Infections

Granulomatous Diseases

Mycobacterium is a bacteria, that appears as slender aerobic rods that grow in straight or branching chains. Mycobacteria have a waxy cell wall composed of mycolic acid, which is responsible for their acid-fast nature. Mycobacteria are weakly Gram-positive.∼

Table of Contents

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (also called Koch’s disease) is a communicable, chronic granulomatous disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- Most cases of tuberculosis are caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis hominins (human strain). The source of infection is patients with active open case of tuberculosis.

- Oropharyngeal and intestinal tuberculosis can be caused by drinking milk contaminated with M. bovis (bovine strain) from infected cows. Routine pasteurization has almost eliminated this source of infection.

- M. avium and intracellular, which are nonpathogenic to normal individuals but cause infection in patients with AIDS.

Read And Learn More: Pathology for Dental Students Notes

Characteristics of Mycobacteria:

- It is an aerobic, slender, rod-shaped bacteria measuring 2 to 10 µm in length.

- It has a lipid coat which makes it difficult to stain, but once stained resists decolorization by acids and alcohol. Hence, it is termed as acid-fast bacilli (AFB), because once stained by carbol fuchsin (present in Ziehl-Neelsen stain), it is not decolorized by acid and alcohol.

Epidemiology of Mycobacteria:

- Tuberculosis is common in India. The incidence of tuberculosis is high wherever there is poverty, overcrowding, and chronic debilitating illness.

- Diseases are associated with increased risk: diabetes mellitus, Hodgkin lymphoma, malnutrition, immunosuppression, alcoholism, chronic lung disease (for example, Silicosis), and chronic renal failure.

- HIV is the most important risk factor.

Read And Learn More: Pathology for Dental Students Notes

Infection Versus Disease:

Infection with M. tuberculosis is to be differentiated from the disease.

- Infection: Tuberculous infection indicates the presence of organisms in a person, which may or may not cause symptomatic disease.

- Disease: Active tuberculosis refers to a subset of tuberculous infections manifested by destructive, symptomatic disease.

Mode of Transmission:

- Inhalation: It is the most common mode of transmission.

- The source of organisms is from an active open case of tuberculosis to a susceptible host.

- Tubercle bacilli will be expelled while coughing, and sneezing which creates aerosolized respiratory droplets.

- When an individual inhales the droplets, it lodge in the lung and cause infection.

- Ingestion: Tuberculosis may be transmitted by drinking nonpasteurized milk from infected cows contaminated with M. bovis.

- Site of infection: Mycobacterium bovis causes oropharyngeal and intestinal tuberculosis.

- Eradication of tuberculous herds with tuberculosis and pasteurization has almost eliminated this mode of transmission of tuberculosis.

- Nowadays the ingestion mode of transmission occurs when a patient with an open case of tuberculosis swallows the infected sputum resulting in tuberculosis of intestine.

- Inoculation: It is an extremely rare mode of transmission. May develop during postmortem examination, while cuts resulting from handling tuberculous infected organs.

Tuberculin (Mantoux) Test:

- Infection by mycobacteria → development of delayed hypersensitivity to M. tuberculosis antigens → which is detected by the tuberculin skin test.

- About 2 to 4 weeks after infection, intracutaneous injection of 0.1 mL of purified protein derivative (PPD) of M. tuberculosis produces a visible and palpable induration of 10 mm diameter or more at the site of injection of PPD. The induration peaks in 48 to 72 hours.

Signifiance of TuberculinTest:

- Positive tuberculin test: It indicates T cell-mediated immunity to mycobacterial antigens.

- False-negative reactions: It is seen in certain viral infections, sarcoidosis, malnutrition, Hodgkin lymphoma, immunosuppression, and overwhelming active tuberculous disease

- False-positive reactions: It is seen in infection by atypical mycobacteria or prior vaccination with BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guerin).

Pathogenesis of TuberculinTest:

Pathogenesis of tuberculosis.

Immunity and hypersensitivity: Infection with tubercle bacillus results in two simultaneous immunological responses.

- Cell-mediated immunity

- Type 4 hypersensitivity reaction.

The effector cells for both cell-mediated immunity and hypersensitivity reaction are TH1 cells:

- Cell-mediated immunity: Tuberculosis developing first time in an immunocompetent individual depends on cell-mediated immunity.

- Type 4 hypersensitivity reactions: Develops to mycobacterial antigens and is responsible for tissue destruction such as caseating granulomas and cavitation. The appearance of type 4 hypersensitivity reaction also signals the development of protective immunity.

