Hepatobiliary System

Functions Of Liver:

Question 1. Enumerate important functions of liver.

Answer:

Important functions of liver are listed:

Important functions of liver:

- Protein metabolism and urea formation

- Carbohydrate metabolism: Includes gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, and glycogenesis

- Lipid metabolism

- Bilirubin formation from hemoglobin degradation

- Metabolism of vitamins and minerals

Read And Learn More: General Medicine Question And Answers

- Hormone metabolism

- Drug and alcohol metabolism

- Cholesterol metabolism

- Bile acid formation and bile secretion

- Synthesis of plasma proteins including coagulation factors

- Immunological function: Removal of gut endotoxins and foreign antigens

- Maintains core body temperature

- Maintains pH balance and correction of lactic acidosis

Liver Function Tests:

Question 2. Discuss the liver function tests. Discuss approach to jaundice.

Answer:

Liver Biochemistry:

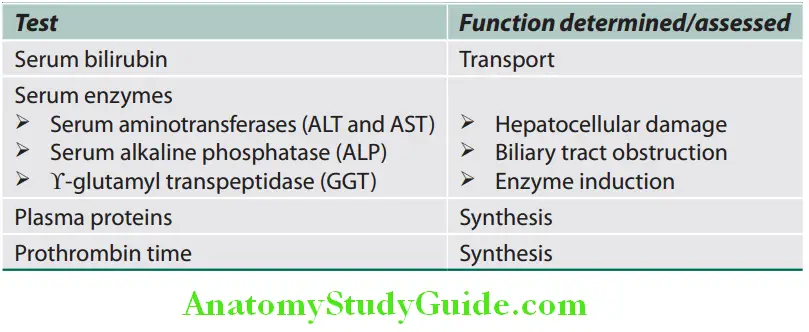

No single test alone can be used to assess liver function.

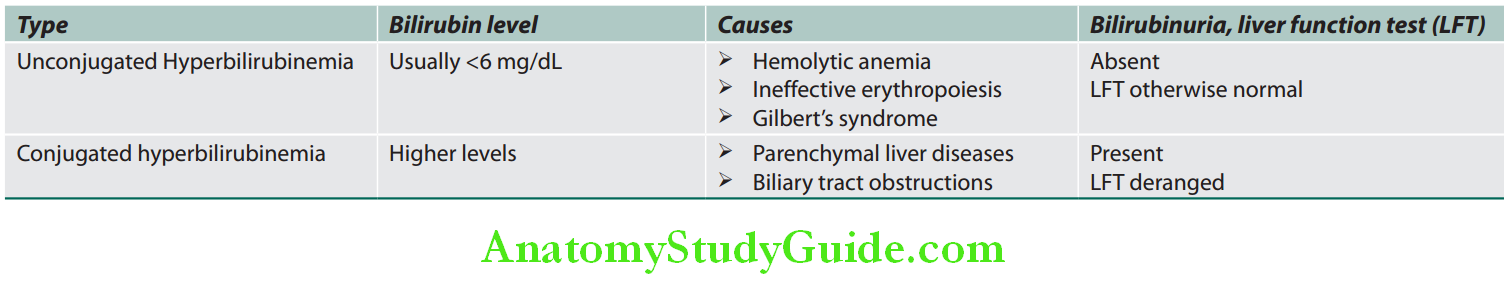

Serum Bilirubin:

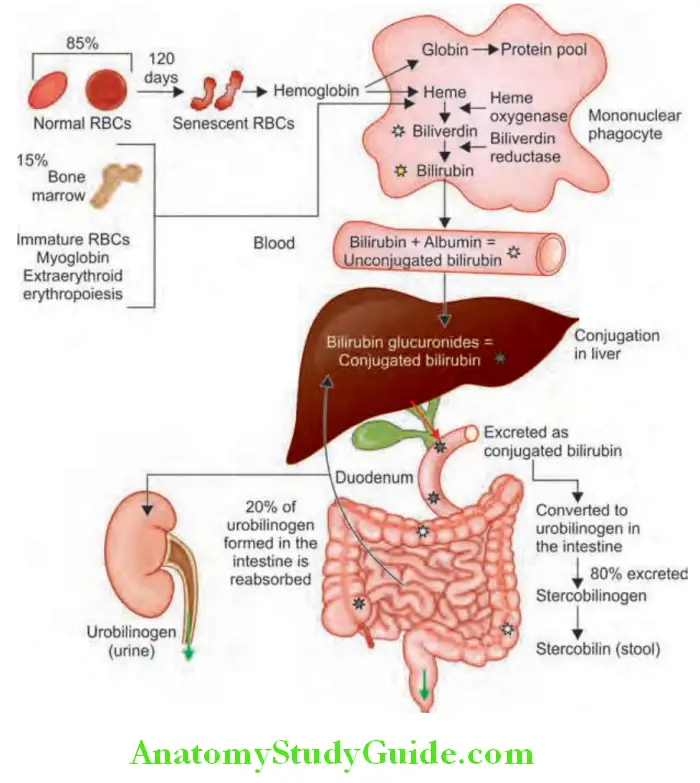

- Normal values of total serum bilirubin are between 0.3 and 3 mg/dL, with 95% of a normal population falling between 0.2 and 0.9 mg/dL (almost all unconjugated). Bilirubin is a degradation product of hemoglobin and hem-containing proteins. Bilirubin metabolism is summarized.

- Total serum bilirubin = Conjugated (direct) + unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin.

- The presence of conjunctival icterus suggests a total serum bilirubin level of at least 0 mg/dL level below which is called anicteric jaundice, but does not allow differentiation between conjugated and unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

- Tea or cola-colored urine may indicate the presence of bilirubinuria and thus conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

- Fluctuating hyperbilirubinemia is observed in gallstones, carcinoma of ampulla of Vater, chronic hepatitis, hemolytic anemias, and Gilbert’s syndrome.

Serum Enzymes:

- Enzymes that reflect damage to hepatocytes— aminotransferases (transaminases)

- These enzymes are present in hepatocytes and leak into the blood with liver cell damage. These include two enzymes, namely: aspartate aminotransferase (AST/SGOT), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT/SGPT).

- Present in hepatocytes and leak into the blood with liver cell damage

- Normal value: 10–40 U/L.

- Poor correlation between the degree of liver cell damage and level of aminotransferases

- Aspartate aminotransferase: Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic isoenzymes. High concentration also in heart, muscle, kidney, and brain. Raised in hepatic necrosis, myocardial infarction, muscle injury, and congestive cardiac failure.

- Alanine aminotransferase: Cytosolic enzyme. More specific for liver injury.

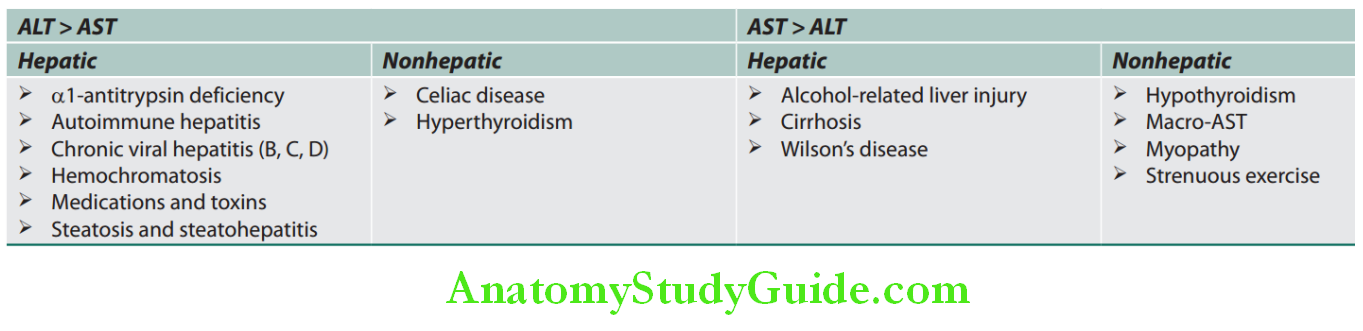

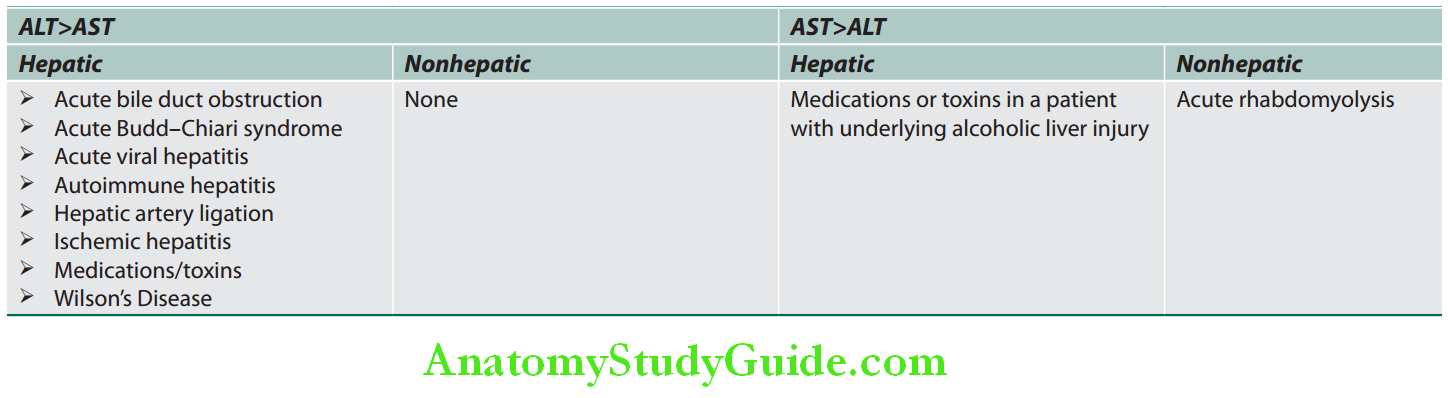

AST ALT ratio:

- AST: ALT >1: Chronic viral hepatitis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

- AST: ALT ratio >2:1 is suggestive, while a ratio >3:1 is highly suggestive of alcoholic liver disease. A low level of ALT in the serum in alcoholic patients is due to an alcohol-induced deficiency of pyridoxal phosphate.

Causes of Elevated Serum Aminotransferases:

Chronic mild elevations (<150 U/L):

Acute severe elevations (>1,000 U/L):

Enzymes that reflect cholestasis:

These include three enzymes:

- Alkaline phosphatase (ALP)

- 5’-nucleotidase

- ϒ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT).

Question 3. Write short answer on causes/diseases with elevated/very high serum alkaline phosphatase.

Answer:

Alkaline phosphatase:

- Many distinct isoenzymes—liver, bone, kidney, placenta, small intestine, origin can be determined by electrophoretic separation.

- Normal serum level: 3–13 KA units (80–240 IU/L).

- Raised levels of liver-derived ALP are not totally specific for cholestasis.

- Low levels: Wilson’s disease, with fulminant hepatitis and hemolysis, possibly because of reduced activity of the enzyme owing to displacement of the cofactor zinc by copper. Ratio of ALP to total bilirubin of <2 is quite specific for Wilson’s disease.

- Raised serum ALP levels:

- <5 times: Hepatocellular jaundice

- >4 times:

- Obstructive jaundice (intrahepatic or extrahepatic obstruction)

- Infiltrative liver diseases, e.g., cancer, metastases, and amyloidosis

- Bone lesions with rapid bone turnover, e.g., Paget’s disease

- Primary biliary cirrhosis

ϒ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT):

- Microsomal enzyme is present in liver, renal tubules, pancreas, and intestine.

- Identify the source of isolated elevation in serum ALP (GGTP is normal in bone disease)

- Screening test for alcoholism: If ALP is normal, raised serum γ-GT is a good guide to alcohol intake of more than 60 g/day. (Detection of alcohol abuse in patients who deny it).

- Elevated GGT levels:

- Biliary obstruction

- Alcoholism

- Liver parenchymal damage

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver

- Other causes: Chronic obstructive lung disease, diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism, obesity, and renal failure.

- Patients taking phenytoin, barbiturates, and antiretroviral therapy—nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and abacavir

5-nucleotidase:

- Microsomal enzyme has similar significance as that of GGT.

- 5′NT levels are not increased in bone disease but are increased in hepatobiliary disease.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): Not useful in diagnosis of liver diseases

- Moderate elevations: Ischemic hepatitis and hepatic metastasis.

- ALT/LDH ratio >5 suggests ischemic hepatitis while ratio <5 is seen with paracetamol toxicity.

Biosynthetic Function of the Liver:

Tests that measure synthetic function of the liver.

Plasma Proteins:

Serum albumin:

- It is synthesized exclusively in liver and used as a marker of synthetic function.

- Normal serum albumin level: 4–5.5 g/100 mL and albumin has a half-life of around 20 days.

Serum albumin Significance:

- Low levels: Serum albumin is an excellent marker of hepatic synthetic function. Hypoalbuminemia is observed in chronic liver diseases such as cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis and usually reflects severe liver damage and decreased albumin synthesis. A falling serum albumin level in liver disease is a bad prognostic sign.

- Apart from chronic liver disease, it may be observed in chronic inflammation, sepsis, expanded plasma volume, and renal or gastrointestinal (GI) loss.

Serum globulins:

- They constitute a group of proteins made up ofϒ-globulins (immunoglobulins) synthesized by B lymphocytes and α- and β-globulins synthesized primarily by hepatocytes.

- Normal serum globulin level: 5–5 g/100 mL.

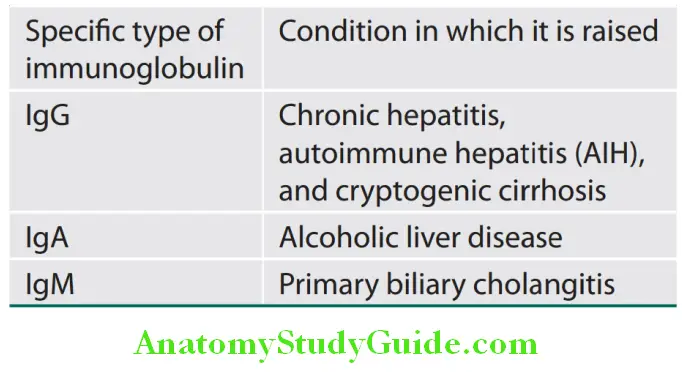

- Significance: ϒ-globulins are increased in chronic liver disease (e.g., chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis). Increase in the concentration of specific isotypes of ϒ-globulins (immunoglobulins) is helpful in the recognition of certain chronic liver diseases.

- Cirrhosis: Plasma proteins show decrease in albumin and increase in ϒ-globulin.

Specific types of elevated immunoglobulin and its associated conditions:

Coagulation factors:

- Liver produces all the coagulation factors, except factor VIII.

- Vitamin K is required for the activation of coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X.

- The coagulation factors have short half-life time. Thus, measurement of the clotting factors is the single best measure of hepatic synthetic function and useful in both the diagnosis and assessing the prognosis of acute parenchymal liver disease.

- Prothrombin time:

- Prothrombin time depends on factors 1, 2, 4, 7, and 10.

- Normal value is 11–15 seconds.

- Prothrombin time collectively measures factors 2, 5, 7, and 10.

- Causes of prolonged prothrombin time are listed.

- Unlike the serum albumin, the prothrombin time allows an assessment of current hepatic synthetic function; factor VII has the shortest serum half-life (6 hours) of all the clotting factors.

Read And Learn More: General Medicine Question And Answers

Causes of prolonged prothrombin time:

- Severe liver damage: Acute hepatitis (e.g., viral hepatitis), cirrhosis

- Deficiency of vitamin K

- Obstructive jaundice that reduces vitamin K absorption

- Fat malabsorption

- Poor intake

- Antibiotic therapy which produces destruction of vitamin

- Producing commensals

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Drugs and toxins: Warfarin, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, dabigatran, viper envenomation, anticoagulant rodenticide poisoning

Ceruloplasmin:

- It is an acute-phase reactant synthesized by the liver.

- In blood, it binds to copper and acts as a major carrier for copper.

- Normal plasma level: 20–60 mg/dL

- Causes of elevated levels: Infections, liver diseases, obstructive jaundice, rheumatoid arthritis, and pregnancy.

- Causes of decreased levels: Wilson’s disease (due to decreased rate of synthesis), neonates, Menkes disease, kwashiorkor, marasmus, protein-losing enteropathy, and copper deficiency.

Cholesterol:

- It is synthesized in the liver. Advanced liver disease may be associated with very low cholesterol. However, primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) may be associated with markedly raised cholesterol. Similarly, a low urea level also indicates severe liver dysfunction. Liver functions tests and their significance are summarized.

Serum autoantibodies:

- Antimitochondrial antibody (AMA): Antinuclear, smooth muscle (actin), liver/kidney microsomal antibodies, antinuclear cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA).

Summary of main liver function tests and its signifiance:

Urine Tests:

Bilirubin in urine:

- Normally, bilirubin cannot be detected in urine.

- In unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, urine does not contain bilirubin (acholuric jaundice). Thus, absence of bilirubin in urine in a jaundiced patient suggests unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

- In conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, urine contains bilirubin.

- Thus, bilirubinuria in a jaundiced patient points to conjugated hyperbilirubinemia (hepatobiliary disease).

- Urinary bilirubin is detected by Fouchet’s test.

Urine urobilinogen:

- Urobilinogen is normally present in urine in trace amounts (1–2 mg/dL) and is insufficient to cause a significant positive reaction.

- Causes of increased urobilinogen in urine:

- Causes of absent urobilinogen: In obstructive jaundice (bilirubinuria present), bilirubin does not reach the intestine and so is not converted into urobilinogen.

- Urinary urobilinogen is detected by Ehrlich’s aldehyde test.

Causes of increased urobilinogen in urine:

Hemolytic anemias (without bilirubin in urine):

- Thalassemia

- Sickle-cell anemia

- Hereditary spherocytosis

Liver diseases (bilirubinuria present):

- Preicteric phase of infective hepatitis

- Drugs or toxic hepatitis

- Cirrhosis

α-Fetoprotein (AFP):

- α-fetoprotein is normally produced by fetal liver cells and its levels falls to low levels after birth.

