

Examine nails of hands and feet for clubbing, koilonychia or flattening, splinter hemorrhages, Osler nodes, brittleness, and translucent bands.

Pitting of nails along with thickening and ridging may be seen in psoriasis, fungus infection, and atopic dermatitis.

White spots (leukonychia) or white lines may occur due to trauma or acute illness but are usually of no significance.

Dystrophic or dysplastic nails may be seen in children with ectodermal dysplasia, nail-patella syndrome, a dystrophic form of epidermolysis bullosa, fetal alcohol, and phenytoin syndromes.

Koilonychia or spooning of nails as a sign of iron deficiency is relatively uncommon in children.

The skin should be examined for color, texture, elasticity/turgor, pigmentation, hemorrhagic spots, erythematous rash (blanches on the pressure as opposed to petechiae and ecchymoses), pyoderma, subcutaneous nodules, neuroectodermal dysplasia, nevi, xanthoma, spider nevi, palmar erythema.

Follicular hyperkeratosis or phrynoderma is characteristically seen over extensor surfaces of forearms and buttocks.

It occurs due to nutritional deficiency of vitamin A and essential fatty acids.

The nature and distribution of skin lesions, whether isolated or generalized, symmetrical or asymmetrical, centrifugal or centripetal, present on flexor or extensor surfaces or areas exposed to sunlight should be looked for.

The morphology of skin lesions is described as macules (areas of discoloration, neither raised nor depressed), papules (elevations up to 5 mm diameter), nodules (larger than papules), vesicles (blisters up to 10 mm diameter), bullae, wheals (pale, flat papules with surrounding erythematous flare as seen in urticaria), scales, burrows (dark brown straight or sinuous elevations in interdigital areas produced by female scabies mite), comedones (blackheads of acne), plaques (circumscribed flat areas of skin felt either raised, depressed or thickened), ulcerations, erosions or scar formation, etc.

Look for distribution, color, texture, brittleness of scalp hair, and presence of seborrhea and lice.

Rarely hair may show alternate bands of depigmentation producing typical flag-sign in children with chronic malnutrition.

For a detailed examination of skin and its appendages, refer to Chapter 9.

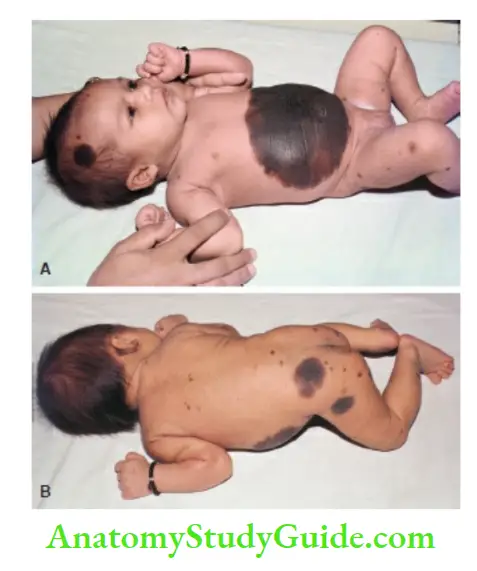

Giant pigmented nevus over the abdomen (1). There are smaller pigmented nevi over the face, back, and buttocks (2).

Dermatoglyphics

The pattern of creases and ridges over the palms may provide useful information of clinical significance in children.

Single horizontal palmar crease or Simian crease (due to merging of head and heart lines) is classically seen in children with Down syndrome or as an isolated minor anomaly and it may occur in association with other chromosomal disorders.

When there are two transverse creases and the proximal one runs across the entire palm (Sydney line), it is seen in congenital rubella syndrome.

