Spread Of Dentoalveolar Infection Introduction

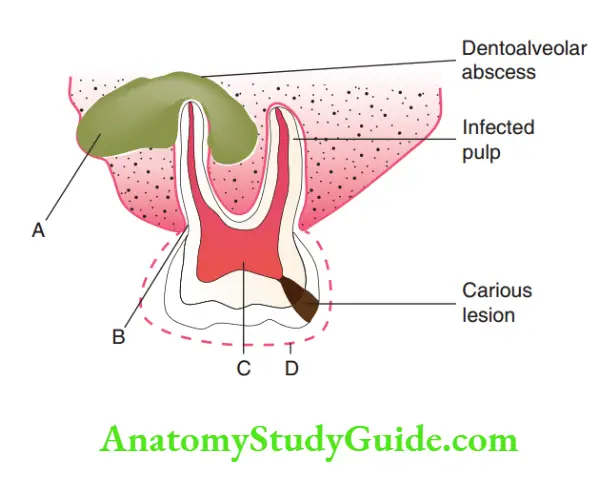

Dentalcariesinitiallyresultsininfectionofthepulp tissue.

Table of Contents

The micro-organisms spread through the apical foramen to involve the alveolar bone around the root tip(s).

This is termed ‘dentoalveolar infection’. This infection becomes an odontogenic septic focus with the potential to spread into the head and neck.

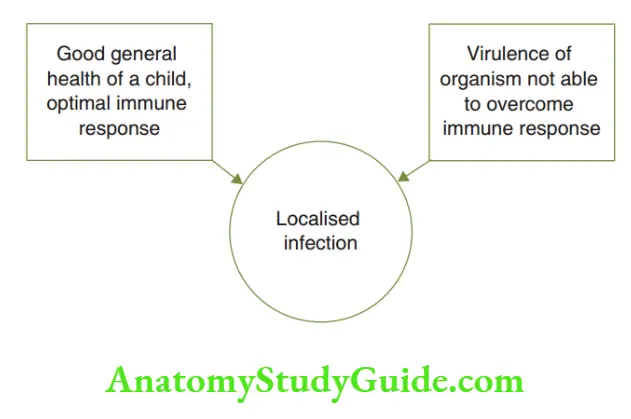

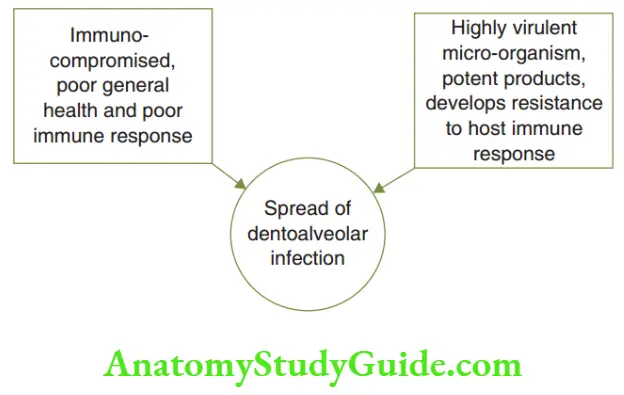

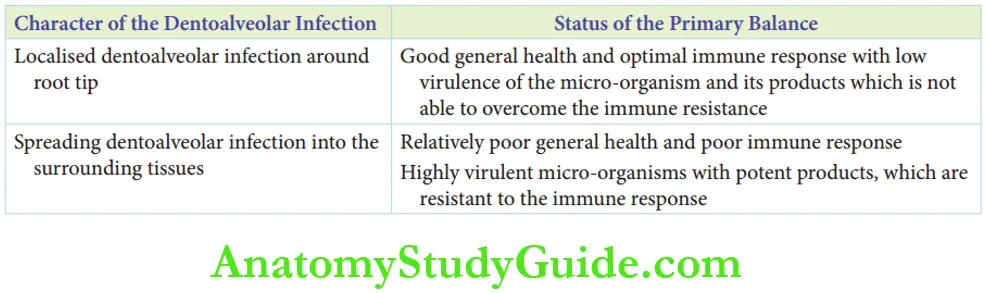

The chances of a dentoalveolar infection to be localised at the root tip or to spread into the surrounding tissues are based on a ‘primary balance’.

Read And Learn More: Paediatric Dentistry Notes

This balance is between the following two factors:

1. Patient: General health and immunity of the patient that resists the spread of infection.

2. Micro-organism: Virulence of the micro-organism and its products (endotoxins, zero toxins and lytic enzymes) and its immune resistance that augments the spread of the infection depict the chances of localised infection and those of spreading infection, respectively.