Mechanism of Granuloma Formation in Tuberculosis:

Tuberculosis is a chronic granulomatous disease, caused by M. tuberculosis. Lung being commonly involved in tuberculosis, the pathogenesis is considered with respect to pulmonary tuberculosis.

1. First 0–3 weeks after exposure: Initial infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a nonsensitized individual is called primary tuberculosis. The following sequence of events occurs:

- Phagocytosis of mycobacteria by macrophages: First time, when the virulent tubercle bacilli are deposited in the tissue, they primarily infect macrophages. In the lung, they undergo endocytosis into the alveolar macrophages through macrophage receptors

- These receptors include:

- Mannose receptors bind lipoarabinomannan (LAM), a glycolipid in the cell wall of tubercle bacilli

- Complement receptors (C3b receptor) bind mycobacteria opsonized by C3b.

- The proliferation of mycobacteria within macrophages:

- First 3 weeks: Tubercle bacilli proliferate freely within the phagosome of the macrophage by blocking the fusion of the phagosome and lysosome. It may result in bacteremia and seeding of tubercle bacilli at many sites.

- Genetic factor: NRAMP1 is a transmembrane protein (a product of the NRAMP1 gene) that inhibits microbial growth.

2. After 3 weeks of infection:

- Cell-mediated immunity: It develops about 3 weeks after exposure.

- Presentation of antigen to CD4+ T cells: Antigen-presenting cells (APCs which include macrophages, and dendritic cells) process the mycobacterial antigen and present it to naïve CD4+ T cells. Processed antigen reaches regional lymph nodes.

- Differentiation of CD4+ T cells into T-helper 1 (TH1) cells: This is due to the action of IL-12 secreted by macrophages.

Role of TH1 cells:

- T H1 cells produce IFN-γ which has several functions.

- Activation of macrophages: The macrophages become bactericidal and secrete TNF → which promotes the recruitment of more monocytes → differentiation into epithelioid (epithelium-like) cells.

- Stimulates formation of the phagolysosome in infected macrophages → exposes the bacteria to an acidic environment.

- Stimulates nitric oxide synthase → to produce nitric oxide → antibacterial.

- Generation of reactive oxygen species → antibacterial.

- TH1 is also responsible for the formation of granulomas and caseous necrosis.

- Transformation of macrophages into epithelioid cells: Activated macrophages are transformed into epithelioid cells. Some of these “epithelioid cells” may fuse to form giant cells.

- Granuloma formation: A microscopic aggregate of epithelioid cells, surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, is referred as a granuloma and this pattern of inflammation, is known as granulomatous inflammation.

- Hypersensitivity reaction results in tissue destruction → caseation and cavitation.

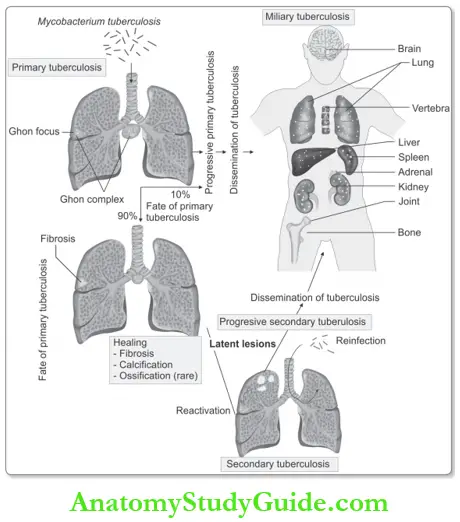

Primary Tuberculosis

Write a short note on primary tuberculosis.

- Initial infection that occurs on first exposure to the organism in an unsensitized (previously unexposed) individual is known as primary tuberculosis.

- About 5% of newly infected people develop clinically significant diseases.

- The source of the organism is always exogenous.

Morphology primary tuberculosis:

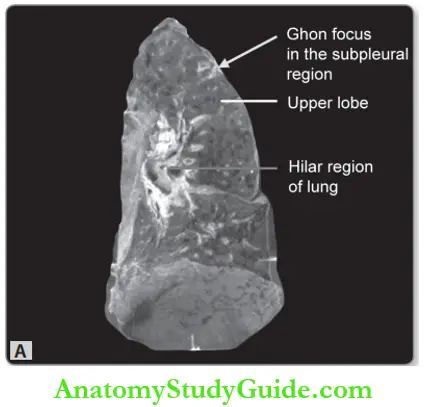

Write a short note on Ghon’s focus.

Or

Write a short note on the Ghon complex.

Sites of Primary Tuberculosis: Lung, intestine, tonsil, and skin (very rare).

Lung: It is the commonest site of primary tuberculosis.

- Ghon lesion: Following inhalation, tubercle bacilli get deposited in the distal airspaces.

