The Art Science Pediatric Diagnosis

The ideal pediatrician must have a genuine interest in and love for children. The opportunity of nurturing one’s own children or grandchildren is a great learning experience for a pediatrician.

Table of Contents

He must be humane, systematic in his approach, and genuinely interested in the welfare of his patients. He should exude confidence, patience, and politeness to elicit the cooperation of patients and his attendants.

These qualities are crucial to generate the faith of parents in their capabilities, which is a great healing force. The physician who exhibits evidence of hurry, worry, and indecision is unlikely to inspire any confidence in his patients.

Read and Learn More Pediatric Clinical Methods Notes

To augment the process of healing, the patient must have faith in his doctor and a doctor must have faith in himself and his medicines.

The pediatrician should approach children as children (not patients) with tact, gentleness, warmth, and genuine concern.

He should have a sober and affectionate look so that children are not afraid of him. Unlike adults, children distrust the man who looks into their eyes.

He must have a scientific bent of mind, and use logical systematic steps to arrive at a diagnosis with the help of core knowledge and basic principles.

He should not be dogmatic and should be aware of the limitations of his own knowledge and of knowledge in general and should never hesitate to say that “I don’t know”.

He is a perpetual student, constantly learning and unlearning to transform knowledge into wisdom. The attributes of a pediatrician are

The Attributes of a Pediatrician

- Good physical and mental health

- Knowledge and skills

- Wisdom

- Confidence

- Patience

- Politeness

- Humility

- Common sense

- Pleasant demeanor or bedside manners

- Experience and expertise

- Tact

- Compassion

- A kind and affectionate look

- Love for children

- Intuition

- Healing touch

listed in The welfare of the patient must be considered as supreme and should take precedence over all other considerations including his personal pride or commercial gain.

Nevertheless, he should not underestimate his own ability to make new and original observations.

Above all, though medicine is a profession but life should never be weighed in gold it is too precious! According to Mother Teresa, medicine must be viewed as a mission and it should not be downgraded as a profession or business.

Children are afraid of hospitals, doctors, and needles and they should never be blackmailed through threats of injections to modify their behavior.

It is controversial whether pediatricians should wear white coats or not although it appears immaterial to me. The white coat does complement the professional attitude and inculcates a sense of discipline and decorum.

The pediatrician must conduct himself with dignity, seriousness, and respect toward parents regardless of how deviant their behavior may appear at times of distress.

He should establish a warm and cordial interpersonal relationship with his team members by virtue of the qualities of his head and heart. He must demonstrate impeccable bedside manners and serve as a role model to his students.

He should not merely be a healer but truly serve as a philosopher and guide to his patients parents and students.

The Approach To Physical Diagnosis

The methods of physicians are like those of a detective, one seeking to explain the disease, the other a crime. There are no shortcuts for making a physical diagnosis.

It is learned only by practice, not a dull, dreary monotonous practice but practice with all the five senses alert.

The astute physician is endowed with sharp and sensitive special senses (especially keen observation) and must harness the skills of a lawyer, detective, and judge.

During the last two decades, a revolution in imaging technology by the introduction of ultrasound, CT scanning, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography has eroded the confidence and enthusiasm of clinicians.

It is a sad reality that physicians are becoming more technocrats and losing the art of medicine.

The patient is being fragmented into systems, organs, tissues, cells, and even DNA! It is crucial that we should not lose sight of the totality of the patient and his interactions with the social and ecological milieu.

Instead of causing disuse atrophy of clinical judgment, the newer technology should be fully exploited and harnessed to improve clinical judgment and enhance the understanding of pathogenetic mechanisms underlying the disease process.

The correct diagnosis of the underlying disorder and its probable etiology is crucial for rational management and prognostication.

The diagnosis is based on the elicitation of correct evidence and its analysis and interpretation of findings and observations in the light of the core knowledge, wisdom, and experience of the pediatrician

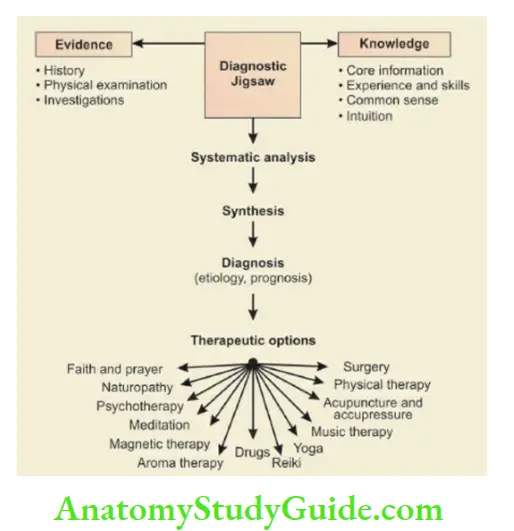

The key elements to solve the diagnostic puzzle. The correct diagnosis is crucial to institute rational therapy.