Phases Of Dentoalveolar Infection

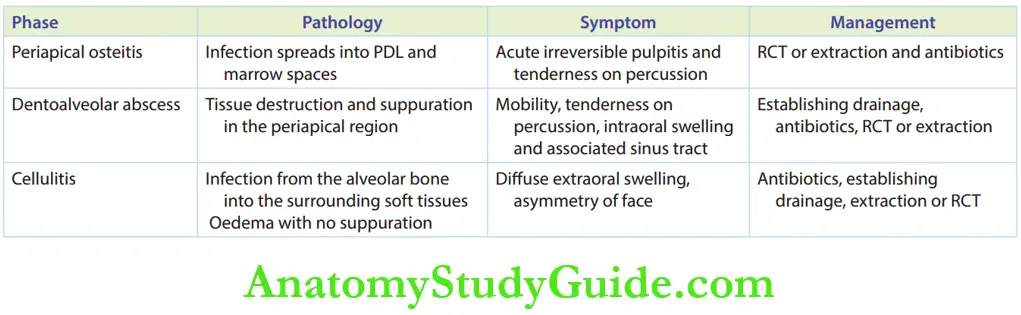

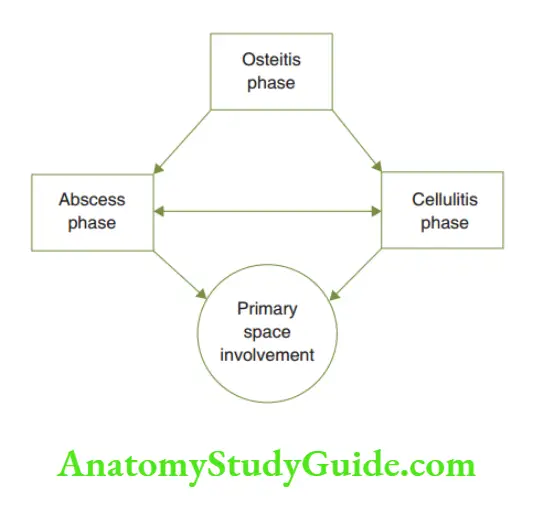

The dentoalveolar infection has three phases, where two phases can be coincidentally demonstrated.

With treatment, an acute dentoalveolar infection resolves.

However, when the acute nature subsides, it enters a chronic phase.

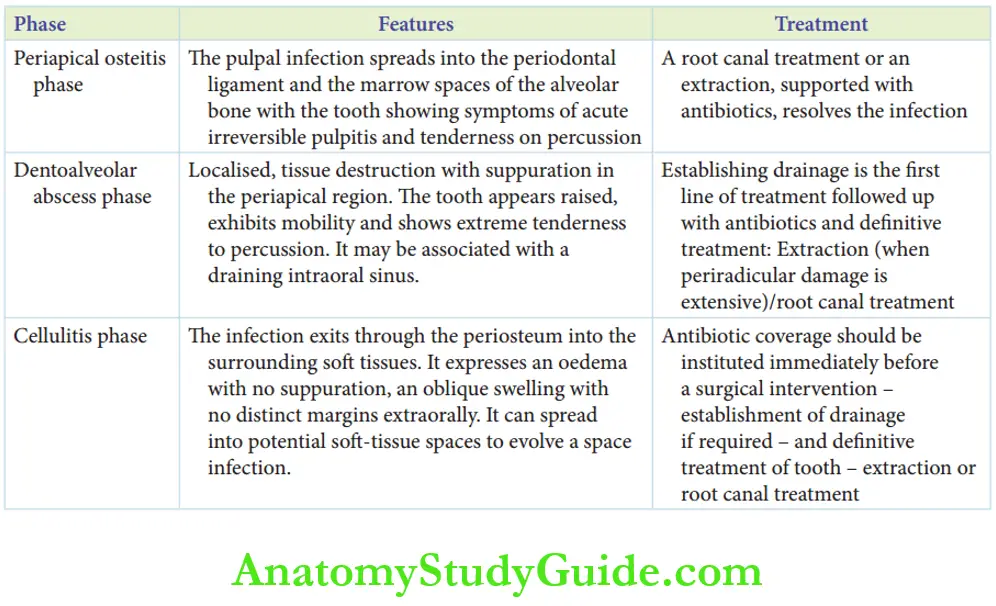

The three phases of acute dentoalveolar infection are as follows:

- Periapical osteitis phase

- Dentoalveolar abscess phase

- Cellulitis phase

Periapical Osteitis Phase

The pulpal infection spreads into the periodontal ligament and the marrow spaces of the alveolar bone.

The tooth shows symptoms of acute irreversible pulpitis.

They are spontaneous pain with little or no stimulation, pain on stimulation with hot foods/cold foods/physical stimulation and pain that lingers even when the stimulus is removed.

The tooth is highly tender on percussion.