- Site of deposit: Usually lower part of the upper lobe or upper part of the lower lobe near the pleural surface (subpleural).

- Ghon focus: About 2 to 4 weeks after the infection, a circumscribed gray-white area of about 1- to 1.5 cm develops in the lung known as the Ghon focus→ the center of which undergoes caseous necrosis.

- Regional lymphadenitis: Tubercle bacilli (free or within macrophages) are carried along the lymphatics to the regional draining nodes → which often show caseous necrosis.

- Ghon complex: It is the combination of subpleural parenchymal lung lesion (Ghon focus) and regional lymph node involvement.

- The fate of the Ghon complex:

- Healing: In the majority (about 95%), cell-mediated immunity controls the infection and primary tuberculosis heals. The hallmark of healing is fibrosis and Ghon complex undergoes progressive fibrosis, followed by radiologically detectable calcification (Ranke complex), and very rarely ossification.

- Spread: During the first few weeks lymphatic and hematogenous dissemination occurs to other organs or parts of the body.

Other Sites of Primary Complex:

- Intestine: Primary focus in the small intestine (usually ileal region) along with mesenteric lymphadenitis.

- Tonsils: Primary focus in the pharynx and tonsil with cervical lymph node enlargement.

- Skin: Primary focus on the skin along with regional lymph node involvement.

Microscopy of Primary Tuberculosis:

Granuloma in tuberculosis is called a tubercle:

Tubercle may show the central area of caseous necrosis (caseating granuloma) or may not show caseation (noncaseating tubercles). Individual tubercles are identified only by microscopic examination. When multiple granulomas coalesce → they may be grossly identified.

Caseating granuloma consists of:

- The central area of caseous necrosis

- Surrounded by epithelioid cells (modified macrophages), some of which may fuse to form multinucleate giant cells. The giant cells may be Langhans type (nuclei arranged in a horseshoe pattern) or foreign body type (nuclei in the center).

- The epithelioid cells are surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes.

- These granulomas are usually enclosed within fibroblasts.

Secondary Tuberculosis

Secondary Tuberculosis (Synonyms: Post-primary tuberculosis, reactivation tuberculosis)

- Tuberculosis developing in a previously sensitized individual is known as secondary tuberculosis.

- It may follow shortly or many years after primary tuberculosis, usually when the resistance host decreases.

- Source of infection:

- The most common source is the reactivation of a latent infection

- Rarely exogenous reinfection.

- Any location may be involved in secondary tuberculosis, but the lungs are by far the most common site.

Morphology of Secondary Tuberculosis:

- Gross:

- Site: In the lungs, secondary tuberculosis usually involves the apex of the upper lobes of one or both lungs, within 1 to 2 cm of the apical pleura.

- Appearance: Initially- small focus (less than 2 cm in diameter) of consolidation, sharply circumscribed, firm, and gray-white to yellow in color.

- Regional lymph node involvement is less prominent than in primary tuberculosis.

Microscopy of Secondary Tuberculosis:

- Active lesions show caseating granulomas and acid-fast stain often shows tubercle bacilli.

- Natural history and various stages of tuberculosis are depicted below.

Fate of Secondary Tuberculosis:

- Healing: In immunocompetent individuals, localized, apical, focus may heal with fibrosis and calcification rarely ossification.

- Progress: It may occur along several different pathways.

Progressive pulmonary tuberculosis:

It occurs mainly in the elderly and immunosuppressed. The apical lesion may expand into the surrounding lung and may erode into bronchi and vessels.

- Erosion into bronchi: It leads to the release of the central area of caseous necrosis→ resulting in a ragged, irregular apical cavity surrounded by fibrous tissue.

- This produces an important source of infection, because when the patient coughs, sputum contains bacteria.

- Erosion of blood vessels: may result in hemoptysis.

With prompt treatment, it may undergo healing by fibrosis.

Spread of infection:

If the treatment is inadequate or if host defenses are impaired, the infection may spread via:

- Airways

- Lymphatics

- Blood vessels.

1. Local/direct spread: Tuberculosis can directly spread to the surrounding tissue. In the lung local spread to the pleura and shift up as first bullet. Resulting in serous pleural effusion, tuberculous empyema, or obliterative fibrous pleuritis.

2. Spread through bronchi/airways: It may produce tuberculous pneumonia.

- Intestinal tuberculosis: In the past, intestinal tuberculosis resulted from the drinking of contaminated milk, and with pasteurization of milk, now it is rare. Nowadays caused by the swallowing of coughed-up infective material in patients with open cases of advanced pulmonary tuberculosis. Mainly develops in the ileum

3. Spread along mucosal lining: Spread through lymphatic channels or along the mucosal lining from mycobacteria present in the expectorated infectious material may lead to endobronchial, endotracheal, and laryngeal tuberculosis.