The Evidence

Just as evidence is crucial for a detective to identify the culprit, similarly sound evidence collected by history, physical examination, and investigations is of fundamental importance to solve the diagnostic dilemma.

History

Good history-taking is an art and it needs inquisitiveness, persistence, and tact. You must emphasize the important, minimize the unimportant and suppress irrelevant information.

The history should be sifted off undue parental anxiety and concern in order to obtain a lucid chronological story with special emphasis on the onset and evolution of the disease process.

Through a process of a detailed review of various symptoms and systems, an attempt should be made to identify the organ(s) affected by the disease process.

Identify whether a single system is affected or you are dealing with a multisystem disorder. Attempts should be made to identify whether a disorder is acute, subacute, chronic, or insidious and classify it into static, resolving, or progressive in nature.

The psychological, social, ethnic, geographical, ecological, and genetic factors influencing the disease process should be identified.

Sir William Osler rightly said, “Medicine is about sick people, not about diseases”. Race and ethnicity play an important role in the expression of disease.

In addition to genetic factors, individuals with similar ethnic backgrounds share cultural, nutritional, environmental, economic, and social characteristics that influence the disease.

An experienced pediatrician is able to emphasize the important, minimize the unimportant, and suppress irrelevant information in history.

It must be remembered that over 75% of diagnoses can be correctly made by virtue of good history alone.

It is important that no observation of the mother, whether apparently trivial or unimportant, should be ignored or set aside if it fails to fit into the tentative diagnosis.

Indeed, it may be the most important clue or hint to unravel the diagnostic puzzle.

The history tells of events that have led to the present condition of the patient while examination reveals the status of the patient at a given moment.

Accuracy of history depends upon the education, memory, intelligence, and concern of the attendant while the yield of the physical examination depends upon the experience, skills, and thoroughness of the pediatrician.

Most errors in medicine are made by making cursory incomplete examinations and not due to a lack of knowledge and skills. The approach during the examination should be both humane and systematic.

The pediatrician must have inherent fondness and love for children and examine them with warm hands and a warm heart. The examination chamber should be warm, familiar, well-lighted, and stocked with soft toys.

Deep yellow- or blue-colored curtains should be avoided in the examination chamber because they may interfere with the interpretation of jaundice and cyanosis.

The children must be treated as children and not patients and examination should be conducted in an unstructured playful manner. Patients must be handled with utmost care and reverence as they are the real books of physicians.

The maximum time should be devoted to the observation of the child and to the system or organ which appears to be predominantly affected on the basis of history.

Physicians must sharpen their observation skills by enhancing the capabilities of their special senses. Pediatrics deals with children from birth to adolescence, varying in size from less than 1.0 kg to over 50 kg and having different grades of functional maturation of various organs.

Pediatrics has been likened to a flying bird that deals with the dynamic, evolving, and changing size and maturity of children.

The knowledge regarding developmental anatomy, developmental pharmacology, developmental biochemistry, and developmental biology, in general, is crucial for the proper evaluation of normal children at different ages for appreciation of abnormalities or deviations due to diseases.

You must have information regarding normal variations at different ages before you can pick up the abnormalities.

The developmental or functional status of the child affects the incidence and expression of various diseases and conversely, diseases may adversely affect the growth and development of children.

The lymphoid tissue is physiologically hypertrophied in children leading to the development of large tonsils or cervical lymphadenopathy following minor infections.

The Role of Laboratory Investigations in Pediatric Diagnosis and Management

They are useful to assess the degree of organ dysfunction, assist in confirming the diagnosis, and help in management, prognostication, and follow-up.

There is no justification to undertake routine investigations on every patient. Instead, appropriate and relevant investigations should be ordered depending on the diagnostic possibilities entertained on the basis of a detailed clinical evaluation.