A root canal treatment or an extraction, supported with antibiotics, resolves the infection.

Dentoalveolar Abscess Phase

With the spread of infection, localised tissue destruction with suppuration in the periapical region indicates this phase.

The tooth appears raised, exhibits mobility and shows extreme tenderness to percussion.

There may be an intraoral swelling around the involved tooth which may be associated with a draining intraoral sinus tract.

Establishing drainage is the first line of treatment.

Drainage may be established by one or more of the following methods:

The incision on the most pointing surface of the abscess:

1. A stab incision with a no. 11 blade followed by the application of dull pressure around the margins of the abscess to express the pus

2. Crevicular incision at the gingival sulcus on the side of involvement (buccal/lingual)

3. Opening of the pulp chamber (access opening)

4. Extraction of the involved tooth

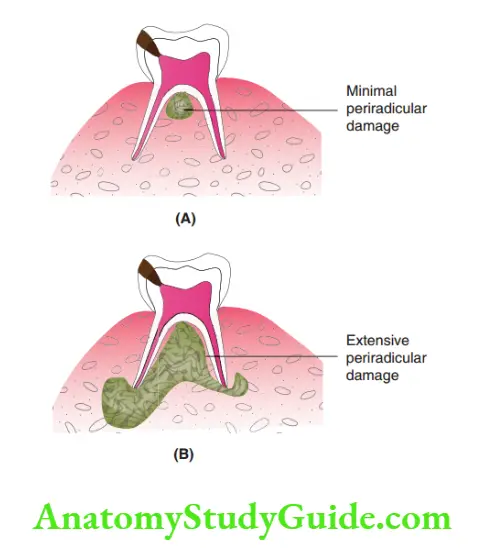

- When periradicular damage is limited, an optimal drainage can be established by the fist three modes. Root canal treatment is the definitive procedure of choice.

- When periradicular damage is extensive, extraction of the tooth is ideal.

Dentoalveolar Abscess Treatment

Antibiotic coverage before drainage of an abscess is contraindicated.

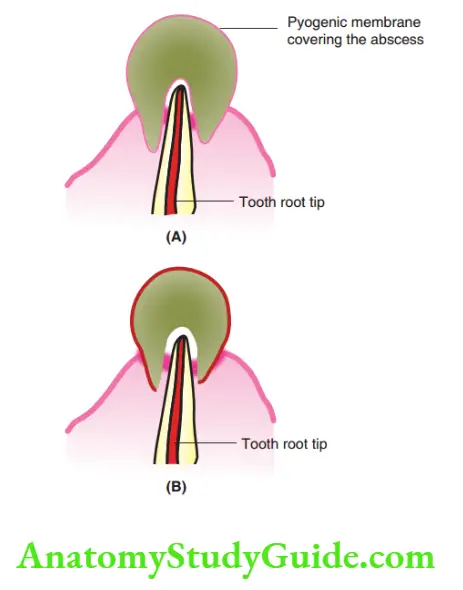

Any abscess contains protein exudates, necrotic debris, associated bacteria and acute inflammatory cells surrounded by a granulation tissue membrane called a ‘pyogenic membrane’.

The core of the abscess is devoid of blood supply. The pyogenic membrane does not allow antibiotics to be delivered to the core of the abscess.

In turn, the antibiotic incites a chronic inflammatory response at the membrane border.

With this, the abscess resolves into a chronic inflammatory mass.

This is called an ‘antibi-oma’ or ‘antibiotic-induced swelling’.

It becomes hard in consistent. Antibioma has to be treated by warm application for liquefaction of the lesion after removal of the dental focal sepsis.

Hence in case of a dentoalveolar abscess, drainage may be followed with antibiotics.

Definitive treatment (extraction/root canal treatment) for the tooth involved may be performed after the establishment of drainage in the same visit.

However, if root canal treatment is sought, access opening and biomechanical preparation are performed followed by an open/closed dressing.

Obturation may be done aftr 24 hours. The 24-hour Lee way period is to permit the drainage of pus/oedema fluid, if any.

Cellulitis Phase

The infection from the alveolar bone exits through the periosteum into the surrounding soft tissues.

It expresses oedema with no suppuration and an oblique swelling with no distinct margins.

This diffuse swelling exhibits extra orally to present an asymmetry

of the face.

The infection spreads through potential spaces within the soft tissues, which when involved is called a ‘space infection’.

Cellulitis describes a spreading infection where the virulence of micro-organisms is substantially stronger to outwit the host’s immune resistance.

Any therapeutic intervention can induce bacteraemia, thus increasing the rate of spread of infection.

Hence, antibiotic coverage should be instituted immediately before a surgical/operative intervention of the tooth, that is extraction or access opening and biomechanical preparation.