4. Lymphatic spread: Spread through lymphatic channels mainly reaches regional lymph nodes. It may also cause disseminated disease.

- Miliary pulmonary disease: It is the disseminated form of tuberculosis. When the dissemination occurs only to the lungs, it is called miliary pulmonary disease.

- Mechanism of development: Tubercle bacilli draining through lymphatics → enter the venous blood → to the right venous side of the heart → through pulmonary artery → to the lung.

- Lesions: Multiple, small, yellow, nodular lesions in the lung parenchyma of both lungs. Each lesson is either microscopic or small, and visible (2-mm) foci of yellow-white consolidation → resemble millet seeds, hence named “military”.

- Lymphadenitis: It is the most frequent presentation of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, and usually occurs in the cervical region (“scrofula”).

- HIV-negative individuals: Unifocal and localized.

- HIV-positive individuals: Multifocal and systemic disease.

5. Spread via blood vessels:

- Systemic miliary tuberculosis occurs when tubercle bacilli disseminate through the systemic arterial system. Miliary tuberculosis most commonly involves the liver, bone marrow, spleen, adrenals, meninges, kidneys, fallopian tubes, and epididymis. But no organ is exempt and can involve any organ.

- Isolated-organ tuberculosis: Dissemination of tubercle bacilli through blood may seed any organ or tissue → resulting in isolated organ tuberculosis.

- Commonly involved organs are:

- Meninges (tuberculous meningitis)

- Kidneys (renal tuberculosis)

- Adrenals

- Bones (osteomyelitis): When it involves the vertebrae, the disease is referred to as Pott disease. Paraspinal “cold” abscesses may track along tissue planes and present as an abdominal or pelvic mass. Fallopian tubes (salpingitis).

Clinical Features of Secondary Tuberculosis:

- Localized secondary tuberculosis may remain asymptomatic.

- Systemic symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis:

- Nonspecific: malaise, anorexia, weight loss, and fever.

- Low-grade fever: It is remittent (appearing late each afternoon and then subsiding-commonly known as evening rise of temperature), and night sweats.

- Sputum: It is first mucoid and later purulent.

- Hemoptysis: It is present in 50% of cases of pulmonary tuberculosis.

- Pleuritic pain: It is due to an infection of the pleural surfaces.

- Extrapulmonary manifestations depend on the organ/system involved.

The main differences between primary and secondary tuberculosis of the lung are listed in the table.

The main difference between primary and secondary tuberculosis of the lung:

Diagnosis And Pulmonary Disease

Write a short note on the diagnosis of tuberculosis.

- Based on the history, physical and radiographic findings.

- Identifiation of acid-fast tubercle bacilli in the sputum.

- Culture of the sputum: Conventional cultures require up to 10 weeks. Culture is the gold standard.

- PCR amplification of M: Tuberculosis: DNA is the rapid method of diagnosis. PCR can detect as few as 10 organisms in clinical specimens.

- Prognosis: Generally good if infections are localized to the lungs. All stages of HIV infection are associated with an increased risk of tuberculosis.

Leprosy

Leprosy (Hansen disease), is a chronic, granulomatous, slowly progressive, destructive infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae.

Sites of involvement:

- Mainly involves the peripheral nerves, skin, and mucous membranes (nasal) and results in disabling deformities.

- Leprosy is one of the oldest human diseases and lepers were isolated from the community in the olden days.

Mycobacterium leprae or Leprosy:

- Slender, weakly acid-fast intracellular bacillus.

- Proliferates at low temperatures of the human skin.

- Cannot be cultured on artificial media or in cell culture.

Experimental animals: Lepra bacilli grow at sites where the temperature is below that of the internal organs.

- Examples: Footpads of mice, ear lobes of hamsters, rats, and other rodents.

- Experimentally transmitted to nine branded armadillos (they have low body temperatures ranging from 32° to 34°C).

Mode of transmission: It has comparatively low communicability.

1. Inoculation/inhalation:

Likely to be transmitted from person to person through aerosols from asymptomatic lesions in the upper respiratory tract. Inhaled M. leprae, is taken up by alveolar macrophages and disseminates through the blood, but replicates only in relatively cool tissues of the skin and extremities.

2. Intimate contact: For many years.

- Source of infection: M. leprae is present in nasal secretions or ulcerated lesions of patients suffering from leprosy.

- Incubation period: Generally 5 to 7 years.

Classification Mycobacterium leprae or Leprosy:

Classify leprosy.