The pediatrician should be aware of the limitations of all laboratory tests and follow the philosophy that the laboratory should be used as a slave and not a savior.

You must have faith in your clinical acumen and use the laboratory as an aid for confirmation of the diagnosis in order to provide effective and rational management to the patient.

The approach should be to treat the patient and not his laboratory reports. Nevertheless, the diagnosis should not be delayed by postponing essential investigations.

Timely laparotomy may be life-saving in a child with an acute abdomen, undiagnosed lump, and for differentiation between neonatal hepatitis and extrahepatic biliary atresia.

Children with cervical lymphadenitis should not be given a trial of antitubercular therapy unless the diagnosis is confirmed by fine needle aspiration cytology or lymph node biopsy.

The Pediatrician Core Knowledge

The evidence generated by painstaking history, physical examination, and investigations should be viewed in the light of the available knowledge and experience of the pediatrician.

Every pediatrician should be aware of the essential features and criteria of common childhood disorders. It must be remembered that no symptom or sign has 100% frequency or specificity in a disorder because no two patients are alike.

In general, the manifestations of diseases are rather atypical among neonates and infants.

You must have up-to-date knowledge pertaining to the current state-of-the-art for the diagnosis and management of common pediatric problems otherwise you will get rusted and outmoded.

A large number of diseases in children can be diagnosed on the basis of typical facies or facial dysmorphism. The physician must be equipped with some core knowledge because chance favors only the prepared mind.

It is well known that what the mind knows, is more likely to explore and discover in the patient.

The diagnosis of acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis can only be made, if one knows that it is characterized by acute onset of puffiness and edema feet, oliguria, and smoky urine (microscopic hematuria), hypertension and azotemia following two weeks later after the inadequately treated attack of acute streptococcal pharyngitis.

The Physicians’ Art Of Diagnosis

The diagnostic process is one of the greatest challenges in medicine. The patient should be viewed as a jigsaw puzzle and you should be patient, relaxed, and methodical to solve the dilemma.

The evidence (demography, epidemiology, symptoms, signs, investigations) pertaining to the patient should be sifted and analyzed through a process of logical thinking in the light of core knowledge, experience, and clinical judgment of the pediatrician to arrive at plausible diagnostic possibilities.

All the points in favor and against a particular diagnosis should be carefully weighed to arrive at a final diagnosis.

The physician should have a thorough understanding of basic principles to solve the diagnostic puzzle and be aware of the limitations of his own knowledge to avoid dogmatism.

There is no place for expressions, such as NEVER and ALWAYS in medicine. The greater the ignorance, the greater is the dogmatism. Be humble and don’t have a “know all” attitude.

It is wiser to confess ignorance than to “beat about the bush” or give silly explanations. We must keep in mind that our knowledge in matters of health and disease is like a pond while our ignorance is Atlantic.

The following principles are useful to keep in mind while making a diagnosis

- The psychogenic label is the commonest refuge of the diagnostically destitute. The functional disorder should be diagnosed both by the exclusion of an organic disorder and by the presence of positive evidence of a psychogenic disturbance.

Attention must be paid to the whole child along with his environment rather than merely to his body organs. The focus should be on the child and not his disease. Ask the mother how the index child differs or compares with other siblings.

The behavior and personality disorder in a child is a reflection of parental discord and the child should be considered as a barometer of the family’s emotional health.

The psychological symptoms in a child are a signal to implore us, “Please help my family.” - Remember the stark reality that common diseases occur more commonly. The rare manifestations of a common disorder are more common than the common manifestations of a rare disorder.

When a symptom or a sign is commonly found in a large number of diseases, its absence is more significant than its presence for making a specific diagnosis. - Give due credence to the diagnosis made by the previous physician but do not accept it as gospel truth.

You should make your own decision regarding the likely diagnosis based on the sequence of events, course of the disease, leads obtained on investigations, and response to medications. - Efforts should be made to fit the total clinical picture into a single diagnostic entity.

This is more often possible in a child as compared to an adult.No diagnosis should be taken for granted, even when it is attributed to a reliable physician or a renowned medical institution unless it is based on sound evidence and logic. - Avoid masking symptoms and signs by giving drugs to a patient with an evolving disease process.

Do not instill mydriatics into the eyes for examination of the fundus or give sedatives to a child with a head injury because this would compromise the diagnostic utility of pupillary size and level of consciousness.