- Causes of elevated levels ofα-fetoprotein are:

- Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

- Carcinomas of stomach, pancreas, gallbladder, bile ducts, and lungs

- Teratomas

Diagnostic Procedures:

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography:

Question 4. Write short note on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Answer:

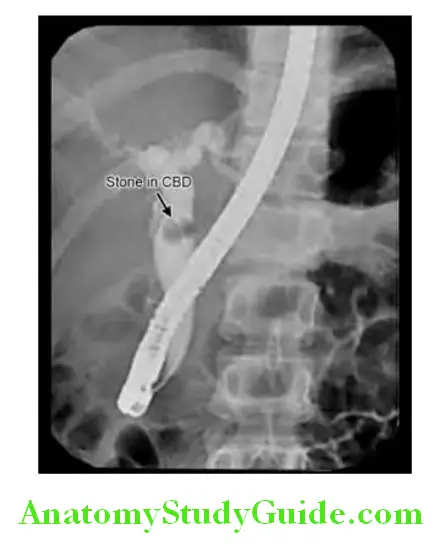

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a technique used to outline the biliary and pancreatic ducts.

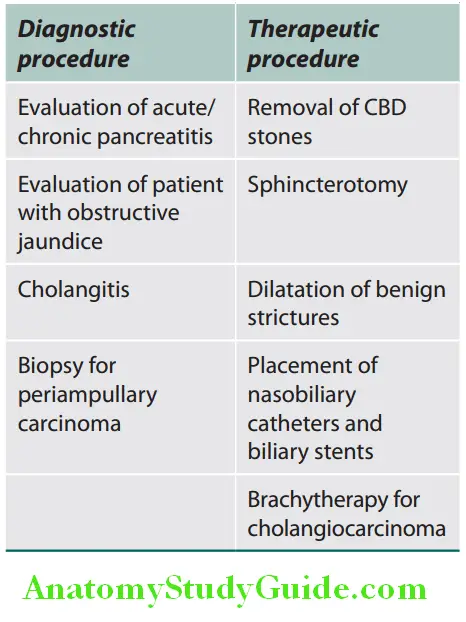

Diagnostic Procedure:

An endoscope is passed into the second part of the duodenum and cannulation of the ampulla. Contrast is injected into the biliary tree and the patient is screened radiologically. ERCP with stone in the common bile duct (CBD).

Diagnostic Uses of ERCP:

Diagnostic Complications:

The complication rate in diagnostic ERCP is 2–3%. Complications include pancreatitis, cholangitis, bleeding, and duodenal perforation.

Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography:

Question 5. Write short note on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.

Answer:

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a noninvasive technique largely replacing diagnostic (but not therapeutic) ERCP.

Technique:

A heavily T2-weighted sequence enhances visualization of the water-filled biliary (intrahepatic ducts) and pancreatic ducts (extrahepatic ducts). It produces high-quality images of ductal anatomy.

Advantages of MRCP over ERCP Indications:

- Diagnosis of bile duct obstruction and pancreatic duct abnormalities, e.g., choledocholithiasis, malignant obstruction of bile and pancreatic ducts, congenital anomalies, and chronic pancreatitis.

- Unsuccessful ERCP or a contraindication to ERCP (as in patients with cardiorespiratory compromise, renal failure).

Advantages of MRCP over ERCP:

- No need for contrast media or ionizing radiation

- Images can be acquired faster

- Less operator dependent

- No risk of pancreatitis

Endoscopic Ultrasound:

Question 6. Write a short note on endoscopic ultrasound.

Answer:

Endoscopic Ultrasound Procedure:

In endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), a small high-frequency ultrasound probe is placed on the tip of an endoscope and placed by direct vision into the duodenum.

Endoscopic Ultrasound Advantages:

Gradually replacing diagnostic ERCP:

- Close proximity of the ultrasound probe to the pancreas and biliary tree allows high-resolution ultrasound imaging.

- Accurate staging of small, potentially operable, pancreatic tumors (e.g., neuroendocrine tumors) can be done.

- It is less invasive method for bile duct imaging.

Endoscopic Ultrasound Uses:

Diagnostic:

- Imaging pancreatic and biliary diseases, e.g., choledocholithiasis, pancreatic and biliary cancers, and cystic lesions of the pancreas

- Ampullary carcinoma: To know the local extension of tumor and regional lymph node metastasis that cannot be evaluated

by ERCP - Performing fine-needle aspiration under EUS guidance from suspicious lesions for confirmation of malignancy

Therapeutic:

- Increasingly used for guided interventions:

- To reduce pain in patients with unresectable pancreatic carcinoma, for injecting bupivacaine and alcohol into the celiac ganglia.

- Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts.

Endoscopic Ultrasound Disadvantages:

- Cost is high.

- High degree of training is required.

Liver Biopsy:

Question 7. Write short note on the indications, significance, and complications of liver biopsy.

Answer:

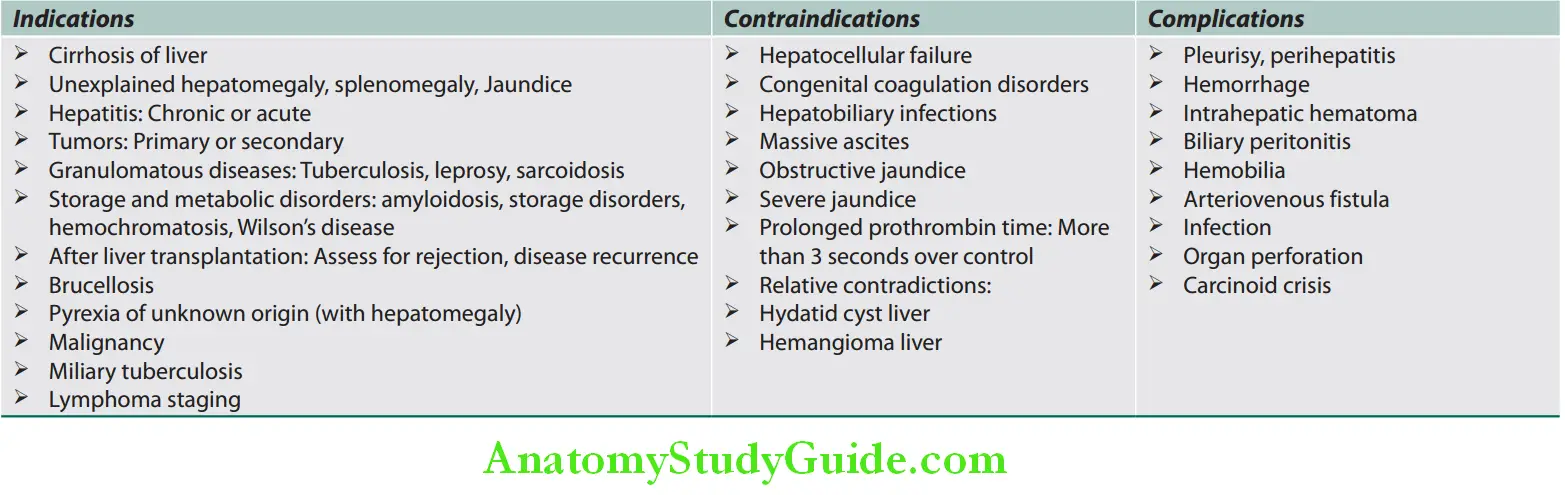

Percutaneous liver biopsy is an invasive procedure that can be performed with or without radiographic guidance. Indications, contraindications, and complications of liver biopsy.

Indications, contraindications, and complications of liver biopsy:

Jaundice:

Question 8. List the causes of jaundice. How will you arrive at the etiology of jaundice? Give the points of differentiation in clinical features and investigations.

Answer:

Jaundice Defiition:

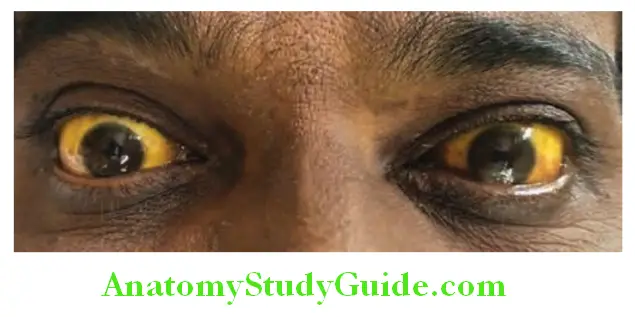

Jaundice (icterus) is defied as yellowish pigmentation of skin, mucus membranes, and sclera due to increased levels of bilirubin in the blood. Th scleral involvement is because of its rich elastic tissue that has special affity for bilirubin.

- Normal serum bilirubin level: In normal adults, it ranges from 0.3 to 2 mg/dL.

- Jaundice is clinically detected when the serum bilirubin level is above 0–5 mg/dL. With severe disease, the levels may be as high as 30–40 mg/dL.

- Latent jaundice is the term used when serum bilirubin is more than 2 mg/dL but less than 5mg/dL.

- Carotenemia is characterized by yellowish pigmentation of skin by carotene but not of sclera. Quinacrine consumption also causes yellowish discoloration of skin and mucus membranes.

Classifiation of Jaundice:

Question 9. Write short note on causes of indirect/unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

Answer:

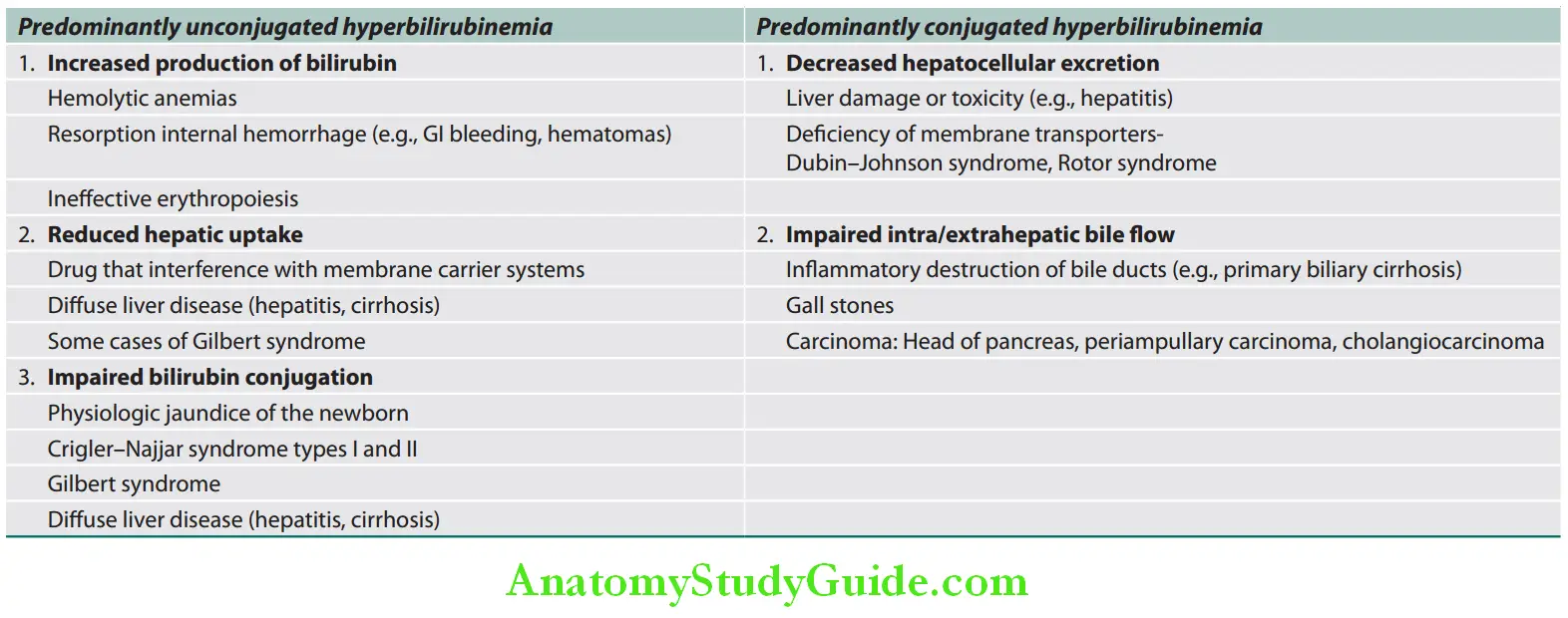

Jaundice can be classified in two ways:

1. Based on the underlying cause:

- Predominantly unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia

- Predominantly conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

Classification of jaundice:

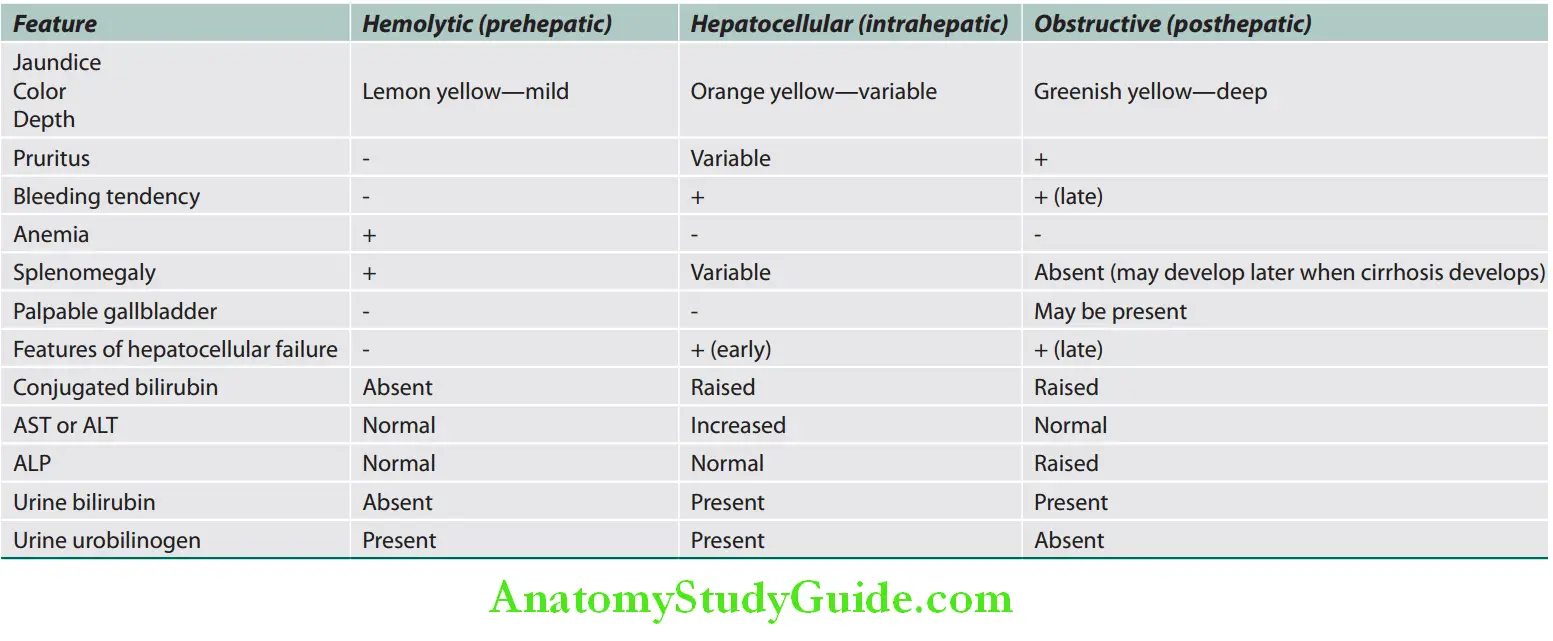

2. Based on pathological mechanism:

- Hemolytic (prehepatic) jaundice

- Hepatocellular jaundice (hepatic)

- Obstructive jaundice (posthepatic).

Classification of jaundice based on the pathological mechanism:

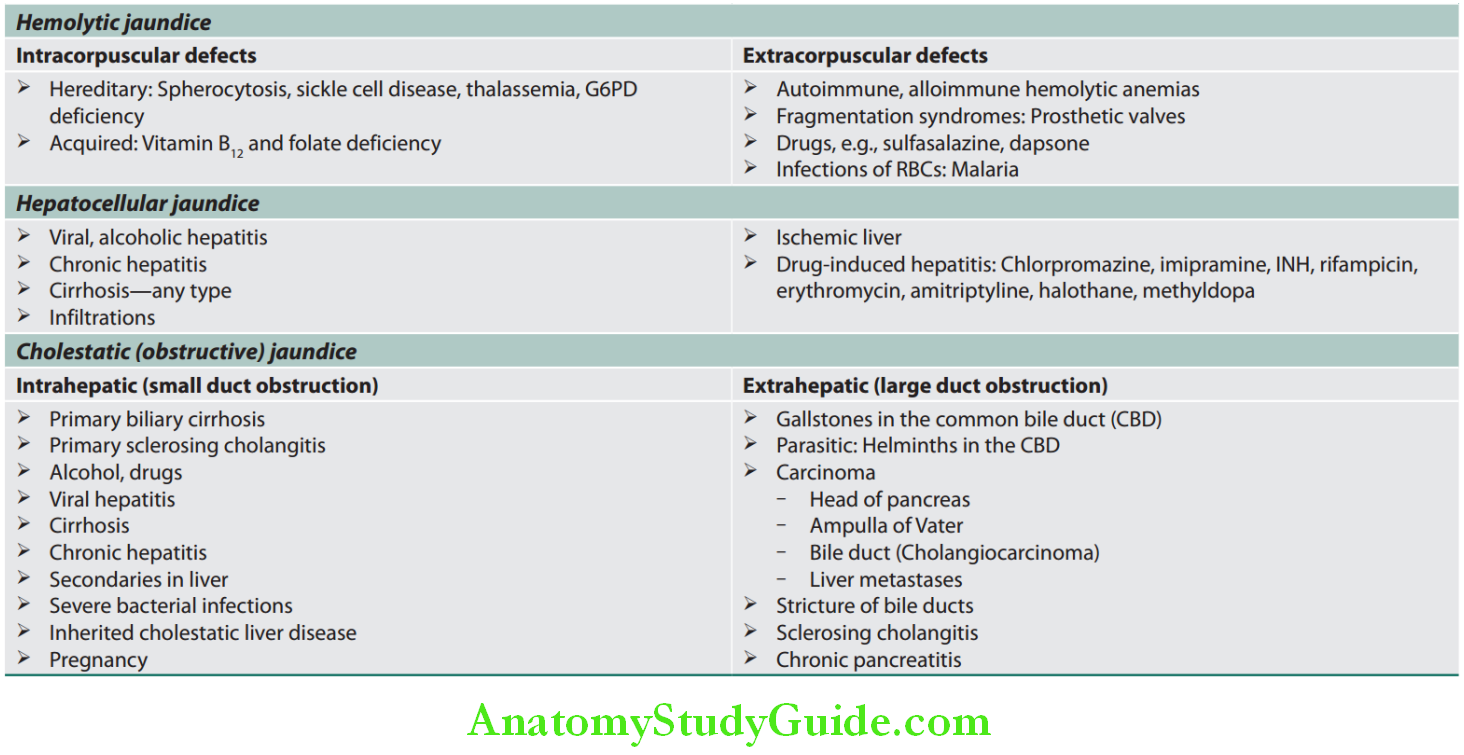

Hemolytic Jaundice:

Question 10. Write short note on prehepatic jaundice.