1. Ridley-Jopling’s (1966) classification: It depends on the clinicopathological spectrum of the disease, which is determined by the immune resistance of the host. They are classified into fie groups with two extreme or polar forms, namely tuberculoid and lepromatous types.

- Tuberculoid leprosy (TT): It is the polar form that has a maximal immune response.

- Borderline tuberculoid (BT): In this type, the immune response falls between BB and TT.

- Borderline leprosy (BB): It exactly falls between two polar forms of leprosy.

- Borderline lepromatous (BL): It has an immune response that falls between BB and LL.

- Lepromatous leprosy (LL): It is the other polar form with the least immune response.

2. WHO classification:

- Paucibacillary: All cases of tuberculoid leprosy and some cases of borderline type.

- Multibacillary: All cases of lepromatous leprosy and some cases of borderline type.

Pathogenesis Mycobacterium leprae or Leprosy:

- M. leprae does not secrete any toxins, and its virulence depends on the properties of its cell wall (similar to that of M. tuberculosis), and immunization with BCG may provide some protection against M. leprae infection.

- Cell-mediated immunity is reflected by delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions to dermal injections of a bacterial extract called lepromin.

- The T-helper (TH1) lymphocyte response to M. leprae, determines whether an individual develops a tuberculoid or lepromatous type of leprosy.

- Tuberculoid: Tuberculoid leprosy patients have a TH1 response which secretes IL-2 and IFN-γ. The latter (IFN-γ) is essential for an effective host macrophage response.

- Lepromatous: Lepromatous leprosy patients have a weak TH1 response and, in some a relative increase in the TH2 response → results in a poor cell-mediated immunity → proliferation of lepra bacilli.

Morphology Mycobacterium leprae or Leprosy:

Write a short note on the morphology of tuberculoid leprosy.

Or

Write a short note on the morphology of lepromatous leprosy.

Two extremes or polar forms of the diseases are the tuberculoid and lepromatous types.

1. Tuberculoid leprosy: It is the less severe form of leprosy. It is very slow in its course and most patients die with leprosy.

- The lesion in the skin:

- Number of lesions: Single or very few lesions.

- Site: Usually on the face, extremities, or trunk

- Type: Localized, well-demarcated, red or hypopigmented, dry, elevated, skin patches having raised outer edges and depressed pale centers (central healing). As they progress they develop irregular shapes with induration.

- Nerve involvement:

- Dominating feature in tuberculoid leprosy.

- Nerves are surrounded by granulomatous inflammatory reactions and, may destroy small (for example, Peripheral twigs) nerves.

- Nerve involvement → causes loss of sensation in the skin → atrophy of skin and muscle. These affected parts are liable to trauma and lead to the development of chronic skin ulcers.

- Consequences: It may lead to contractures, paralyzes, and autoamputation of fingers or toes. Involvement of facial nerve can lead to paralysis of the eyelids, with keratitis and corneal ulcerations.

Microscopy Mycobacterium leprae or Leprosy:

- Granuloma: These are well-formed, circumscribed, and non-caseating (no caseation). Seen in all involved sites and in the dermis of the skin. Termed tuberculoid leprosy because the granulomas resemble those found in tuberculosis. Granulomas are composed of epithelioid cells (modified macrophages), Langhans giant cells, and lymphocytes.

- Absence of Grenz zone: Granulomas in the dermis extend to the basal layer of the epidermis (without a clear/Grenz zone).

- Fite-Faraco (modified Z-N stain for demonstration of lepra bacillus): The stain generally does not show lepra bacillus, hence the name “paucibacillary” leprosy.

- Perineural (surrounding nerve fibers) inflammation: By lymphocytes.

- Strong T-cell immunity: It is responsible for granuloma formation, without lepra bacilli.

2. Lepromatous leprosy: It is the more severe form and is also called anergic leprosy, because of the unresponsiveness (anergy) of the host immune system.

Sites involved:

- Lesion in skin:

- Thickening of skin and multiple, symmetric, macular, papular, or nodular lesions. The nodular skin lesions may ulcerate. Most skin lesions are hyperesthetic or anesthetic.

- More severe involvement of the cooler areas of skin (for example, Earlobes, Wrists, Elbows, Knees, And Feet), than warmer areas (for example, Axilla and groin).

- With progression, the nodular lesions in the face and ear lobes may coalesce to produce a lion-like appearance known as leonine facies. This may be accompanied by loss of eyebrows and eyelashes.

- Peripheral nerves:

- Particularly the ulnar and peroneal nerves are symmetrically invaded with mycobacteria.

- Loss of sensation and trophic changes in the hands and feet may follow the damage to the nerves.

- Testes: Usually severely involved, leading to the destruction of the seminiferous tubules → sterility.