In the case of undiagnosed acute abdomen or head injury, strong analgesics and sedatives should be avoided. - Do not delay the surgical diagnostic procedure or a laparotomy whenever it is indicated.

- The diagnosis of a curable disease should not be overlooked. When the clinical picture is compatible both with tuberculosis and Hodgkin’s disease, it is preferable to confirm the diagnosis by lymph node biopsy before starting treatment.

- Do not allow the social position of the patient or family to limit your examination. Undress the child completely whenever necessary. Incomplete or cursory examination is the most important cause of diagnostic misadventures.

- Be confident but don’t be biased or dogmatic in your approach. Be humble and considerate.

- The diagnosis may be made in stages and don’t hesitate to revise your diagnosis after a period of observation. The appearance of new symptoms and signs, as the disease evolves, may offer additional diagnostic clues.

Sir Robert Hutchison, the legendary clinician, has enunciated several don’ts for diagnosticians.

The Diagnostic Possibilities

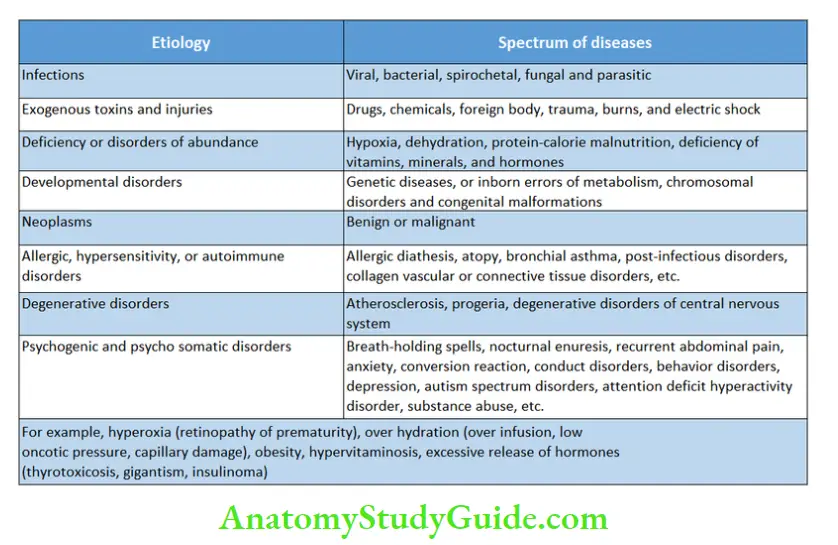

In the allopathic system of medicine, most diseases can be classified into eight broad etiologic groups. Infections account for over 75% of all diseases.

In children, protein-calorie malnutrition and deficiency of micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) constitute the core health problem that makes children susceptible to developing infective disorders which are likely to run a relatively fulminant course.

Overnutrition and obesity are emerging as public health problems among adolescent children belonging to affluent or well-to-do families. Most genetic (inborn errors of metabolism), chromosomal and developmental abnormalities manifest during childhood.

Degenerative disorders due to aging are uncommon in children but there is a need to identify various clinical and laboratory markers for these disorders so that preventive strategies can be instituted during childhood to reduce the burden of these diseases during adult life.

We must remember that seeds of most adult diseases, like obesity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease, are sown in childhood.

After clinical assessment, a tentative diagnosis should be made and various differential diagnostic possibilities in the order of their probability should be listed before ordering investigations.

It is essential to make a complete diagnosis including the primary condition and likely cause, associated complications, like intercurrent infections, and concomitant disorders.

- Don’ts for diagnosticians

- Don’t be too clever

- Don’t diagnose rarities

- Don’t be in a hurry

- Don’t be faddy

- Don’t mistake a label for a diagnosis

- Don’t diagnose two diseases simultaneously

- Don’t be too cocksure

- Don’t be biased

- Don’t hesitate to revise your diagnosis

- Don’t be dogmatic

- Don’t be arrogant

- Don’t ignore your intuition and common sense

For example; protein-calorie malnutrition, marasmic type, faulty feeding and weaning practices, recurrent diarrhea, hypothermia, nutritional anemia, zinc deficiency, primary pulmonary complex, and scabies.

In systemic disorders, the clinical diagnosis should indicate the site of disease (anatomy), physiologic basis, pathology, etiology, predisposing or risk factors, complications, and associated disorders.