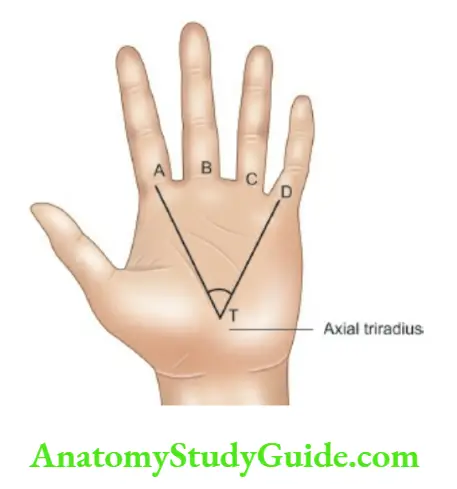

Distal triradii are seen over the bases of the index (1), middle (2), ring (3), and little (4) fingers while the proximal triradius (T) is located on the palm close to the wrist.

The ATD angle in normal subjects measures 40°.

The ATD angle is obtuse (between 75° and 80° due to the distal location of the axial triradius) in children with Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, and congenital Rubella syndrome.

There may be abnormalities in the pattern of ridges over fingertips in children with Down syndrome (ulnar loops in all fingers), congenital rubella syndrome (mostly whorls), trisomy-18 (increase in arches), and Klinefelter syndrome (marked reduction in ridge count)

Single palmar crease and ATD angle by joining AD distal triradii with axial triradius (T). ATD angle becomes obtuse when the axial triradius is shifted distally towards the fingers.

Evidence of Deficiency States

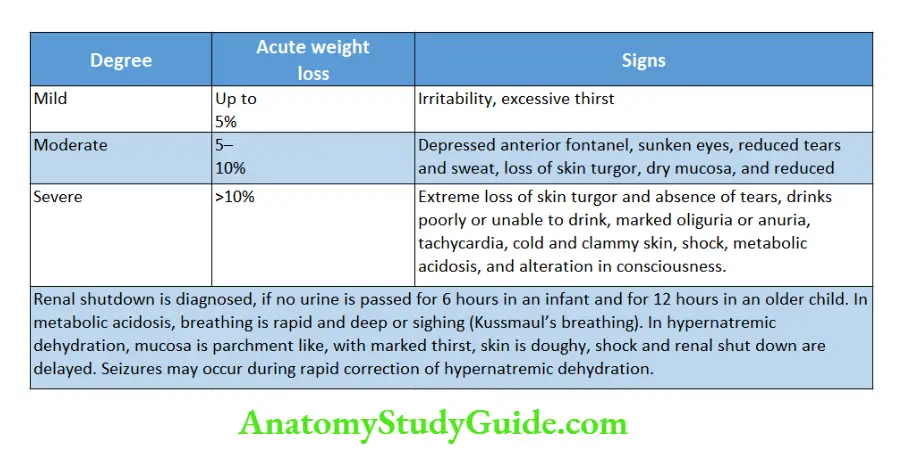

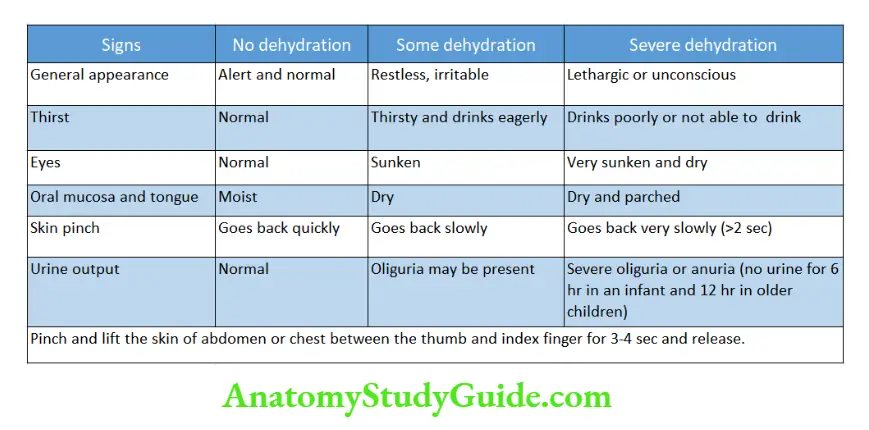

When the pre-illness weight of the child is known, the severity of dehydration can be assessed accurately by the degree of weight loss.

But most of the time accurate pre-illness weight of the child is not known and the severity of dehydration is graded as per WHO recommendations.