Cellulitis Treatment

The antibiotic coverage can be 50 mg/kg body weight amoxicillin with 10 mg/kg body weight metronidazole, 1 hour before the procedure.

Postoperative antibiotics, that is, amoxicillin 20–40 mg/kg body weight in three divided doses and metronidazole 5 mg/kg body weight thrice a day, have to be prescribed.

Cellulitis is also associated with an increase in body temperature due to bacteraemia arising from a dental infection.

Paracetamol 5 mg/kg body weight four to six times a day is also required.

The antibiotic coverage is followed by an establishment of drainage of the space involved (if required) and later definitive therapy of the tooth involved:

1. Extraction: When the infection does not resolve or extensive periradicular damage exists.

2. Root canal treatment: When periradicular damage is limited with the spreading infection promptly responding to antibiotics.

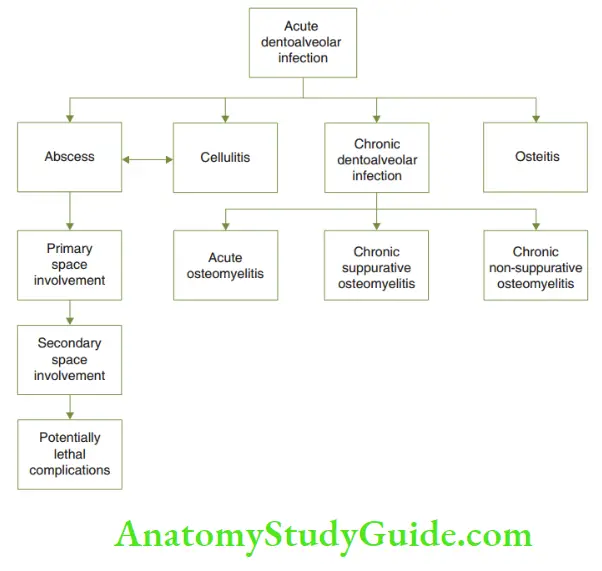

shows the association between an abscess, cellulitis and space involvement in dentoalveolar infection.

The space involvement is discussed in the subsequent sections of the chapter.

Local Spread Of Dentoalveolar Infection

An untreated dentoalveolar infection expands and extends into the surrounding adnexa.

The dentoalveolar infection perforates the alveolar bone to reach the soft tissue.

From the soft tissue, the infection can spread into the potential facial spaces or may be localised submucosally.

Localised submucosal spread may more commonly point intraorally than on the extraoral aspect.

Also, the infection culminates on the buccal (labial) side than on the palatal (lingual) side.

Facial spaces are potential spaces between planes of facial muscles.

These spaces are deflated in the absence of infection. With the infection spreading, the oedema fluid expressed inflates these potential spaces.

This infectious involvement of facial tissue spaces is called a ‘space infection’.

The various facial spaces involved in children are buccal space and submandibular space.

Canine space and submental spaces are less commonly involved.

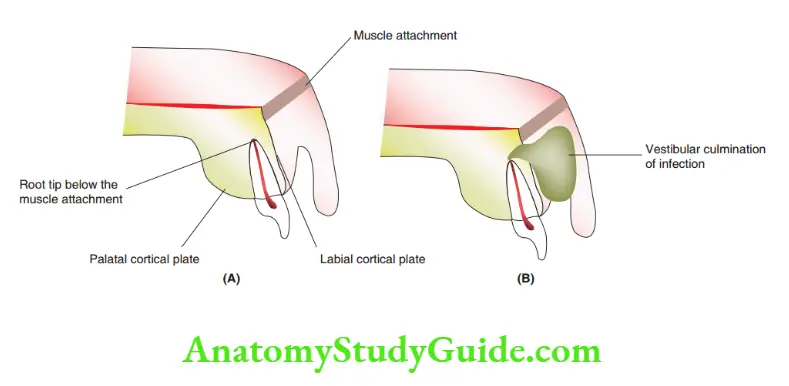

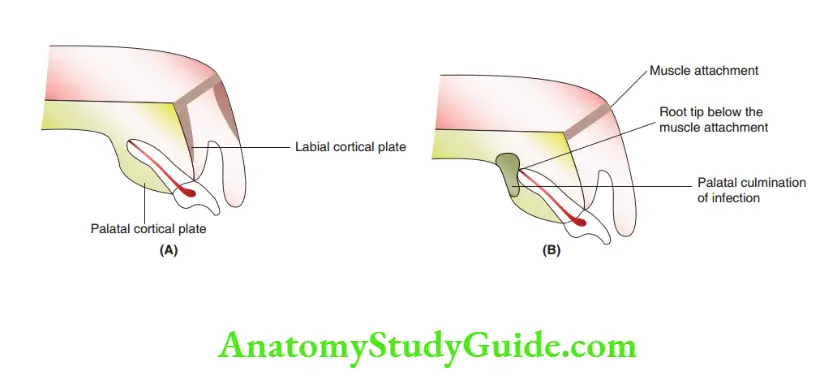

The parameter that decides if a dentoalveolar infection spreads into soft tissue submucosally or into tissue spaces is the relation between the tooth root tip and the corresponding muscle attachment.

