Intestinal Fistulae

Intestinal Fistulae Introduction:

Table of Contents

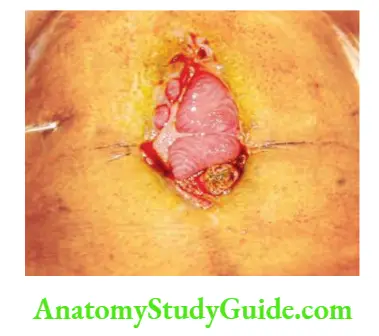

- Intestinal fistulae are abnormal communications between two portions of the intestine, between the intestine and some other hollow viscus, or between the intestine and the skin of the abdominal wall.

- When it involves skin and intestines, it is called enterocutaneous fistula.

- Despite significant advances in their management, intestinal fistulae remain a major clinical problem, with an overall mortality rate of 15 to 25%.

Intestinal Fistulae Classification:

Anatomical:

- Internal: Colovesical fistula

- External: Duodenal, jejunal fistula

- Mixed: Crohn’s disease

Depending on the Contents:

- Low output <200 ml

- Moderate output 200–500 ml

- High output >500 ml

Aetiology:

- Iatrogenic (70%)—postoperative: Injury to intestines unnoticed at the time of surgery or injury recognized at the time of surgery, sutured but has given way are prime causes of enterocutaneous fistulAnastomotic leak, partial or complete, is another important cause of enterocutaneous fistulMeticulous surgical techniques, gentle handling of the bowel, usage of the proper suture material (Vicryl and silk), ensuring adequate blood supply to the intestines which have to be anastomosed will largely prevent anastomotic leak.

- Stump blow out: Duodenal blow out: Typically happens 4–5 days following surgery.

- Inadequate resection of the diseased segment: In such situations, anastomosis may be in unhealthy bowel.

- Instrumentation: Oesophageal perforations are dangerous ones and can occur even with flexible scopies.

- Spontaneous (30%): Crohn’s disease, diverticular disease of the colon, appendicitis are also known to give rise to fistulae.

Local Factors Precluding Spontaneous Closure:

- Bleeding

- End fistula: Bowel discontinuity

- Foreign body: Swabs, tips of the suction tubes (detached), retained sponges or instruments

- Radiation

- Inflammation/infection/inflammatory bowel disease

- Epithelialisation of the tract is another important cause of the persistent fistula.

- Neoplasms

- Distal obstruction

- Multiple fistulae that do not heal as in Crohn’s or typhoid perforations.

- Lateral duodenal fistula does not heal because large volume of contents are poured into the second part of duodenum and there is no rest to the part.

- When the defect is more than 1 cm, and the track is more than 2 cm, fistula does not close (see clinical notes).

Management Principles:

It can be discussed under the following headings:

- Recognition and aetiology

- Phase of stabilization

- Nutrition—more details on page 38

- Investigative phase

- Phase of definitive management

- Surgery

- Skin care

- Abdominal wall defect

1. Recognition and Aetiology:

- Delay in recovery from paralytic ileus or a common phrase used—when the patient is not doing well are early indications of a leak or a breakdown of anastomosis. Once the fistula establishes, diagnosis is easy because the drain will start draining intestinal contents including food particles (if oral intake is started). Intra-abdominal collections, abscess, fever, sepsis are other features of leak.

- Recognising the cause is important because it can dictate treatment. To give an example: If any foreign body is left in the abdomen, exploration and removal may be urgently required.

- If a specific disease is suspected such as tuberculosis, antituberculous treatment may cure a fistula.

2. Phase of Stabilisation:

- Nil by mouth, total bowel rest, introduction of a nasogastric tube (Ryle’s tube) with continuous drainage decreases fistula output.

- Proton pump inhibitors decrease gastric secretions.

- Protection of skin is by liberal zinc oxide application.

- Common fluid and electrolyte problems seen in patients with GI fistula include dehydration, hyponatraemia, hypokalaemia and metabolic acidosis.