In marasmic children, skin turgor is impaired due to the loss of subcutaneous fat. The severity of dehydration is thus overestimated in malnourished children.

They may have sunken eyeballs, flat fontanel, and poor skin turgor without any dehydration.

You should look for evidence of excessive water loss (vomiting, diarrhea) or poor intake, excessive thirst, dry tongue or buccal mucosa, oliguria/anuria, acidosis and shock (cold extremities, tachycardia, feeble radial pulse, delayed capillary refill time of >2 sec) for making the diagnosis of dehydration in malnourished children.

On the other hand, in chubby or obese children, dehydration is likely to be overlooked or underestimated.

When a child is in the hospital and being weighed daily, sudden weight gain or weight loss are reliable correlates of overhydration (over-infusion and cardiac failure) and dehydration respectively.

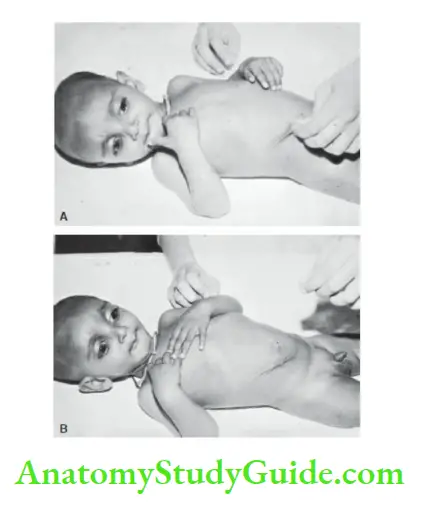

Method for elicitation of skin turgor. The abdominal skin is pinched, lifted, and released (1). When skin turgor is lost due to dehydration (or marasmus) it takes several seconds before the pinched skin assumes its unwrinkled appearance (2). Note the sunken eyes of the child.