If the root tip of the tooth is placed beyond the adnexal muscle attachment, a space infection ensues.

If the root tip is below the muscle attachment, local submucosal foci evolve.

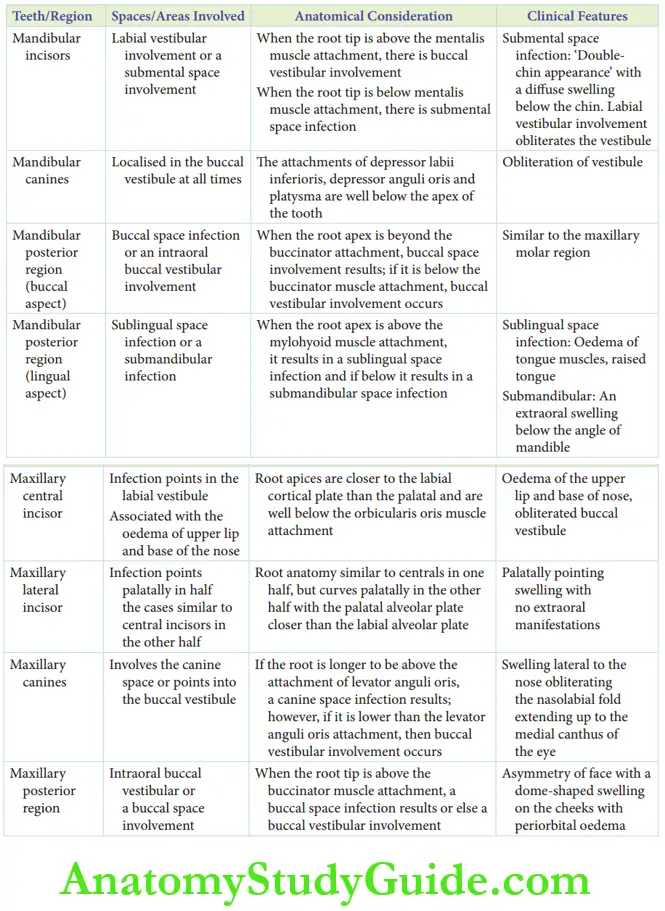

Anterior Maxillary Region

The spread of infection from the central incisor, lateral incisor and canine is discussed under this region.

1. Central incisor: the spread of infection from the maxillary central incisor.

Anatomic Consideration

- The root apex of permanent and primary incisors is closer to the labial cortical plate than the palatal cortical plate.

- The apices are well below the orbicularis oris muscle attachment. The orbicular oris muscle and the dense subcutaneous tissue at the base of the nose contain the infection.

- Hence, the spread of infection is below the muscle attachment pointing into the labial vestibule.

Clinical Features

The labial vestibule is obliterated.

Diffuse oedema of the upper lip and the base of the nose are distinctively noted.

Lateral incisor: the spread of infection from the maxillary lateral incisor.

Anatomic Considerations

The root anatomy of one-half of the lateral incisor is identical to that of the central incisor in anatomical placement.

The other half has a curved root apex with the palatal alveolar plate closer than the labial alveolar plate.

Hence, Aden to alveolar infection may point palatally.

Clinical Features

The infection seems to be a swelling pointing into the palate with no extraoral manifestations.

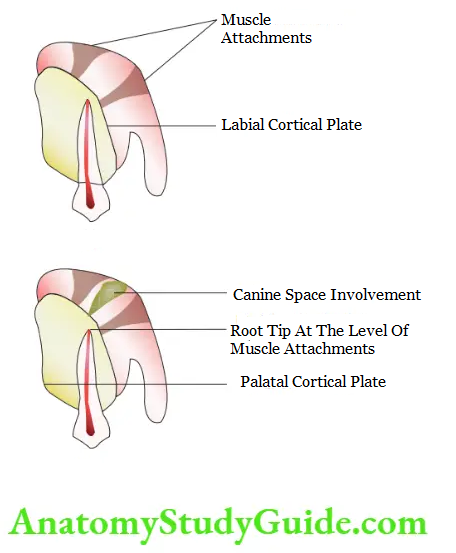

3. Canines: the spread of infection from the maxillary canine.

Anatomic Considerations

The primary maxillary canine tip lies closer to the buccal alveolar bone than the palatal alveolar bone.

The tip of the permanent canines lies above the attachment of the levatoranguliorismuscle.