- They have to be corrected.

- Drainage of collections by CT or ultrasound-guided aspiration or pig tail catheter insertions.

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics, with anaerobic coverage.

3. Nutrition:

- Nutrition has been discussed in detail on Fluid-Electrolyte Balance and Nutrition. A few points worth mentioning are that more distal the fistula, less is the requirement of total parenteral nutrition (TPN). TPN is safe today. One may have to wait for 4–6 weeks with TPN for the final repair of complicated fistula such as lateral duodenal fistula or ileal fistula.

- Placement of nasogastric, nasojejunal tubes, percutaneous gastrostomy or jejunostomy for nutrition is an important step which can be done with the help of radiology and imaging department.

4. Investigative Phase:

- Routine biochemical and haematological investigations:

- Blood urea, serum creatinine, blood sugar

- Serum electrolytes

- Serum albumin, transferrin

- Blood culture helps in giving appropriate antibiotics

- Chest X-ray to rule out static pneumonia or ARDS, pleural effusions (source of sepsis also).

- Imaging studies:

- USG: Drainage of collections by catheters. If drainage persists, suspect fistulous communication.

- Fistulograms to define the exact site of fistula— proximal or distal—gastric or intestinal.

- Contrast CT abdomen: To detect collections, discontinuity, diseased segments, distal obstruction and foreign body. Extremely useful investigation in intestinal fistula.

- Colonoscopy and barium enema are other investigations used in specific situations such as colonic fistulae.

5. Phase of Definitive Management:

- Surgical intervention

- Drainage or aspiration of pus urgently when there is sepsis before doing an elective repair.

- Feeding jejunostomy as in high fistulae, e.g. duodenal or oesophageal fistula.

- Diversion/exclusion/colostomy/bypass are various other treatments depending upon the location of fistula.

- Definitive treatment: It includes restoration of continuity—resection and anastomosis, internal diversion or exteriorisation of bowel as in suspicious viability (mesenteric ischaemia or enteric perforations—friable bowel, known for leak and releak).

- Methods of skin care

- Pouches, stoma bags of different sizes are available.

- Creams and ointments—zinc or petroleum-based

- Suction catheter placed in situ: Low pressure suction 60–80 mmHg.

- Generally, dressings need to be changed every 4 hours. Pouch/reservoir system should be employed.

- Abdominal wall defects: Depending upon the size of the defect, immediate or delayed closure can be achieved with tension-releasing incisions on the external oblique or laparostomy and secondary suturing, skin grafting or by using prosthetic mesh such as Marlex or Prolene.

Small Intestinal Diverticular

Small Intestinal Diverticular Introduction:

Small intestinal diverticula are far less common than colonic diverticulMultiple sac-like mucosal herniations occur through weak points in the intestinal wall where blood vessels penetrate.

Incidence:

Diverticula are more common in duodenum than jejunum or ileum.

Small Intestinal Diverticular Pathophysiology:

- It is believed to develop as a result of abnormalities in peristalsis, intestinal dyskinesis and high segmental intraluminal pressures.

- They occur in the mesenteric border unlike Meckel’s which occurs in the antimesenteric border.

- Diet low in fibre and rich in fat and some visceral myopathy have been blamed for development of diverticula.

Small Intestinal Diverticular Clinical Features:

- Asymptomatic

- Occult blood in the stools—positive

- Anaemia and symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, pedal oedema

- Malabsorption—diarrhoea, flatulence, weight loss

- Pain abdomen, signs of peritonitis such as tenderness, guarding or localised abscess.

Small Intestinal Diverticular Investigations:

- Specific investigations are enteroclysis and enteroscopy.

- CT with contrast is the ideal investigation.

- Often diverticula are not suspected but a CT scan obtained for some pathology in the abdomen may reveal a localised abscess. Later, at laparotomy, it can turn out to be diverticula.

Small Intestinal Diverticular Treatment:

Resection and anastomosis of the bowel containing diverticul

Leave a Reply