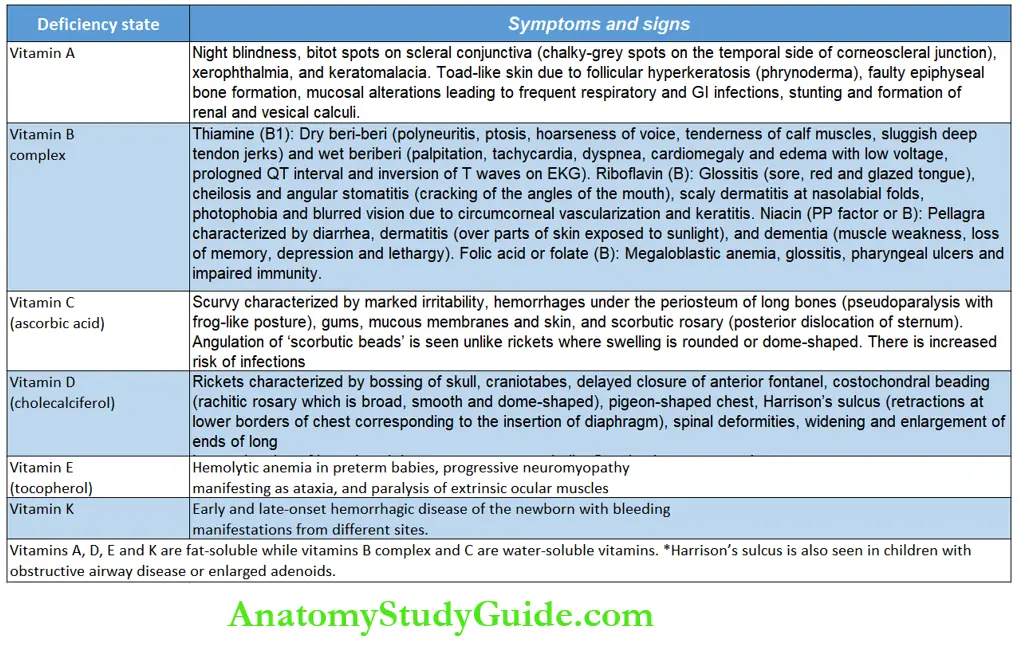

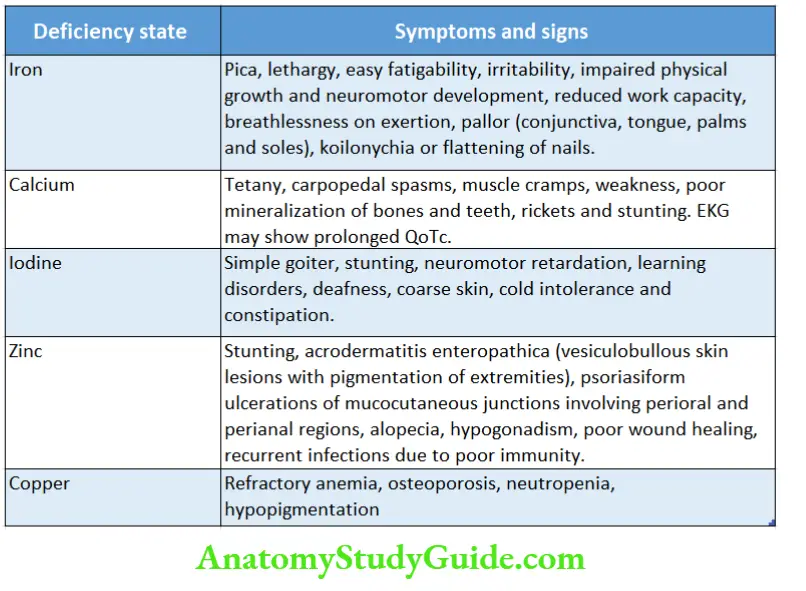

Look for evidence of protein-calorie deficiency (undernutrition, marasmus, marasmic kwashiorkor, kwashiorkor), deficiency of water-soluble (vitamins B complex and C) and fat-soluble (vitamins A, D, E, K) vitamins, and deficiencies of various minerals, like iron, calcium, iodine, copper, and zinc

Bones and Joints

Look for chest deformity, localized swelling, ends of long bones, sternal tenderness, joint inflammation, swelling, mobility of joints, size, and symmetry of limbs.

Arthralgia (joint pain alone) and arthritis (joint pain with swelling and inflammatory signs) should be differentiated.

Migratory or fleeting joint pain is suggestive of acute rheumatic fever and gonococci.

Examine hands and feet for their size, shape, and length of fingers and toes, dermatoglyphics, syndactyly, and polydactyly whether preaxial (towards the side of the thumb) or postaxial (towards the side of the little finger).

Examine fingers for clinodactyly (deflection of a finger) and camptodactyly (fixed flexion of interphalangeal joints producing clawlike appearance).

Hands and feet may look short and stubby because of the shortening of metacarpals and metatarsals.

In children with pseudohypoparathyroidism, the index finger may be longer than the middle finger because of the shortening of all metacarpals except the second.

Look for deformities, like club foot (plantar flexion, inversion, and adduction of foot) and calcaneal deformity (dorsiflexion and eversion of foot).

Bowed legs are normally seen during the first two years of life while slight knock knees are common between the ages of 2 to 5 years.

The severity of bowed legs is assessed by measuring the distance between the knees when medial malleoli are closely aligned in a supine infant.

For assessment of the severity of knock knees, the child is asked to stand with knees barely touching each other and the distance between medial malleoli at ankles is measured.

The physiological severity of bowed legs and knock knees is limited to 5 cm.

The arch of the feet is obliterated by a pad of fat during the first 2 years of life producing physiological flat feet.

Skeletal deformities due to renal rickets in a 10-year-old child. There is failure to thrive, widening of ends of long bones, mild costochondral beading, and marked deformities of bones of lower limbs (saber tibia).

In children with a history of arthralgia or arthritis, the mobility of joints should be tested in all directions.

Limitation of internal rotation is an early sign in many diseases of hip joints particularly slipped epiphysis and Legg-Perthe’s disease.

Excessive external rotation of hips is a common finding in infants up to 18 months.

Curvature (kyphosis, lordosis, scoliosis), swelling, tenderness, and range of movements of the spine should be looked for. Spinal deformity may account for displacement of the apex beat.