- Other sites:

- Anterior chamber of the eye: Blindness.

- Upper airways: Chronic nasal discharge and voice change

Microscopy of skin lesion :

- Flattened epidermis: Epidermis is thinned and flattened (loss of rete ridges) over the nodules.

- Grenz (clear) zone: It is a characteristic narrow, uninvolved dermis (normal collagen) that separates the epidermis from nodular accumulations of macrophages.

- Lepra cells: The nodular lesions contain large aggregates of lipid-laden foamy macrophages (lepra cells, Virchow cells), filled with aggregates (“globe”) of acid-fast lepra bacilli (M. leprae).

- Fite-Faraco (acid-fast) stain: It shows numerous lepra bacilli (“red snappers”) within the foamy macrophages.

- They may be arranged in a parallel fashion like cigarettes in a pack.

- Due to the presence of numerous bacteria, lepromatous leprosy is also referred to as “multibacillary”.

In advanced cases, M. leprae may be present in sputum and blood. Individuals with intermediate forms of the disease, called borderline leprosy

Lepromin Test:

Write a short note on the lepromin test.

It is not a diagnostic test for leprosy. It is used for classifying leprosy based on the immune response.

- Procedure: An antigen extract of M. leprae called lepromin is intradermally injected.

- Reaction:

- An early positive reaction appears as an indurated area in 24 to 48 hours is called

- Fernandez reaction.

- A delayed granulomatous reaction appearing after 3 to 4 weeks is known as the Mitsuda reaction.

- Interpretation:

- Lepromatous leprosy — shows a negative lepromin test due to suppression of cell-mediated immunity.

- Tuberculoid leprosy — shows positive lepromin test because of delayed hypersensitivity reaction.

Differences between lepromatous and tuberculoid leprosy are presented in Table.

Diagnosis of Leprosy:

List the differences between lepromatous and tuberculoid leprosy.

1. Clinical examination:

- Sensory testing

- Examination of peripheral nerve

Differences between lepromatous and tuberculoid leprosy:

2. Demonstration of acid-fast bacilli:

- Skin smears prepared by slit and scrape method

- Nasal swabs stained by the Ziehl-Neelsen method

3. Skin biopsy

4. Nerve biopsy

5. Molecular method: PCR.

Syphilis

Introduction of Syphilis:

- Spirochetes are gram-negative, slender corkscrew-shaped bacteria covered in a membrane called an outer sheath, which may mask its antigens from the host immune response.

- Syphilis (lues) is a chronic, sexually transmitted disease caused by spirochete Treponema pallidum.

Etiology of Syphilis:

1. Treponema pallidum:

- It is a thin, delicate, corkscrew-shaped spirochete, measures about 10 µm long with tapering ends, and has about 10 regular spirals.

- Actively motile, showing rotation around the long axis, backward and forward motion.

- Cannot be grown in artificial media.

Staining: It does not stain with ordinary bacterial stains and is too slender to be seen in Gram stain. It can be visualized by silver stains, dark-field examination, and immunofluorescence techniques.

- Source of infection: An open lesion of primary or secondary syphilis. Lesions in the mucous membranes or skin of the genital organs, rectum, mouth, fingers, or nipples.

- Mode of transmission:

- Sexual contact: It is the usual mode of spread.

- Transplacental transmission: From mother with active disease to the fetus (during pregnancy) → congenital syphilis.

- Blood transfusion

- Direct contact: With open lesion is a rare mode of transmission.

Basic Microscopic Lesion:

Irrespective of the stage, the basic microscopic lesion of syphilis consists of

- Mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate: Predominantly of plasma cells and lymphocytes.

- Obliterative endarteritis: It is a characteristic obstructive vascular lesion in which mononuclear infiltrates surround small arteries and arterioles (periarteritis).

Stages of Syphilis:

T. pallidum passes from the site of inoculation to regional lymph nodes enters to the systemic circulation, and disseminates throughout the body. Syphilis can be

- Congenital or

- Acquired.

The course of acquired syphilis is divided into three stages:

- Primary syphilis

- Secondary syphilis

- Tertiary syphilis.

Primary Syphilis:

Develops about 3 weeks after contact with an infected individual and the lesion is the primary chancre.

Primary Chancre:

Write a short note on the chancre.

It is the classical lesion of primary syphilis.

Sites: Penis or scrotum in men and cervix, vulva, and vaginal wall in women. It may also be seen in the anus or mouth.

Gross features: It is single, firm, non-tender (painless), slightly raised, red papule (chancre) up to several centimeters in diameter. It erodes to create a clean-based shallow ulcer. Because of the induration surrounding the ulcer, it is designated as a hard chancre.