Answer:

- Increased destruction of red blood cells or their precursors causes increased production of bilirubin.

- Unconjugated bilirubin accumulates in the plasma and results in jaundice.

- Jaundice is usually mild because normal liver can easily handle the increased bilirubin production.

Question 11. How do you clinically differentiate hemolytic jaundice, hepatocellular jaundice, and obstructive (cholestatic) jaundice?

Answer:

Hemolytic jaundice Clinical features:

- Pallor due to anemia

- Mild jaundice without any signs of liver disease

- Hepatosplenomegaly due to increased activity of reticuloendothelial system.

- Gallstones and leg ulcers may be seen depending on the cause of anemia.

- Dark stools due to increased stercobilinogen in stool

- Urine turns dark yellow on standing. This is due to increased urobilinogen being converted to urobilin in urine.

Hemolytic jaundice Investigations:

- Peripheral smear—shows features of hemolysis

- Predominantly unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Serum bilirubin is raised (<6 mg%).

- No bilirubin in urine, because the unconjugated bilirubin is not water soluble and cannot pass into the urine; hence the term “acholuric jaundice”

- Urinary urobilinogen is increased (more than 4 mg/24 hours).

- Other LFTs (e.g., serum ALP, transferases, and albumin) are normal; however, LDH is increased.

Hepatocellular Jaundice:

- Hepatocellular jaundice occurs as a consequence of parenchymal liver disease which leads to an inability of the liver to transport bilirubin across the hepatocyte into the bile.

- Defect in bilirubin transport across the hepatocyte may occur at any point between the uptake of unconjugated bilirubin into the hepatocyte and transport of conjugated bilirubin into biliary canaliculi.

- In hepatocellular jaundice, both unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin level rise in the blood

Hemolytic jaundice Investigations:

- Raised transaminases (AST and ALT): Acute jaundice with AST > 1000 U/L is highly suggestive of an infectious cause (e.g. hepatitis A, B), drugs (e.g., paracetamol) or hepatic ischemia.

- Imaging

- Liver biopsy

Cholestatic (Obstructive/Surgical) Jaundice:

Question 12. Write short note on causes and features of obstructive jaundice.

Answer:

- Cholestasis means failure of bile flow. Its cause may be anywhere between hepatocyte and duodenum.

- Cholestatic jaundice is usually a “surgical jaundice” meaning a cause that requires surgical intervention.

- Cholestasis can be intrahepatic or extrahepatic.

- Consequences of cholestasis:

- Retention of bile acids and bilirubin in the liver and blood

- Deficiency of bile acids in the intestine

Cholestatic Clinical features:

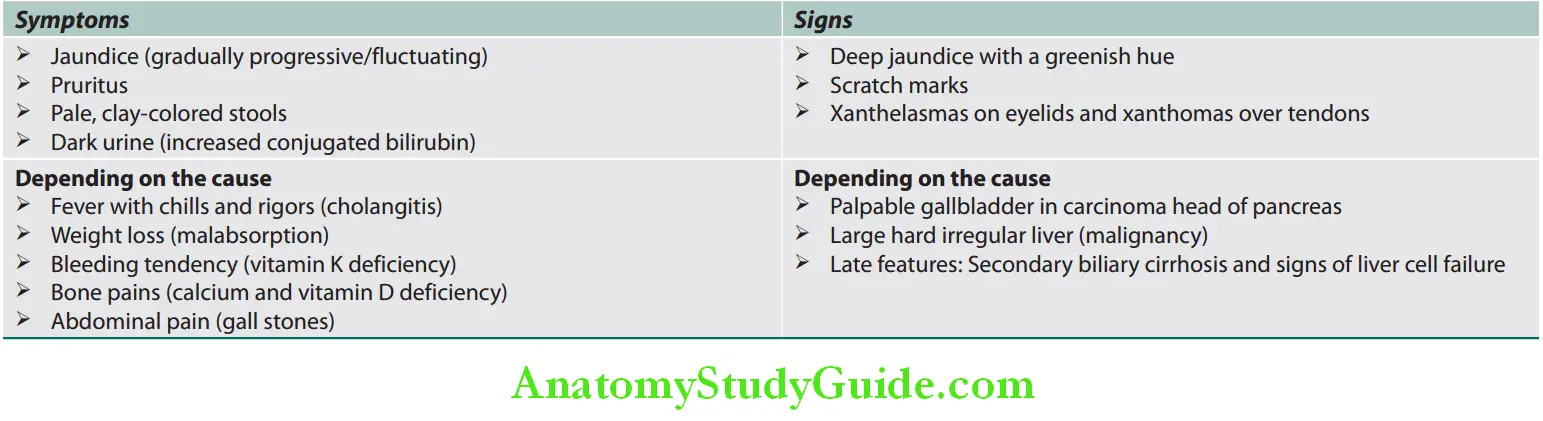

Symptoms and signs of cholestatic jaundice:

Cholestatic Investigations:

Serum findings:

- Serum bilirubin is markedly raised and is predominantly conjugated hyperbilirubinemia

- Serum ALP is markedly raised (3–4 times that of normal).

- Minimal biochemical changes of liver parenchymal damage.

- Antimitochondrial antibody (in primary biliary cholangitis).

Urine findings:

- Bilirubin present

- Urobilinogen absent

Clinical features useful in differentiating different types of jaundice are listed in Table:

Clinical features useful in diffrentiating diffrent types of jaundice:

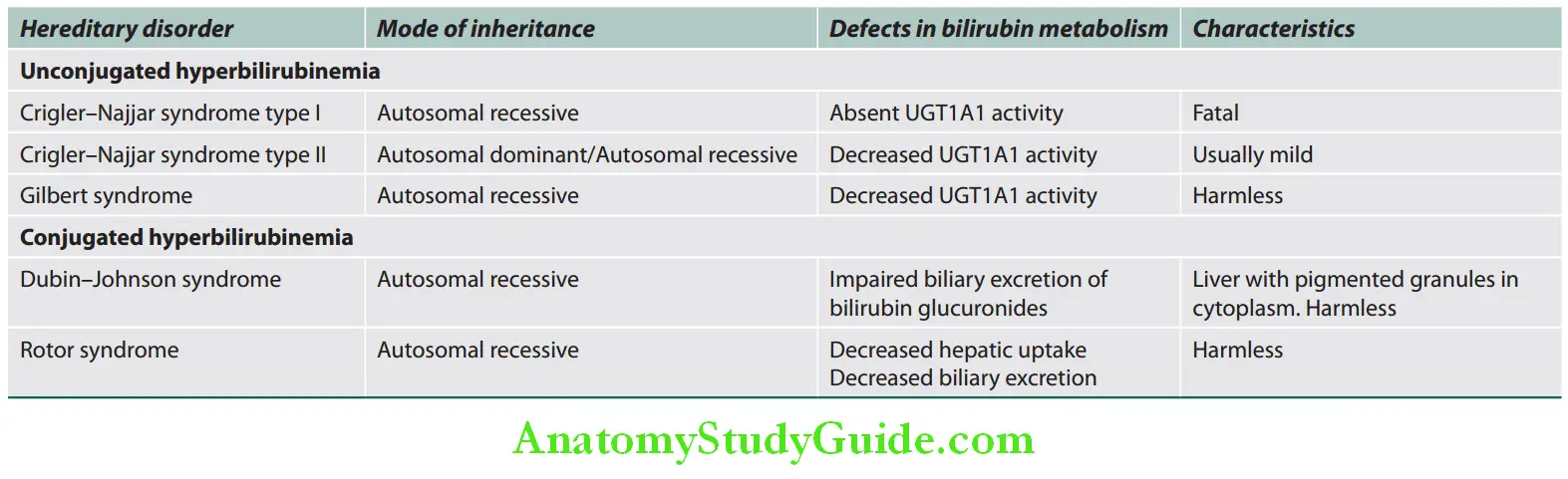

Congenital Nonhemolytic Hyperbilirubinemias:

Question 13. List congenital nonhemolytic hyperbilirubinemias.

Answer:

Various congenital nonhemolytic hyperbilirubinemias are listed in Table:

Congenital nonhemolytic hyperbilirubinemias:

- Individuals with Crigler–Najjar or Gilbert syndrome cannot ConjuGate bilirubin.

- Individuals with Rotor syndrome or Dubin–Johnson syndrome cannot get RiD of DiRect bilirubin.

Gilbert Syndrome:

- Relatively common, autosomal recessive, harmless, inherited disorder

- Etiology: Mutations in UGT1 gene—inadequate synthesis of UGT1A1 enzyme (about 30% of normal)

- Clinical features:

- More common in males

- Usually asymptomatic, jaundice is incidentally detected.

- Mild, chronic unconjugated fluctuating hyperbilirubinemia.

- No other functional derangements

- Severity of jaundice increases with infections, fatigue, exertion, and fasting

- Physical examination is otherwise normal.

- Investigations:

- Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia (less than 6 mg %)—raised bilirubin levels during fasting is the most common diagnostic tool.

- Urine: Increased urobilinogen and absent bilirubinuria

- Peripheral smear, reticulocyte count, and serum haptoglobin: Normal

Gilbert Syndrome Treatment: Usually no treatment is required. Glucuronosyltransferase activity may be increased by administering phenobarbital 60 mg BD.

Crigler–Najjar Syndrome Type 1:

- Rare, autosomal recessive disorder, invariably fatal

- Etiology: Due to complete absence of hepatic UGT1A

- Chronic, severe, unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia with severe jaundice, icterus and death secondary to kernicterus within 18 months of birth.

- Bile does contain conjugated bilirubin; hence it is colorless.

- Liver is morphologically normal by light and electron microscopy.

Crigler–Najjar Syndrome Type 1 Treatment: Daily phototherapy and liver transplantation. Phenobarbital has no effect.

Crigler–Najjar Syndrome Type 2:

- Less severe, nonfatal disorder, also known as Arias syndrome

- Autosomal recessive inheritance in most cases

- Partial deficiency of UGT1A1 enzyme (10% of normal).

- Jaundice is milder than type I and does not develop kernicterus

Crigler–Najjar Syndrome Type 2 Treatment: Treatment includes ultraviolet light therapy and liver transplantation. Phenobarbital treatment can improve bilirubin glucuronidation by inducing hypertrophy of hepatocellular endoplasmic reticulum.

Dubin–Johnson Syndrome:

- Benign autosomal recessive disorder

- Etiology: Complete absence of the multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2) which is required for secretion of conjugated bilirubin from hepatocytes into canaliculThis leads to defect in hepatocellular excretion of bilirubin glucuronides across biliary canalicular membrane.

- Clinical features: Chronic, recurrent conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, generally after puberty.

- Investigations:

- Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia (usually 2–5 mg/dL)

- Bromosulfthalein (BSP) clearance—impaired with reflux into blood at 90 minutes

- Bilirubinuria

- Gallbladder is usually not visualized on oral cholecystography.

- Liver biopsy: Dark pigment in centrilobular hepatocytes, coarse melanin-like pigmented granules within the enlarged lysosomes, present in the cytoplasm. Pigment composed of polymers of epinephrine metabolites.

No treatment is required in most cases. Most of the patients have a normal life expectancy.

Rotor Syndrome:

- Rare, autosomal recessive, asymptomatic conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

- Defective organic anion transport proteins; (OATP) 1B1 and 1B3 in hepatocytes → impaired transport and reduced storage capacity of conjugated bilirubin

- Clinical presentation—mild jaundice.

- Investigations:

- Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia

- Bilirubinuria

- BSP clearance test—impaired without reflux back into blood

- Gallbladder is visualized on oral cholecystography.

- Liver is morphologically normal. No pigmentation

Charcot’s Triad:

Question 14. Write short note on Charcot’s triad.

Answer:

It consists of following in the presence of stones in bile ducts:

- Pain in the right hypochondrium

- Intermittent or persistent jaundice

- Fever with chills and rigors due to acute cholangitis.

Reynolds’ pentad adds mental status changes and sepsis to the triad.

Courvoisier’s Law:

Question 15. Describe Courvoisier’s law.

Answer:

In obstruction of CBD due to a stone, the gallbladder as a rule is impalpable (no distension). This is because the gallbladder is usually already shriveled, fibrotic, and nondistensible and hence will not be palpable.

In obstruction from other causes (e.g., carcinoma head of pancreas) distension of the gallbladder is common and hence gallbladder may be palpable.

Exceptions of Courvoisier’s law:

- Double impaction: Stones, simultaneously occluding the cystic duct and the distal.

- Pancreatic calculus obstructing the ampulla of Vater

- Oriental cholangiohepatitis

- Periampullary carcinoma in patients with cholecystectomy

- Mirizzi syndrome

Viral Hepatitis:

Question 16. Describe the etiology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical features, and treatment of viral hepatitis.

(or)

Write short note on the diagnosis, prevention, and management of acute viral hepatitis.

(or)

List the viruses causing acute hepatitis.

Answer:

Viral Hepatitis Etiology:

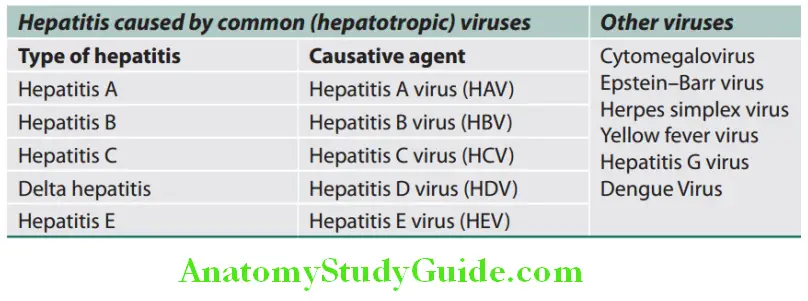

Various causes of acute hepatitis and types and causes of viral hepatitis:

Causes of acute hepatitis:

- Viral hepatitis

- Other infections: Leptospirosis, malaria, dengue, brucellosis

- Alcohol

- Drugs: Paracetamol, isoniazid (INH), rifampicin, halothane

- Ischemic and vascular:

- Cardiogenic shock

- Hypotension

- Cocaine, methamphetamine, and ephedrine

- Acute Budd–Chiari syndrome

- Toxins: Amanita, carbon tetrachloride, and yellow phosphorous

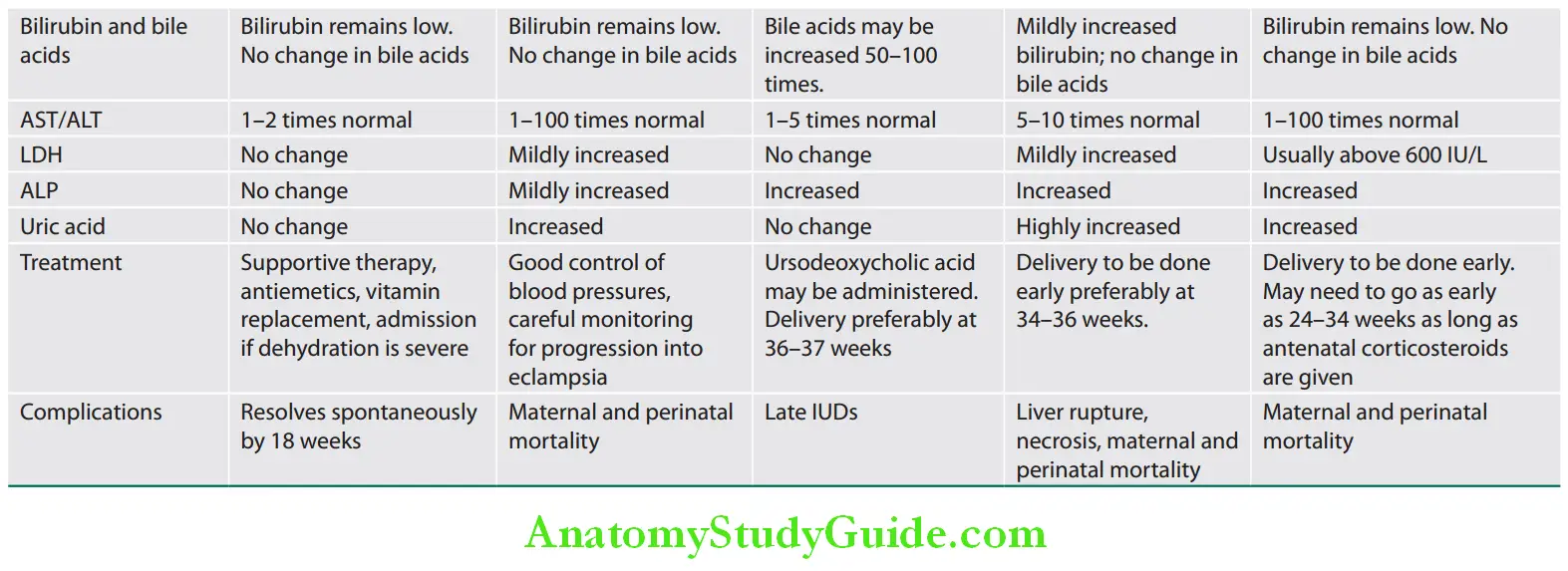

- Pregnancy-related:

- Preeclampsia

- Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

- HELLP syndrome

- Immunological: Autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Metabolic or hereditary:

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Hemochromatosis

- Wilson’s disease

Types of viral hepatitis:

Hepatitis A:

Question 17. Discuss the clinical features, investigations, and management of hepatitis A infection.

Answer:

Hepatitis A Etiology:

- Caused by hepatitis A virus (HAV) which is a nonenveloped, 27-nm, RNA virus belonging to the Picornavirus group.

- Hepatitis A is the most common type of viral hepatitis, often occurs in epidemics.

- It most commonly affects children and young adults.

- Overcrowding and poor sanitation facilitate the spread.

Source of Infection:

- The only source of infection is acutely infected person.

- Virus replicates in the liver, is excreted in bile and then excreted in stool/feces of infected persons for about 2 weeks before the onset of symptoms and then for a further 2 weeks or so.

Mode of Spread:

Fecal-oral route (either via person-to-person contact or consumption of contaminated food or water). In outbreaks, it spreads through water, milk, and shell fish.

Incubation Period:

- 15–45 days (average 28 days).

- There is no carrier state.

- Clinical features are discussed together.

Extrahepatic Manifestations:

Extrahepatic manifestations are less frequent in acute HAV infection than in acute hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.

Most common manifestations are quickly fading rash (14%) and arthralgias (11%) while uncommon are myocarditis, thrombocytopenia, aplastic anemia, red cell aplasia, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, glomerulonephritis, and arthritis, in which immune-complex disease is believed to play a pathogenic role.