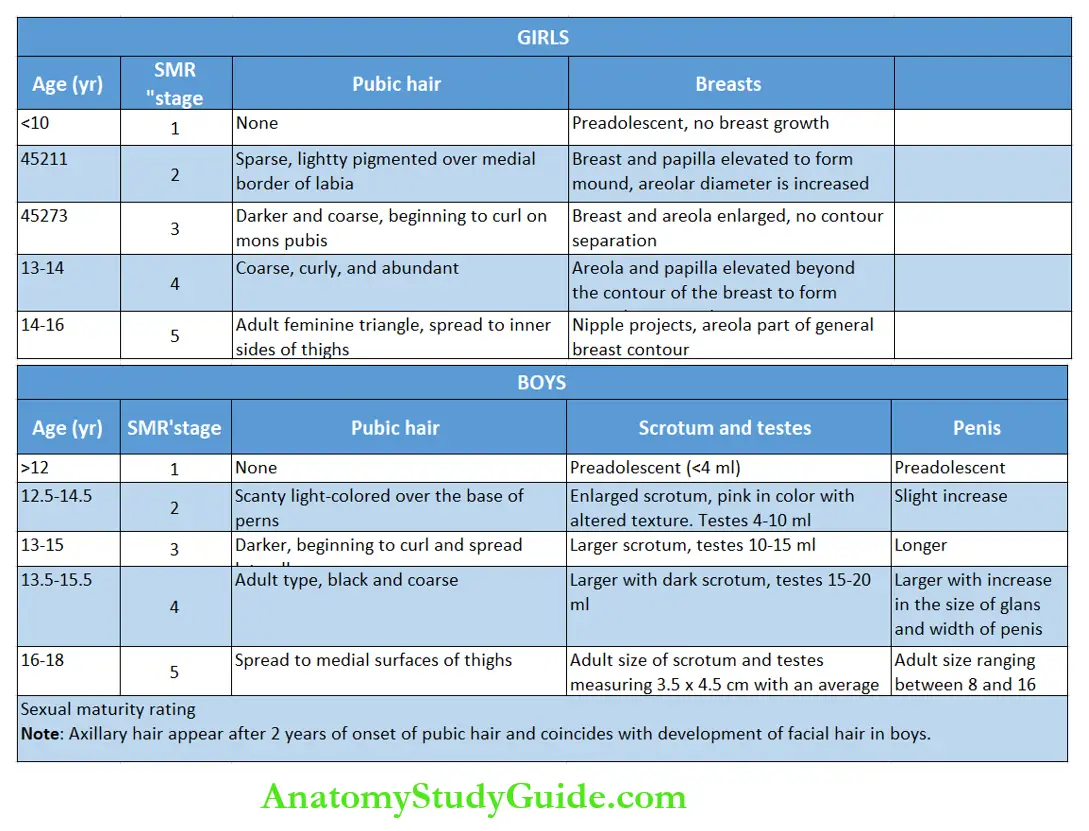

Sexual Maturity Rating

Adolescence extends from 10–16 years in girls and 12–18 years in boys. Adolescence and sexual maturation are earlier by 2 years in girls compared to boys.

The age of onset of puberty is variable but usually occurs between 10–12 years in girls and 12–14 years in boys.

Breast development is the first manifestation of sexual development in girls while testicular enlargement heralds the onset of sexual maturity in boys.

A prader orchidometer or tachometer (Beads of different volumes ranging from 1.0 to 25.0 ml) can be used to accurately assess the testicular volume.

In preadolescent obese boys, the penis may be embedded in the pubic fat giving an erroneous impression of hypogonadism.