Examples of clinical diagnoses in various systemic disorders are given below.

Alimentary System and Abdomen

- A case of cirrhosis (pathology) following viral hepatitis (etiology) with portal hypertension, anemia, hepatocellular failure, hematemesis (complications), and a history of blood transfusion at the age of 3 years (risk factor).

- A case of failure to thrive with recurrent episodes of diarrhea (malabsorption) due to celiac disease (pathology) with iron deficiency anemia, rickets, and rectal prolapse (complications).

Respiratory System

- A case of right upper lobe (anatomy) consolidation (pathology) is probably due to bacterial pneumonia (etiology) with empyema (complication) following pyoderma and protein-energy malnutrition (risk factors).

- A case of left-sided (anatomy) pleural effusion (pathology) probably of tuberculous origin (etiology) with history of primary pulmonary complex at 2 years of age (risk factor).

Cardiovascular System

- A case of mitral (anatomy) stenosis (physiology) of rheumatic origin (etiology) without any congestive heart failure or rheumatic activity and the patient is in sinus rhythm at present.

- A case of mitral stenosis and aortic (anatomy) incompetence (physiology) of rheumatic origin (etiology) with bacterial endocarditis, cardiac failure, and atrial fibrillations (complications).

Central Nervous System

- A case of spastic paraparesis in extension (deficit or physiology) due to compressive myelopathy caused by caries spine (etiology) and the lesion is at the level of T10 segment of the spinal cord (anatomy or site of lesion) with urinary retention and urinary tract infection (complications).

- A case of left-sided complete hemiplegia (deficit or physiology) due to cerebral thrombosis involving the lenticostrie branch of the middle cerebral artery (etiology) and the site of lesion is in the right internal capsule (anatomy or site of lesion) with protein-energy malnutrition and impetigo (associated conditions).

The Rational Management

The purpose of making a correct diagnosis is to institute rational therapy and provide prognostic guidelines to the family.

It is preferable to use a single most appropriate therapeutic agent, which should be administered in an optimal dose through the most convenient route, instead of instituting a “shotgun” therapy with half a dozen drugs.

It is desirable to use familiar drugs which have withstood the test of time. The newer drugs or procedures are not necessarily better.

The discomfort and pain of the patient must be relieved by appropriate and safe medicines with due regard for their comfort and well-being. We must provide global care to the child rather than a mere cure for a disease process.

Complete and comprehensive advice regarding diet, personal hygiene, and immunizations should be given to all children irrespective of the underlying disease process.

Medical systems should not be fragmented into watertight compartments and instead, all systems including complementary and alternative systems (CAS) should be exploited and harnessed to provide relief.

The government of India has introduced the concept of AYUSH by providing a kit to primary health care providers, which contains Ayurvedic, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathic medicines, apart from medicines belonging to the modern or Allopathic system.

However, it is illogical to treat a patient simultaneously with homeopathic as well as allopathic medicines because one is supposed to express the disease and the other tries to suppress it.

The physician must establish a rapport with the child and his parents to provide them with emotional support and win their confidence.

The pediatrician who is likely to exhibit evidence of hurry, worry, and indecision is unlikely to inspire confidence in his patients.

The skillful physician knows when to sedate with drugs when to soothe with words, when to treat aggressively for cure, palliatively for relief, and consolingly for comfort.

What we don’t say and what we do say, how we say it, and when we say it, makes all the difference between helping and not helping our patients.

These attributes and skills cannot be learned from books but by emulating the example of one’s model teachers who are of course a dwindling tribe in the modern commercialized society.

The patients and attendants have emotional feelings and one should avoid saying “Nothing can be done” (because something can always be done), “There is nothing wrong” (even when it is a functional disorder), “Don’t worry”, “it is all right”, etc.

The world needs caring and concerned physicians, and not merely curing and commercial robots who lack compassion and deny healing virtues of the human touch. Identify the major worries and fears of the child and his parents.

Relieve their anxiety, reassure them, and restore their confidence so that the will to fight is never dulled or extinguished. Nevertheless, be honest and pragmatic with your patients.

There is hardly any place for the use of injections in ambulatory pediatric practice except for the administration of vaccines and treatment of anaphylactoid reactions.

The news regarding the incurable or serious disease in a child should preferably be disclosed to both parents simultaneously by the consultant with due concern, sympathy, and compassion.