Prevention and Prophylaxis:

- Maintain good hygiene and improve social conditions. HAV is resistant to chlorination but is killed by boiling water for 10 minutes.

- Active immunization: A formaldehyde-inactivated HAV vaccine (contains the single HAV antigen) for active immunization and can be used in individuals above the age of 2 years. It probably provides lifelong immunity.

- Passive immunization: Normal human immunoglobulin [0.02 mL/kg intramuscularly (IM)] made from pooled human plasma is used if exposure to HAV is <2 weeks and can protect from HAV infection for 3 months. HAV vaccine should also be administered.

Hepatitis B:

Question 18. What are the common causes of viral hepatitis? Discuss the clinical features, complications and management of hepatitis B infection.

Answer:

Hepatitis B Etiology:

Hepatitis B is caused by HBV which is a hepatotropic DNA virus belonging to the family Hepadnaviridae.

Structure and Genome of HBV:

Complete infective virion (HBV virion) is called as Dane particle. It is spherical 42-nm particle and double-layered comprising an inner core or nucleocapsid (27 nm) surrounded by an outer envelope of surface protein (HBsAg).

Viral genome: It consists of partially double-stranded circular DNA and has four genes.

- HBsAg (hepatitis B surface antigen) (S gene): HBsAg is a product of S gene which is secreted into the blood in large amounts. HBsAg is immunogenic.

- HBcAg (hepatitis B core antigen) (C gene): The C gene produces two antigenically different products:

- Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg): It remains intracellular within the hepatocytes and does not circulate in the serum. Hence, it is not detectable in the serum of patients.

- (HBeAg) (hepatitis B e antigen): It is secreted into serum and is a surrogate (substitute) marker for high levels of viral replication. It is essential for the establishment of persistent infection.

- HBV polymerase (P gene): A polymerase (Pol) is a product of P gene and DNA polymerase enzyme is needed for virus replication.

- HBxAg (X gene): HBx protein is necessary for virus infectivity and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of liver cancer in HBV infection.

Source of infection: Human suffering from hepatitis (acute/chronic) or carriers is the only source of infection. HBV is100 times as infectious as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and 10 times as infectious as hepatitis C virus (HCV).

Mode of Transmission:

Question 19. Write short note on mode of transmission of hepatitis B (serum hepatitis).

Answer:

- Vertical/congenital transmission: Transmission from mother [who is carrier for HBV (90% HBeAg+ve, 30% HBeAg–ve)] to child may occur in utero, during parturition, or soon after birth. It not transmitted by breastfeeding.

- Horizontal transmission: It is the dominant mode of transmission.

- Parenteral: It is the major route of transmission but occasionally nonparenteral.

- By percutaneous and mucus membrane exposure to infectious body fluids, through minor cuts/abrasions in the skin or mucus membranes. In children, it can be transmitted through minor abrasions or close contact with other children. HBV can survive for long periods on household articles, e.g., toys, toothbrushes, and may transmit the infection.

- Intravenous route: HBV can transmitted through transfusion of unscreened infected blood or blood products. This mode of spread is rare now, because of routine screening of all blood donors for HBV and HCV. Intravenous drug abuse with sharing of needles and syringes, tattooing, and acupuncture are other ways of developing infection.

- Close personal contact: Nonparenteral route of transmission includes spread through body fluids (virus can be found in these fluids) such as saliva, urine, semen, and vaginal secretions. However, this requires close personal contact, unprotected heterosexual or homosexual intercourse.

- Parenteral: It is the major route of transmission but occasionally nonparenteral.

Incubation period: 30–180 days (mean, 8–12 weeks) Chronic carrier state can develop with HBV infection (1–20%).

Prevention and Prophylaxis:

Question 20. Write short on prevention and prophylaxis of HBV.

Answer:

- Avoiding risk factors:

- Not to sharing of needles

- Having safe sex

- Transfuse safe blood and blood products

- Enforced strict standard safety precautions in laboratories and hospitals to avoid accidental needle punctures and contact with infected body fluids

- Active immunization: By using recombinant vaccines (containing HBsAg). It is advised in following individuals:

- Children: In India, nonpercutaneous routes of transmission are quite prevalent and active immunization using vaccine is recommended in all children.

- High-risk groups: For example, healthcare personnel, hemodialysis patients, injection drug users, hemophiliacs and sexual contacts of HBsAg carriers.

- Dosage regimen: Three injections are given into the deltoid muscle at 0, 1, and 6 months. Dose is 10 µg for children under 10 years and 20 µg in children above 10 years. More frequent and larger doses are required in individuals over 50 years of age or clinically ill and/or immunocompromised (including HIV infection or AIDS). Side-effects are very few.

- Combined prophylaxis: This consists of vaccination and immunoglobulin. It should be given to individuals with:

- Accidental needle-stick injury, gross personal contamination with infected blood and exposure to infected blood in the presence of cuts and grazes

- All newborn babies of HBsAg-positive mothers

- Regular sexual partners of HBsAg-positive patients, who have been found to be HBV negative

- Dosage: For adults, a dose 0.05–0.07 mL/kg bodyweight hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) (200 IU to newborns) and the vaccine (IM) given at another site.

Mode of Transmission Treatment: Pegylated interferon alpha, lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, or tenofovir may be used as initial therapy but lamivudine and telbivudine are not preferred because of high rates of resistance.

Hepatitis C:

Hepatitis C Etiology:

- Previously called bloodborne non-A, non-B hepatitis.

- It is a small, enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the family Flaviviridae.

- A characteristic feature is emergence of an endogenous, newly mutated strain. Because of genomic instability and antigenic variability, producing an effective HCV vaccine is difficult.

- HCV has six genotypes and in India, most prevalent is HCV

- Mode of spread: HCV is not transmitted by breastfeeding.

- It is mainly transmitted by the parenteral route (transfusion of blood and blood products, and in drug addicts) as a bloodborne infection

- Sexual contact (low chances of transmissio

- Perinatal/vertical transmission

- Incubation period: 15–160 days (mean, 7 weeks):

- Nearly 80% infected individuals develop chronic hepatitis.

Hepatitis D:

Question 21. Write short note/essay on etiology and epidemiology of delta hepatitis.

Answer:

Hepatitis D Etiology:

- Caused by hepatitis D virus (HDV or delta virus), which is a defective/incomplete RNA virus and belongs to the Deltaviridae family. The RNA genome is covered by an outer coat/shell of HBsAg.

- It has no independent existence and requires HBV for its replication and expression.

- Because HDV is dependent on HBV, the duration of HDV infection is determined by the duration of HBV infection. It causes delta hepatitis (Hepatitis D) with two clinical patterns.

- Acute coinfection: It develops when individual is exposed simultaneously to serum, containing both HDV and HBV. The HBV infection first becomes established and the HBsAg is necessary for development of complete HDV virions.

- Superinfection: It occurs when an individual is already infected with HBV (chronic carrier of HBV) is exposed to a

new dose HDV.

- Mode of spread: Parenteral route and sexual contact.

- Fulminant hepatitis can follow both patterns of infection but is more common after coinfection.

Hepatitis E:

Question 22. Write short note/essay on transmission, clinical features, and management of hepatitis E infection.

Answer:

It was previously called epidemic or enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis.

Hepatitis E Etiology:

- Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is an unenveloped, single-stranded RNA virus in the Hepevirus genus.

- Viral particles are 32–34 nm in diameter.

- Hepatitis E occurs primarily in young to middle-aged adults.

- Source of infection: HEV is a zoonotic disease with animal reservoirs, such as monkeys, cats, pigs, rodents, and dogs.

- Virions are shed in stool during the acute illness.

- Mode of transmission: An enterically transmitted, waterborne infection. It is common after contamination of water supplies such as after monsoon flooding.

- Incubation period: 14–60 days (mean, 5–6 weeks).

Outcome of Infection:

- HEV infection is responsible for more than 30–60% of cases of sporadic acute hepatitis (clinically very similar to hepatitis A) in India. It produces self-limiting acute hepatitis.

- It does not cause chronic liver disease.

- High mortality rate (about 20%) among pregnant women.

Prevention and Control:

- Good sanitation and hygiene similar to hepatitis A

- Vaccine has been developed and used successfully in China.

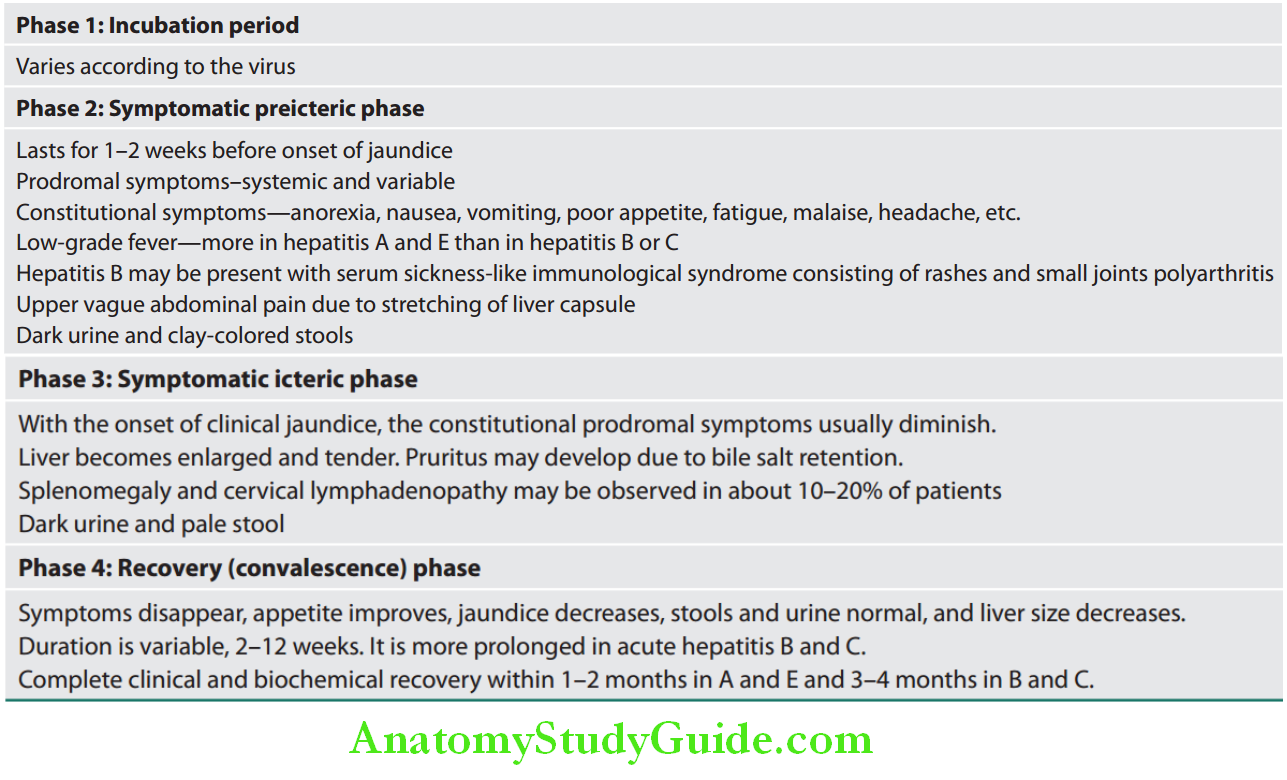

Clinical Features of Viral Hepatitis:

Question 23. Write short note/essay on clinical features of acute hepatitis/hepatitis A/hepatitis B.

Answer:

Fulminant Hepatitis:

It can develop in hepatitis B, D, and E. It is uncommon with hepatitis C and rare in hepatitis A. With hepatitis E, fulminant hepatitis occurs in nearly 20% cases in pregnant females.

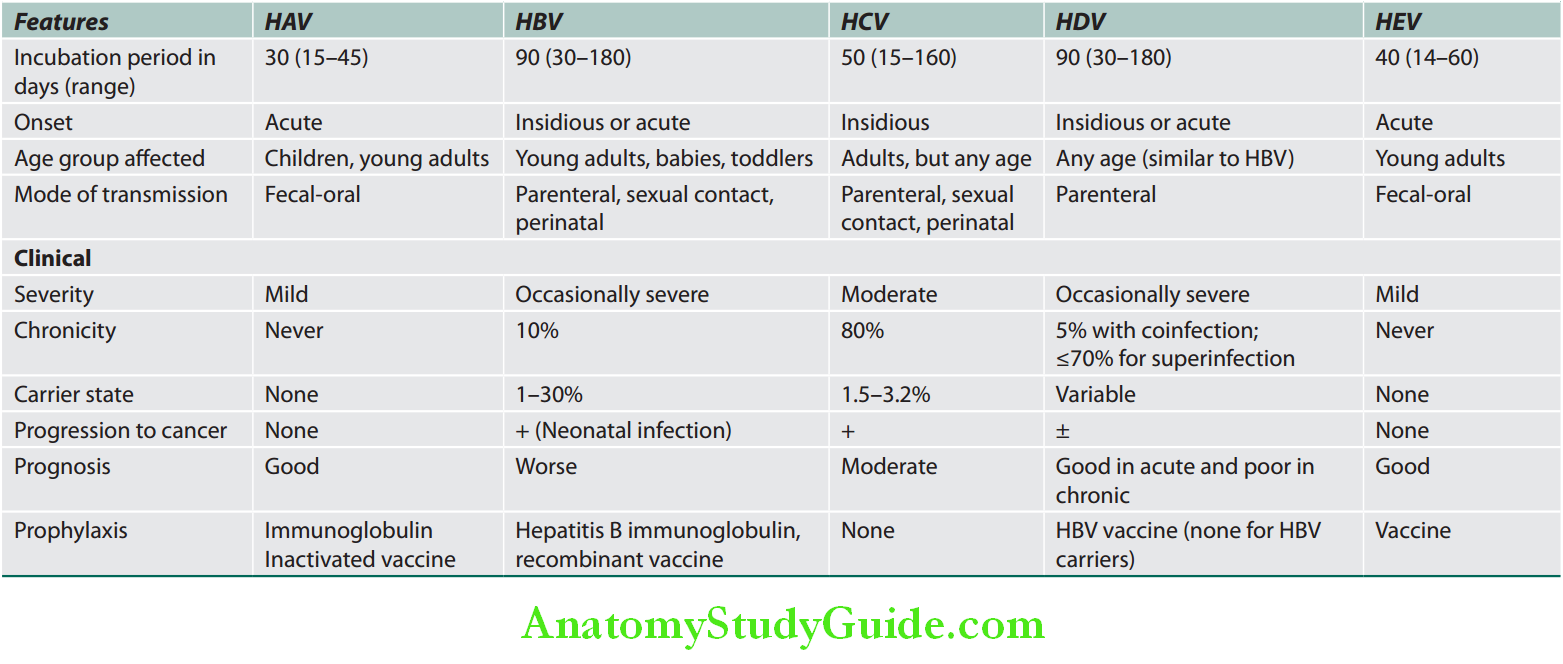

Summary of various hepatotropic viruses are presented in Table:

Summary of various hepatotropic viruses:

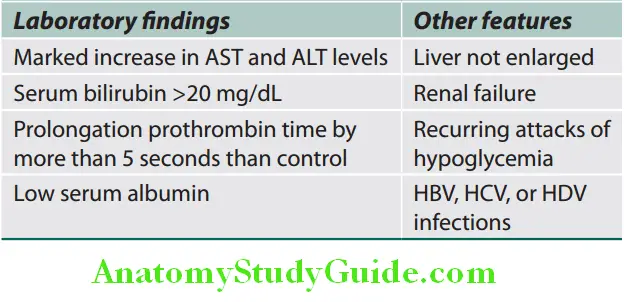

Fulminant Hepatitis Investigations:

- Urine:

- Bilirubinuria (in early stages) and increased urinary urobilinogen slight microscopic hematuria and mild proteinuria

- Hematological tests:

- Leukopenia with a relative lymphocytosis

- Prothrombin time (PT) is prolonged in severe cases which signifies extensive hepatocellular damage. This is one of the best indices of prognosis.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is raised

- Biochemical investigations

- Aminotransferases (AST, ALT): Raised and maximum levels are observed during the prodromal phase (400–4,000 IU/L). They progressively decline during icteric and recovery phases.

- Bilirubin: Both conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin levels are equally raised.

- ALP: It may be raised but usually less than two times the normal.

- Serum protein: Normal

- Blood glucose: It may below.

- Serological tests: During prodromal phase, low titers of antismooth muscle antibody, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, and heterophil antibody may be observed.

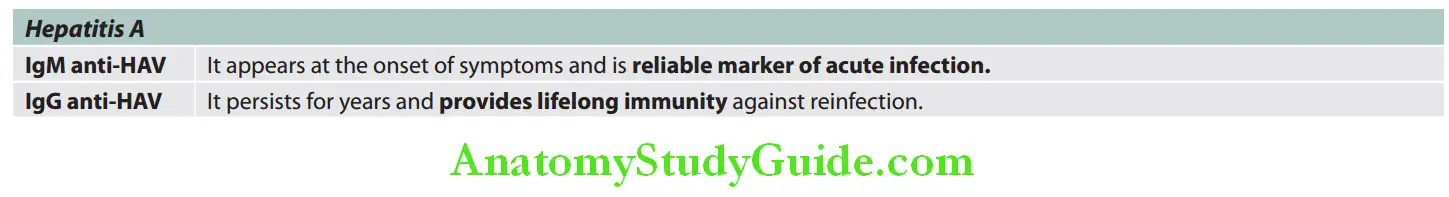

Serological Markers for Viral Hepatitis:

Question 24. Write short note on HBsAg/Australia antigen/hepatitis B surface antigen.