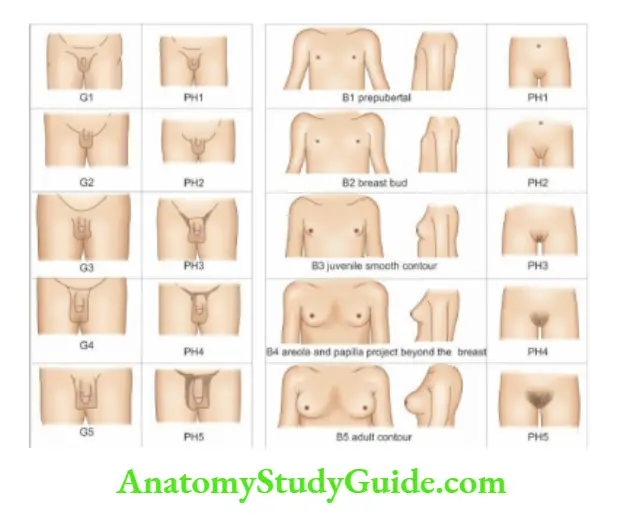

The stages of sexual development or sexual maturity rating are shown in and. Identify whether sexual maturation is advanced, normal, or retarded.

Puberty is considered delayed if no secondary sex characteristics (budding of breasts) are seen by 14 years in girls and 16 years in boys (increase in the volume of testes).

Precocious puberty is diagnosed in girls when breast development occurs before 8 years and menarche before 10 years of age and in boys when testicular enlargement occurs before 9 years of age.

Diagrammatic representation of stages of sexual maturity in boys 1 and girls 2 B1-B5, breast, G1-G5, male

genitals, PH1-PH5, pubic hair.

Assessment of Severity of Illness

It is important to assess whether an acutely sick child can be managed on an ambulatory basis or should be admitted to a hospital.

The presence of the following clinical features suggests that the child is critically sick

- Anxious, dull, and expressionless toxic look.

- Altered sensorium, moaning or groaning sounds, absence of cry, or inconsolable, shrieking and high-pitched cry, lack of any response to parental overtures, bulging anterior fontanel, or neck rigidity.

- Refusal to drink or eat.

- Abdominal distension or marked tenderness of the abdomen.

- Seizures without any past history of epilepsy or febrile convulsions.

- Hyperpyrexia (despite adequate antipyretic therapy and cold sponging) or hypothermia.Marked respiratory distress with intercostal recessions, grunting, and stridor or slow gasping breathing.

- Central cyanosis (in the absence of cyanotic heart disease), ashen-grey pallor, mottling of the skin, cold and clammy (wet) extremities, slow capillary refill, hypotension, and shock.

- Evidence of moderate to severe dehydration or acidosis (Kussmaul’s breathing), oliguria or

anuria (lack of urination for more than 6 hours in an infant and 12 hours in an older child). - Ecchymoses, petechiae, and bleeding manifestations.

Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE)

In order to eliminate subjectivity and cover a wide spectrum of skills for teaching and assessment of medical graduate and postgraduate students, OSCE has been introduced.

In a short period, the students can be taught or assessed for a large number of skills and use of tools.

Instead of the conventional long case and short case allocations for clinical examination, a number of clinical stations are created to assess a wide range of clinical skills of the students.

The station may have a live patient or vignettes of case scenarios, laboratory reports, and assessments of various skills and procedures.

Each station is allocated a time slot and the student is asked to do a task and record his or her observations on a pre-coded questionnaire.

Apart from the assessment of a wide range of skills and allocation of identical case material to all students, OSCE also eliminates the subjective bias of the examiners.

However, the creation of OSCE stations is time-consuming and labor-intensive for the examiners.

Depending upon the available clinical cases and skills to be tested, a wide range of OSCE stations can be created as mentioned in the following examples

- Assess the muscle tone of this one-year-old infant.

- Assess the developmental quotient of this girl with a corrected age of 18 months.

- Assess the vital signs including blood pressure in both the upper as well as lower limbs.

- Do the relevant physical examination of this child with a history of partial seizures on the right side.

- Do the examination of the heart of this 3-year-old boy.

- Record anthropometric measurements on this 6-month-old infant.

- Conduct an abdominal examination on this 5-year-old boy.

- Assess the primitive or automatic reflexes in this 2-week-old infant.

- Examine the chest of this 10-year-old boy with a history of fever and cough for one month.

- Examine the cranial nerves in this 5-year-old girl.

Leave a Reply