Demonstration of treponema: Plenty of treponemes can be demonstrated in the chancre by

- Silver stains (for example, Warthin-Starry stain) or

- Immunofluorescence techniques or

- Darkfield examination.

Microscopy of Primary Chancre:

- Mononuclear infiltration: Consisting of plasma cells, with scattered macrophages and lymphocytes. These cells are also seen surrounding the blood vessels (periarteritis).

- Blood vessels with endarteritis: It is characterized by endothelial cell proliferation which progresses to intimal fibrosis.

Regional Lymphadenitis:

- It is due to nonspecific acute or chronic inflammation.

- Treponemes may spread throughout the body by blood and lymphatics even before the appearance of the chancre.

- Symptoms: Usually painless and often unnoticed.

- Fate: It heals in 3 to 6 weeks with or without therapy.

Secondary Syphilis:

Write a short note on oral lesions of syphilis.

- It develops 2 to 10 weeks after the primary chancre in approximately 75% of untreated patients.

- Its manifestations are due to systemic spread and proliferation of the spirochetes within the skin and mucocutaneous tissues.

Lesions of Secondary Syphilis:

- Mucocutaneous Lesions

- These are painless, superficial lesions that contain spirochetes and are infectious.

Skin lesions:

- Skin rashes: Consist of discrete red-brown macules less than 5 mm in diameter, but they may be scaly/pustular/annular. They are more frequent on the palms of the hands or soles of the feet.

- Condylomata lata: These are broad-based, elevated plaques with numerous spirochetes. They are seen in moist areas of the skin, such as the anogenital region (perineum, vulva, and scrotum), inner thighs, and axillae.

- Mucosal lesions: Usually occurs in the mucous membranes of the oral cavity or vagina as silvery-gray superficial erosions. These lesions contain numerous T. pallidum and are highly infectious.

- Microscopy of Secondary Syphilis: Similar to primary chancre, i.e. infiltration by plasma cells and endarteritis obliterans.

- Painless Lymphadenopathy: This especially involves epitrochlear nodes and shows plenty of spirochetes.

- Symptoms: Mild fever, malaise, and weight loss are common in secondary syphilis, which may last for several weeks. The lesions subside even without treatment.

Tertiary Syphilis:

- After the lesions of secondary syphilis have subsided patients enter an asymptomatic latent phase of the disease.

- The latent period may last for 5 years or more (even decades), but spirochetes continue to multiply.

- This stage is rare if the patient gets adequate treatment, but can occur in about one-third of untreated patients.

- Focal ischemic necrosis due to obliterative endarteritis is responsible for many of the processes associated with tertiary syphilis.

Manifestations: Three main manifestations of tertiary syphilis are: cardiovascular syphilis, neurosyphilis, and so-called benign tertiary syphilis. These may occur alone or in combination.

Cardiovascular Syphilis:

Most frequently involves the aorta and is known as syphilitic aortitis.

- Syphilitic aortitis: Accounts for more than 80% of cases of tertiary disease, and affects the proximal aorta.

- Saccular aneurysm and aortic valve insufficiency:

- Occlusion of the vasa vasorum due to endarteritis leads to necrosis and scarring of the aortic media, causing a loss of elasticity, strength and resilience.

- Gradual weakening and slow progressive dilation of the aortic root and arch causes, aortic valve insufficiency and aneurysms of the proximal aorta.

- Syphilitic aneurysms are saccular and seen in the ascending aorta, which is an unusual site for the more common atherosclerotic aneurysms.

- On gross examination, the aortic intima appears rough and pitted (tree-bark appearance).

- Myocardial ischemia: Narrowing of the coronary artery ostia (at the origin of the aorta) caused by subintimal scarring may lead to myocardial ischemia/infarction.

Neurosyphilis:

It may be asymptomatic or symptomatic.

1. Asymptomatic neurosyphilis: It is detected by CSF examination, which shows pleocytosis (increased numbers of inflammatory cells), elevated protein levels, or decreased glucose. Antibodies can also be detected in the CSF, which is the most specific test for neurosyphilis.

2. Symptomatic disease: Takes one of several forms

- Chronic meningovascular disease: Chronic meningitis → involves the base of the brain, cerebral convexities, and spinal leptomeninges.

- Tabes dorsalis: It is characterized by demyelination of the posterior column, dorsal root, and dorsal root ganglia.

- General paresis of insane: Shows generalized brain parenchymal disease with dementia; hence called general paresis of insane.

Benign Tertiary Syphilis:

Write a short note on Gumma.

- It is characterized by the formation of nodular lesions called gummas in any organ or tissue.