The dialogue should be unhurried and parents should be encouraged to express their feelings, fears, and concerns by asking questions.

It has been rightly said by Bernie Siegel that “Our power to heal people and their lives seems to have diminished as dramatically as our power to cure diseases has increased by the technology boom”.

In the maze of scientific advances, we seem to have lost the human dimension. There is a need to resurrect the art of medicine.

There is no doubt that we should make sincere efforts not only to become knowledgeable and skillful physicians but we should strive to evolve as effective healers and above all good human beings.

These virtues of physicians are extolled in Charak Samhita “Though shall behave and act without arrogance and with an undistracted mind, humility, and constant reflection, though shalt pray for the welfare of all creatures.”

When you look at others with smiling, kind, and caring eyes, the act of looking becomes a prayer, a meditation, and a way of healing.

And when you perceive the outside world with calmness and clarity, your inner self reflects positive energy, which is endowed with great healing potential.

The principles of rational management of diseases and the art of medicine have been beautifully summed up by Sir Robert Hutchison in the following quote

In order to avoid therapeutic misadventures, there are five messages or pearls of wisdom encapsulated in the above quote.

- Many diseases are self-limiting and they recover spontaneously without any drugs. Nature, time, and patience are the three great physicians.

- We should not be enamored and fascinated or carried away to using newer drugs that have not withstood the test of time and we should remember the well-known dictum that “old is gold”.

- The art of medicine should not be sacrificed at the altar of technology.

- Patients should not be viewed as systems or organs but in their totality—body, mind, heart, soul, and society. A good physician treats the disease, the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.

- Medicines should be used only when indicated and they should not cause more harm to the patient than the disease itself for which they are prescribed.

We must use those medicines which have withstood the test of time with an assured efficacy and safety track record.

It is important to remember that no medicine is entirely safe and it has been cynically summed up by Oliver Wendell Holmes, “If the whole materia medica as being used now, could be sunk to the bottom of the sea, it would be better for all the mankind – but all the worse for the fishes.”

Integrated Management Of Neonatal And Childhood Illnesses (IMNCI)

WHO and UNICEF have adopted integrated management of neonatal and childhood illnesses strategy to provide a comprehensive or holistic approach to the welfare and survival of children.

Algorithms have been developed to diagnose and manage common childhood diseases. Apart from rational management of common diseases, health workers promote breastfeeding, provide immunizations, and health, and nutrition education.

The emphasis has shifted from purely curative services to a package of comprehensive health preventive, and promotive services at each contact of the health worker with the consumers.

The IMNCI strategy is being implemented in a phased manner for the teaching of undergraduate medical and nursing students throughout the country.

The Components of IMNCI

The IMNCI guidelines for case management of common diseases have been divided into two age categories, infants from birth up to 2 months and children above 2 months up to 5 years of age. The salient guidelines of IMNCI are listed below.

- The frontline workers, accredited social health activists (ASHAs), and Anganwadi workers (AWWs), after completing their IMNCI training are required to visit newborns at their households three times during the first week of life.

During their visits, the workers assess newborns, promote healthy practices, manage simple problems, and refer those with serious illnesses to healthcare facilities. - All sick infants up to 2 months of age must be assessed for “possible infection and jaundice” and they must be routinely evaluated for the major symptom of “diarrhea”.

- All sick children between 2 months and 5 years must be examined for “general danger signs” which indicate the need for an immediate referral or admission to the hospital.

They should be routinely assessed for major symptoms, like fever, cough, difficulty or rapid breathing, diarrhea, and ear problems. - All sick under-5 children must be routinely assessed for nutritional and immunization status, feeding problems, and other common day-to-day problems.

- A limited number of carefully selected clinical signs are used, based on their sensitivity and specificity, to diagnose the disease.

These signs were selected considering the conditions and ground realities prevalent at the first-level healthcare facilities. - On the basis of a combination of various signs, the child is classified into various groups (instead of diagnoses) and further divided into color-coded triage pink which requires an urgent referral or admission to a hospital, yellow when specific treatment is required through the outpatient department and green which calls for home management.

- The IMNCI guidelines address most but not all of the major reasons for which a sick infant or child is brought to the clinic.

The guidelines, for example, do not describe the management of trauma or other acute emergencies due to various accidents or injuries and also do not cover the care of the baby at birth. - The management procedures outlined in the IMNCI protocols use a limited number of essential drugs and encourage active participation by caretakers in the treatment of sick infants and children.