Answer:

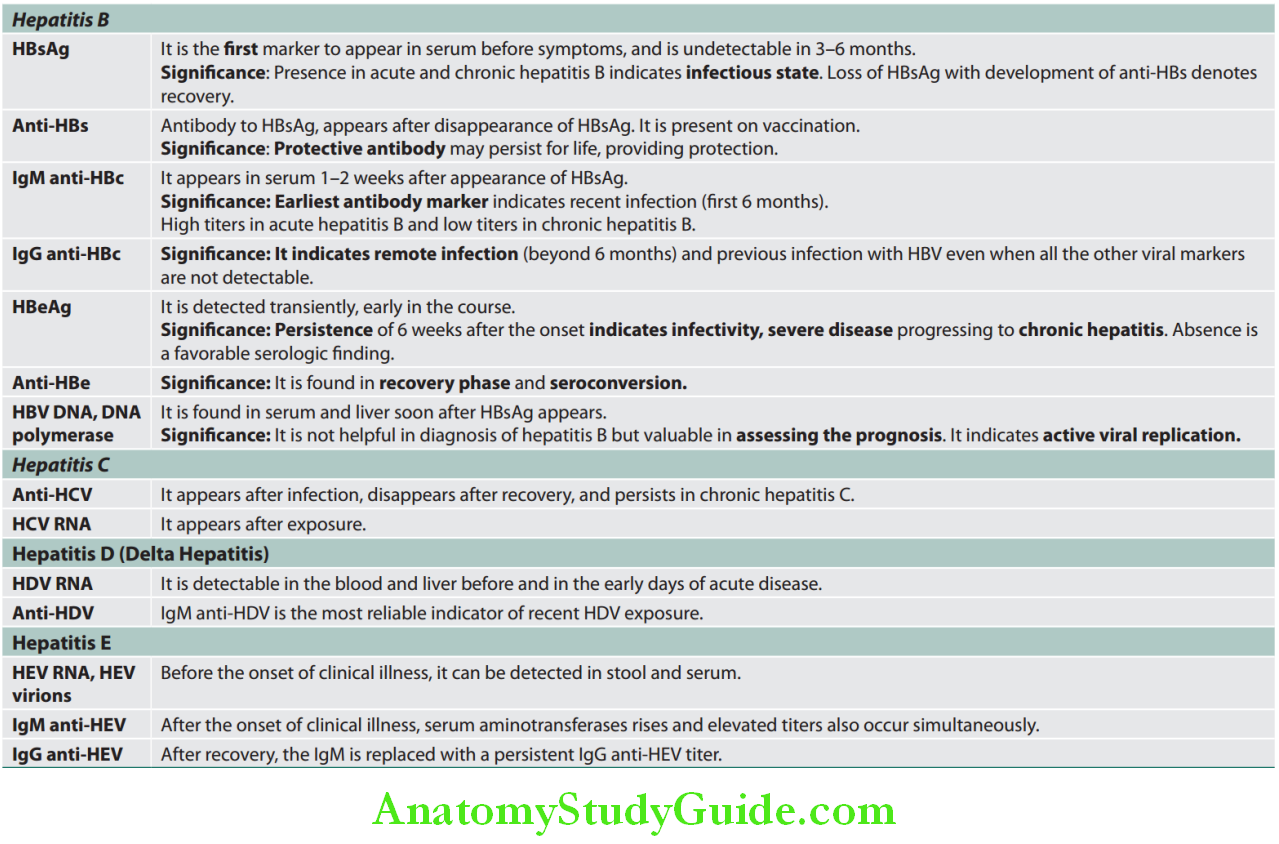

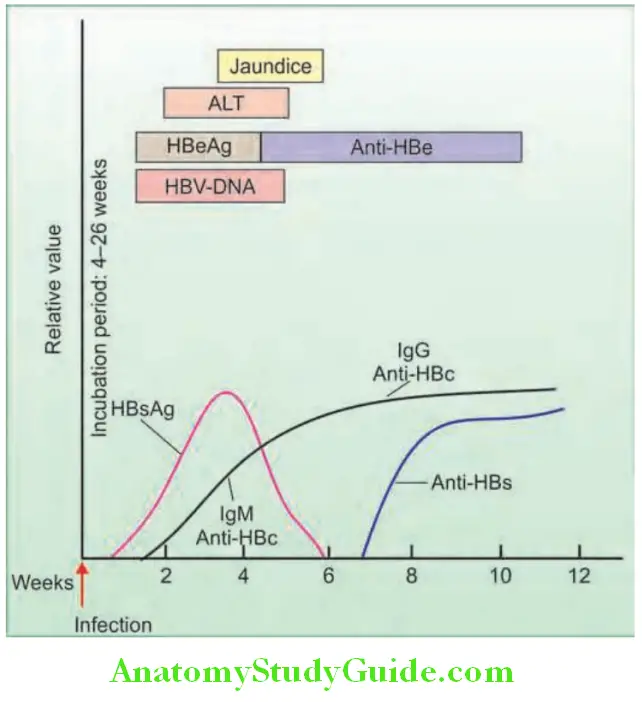

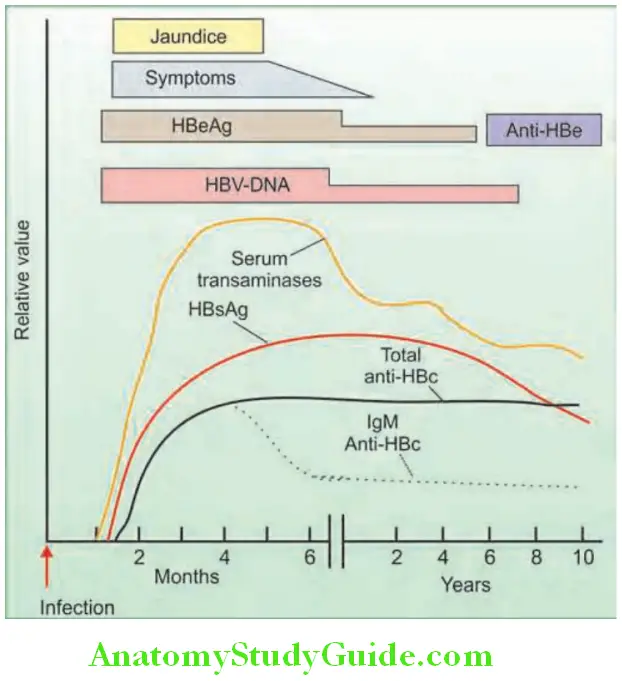

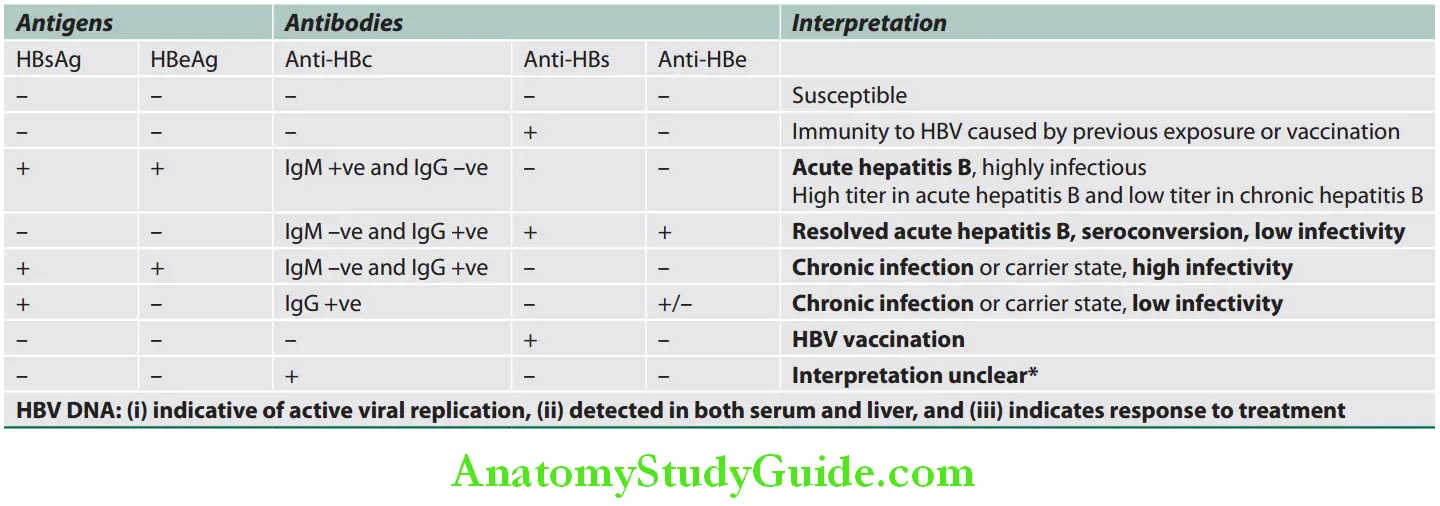

Interpretations of serological findings and its significance in HBV are summarized in Table:

HBV viral DNA (HBV DNA): Most accurate marker of virus replication:

Interpretation of serological fidings and its signifiance in HBV:

Question 25. Write short note on complications of acute viral hepatitis.

Answer:

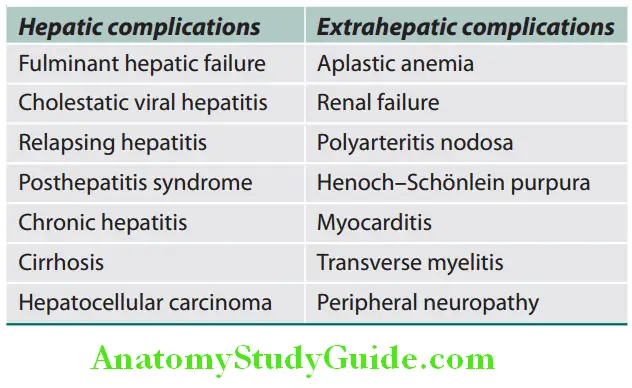

Complications of Acute Viral Hepatitis:

Hepatitis C:

- Anti-HCV: It appears after the infection, disappears after the recovery, and persists in chronic hepatitis C.

- HCV-RNA: It appears after the exposure.

- Anti-HCV (antibodies against HCV) does not confer immunity.

Hepatitis D:

- HDV RNA: Detectable in the blood and liver before and in the early days of acute disease.

- Anti-HDV: IgM anti-HDV is the most reliable indicator of recent HDV exposure.

Hepatitis E:

- Before the onset of clinical illness, HEV RNA and HEV virions can be detected in stool and serum.

- After the onset of clinical illness, serum aminotransferases rise and elevated IgM anti-HEV titers also occur simultaneously. After recovery, the IgM is replaced with a persistent IgG anti-HEV titer.

- Poor prognostic features of viral hepatitis are listed in Table:

Acute Viral Hepatitis Treatment:

General Measures:

- Avoid drugs which are metabolized in the liver, e.g., sedatives and narcotics.

- Avoid alcohol during the acute illness.

- No specific dietary modifications are required.

- Elective surgery should be avoided during acute viral hepatitis, as there is a risk of postoperative liver failure.

- Liver transplantation is performed for complications of cirrhosis resulting from chronic hepatitis B and C infection.

Hepatitis A:

Question 26. Write short note on treatment of hepatitis A infection.

Answer:

- No specific treatment:

- Rest and dietary measures are not helpful.

- Supportive symptomatic treatment

- Corticosteroids do not have benefit.

Hepatitis B:

Question 27. Write short note on treatment of hepatitis B infection.

Answer:

Therapeutic goal:

- It prevents the progression to end-stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and death with improvement in quality of life.

- Clearance of HBV DNA

- Absence of HBeAg and HBsAg and appearance of antibody

- Normalization of liver enzymes and histology

Acute Hepatitis B:

- In previously healthy adults, recovery occurs in ~99%; therefore, antiviral therapy is not required.

- Mainly symptomatic.

- Monitor HBV markers.

- Entecavir (ETV) or tenofovir (TDF) to be given when HBeAg persists beyond 12 weeks, and in patients who are very ill.

Postexposure Prophylaxis to Prevent Hepatitis B Virus Infection:

Hepatitis C:

- Goals of treatment of HCV:

- Eradication Of Virus,

- Reduce Progression Of Disease,

- Histological Improvement

- Decrease frequency of HCC.

- Interferon-∝ is used in acute hepatitis C to prevent chronic disease.

- HCV: Progression of fibrosis determines the prognosis and liver biopsy is the gold standard to assess fibrosis.

Hepatitis D:

Active liver disease (raised ALT levels and/or inflammation on biopsy) is treated with peginterferon ∝-2a and adefovir for 12 months.

Transfusion-associated Hepatitis (TAH):

- It includes HCV and/or HBV (discussed above).

Chronic Hepatitis:

Question 28. Discuss the classification, etiology, pathology, clinical features, complications, prevention, and management of chronic hepatitis/chronic hepatitis B infection.

(or)

Write short essay on chronic active hepatitis.

Answer:

Chronic Hepatitis Definition:

Chronic hepatitis is defined as symptomatic, biochemical, or serologic evidence of hepatic disease for more than 6 months. Microscopically, there should be inflammation and necrosis in the liver.

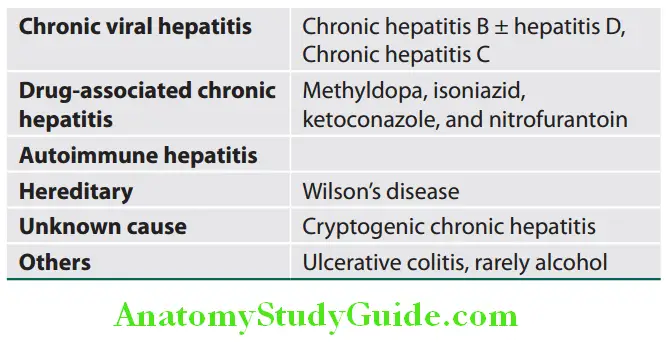

Chronic Hepatitis Classification:

Older classification: Previously chronic hepatitis was classified into:

- Milder forms:

- Chronic persistent hepatitis (CPH)

- chronic lobular hepatitis (CLH)

- Severe forms: Chronic active hepatitis (CAH)

However, this classification is not very helpful in determining the prognosis.

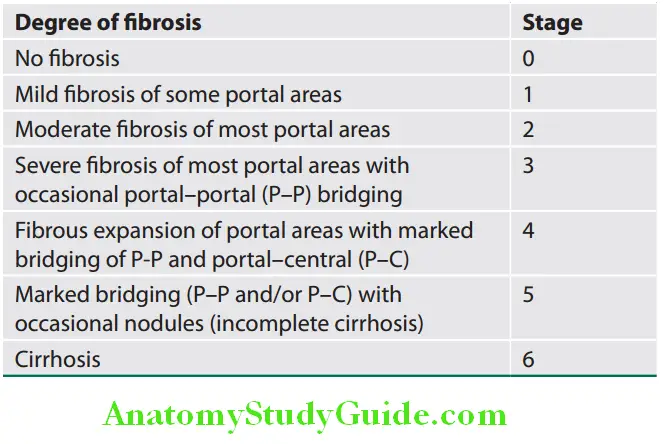

Present classification: In order to assess response to therapy and prognosis, present classification is based on combination of three factors.

Basis of present classification of chronic hepatitis:

- Etiology: Cause of hepatitis

- Grade: Histologic activity

- Stage: Degree of progression

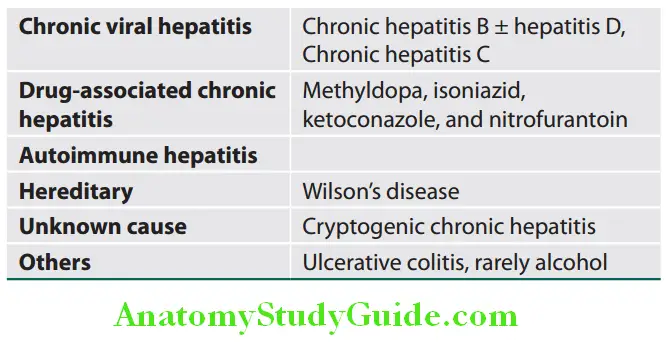

Classification Based on the Causes of Chronic Hepatitis:

It indicates level of progression and based on the degree of hepatic fibrosis

Autoimmune Hepatitis:

Question 29. Write short note on clinical features and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis.

Answer:

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic and progressive (unresolving) hepatitis of unknown cause. No features are absolutely diagnostic and are associated with circulating autoantibodies and hypergammaglobulinemia.

Autoimmune Hepatitis Clinical Features:

- It may be asymptomatic or present with fatigue (most common), anorexia, jaundice, myalgia, and diarrhea.

- Acute hepatitis: In about 30% of cases, it may present as acute hepatitis similar to viral hepatitis, which does not resolve with time.

- Fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) or asymptomatic elevation of serum ALT.

- Cirrhosis: In about 25% patients.

- Jaundice may be mild to moderate and is found in 69% of patients.

Autoimmune Hepatitis Investigations:

Biochemical findings:

- Serum aminotransferases: High and more than 10 times during relapses

- Serum bilirubin: Mildly raised usually less than 6 mg/dL

- Serum ALP: Mildly raised

- Serum γ-globulins: High; hypergammaglobulinemia is polyclonal; the IgG fraction predominates.

- Serum albumin: Low

- Serum al-antitrypsin, serum ceruloplasmin, iron and ferritin levels: Normal.

Autoantibodies:

Classification of autoimmune hepatitis based on immunological markers and autoantibodies is presented.

Classification of autoimmune hepatitis based on immunological markers:

Based on the differences in immunological markers AIH is divided into:

- Type 1 AIH is characterized by anti-smooth muscle antibodies (SMAs) and antinuclear antibodies (ANA), or both. Most commonly seen in females and associated with extrahepatic immunologic diseases such as autoimmune thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia.

- Type 2 AIH is characterized by antibodies to liver/ kidney microsome type 1 (anti-LKM1). Most affected persons are children.

- Type 3 AIH: Presence of antibodies to soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas (anti-SLP/LP)

Autoantibodies Other tests:

- HBsAg and other viral markers: Negative

- Prothrombin time: Prolonged

Liver biopsy:

Chronic hepatitis, variable amounts of interface hepatitis, Cirrhosis, bridging necrosis

Autoantibodies Treatment:

- Prednisolone: 30 mg given orally daily for 2 weeks. Gradually tapering dose as LFT improves. Maintenance dose of 10–15 mg daily for at least 2 years after LFT has become normal.

- Azathioprine: Dose of 1–2 mg/kg daily, added as a steroid-sparing agent and some patients for sole long-term maintenance therapy or if dose of prednisolone is more than 10 mg/day.

- Other immunosuppressive agents: Mycophenolate, ciclosporin and tacrolimus for resistant cases.

- Duration of treatment: Lifelong in most cases

- Liver transplantation: If treatment fails

Course and Prognosis:

- Exacerbations and remissions are common. Progression of steroid and azathioprine therapy produces remission in over 80% of patients.

- It may progress to hepatic failure and death.

- Some may develop cirrhosis and its complications.

- Hepatocellular carcinoma is uncommon.

Chronic Hepatitis B:

Question 30. Write short note on complications of HBV infection.

Answer:

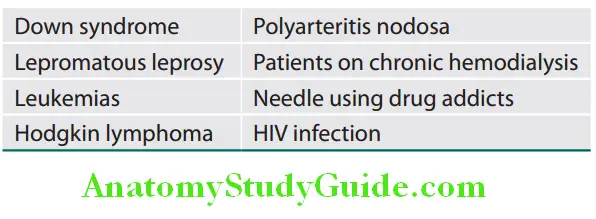

- Chronic HBV infection occurs following an acute HBV infection (may be subclinical) and occurs in about 1–10% of patients.

- HBV infection is considered as chronic when the HBsAg (hepatitis B surface antigen) persists for more than 6 months.