The potential space located here is roofed by the canine space.

Attachment of muscles – levator anguli oris and levator labii superioris on the anterior maxilla – forms the base of the canine space.

If the root tip is longer and situated higher than the attachment of the levator anguli oris muscle, the canine space will be involved in the spread of dentoalveolar infection.

If the root tip is lower than the levator anguli oris muscle attachment, an intraoral buccal vestibular involvement would occur.

Clinical Feature

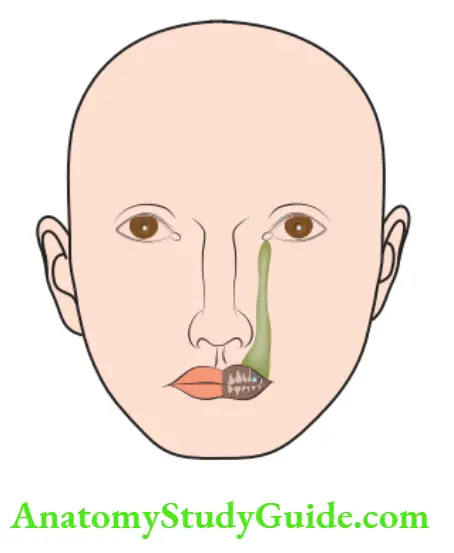

Canine space involvement is characterised by a swelling lateral to the nose obit eating the nasolabial fold extending up to the medial canthus of the eye.

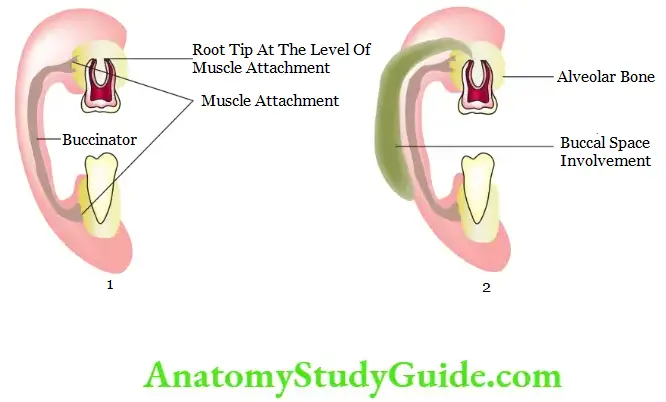

Posterior Maxillary Region

The spread of infection from the maxillary molar.

Infection from the maxillary primary and permanent molars can present either as an intraoral buccal vestibular involvement or as an extraoral, periorbital, dome-shaped buccal space involvement.

Anatomic Consideration

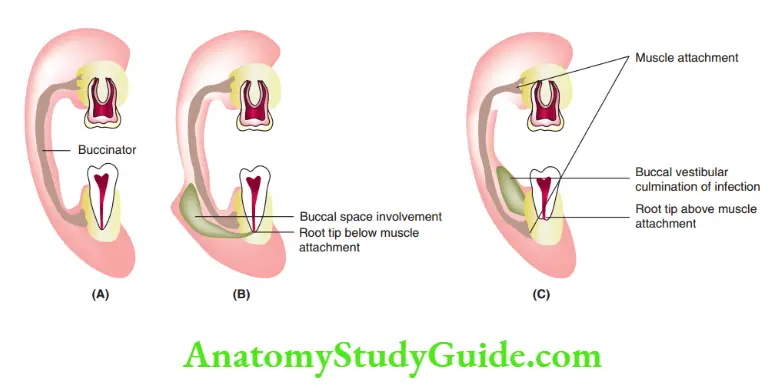

The key anatomic consideration is the attachment of the buccinator muscle.

The buccinator muscle with its buccopharyn goal fascia is the medial relation of the potential buccal space.

The buccal space is bounded laterally by the skin and tissues, superiorly by the zygomatic arch and inferiorly by the lower border of the mandible.

Hence if the root tip is below the attachment of the buccinator muscle, intraoral buccal vestibular swelling results.

If the root tip is above the buccinator muscle attachment, it results in a buccal space involvement.

A buccal space involvement can extend to the lower border of the mandible.

The facial asymmetry can be exuberant owing to the diffuse oedematous involvement of the adjacent tissues.

Clinical Features

- Buccal space involvement exhibits a dome-shaped swelling on the cheeks with periorbital oedema.

- Intraoral buccal vestibular involvement shows vestibular obliteration, rarely with a facial asymmetry. Facial asymmetry is demonstrated only when the abscess is excessively large.

Mandibular Anterior Region

The spread of infection from mandibular incisors and mandibular canines is discussed here.