- In order to promote local health traditions and indigenous medicines, village health care workers and ASHAs are provided a kit of medicines containing AYUSH (Ayurvedic, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy) and allopathic or modern medicines to treat common day-to-day illnesses.

- An essential component of the IMNCI guidelines lays emphasis on providing counseling and guidance to caretakers about home care, feeding, administration of fluids, immunizations, healthy family life, etc.

And guidelines to return back to a healthcare facility for further management and follow-up.

Prognosis

Most parents and attendants are worried and concerned about the outcome of the disease.

They commonly ask “Will the child become alright” and “How soon he is likely to recover”? The outcome depends upon the nature and severity of the disease process and the type of host or victim who is afflicted with the disease.

The disease with an acute and sudden onset is likely to have either a dramatic recovery or a deadly outcome. Most diseases are self-limiting and they recover on supportive management without any medications.

Faith, willpower, positive thinking, and a sound genetic constitution are great healers. To augment the process of healing, the patient must have faith in his doctor and a doctor must have faith in himself and his medicines.

Infants below 3 months and children having protein-energy malnutrition and immunodeficiency state are likely to have poor outcomes.

The parents should be handled with due compassion and told about the likely outcome of the disease and possible side effects of the medications. They should be explained about the expected course of the disease.

For example, viral infections are usually self-limiting and likely to take 3–5 days for recovery, acute onset of vomiting may be followed by diarrhea after 12–24 hours, and a child with typhoid fever is likely to take 4–5 days to settle even after the start of specific antimicrobial therapy.

The physician must establish a rapport with the child and his parents to provide them with emotional support and win their faith, trust, and confidence.

The patients and attendants have emotional feelings and one should avoid saying that “nothing can be done (because something can always be done), don’t say “there is nothing wrong”, even when it is a functional disorder.

When a child is suffering from a chronic or incurable disease or an affliction with a lifelong disability, the parents are likely to respond with disbelief, anger, and shock.

The news about a disabling or deadly disease should preferably be given to both parents simultaneously with due concern, compassion, and empathy.

The facts should be explained in simple language without any medical jargon. The physician should allow the parents to vent their feelings and concerns, and try to answer their queries in an honest and unambiguous manner.

Physicians should be pragmatic but not pessimistic. It is important to remain positive and hopeful, which is a great healing force. Hope is the greatest healer and we should give a guarded but not hopeless prognosis.

It is important to remember that nature is supreme and miracles do happen. We should be careful and diplomatic in conveying the nature of the disease without hurting parental feelings.

Instead of bluntly saying, “Your child is mentally retarded”, it is better to say that the child is rather “slow” or has a “developmental delay”.

In Indian society, giving a spiritual context to parents of “special children” is useful to buffer their anxiety and feeling of hopelessness.

For example, you can say that “God has chosen you to provide care and comfort to this special child because you are so a compassionate, caring, and sensitive human being.”

The family should be encouraged to join the Self-Help Association of Parents to share their mutual concerns and difficulties and ensure the effective utilization of available specialized services.

End-of-Life Issues

During their career, physicians are likely to face several “end-of-life” situations. Despite all the technological advances, medicine can never achieve immortality.

It is as natural to die as to be born. When faced with a critically sick or dying child, the physician should allow the parents to

express their feelings and concerns and try to answer their queries in an honest and unambiguous manner.

In this situation, we should follow the well-known dictum” “talk less and listen more.” Coping the death of a child in the hospital is a painful and challenging experience for everybody concerned with the care of the child.

Death deflates our ego and teaches us humility and provides strength to handle the greatest reality of life with equanimity, composure, and confidence.

During the care of critically sick children in the intensive care unit, it is important to show due concern, care, and compassion to the parents/attendants, and keep them duly informed about the condition of their child.

It is important that physicians should not only provide state-of-the-art care to the child but also make the parents and attendants perceive that whatever was humanely possible, it was done for their child.

The family should be emotionally and spiritually prepared before the declaration of death. The news of death should be conveyed with utmost compassion but in no unmistakable terms that the child has died despite our best intentions and efforts.

When a child is conscious and dying, the parents should be at his bedside holding his hand and talking with him to allay his fears and provide him emotional support, for his journey to the unknown.

Leave a Reply