- It may progress to cirrhosis and HCC.

- Risk of chronic hepatitis Depends on:

- Age at which the contact of acute infection: Chronic hepatitis occurs more commonly with neonatal (90%) or childhood (20–50% below the age of 5 years) infection rather than in adult life (<10%).

- Immune status: In immunocompetent adults, the incidence of acute hepatitis is high while chronic infection is rare (1–2% of cases).

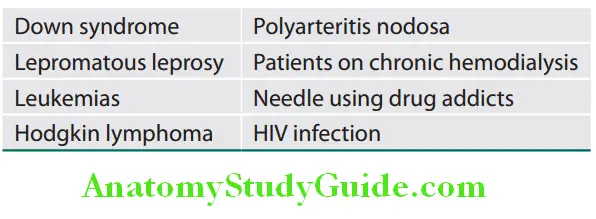

Other conditions where incidence of chronic hepatitis B infection is high are given in Table:

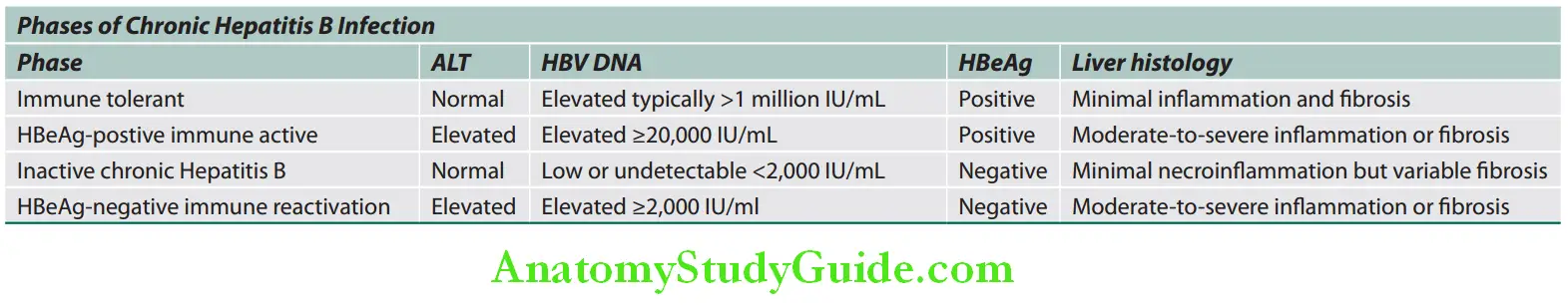

Phases of Chronic HBV Infection:

1. Immune-tolerant phase Characteristic features are:

- Asymptomatic and frequent in children. Infection during birth or in early childhood develop prolonged immune-tolerant phase, and disease progresses even after the disappearance of HBeAg in some of these patients.

- Active viral replication in liver but little or no evidence of disease activity.

- HBsAg and HBeAg positive and very high levels of serum HBV DNA.

- Normal LFTs

- Liver biopsy shows no inflammation or fibrosis.

- It may lasts for decades. Therefore, lifelong monitoring is necessary.

2. Immune-active phase (chronic hepatitis): Most patients with immune-tolerant phase progress to the immune-active phase.

- Vigorous immune response.

- Criteria for chronic HBV active hepatitis are:

- Liver biopsy shows chronic hepatitis with moderate or severe necroinflammation and fibrosis.

- Evidence of active HBV replication: High levels of HBV DNA and HBeAg

- Persistent or intermittent elevation of serum aminotransferases (ALT/AST)

3. Inactive chronic Hepatitis B—carrier phase with low replication: Incidence varies. Most patients with chronic HBV infection will eventually enter inactive carrier phase.

- Criteria for carrier phase:

- Serological findings:

- HBsAg positive in the serum > 6 months.

- HBeAg negative and HBe antibody positive (seroconversion from HBeAg to HBeAb).

- Undetectable or low levels (below 400 IU/L) of HBV DNA in the serum.

- Normal aminotransferase (ALT) levels.

- Liver biopsy does not show any significant hepatitis.

- Low-risk for hepatocellular carcinoma

- Liver abnormalities generally do not progress to more severe disease.

- Disease may be reactivated by severe immunosuppression (e.g., during chemotherapy for cancer or with bone marrow transplantation).

Individuals infected during adults or adolescence usually become inactive carriers after they clear HBeAg.

4. Chronic HBeAg-negative immune reactivation:

- Patients harbor HBV variants with mutations that prevent production or have low HBeAg.

- HBV DNA levels are high, liver enzymes are raised, and active histological activity is present.

- Late phase in the natural history of chronic HBV and often seen in older patients with advanced disease

HBV genotype C infection (prevalent in India) has an increased chance of developing cirrhosis and HCC.

Chronic HBV Infection Clinical Features:

- Asymptomatic or may develop severe end-stage liver disease.

- Symptoms: Fatigue, malaise, and anorexia, persistent or intermittent jaundice.

- During end-stage liver disease: Symptoms due to complications of cirrhosis occur.

- Extrahepatic manifestations: Arthralgias, arthritis, vasculitis, glomerulonephritis, and polyarthritis nodosa.

- Mild hepatomegaly

- Long-standing cases may develop HCC.

Chronic HBV Infection Investigations:

Biochemical investigations:

- Serum aminotransferase: Mildly elevated but may be as high as 1,000 units. ALT (SGPT) tends to be more raised than

compared to AST (SGOT). Once cirrhosis develops, AST levels exceeds ALT. - Serum bilirubin: It may be normal or raised up to 10 mg/dL.

- Serum proteins: Hypoalbuminemia in severe cases and hyperglobulinemia

Prothrombin time: Prolonged

Serological markers:

Serological markers of chronic hepatitis B:

- Positive HBsAg

- Positive IgG anti-HBc, negative IgM anti-HBc

- Positive HBe antigen or rarely, positive anti-HBe

- Positive HBV DNA

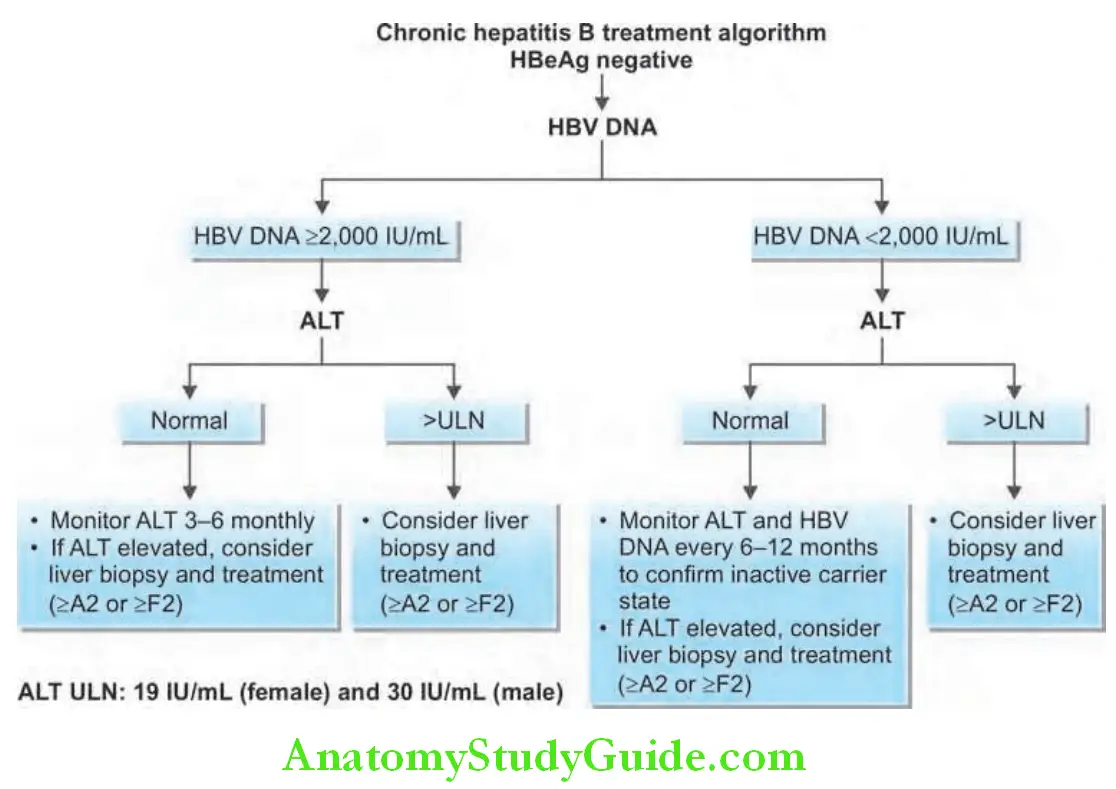

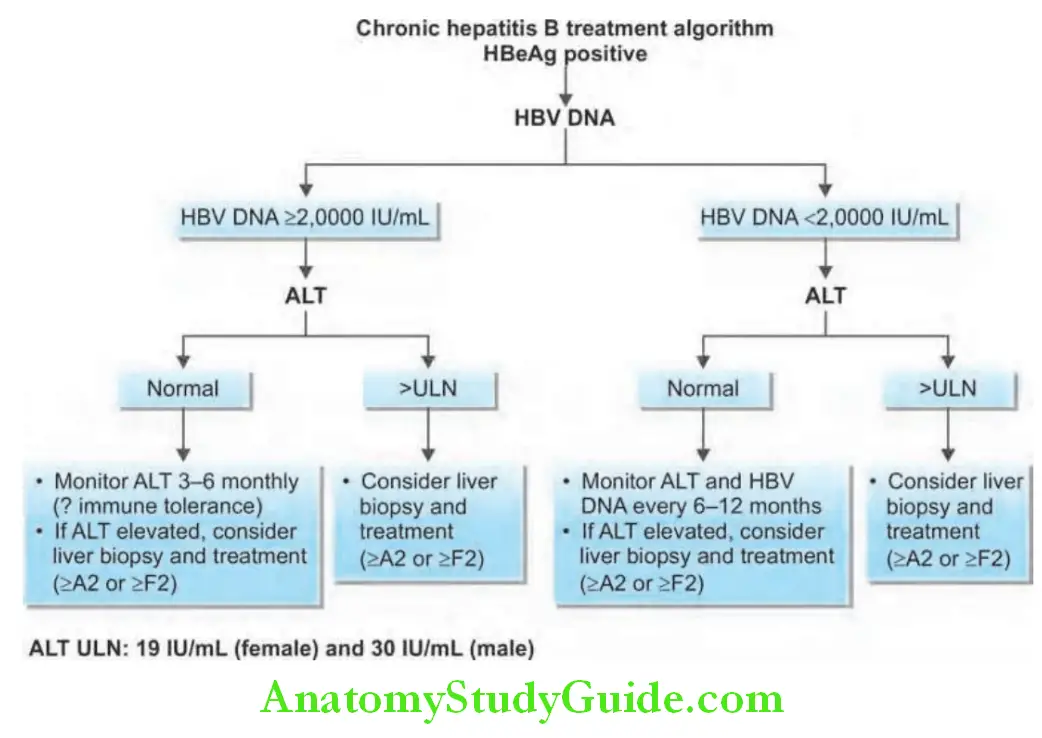

Treatment for Chronic Hepatitis B:

Criteria: Three criteria are used namely: serum levels of HBV DNA, serum levels of ALT, and histological grade and stage.

- Serum HBV DNA above 2000 IU/mL (about >10,000 copies/mL)

- Serum ALT level greater than two times the normal

- Moderate-to-severe active necroinflammation and/or fibrosis in the liver biopsy

In presence of cirrhosis (compensated or decompensated), oral antiviral agents are recommended but liver transplantation may be necessary.

Patients without cirrhosis: Pegylated interferon, tenofovir, and entecavir are the preferred agents in patients with clinically compensated cirrhosis, entecavir or tenofovir (tenofovir alafenamide or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) is preferred.

For patients with decompensated cirrhosis, interferon is contraindicated, and either entecavir or tenofovir should be used.

Immunotolerant patients, usually young with normal ALT and high HBV DNA levels, without evidence of liver disease do not need therapy, but be regularly followed-up.

Aim of treatment:

Aim of treatment of chronic hepatitis B:

- Seroconversion of HBeAg when present to anti-HBe. When HBeAg disappears, remission is usually attained for several years.

- Reduction of HBV DNA to 400 IU/L or less.

- Achieve normal levels of serum ALT.

- Histological improvement in inflammation and fibrosis in the liver biopsy

- Patients usually remain HBsAg positive, but loss of serum HBsAg indicates a good response.

Antiviral agents:

Most commonly used drugs are:

Drugs used for chronic hepatitis B:

- Peginterferon in combination with other agents:

- Lamivudine plus peginterferon

- Entecavir plus peginterferon

- Tenofovir plus peginterferon

- Adefovir plus peginterferon

- Telbivudine plus peginterferon

- Lamivudine plus adefovir dipivoxil

- Tenofovir disoproxil plus entecavir

- Tenofovir disoproxil plus emtricitabine

Pegylated α-2a interferon:

- Response (defined as loss of HBeAg and HBV DNA) occurs in 25–40% of cases.

- Dose: 180 μg once a week subcutaneously and produces response after 48 weeks of treatment.

- Side effects: Acute flu-like symptoms, malaise, headache, depression, reversible hair loss, bone marrow depression, thrombocytopenia, and infection

- Patients with HIV respond poorly and it should not be given to patient with cirrhosis.

Entecavir:

- A cyclopentyl guanosine analog that is a very effective and quickly reduces HBV DNA by 48 weeks.

- 0.5–1 mg daily

Tenofovir:

- It is a cytosine nucleoside analog which is also very effective and has a similar potency to entecavir. It is used for HIV patients with HBV infection.

- Tenofovir alafenamide (25 mg daily) OR tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (300 mg daily)

Lamivudine:

- It is well tolerated. However, rate of development of viral resistance (80%) is high and itself may cause hepatitis. Hence, lamivudine monotherapy is no longer recommended.

- Dosage is 100 mg/day given orally once a day until HBeAg becomes negative.

- Used if coinfection with HIV

Adefovir dipivoxil:

- A nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

- 10 mg daily is used in treatment of patients with lamivudine-resistant HBV

Telbivudine:

- An L-nucleoside that may cause myopathy and neuropathy.

- The recommended dose is 600 mg once daily

Chronic HBV Infection Prognosis:

- Development of chronic hepatitis depends on the age at which infection is acquired.

- Development of cirrhosis is associated with a poor prognosis.

- Hepatocellular carcinoma is one of the most common carcinomas in HBV-endemic areas.

Chronic Hepatitis C:

Question 31. Write short note on complications of HCV.

Answer:

- Chronic hepatitis occurs in the majority (70–85%) of individuals infected by HCV and is the hallmark of HCV infection.

- Cirrhosis develops over 5–20 years in 20–30% of patients, while HCC also develops in several patients, especially with cirrhosis.

- Factors that accelerate progression to advanced liver disease includes: Alcohol consumption, coinfection with HIV or HBV, and older age at the time of acquiring the infection.

Chronic Hepatitis C Clinical Features:

- Usually asymptomatic. Detected following a routine biochemical test when mild elevations in the aminotransferases (usually ALT) are detected.

- Clinical features when present are similar to chronic hepatitis B. Most common being fatigue and jaundice being rare.

- Extrahepatic features.

Chronic Hepatitis C Investigations:

- HCV antibody in the serum is detected in more than 95% cases.

- HCV RNA detectable in all patients

- Liver biopsy is performed if active treatment is being considered. The histological changes are highly variable. It most commonly shows features of chronic hepatitis, often with lymphoid follicles in the portal tracts, and fatty change.

- Other laboratory features are similar to those seen in chronic hepatitis B.

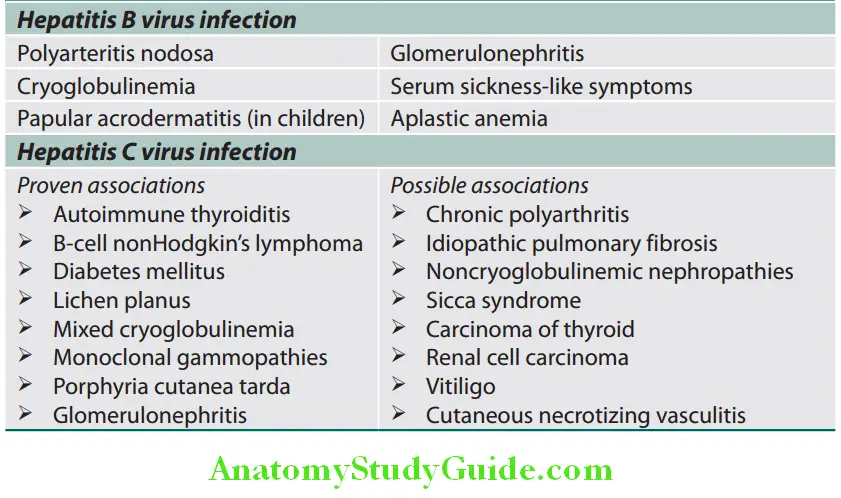

Extrahepatic Manifestations of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Virus Infection:

Extrahepatic manifestations of B and hepatitis C virus infection:

Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C:

- Indications for treatment:

- Chronic hepatitis on liver histology with HCV RNA in the serum and raised serum aminotransferases for more than 6 months.

- Chronic hepatitis with persistently normal aminotransferases.

- Cirrhosis, fibrosis, or moderate inflammation on liver biopsy (biopsy not mandatory).

- The goal of antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) is to eradicate HCV RNA, which is predicted by attainment of a sustained virologic response (SVR), defined as an undetectable RNA level 12 weeks following the completion of therapy.