1. Mandibular incisors: The spread of infection from mandibular incisors.

Anatomic Considerations

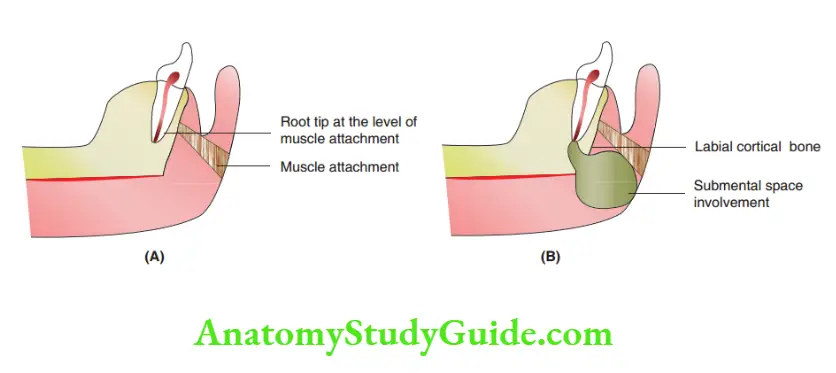

The key consideration is the attachment of the mental muscle.

- If the root tip is above the attachment of the mentalis muscle, an intraoral buccal vestibular involvement results.

- If the root tip is below the mentalis attachment, on perforation of the labial bony periosteum, the infection involves the unpaired, median submental space. This space is bounded by the skin and fascia inferiorly, mylohyoid superiorly and the anterior belly of digastric laterally.

Mandibular Anterior Region Clinical Features

When the submental space is involved, the child has a ‘double-chin appearance’ with a diffuse swelling below the chin.

Labial/buccal vestibular involvement obliterates the vestibule and has no obvious extraoral manifestations unless the intraoral vestibular swelling is ‘excessively large’.

2. Mandibular canine: The spread of infection from the mandibular canine The spread of infection from the canines will, in all circumstances, localise in the buccal vestibule, as the attachments of depressor labii inferiors, depressor anguli oris and platysma are well below the apex of the tooth.

Clinical Features

Obliteration of the labial vestibule with no extraoral manifestation is the clinical presentation.

However, when the intraoral vestibular swelling is excessively large, it results in facial asymmetry.

Mandibular Posterior Region

The spread of infection from mandibular molars buccally and lingually, respectively.

The buccal and lingual aspects are discussed separately.

Anatomic Consideration Of The Buccal Aspect

The key anatomic consideration is the level of attachment of the buccinator muscle in relation to the root apices of the primary molars.

If the root apex

Extends beyond the attachment of the buccinator, a buccal space involvement results

Extends below the buccinator attachment, an intraoral buccal vestibular swelling results

Clinical Features Of The Buccal Aspect

- Buccal space involvement exhibits a dome-shaped swelling on the cheeks with periorbital oedema similar to that with maxillary teeth.

- Intraoral buccal vestibular involvement shows vestibular obliteration, rarely with a facial asymmetry (when excessively large).

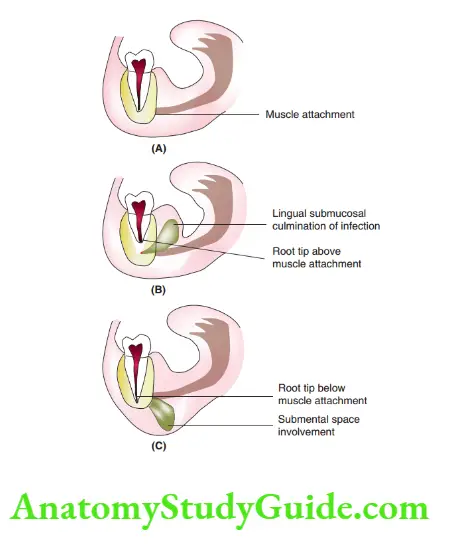

Anatomic Consideration Of The Lingual Aspect

The key anatomic consideration is the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle.

If the root apices are

Above the attachment of mylohyoid, it results in a sublingual space infection

Below the attachment of mylohyoid, it results in a submandibular space infection

Clinical Features Of The Lingual Aspect

Sublingual and submandibular space infections are discussed next.

Sublingual Space Infection

The sublingual space is a potential space on the floor of the mouth below the tongue.

It is bounded by the mylohyoid muscle at its floor and by the oral mucosa at its roof, laterally and anteriorly by the mandible, medially by the muscles of the tongue and posteriorly by the body of the hyoid.

When the sublingual space is involved, the oedema is interspersed into the intrinsic muscles of the tongue and spreads to the opposite side.

The tongue is raised from the floor of the mouth.

Submandibular Space Infection

The submandibular space is bounded by the mylohyoid as its roof and skin and cervical fascia as its floor.

Spaceinfection presents as an extraoral swelling below the angle of the mandible.

Sublingual space and submandibular space communicate along the posterior border of the mylohyoid.

When primary space infection is not treated, it can proceed to a serious bilateral involvement of submandibular, sublingual and submental spaces.

This condition is termed Ludwig’s angina.

Sequelae Of Acute Dentoalveolar Infection

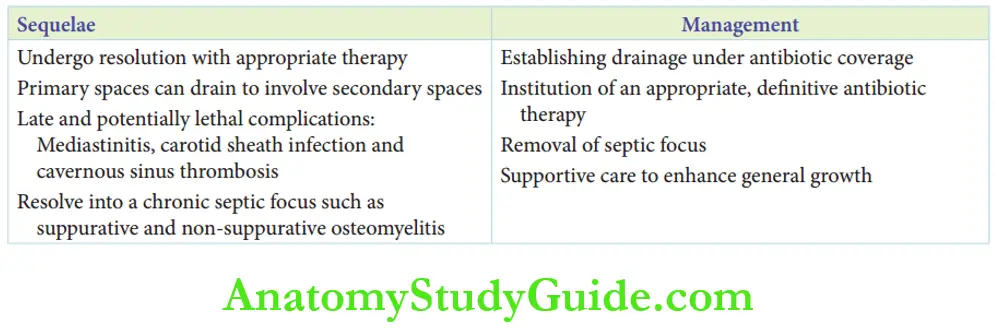

Acute dentoalveolar infection can undergo resolution with appropriate management.

Acute dentoalveolar infection extending into primary spaces as a space infection can have serious consequences if untreated.

The following consequences may result in the absence of appropriate and timely treatment:

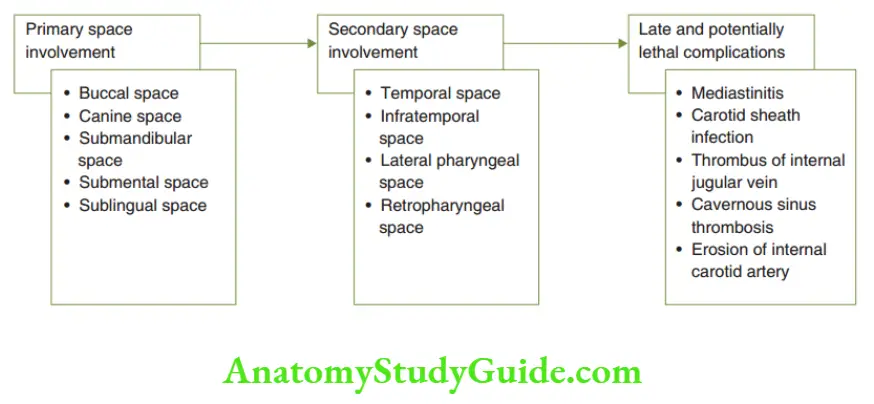

1. Primary space infections (buccal space, submental space, sublingual space, submandibular space and canine space) can subsequently involve secondary spaces such as temporal space, infratemporal space, lateral pharyngeal space and retropharyngeal space.

2. Mediastinitis, carotid sheath infection and cavernous sinus thrombosis are late and potentially lethal complications of secondary space involvement.

3. Acute dentoalveolar infection can turn into a dormant focus. It then transforms into a chronic septic focus.

The common types of chronic dentoalveolar infection are as follows:

- Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis: It is a suppurating type of destruction of the cortical and cancellous bone associated with an extraoral draining sinus. The treatment involves removal of the offending tooth, removal of the necrotic bone (sequestrum) and curettage.

- Chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis with proliferative periostitis (Garre’s osteomyelitis):

- When the virulence of the micro-organism is subdued by the exuberant host immunity, persisting low-magnitude infective focus can result in sclerosis of the cancellous bone and expansion of the cortical plate.

- Garre’s osteomyelitis requires the removal of the septic focus and curettage.

Surgical recontouring is usually not required as the buccal expansion can return to normal with an ongoing growth-resuming function.

Treatment

The treatment outline for the management of spreading dentoalveolar infection is as follows:

- Establishing drainage under antibiotic coverage

- Institution of an appropriate definitive antibiotic therapy

- Removal of the septic focus

- Supportive care to enhance general growth

Trismus And Facial Space Involvement In Children

Trismus is rarely encountered in facial space involvement in children. The primary space infections that manifest trismus are pterygomandibular space infection and submassetric space infection.

The roots of primary molar and fist permanent molars can very rarely reach into these spaces. Hence, trismus is rare.

Summary

1. Dentoalveolar infection may be localised or spreading in character based on a primary balance

2. Three phases of acute dentoalveolar infection are as follows:

3. Spread of dentoalveolar infection from different regions

4. Sequelae/management of spreading acute dentoalveolar infection

Leave a Reply