- Liver transplant: For patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

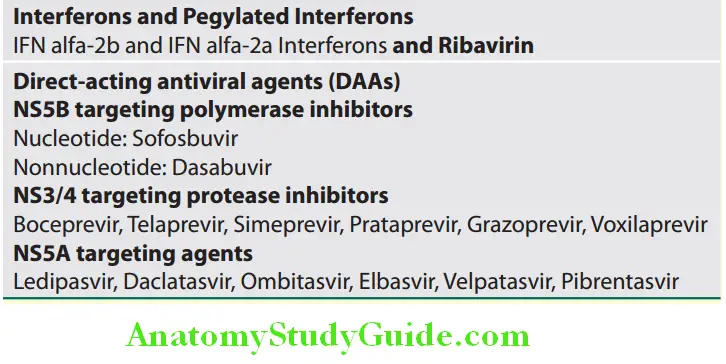

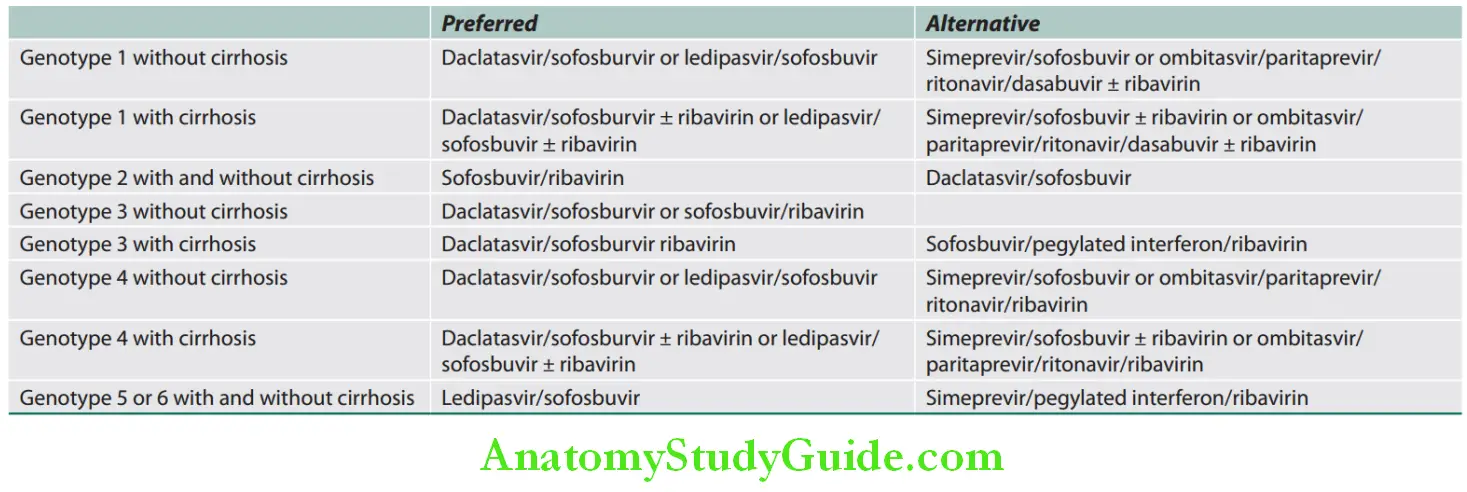

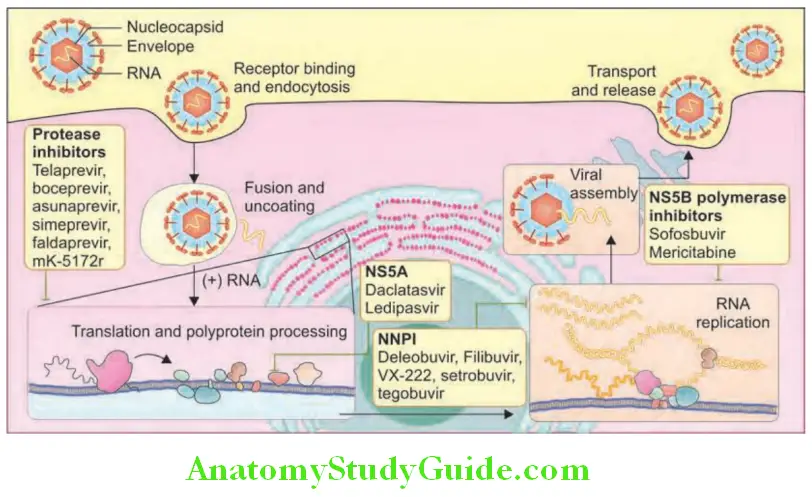

Drugs for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C:

Antivirals for HCV infection in treatment-naive patients:

Acute Liver Failure:

Question 32. Define fulminant hepatic failure. Discuss the causes, pathology, clinical features, investigations, complications, and management of fulminant hepatic failure.

(or)

Enumerate the precipitating causes of hepatic coma in a case of chronic liver disease. Discuss the diagnosis and treatment of hepatic coma.

Answer:

Acute Liver Failure Definition:

Acute liver failure is defined as the rapid progressive deterioration in the liver function, specifically coagulopathy [elevated prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (INR)] and mental status changes (encephalopathy) in a patient without known prior liver disease.

Classifiation of Acute Liver Failure:

Acute liver failure is subclassified into hyperacute, acute, and subacute, depending on the interval between onset of jaundice and encephalopathy.

- Hyperacute hepatic failure: If encephalopathy develops within 7 days, it is called hyperacute hepatic failure and has better prognosis than acute hepatic failure.

- Acute/FHF: In this, encephalopathy develops within 3 weeks (7–21 days) from onset of symptoms in a patient with a previously normal liver.

- Subacute hepatic failure: If hepatic failure develops at a slower pace (>21 days and <26 weeks), it is called subacute or subfulminant hepatic failure.

Fulminant Hepatic Failure:

It is defined as severe hepatic failure (insufficiency) in which encephalopathy develops within 8 weeks from onset of symptoms in a patient with a previously normal liver.

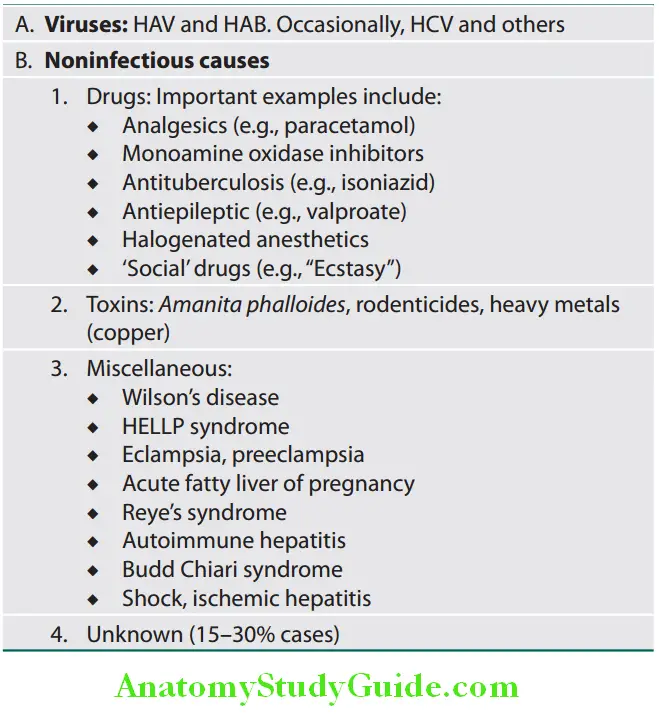

Acute Liver Failure Etiology: FHF is a rare but often life-threatening condition and the various causes of FHF are listed in Table

Important causes of fulminant hepatic failure:

Acute Liver Failure Clinical Features:

- General features:

- Jaundice, weakness, nausea, and vomiting

- Pain in the right hypochondrium

- Small liver and liver dullness are absent on percussion.

- Ascites and edema develop later.

- Features of hepatic encephalopathy:

- Mental state: It varies from mild drowsiness, confusion, and disorientation (grades I and II) to unresponsive coma (grade IV) with convulsions.

- Fetor hepaticus and flapping tremor (asterixis) is common.

- Ascites and splenomegaly are rare.

- Fever, vomiting, hypotension and hypoglycemia may be observed.

- Spasticity and extension of the arms and legs and plantar responses remain flexor until late.

- Features of cerebral edema: Cerebral edema develops in ~80% of patients.

- Bradycardia, intracranial hypertension, and irregular respiration (Cushing’s triad).

- Pupils: Unequal or abnormally reacting or fixed pupils

- Hyperventilation and hyperreflexia.

- Consequences: Intracranial hypertension and brain herniation are the most common causes of death.

Acute Liver Failure Investigations:

Investigations to determine the cause of acute liver failure:

- Serum findings:

- Hyperbilirubinemia: Serum bilirubin is raised.

- Serum aminotransferases are raised but are not useful indicators of the course of the disease as they tend to fall with progressive liver damage.

- Coagulation factors are decreased including prothrombin and factor V. Prothrombin time is prolonged.

- Serum proteins: Hypoalbuminemia

- Plasma and urine amino acids are increased.

- Blood ammonia levels: Raised.

- Urine shows protein, bilirubin, and urobilinogen.

- Peripheral blood: Leukocytosis and thrombocytopenia.

- EEG: It may be help in grading the encephalopathy.

- Ultrasound: To detect the liver size and for any evidence of underlying liver pathology

- CSF: Intracranial pressure is raised, but CSF is normal.

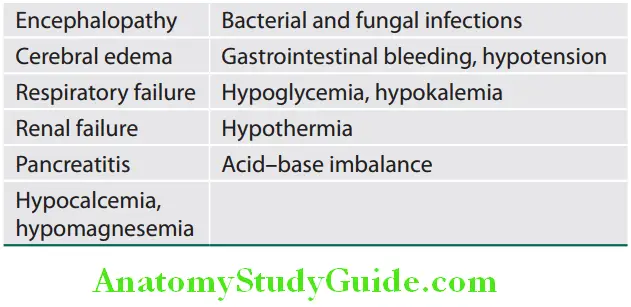

Complications of FHF are listed in Table:

Complications of fulminant hepatic failure:

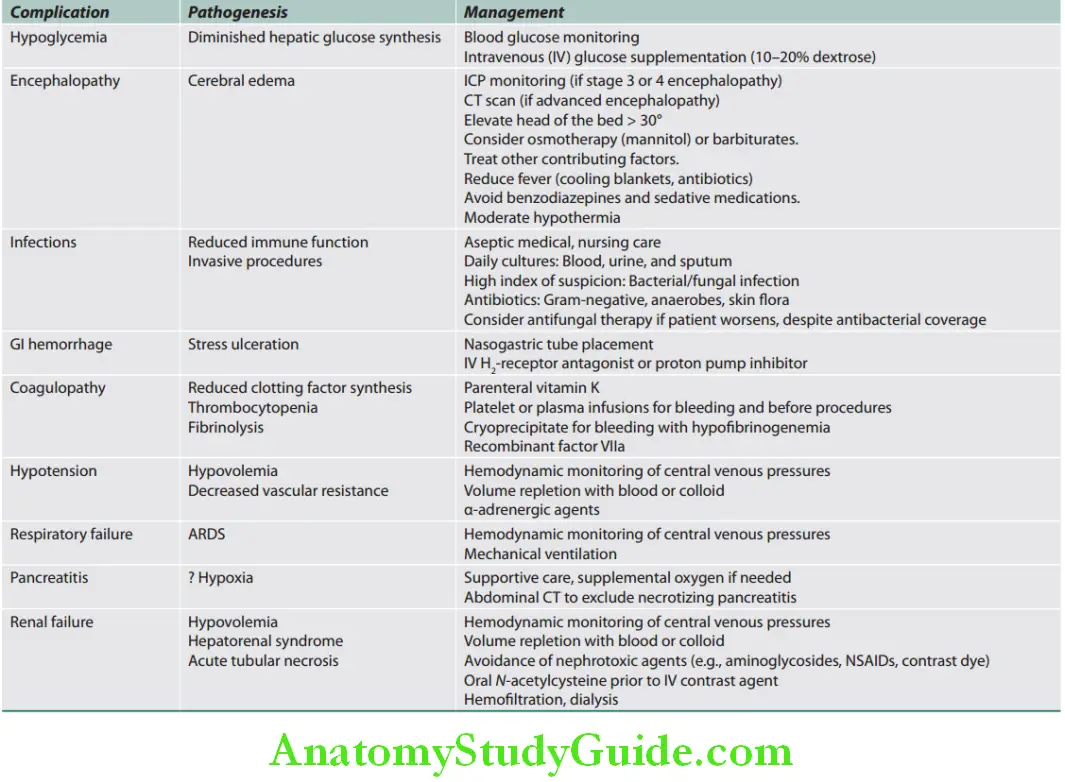

Pathogenesis and management of major complications of acute liver failure are given in Table:

Pathogenesis and management of major complications of acute liver failure:

Prognosis: The mortality is ~80% without liver transplantation, and ~35% with transplantation.

Reye’s Syndrome:

- Reye/Reye’s syndrome is a rapidly progressive encephalopathy with hepatic dysfunction, which begins several days after apparent recovery from a viral illness, especially varicella or influenza A or B. History of aspirin intake may be present.

- Liver shows severe fatty change.

- Raised ammonia levels and liver enzymes

- Usually no jaundice

Fatty Liver:

Question 33. List causes of fatty liver.

Answer:

Fatty liver (steatosis) is an abnormal accumulation of triglycerides within the cytosol of the parenchymal cells.

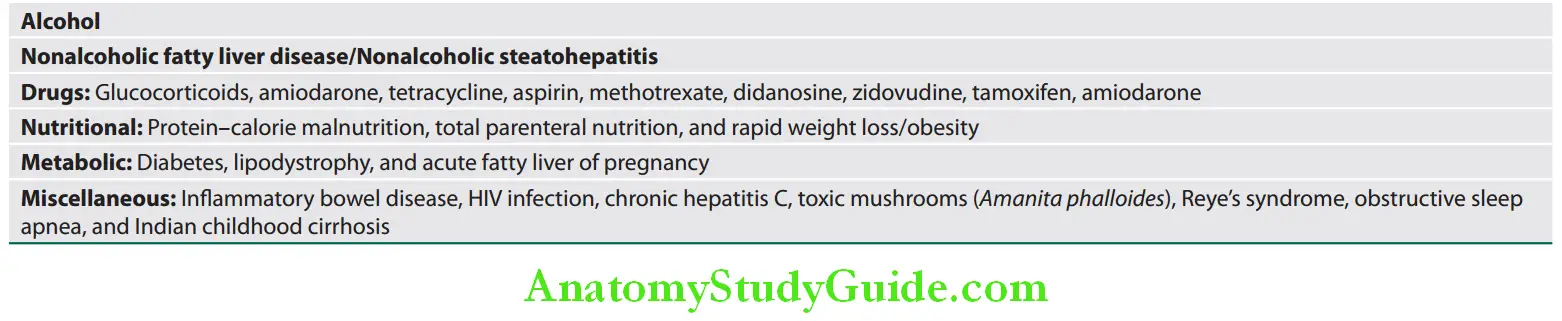

Causes of fatty liver:

Various causes of fatty liver:

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Nonalcoholic Steatosis and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis):

Question 34. Write short note on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Answer:

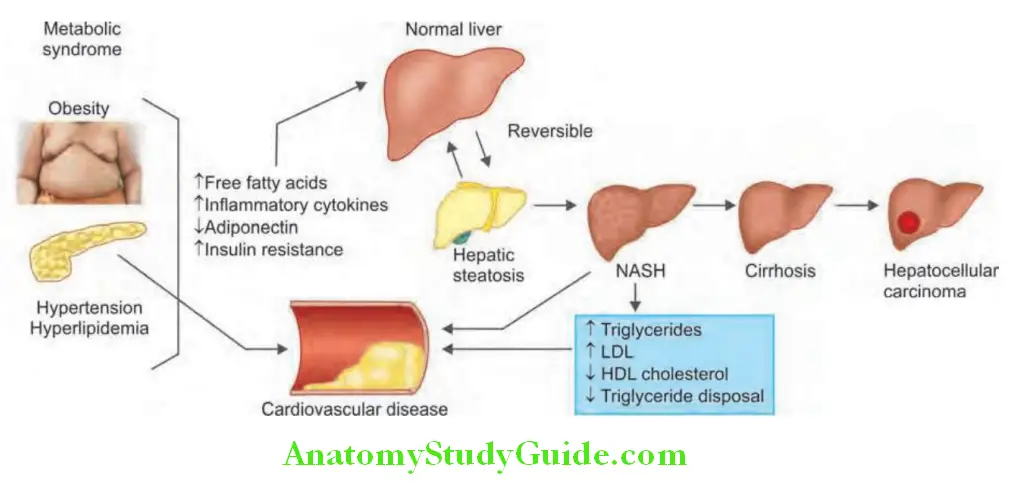

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a disease of affluent societies. Its prevalence increases in proportion to the rise in obesity. Its progression accounts for the majority of cryptogenic cirrhosis.

It is increasingly recognized condition and is the most common cause of chronic liver disease after hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and alcohol.

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Classifiation:

- Simple fatty liver disease with favorable prognosis

- Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) associated with fibrosis and progression to cirrhosis and sometimes to HCC.

Risk Factors for NAFLD:

Increased prevalence in those with the metabolic syndrome.

- Obesity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and insulin resistance.

- Rare causes: Tamoxifen, amiodarone and exposure to certain petrochemicals.

- Pathogenesis: NASH is induced by two consecutive steps: Excess fat accumulation and subsequent necroinflammation in the liver.

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Clinical Features:

- Most are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis and many patients are obese.

- Some have fatigue, malaise, and a sensation of fullness in the upper abdomen.

- Hepatomegaly is the only sign in most patients.

Diagnosis of NAFLD:

Patient with mild-to-moderately elevated serum transaminases, no history of alcohol abuse and a negative chronic liver disease screen.

Diagnosis of NAFLD Investigations:

- Mild elevation of serum aminotransferases is frequently the sole abnormality with AST: ALT < This ratio increases as fibrosis advances. It may be only isolated elevation of the GGT. ALP is elevated in about 30% of patients.

- The alcoholic liver disease to NAFLD index (ANI):

- ANI = -58.5 + 0.637 (MCV) + 91 (AST/ALT) 0.406 (BMI) + 6.35 for men

- An ANI greater than zero favors a diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease, whereas an ANI less than zero favors a diagnosis of NAFLD.

- Ferritin levels are increased in 20–50% of patients.

- Autoantibodies are found in about 25% patients with more advanced fibrosis.

- Ultrasound and CT features: Similar to those in alcoholic fatty liver

- Liver biopsy:

- Best diagnostic tool for confirmation and staging the disease.

- Microscopic changes are similar to those of alcohol-induced hepatic injury and range from simple fatty change to fat and inflammation (steatohepatitis) and fibrosis. NASH is characterized by fat, Mallory bodies, neutrophil infiltration, and pericellular fibrosis.

Diagnosis of NAFLD Management/Treatment:

- Weight loss, control of diabetes, and hyperlipidemia in the early stages

- Some drugs such as metformin, thiazolidinediones (e.g., pioglitazone), liraglutide, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), vitamin E, orlistat, obeticholic acid, aramchol, betaine, losartan pentoxipylline and atorvastatin have shown some promise.

- Liver transplantation is done for end-stage cirrhosis.

- Unfortunately, it may recur in the graft.

- Regular follow-up, particularly for steatohepatitis

Alcoholic Liver Disease:

List the types of alcoholic liver diseases. Discuss the clinical features and management of alcoholic hepatitis.

Chronic and excessive consumption of alcohol can produce a wide spectrum of liver disease which can be divided mainly into four major lesions:

- Fatty liver

- Alcoholic hepatitis

- Alcoholic cirrhosis (refer later)

- HCC

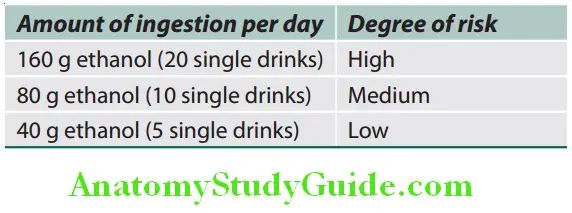

Threshold for alcohol and risk of alcoholic liver disease: Generally, the effects of alcohol are worse in women compared to men and amount of alcohol with degree of risk in male are presented in Table.

Amount of alcohol consumption and its associated risk of alcoholic liver disease in male:

For women, the above figures should be reduced by 50%. Alcohol by volume (ABV) of various alcoholic beverages.

Alcohol percentage content:

- Vodka | ABV: 40–95%

- Gin | ABV: 36–50%

- Rum | ABV: 36–50%

- Whiskey | ABV: 36–50%

- Tequila | ABV: 50–51%

- Liqueurs | ABV: 15%

- Fortified Wine | ABV: 16–24%

- Unfortified Wine | ABV: 14–16%

- Beer | ABV: 4–8%

- Malt beverage | ABV: 5–15%

Alcoholic Fatty Liver (Alcoholic Steatosis):

Diagnosis of NAFLD Clinical Features:

- It is asymptomatic.

- Occasionally, it may present with discomfort in right upper quadrant, nausea, and jaundice.

- Most common feature is hepatomegaly with or without tenderness.

- Progression to cirrhosis is not common with its associated complications.

Diagnosis of NAFLD Investigations:

- Biochemical findings:

- Moderately raised ALT and AST with AST: ALT >

- γ-GT level is a sensitive test to determine whether the individual is taking alcohol.

- Ultrasound: Diffuse increase in echogenicity

- CT scan: Fatty infiltration produces a low-density liver.

- Liver biopsy: It shows accumulation of fat in perivenular hepatocytes and later in entire hepatic lobule.

Diagnosis of NAFLD Treatment: Complete cessation of alcohol consumption and nutritional support results in normalization of biochemical findings and histological changes.

Alcoholic Hepatitis:

Diagnosis of NAFLD Clinical Features:

- It may be asymptomatic or present with fever, rapid onset of jaundice, abdominal discomfort, and proximal muscle wasting.

- Portal hypertension, spider nevi, ascites, and bleeding due to esophageal varices can occur without cirrhosis.

- Hepatomegaly (tender) and splenomegaly.

Diagnosis of NAFLD Investigations:

- Biochemical findings:

- Serum aminotransferase (AST and ALT) raised to 2–7 times of normal (usually < 400 IU)

- AST: ALT ratio is >1 (generally >2)

- Raised bilirubin

- Mildly elevated serum ALP

- Decreased albumin

- Hematological findings: Prolonged prothrombin time and leukocytosis.

- Liver biopsy: Ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes with leukocyte infiltration. Mallory bodies are often seen. They are potentially reversible but many progress to cirrhosis.

Diagnosis of NAFLD Prognosis:

- Variable and despite abstinence, the liver disease progresses in many patients. Conversely, a few patients continue to drink heavily without developing cirrhosis.

- Mortality is high in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.

- Poor prognostic factors .

Poor prognostic factors of alcoholic hepatitis:

- Prothrombin time >5 seconds of control

- Anemia

- Albumin <5 g/dL

- Serum bilirubin >8 mg/dL

- Progressive encephalopathy

- Renal failure

- Presence of ascites

- Maddrey’s discriminant function >3

Maddrey’s discriminant function (DF) = (6 x [prothrombin time (sec) − control prothrombin time (sec)]) + (serum bilirubin) The ABIC (age, bilirubin, INR, and creatinine) is a modification of the MELD score. An ABIC score >9 is associated with approximately 80% mortality at 90 days.

Diagnosis of NAFLD Treatment:

- It is advised to stop alcohol consumption for life, because this is a precirrhotic condition.

- Severe hepatitis needs bed rest.

- Nutrition: Feeding via a fine-bore nasogastric tube or sometimes intravenously (>3,000 kcal/day; multivitamins mainly vitamins B and C).

- Treatment for encephalopathy and ascites

- Corticosteroids (prednisolone) may be tried in severe cases (discriminant function > 32) in the absence of any infection.

- Antibiotics (pentoxifylline) in severe cases (discriminant function >32) and antifungal prophylaxis.

Cirrhosis:

Question 35. LIst the causes of cirrhosis. Discuss the pathology, pathogenesis, classification, clinical features, investigations, complications and treatment/management of cirrhosis.

(or)

Describe Laennec’s cirrhosis and alcoholic cirrhosis.

Answer:

Cirrhosis Defiition:

Cirrhosis is an end-stage of any chronic liver disease. It is a diffuse process (entire liver is involved) characterized by fibrosis and conversion of normal architecture to structurally abnormal regenerating nodules of liver cells.

The three main morphologic characteristics of cirrhosis are:

- Fibrosis

- Regenerating Nodules

- Loss of architecture of the entire liver.

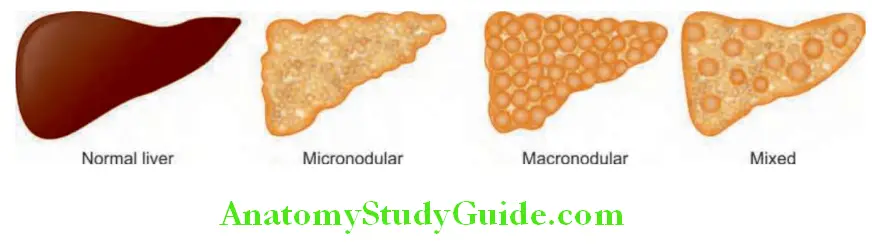

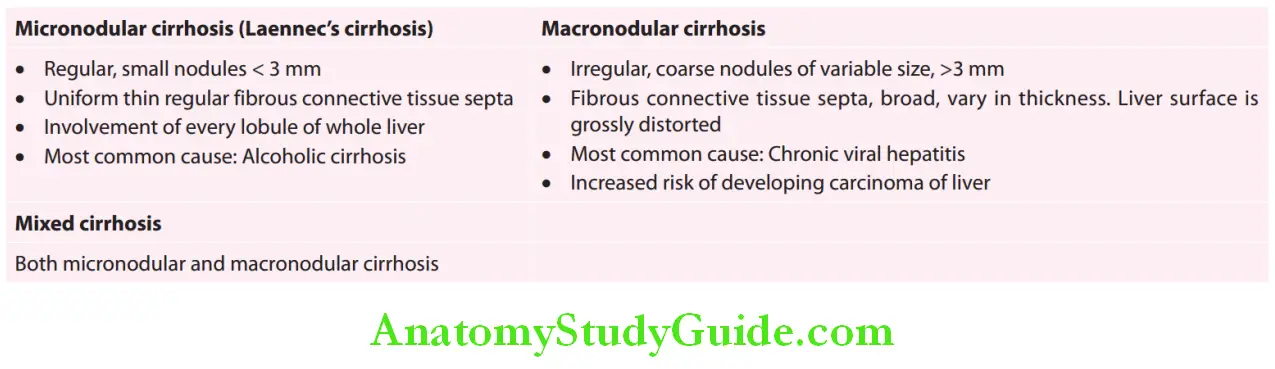

Cirrhosis Classifiation:

Morphological classification

Morphological classification of cirrhosis:

Cirrhosis Etiological Classifiation:

Main causes of cirrhosis:

- Alcohol (one of the most common causes)

- Chronic viral hepatitis (most common cause)

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Delta hepatitis (Hepatitis D) + Hepatitis B

- Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (earlier was considered as cryptogenic cirrhosis)

- Biliary cirrhosis

- Primary biliary cholangitis

- Secondary biliary cirrhosis

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Autoimmune cholangiopathy, IgG4 cholangiopathy

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Budd–Chiari syndrome

- Intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary obstruction: Recurrent biliary obstruction (e.g., gallstones)

- Inherited metabolic liver disease

- Hemochromatosis

- Wilson’s disease

- α1 antitrypsin deficiency

- Cystic fibrosis

- Glycogen storage disease

- Drug-induced cirrhosis: For example, methotrexate, methyldopa, isoniazid, phenylbutazone, sulfonamides

- Others: Indian childhood cirrhosis, cardiac cirrhosis, chronic venous outflow obstruction, celiac disease Hereditary hemo-telangiectasia, infection [e.g., brucellosis, syphilis, echinococcosis, porphyria, idiopathic adulthood ductopenia (Caroli disease)]

Pathology and Pathogenesis of Cirrhosis:

- Chronic injury to the liver results in inflammation and widespread necrosis of liver cells and, eventually, fibrosis. Fibrosis is due to activation of the stellate cells (in the space of Disse) by many cytokines and their receptors, reactive oxygen intermediates, and other paracrine and autocrine signals. TGF-β is the most potent fibrogenic mediator.

- Cirrhotic changes affect the whole liver, but not necessarily every lobule.

- Extensive fibrosis that distorts and results in loss of liver architecture.

- Regenerating nodules are produced due to hyperplasia of the remaining surviving liver cells.

- Destruction and distortion of hepatic vasculature by fibrosis lead to obstruction of blood flow. Vascular reorganization leads to portal hypertension and its sequelae (gastroesophageal varices and splenomegaly).

- Ascites and hepatic encephalopathydevelop due to hepatocellular insufficiency and portal hypertension.

- Hepatocellular damage produces jaundice, edema, coagulopathy, and a various metabolic abnormalities.

Alcoholic Cirrhosis:

- Safe limits of alcohol are 200 g (20–40 g/day) in males and 140 g (16–30 g/day) in females of alcohol per week. Intake of 180 g of alcohol/day for 25 years increases the risk of cirrhosis by 25 times.

- Development of cirrhosis is six-fold when alcohol consumption is double the safety limit.

- Hepatitis C infection is an important contributory factor for progression to cirrhosis.

- Pathogenesis of alcoholic cirrhosis.

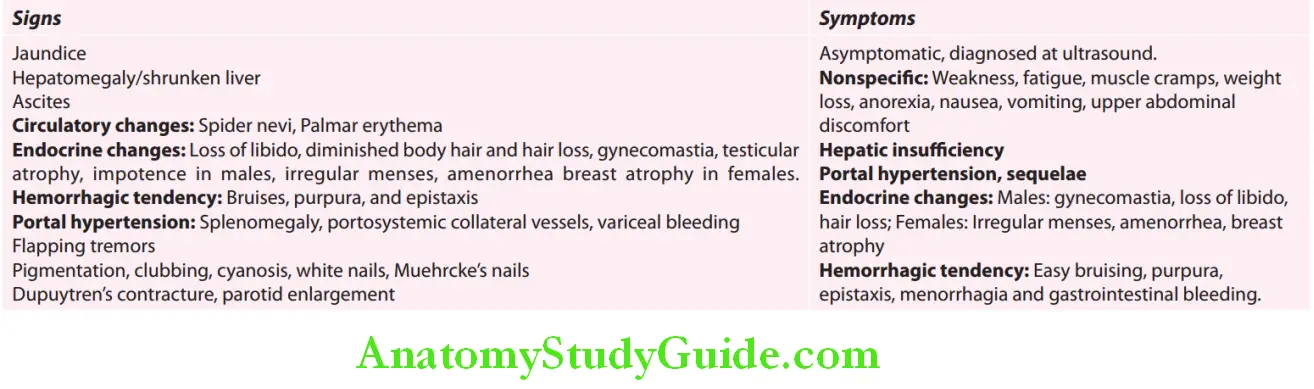

Clinical Features:

Question 36. Write the clinical features and treatment of alcoholic cirrhosis.

Answer:

Alcoholic cirrhosis Symptoms:

- Highly variable and in some patients it may be completely asymptomatic and is incidentally diagnosed at ultrasound or at surgery.

- Nonspecific symptoms: Weakness, fatigue, muscle cramps, weight loss, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and upper abdominal discomfort.

- Symptoms of hepatic insufficiency

- Symptoms of portal hypertension and its sequelae

- Symptoms due to endocrine changes:

- Loss of libido, hair loss

- Females: Irregular menses, amenorrhea, and atrophy of breast

- Males: Gynecomastia, testicular atrophy, and impotence.

- Hemorrhagic tendencies: Due to decreased production of coagulation factors by the liver and thrombocytopenia resulting from hypersplenism. These include easy bruising, purpura, epistaxis, menorrhagia, and GI bleeding.

Alcoholic cirrhosis Signs:

Summary of signs of cirrhosis of liver:

Jaundice:

- Jaundice is not a common feature of cirrhosis; it is more common with acute diseases.

- Mechanisms of jaundice in cirrhosis:

- Failure to excrete bilirubin (mainly)

- Intrahepatic cholestasis (superadded hepatitis/tumor)

- Hemolysis due to hypersplenism (not a major contributor)

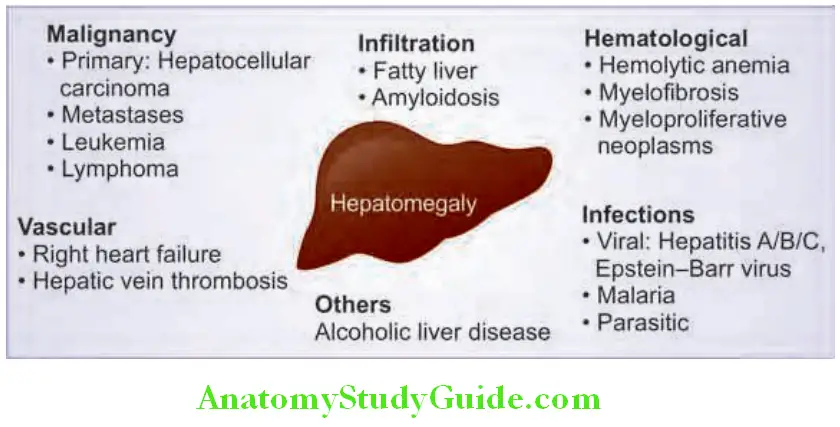

Hepatomegaly:

- Early stages: Liver is enlarged, firm to hard, irregular, and nontender. Hepatomegaly is not common in cirrhosis but common when the cirrhosis is due to alcoholic liver disease, NASH, and hemochromatosis. Hepatomegaly may indicate transformation into HCC.

- Late stages: Liver decreases in size and nonpalpable due to progressive destruction of liver cells and accompanying fibrosis.

Ascites:

Ascites due to liver failure and portal hypertension signify advanced disease.

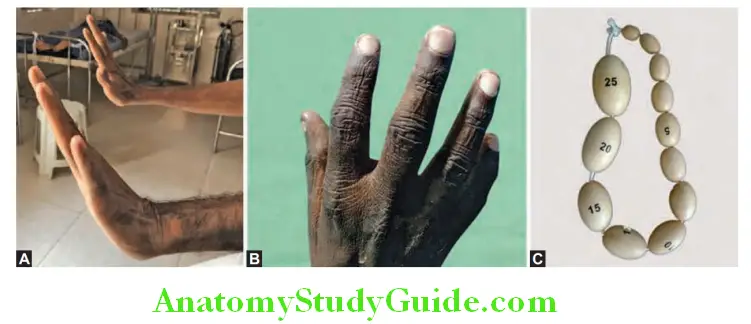

Circulatory changes:

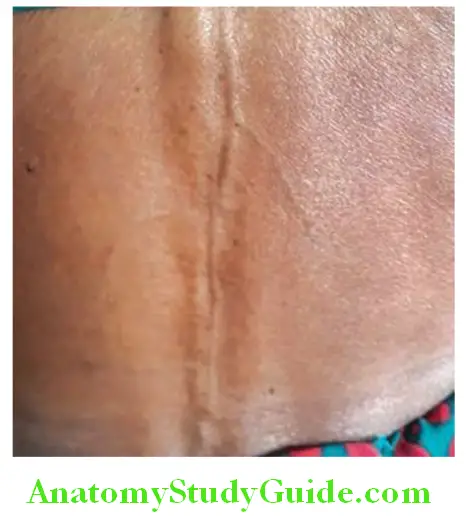

1. Spider nevi (Spider telangiectasia, vascular spiders, spider angiomas, arterial spiders).

- Appearance: Consists of a central arteriole from which numerous small vessels radiate peripherally-resembling spider’s legs. Whole spider disappears when central arteriole is compressed with a pinhead. When compression is released filling occurs from center to periphery.

- Cause: Due to arteriolar changes induced by hyperestrogenism.

- Sites affected: Usually found only in the necklace area, i.e., above the nipples, territory drained by the superior vena cava such as head and neck, upper limbs, front and back of upper chest. Most probable cause of location in the superior vena cava drainage area in that maximum blood in the portal circulation that cannot go through the liver due to fibrosis reach the systemic circulation through the SVC.

- Size: Varies from pinhead to 0.5 mm in diameter.

- Significance: They are a strong indicator of liver disease but can be found in other conditions.

- Florid spider telangiectasia, gynecomastia, and parotid enlargement are most common in alcoholic hepatitis.

- Florid spiders and new-onset clubbing in a patient with cirrhosis indicate hepatopulmonary syndrome.

- Differential diagnosis for spider nevi includes venous star, Campbell de Morgan spots, petechiae, and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias.

2. Palmar erythema (liver palm):

- Can be seen early but is of limited diagnostic value, as it occur in many conditions associated with a hyperdynamic circulation (e.g., normal pregnancy).

- Cause: Develops due to increased peripheral blood flow. In cirrhosis, circulatory changes results in increased peripheral blood flow and decreased visceral blood flow (especially to the kidneys).

- Sites involved: Prominent in the thenar and hypothenar eminences of palm. May be seen on the sole.

Conditions associated with spider nevi:

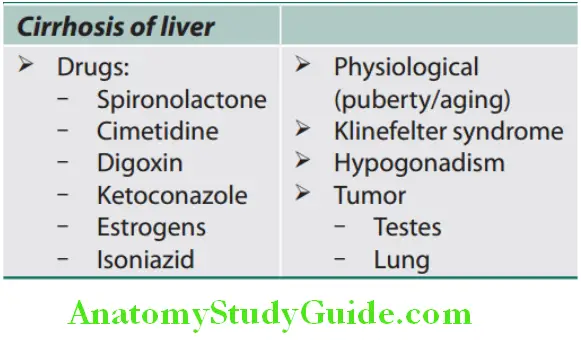

Endocrine changes:

- Diminished body hair and loss of hair:

- Seen mainly in males with loss of male hair distribution

- Alopecia affects usually the face, axilla, and chest and is due to hyperestrogenism