- Gammas reflect the development of delayed hypersensitivity to the spirochete. Gummas are very rare and may be found in patients with AIDS.

Syphilitic gummas:

- May be single or multiple.

- White-gray and rubbery.

- Vary in size from microscopic lesions to large tumor-like masses.

- Site: They occur in most organs but mainly involve

- Skin, subcutaneous tissue, and the mucous membranes of the upper airway and mouth.

- Bone and joints: It causes local pain, tenderness, swelling, and sometimes pathologic fractures.

- In the liver, scarring due to gummas may cause a distinctive hepatic lesion known as hepar located.

Microscopy of Tertiary Syphilis:

The center of the gammas shows coagulative necrosis → surrounded by plump, palisading macrophages, fibroblasts, and plenty of plasma cells. Treponemes are scant in gummas.

Congenital Syphilis:

Write a short note on congenital syphilis Or Oral lesions of congenital syphilis. Features of congenital syphilis.

Transplacental Transmission:

- T. pallidum can cross the placenta and spread from the infected mother to the fetus (during pregnancy).

- Transmission occurs, when the mother is suffering from primary or secondary syphilis (when the spirochetes are abundant. Because of routine serologic testing for syphilis in done in all pregnancies) congenital syphilis is rare.

Manifestations: Can be divided into

1. Intrauterine death and perinatal death.

2. Early (infantile) syphilis: It occurs in the first 2 years of life and is often manifested by nasal discharge and congestion (snuffle).

- A desquamating or bullous eruption/rash can lead to epidermal sloughing of the skin, mainly in the hands, feet, around the mouth, and anus.

- Skeletal abnormalities:

- Syphilitic osteochondritis: Inflammation of bone and cartilage is more distinctive in the nose. Destruction of the vomer causes the collapse of the nasal bridge → produces characteristic saddle nose deformity.

- Syphilitic periostitis: It involves the tibia and causes excessive new bone formation on the anterior surfaces and leads to anterior bowing or saber shin.

- Liver: Diffuse fibrosis in the liver.

- Lungs: Diffuse interstitial fibrosis → lungs appear pale and airless (pneumonia alba).

Late (tardive) syphilis: Manifests 2 years after birth, and about 50% of untreated children with neonatal syphilis will develop late manifestations.

Manifestations: Distinctive manifestation in Hutchinson’s triad is

- Interstitial keratitis.

- Hutchinson’s teeth: They are like small screwdrivers or peg-shaped incisors, with notches in the enamel.

- Eighth-nerve deafness.

Laboratory Diagnosis:

- Immunofluorescence of exudate from the chancre is important for the diagnosis in primary syphilis.

- Microscopy and PCR are also useful.

Serological tests:

- Nontreponemal antibody tests: These tests measure antibodies to cardiolipin, a phospholipid present in both host tissues and T. pallidum.

- These antibodies are detected by the rapid plasma reagin and Venereal Disease

- Research Laboratory (VDRL) tests.

- False-positive VDRL test: Found in certain acute infections, collagen vascular diseases (for example, Systemic lupus erythematosus), drug addiction, pregnancy, hypergammaglobulinemia of any cause, and lepromatous leprosy.

- Antitreponemal antibody tests: These measure antibodies, which react with T. pallidum. These include

- Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA)

- Microhemagglutination assay for T. pallidum antibodies.

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction:

- Treatment of syphilitic patients having a high bacterial load, by antibiotics can cause a massive release of endotoxins, and cytokine that may manifest with high fever, rigors, hypotension, and leukopenia.

- This syndrome is called the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, which can develop not only in syphilis but also in other spirochetal diseases, such as Lyme disease.

Typhoid Fever

- Typhoid fever (enteric) is an acute systemic disease caused by infection with Salmonella typhi.

- Paratyphoid fever is a clinically similar but milder disease caused by Salmonella paratyphi.

- Enteric fever is the general term, which includes both typhoid and paratyphoid fever.

Etiology of Typhoid fever:

Causative agent:

- Enteric fevers are caused by Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi.

- Salmonella are gram-negative, motile bacilli (rods). Boiling or chlorination of water and pasteurization of milk destroys the bacilli.

Source of infection: Humans are the only natural reservoir and include:

- Patient suffering from disease: Infected urine, feces, or other secretions from patients.

- Chronic carriers of typhoid fever: S. typhi or S. paratyphi colonizes in the gallbladder or biliary tree → may be associated with gallstones and the chronic carrier state.

Mode of transmission: From person-to-person contact.

- Ingestion of contaminated food (especially dairy products) and shellfish or contaminated water.

- Direct spread: Rare by finger-to-mouth contact with feces, urine, or other secretions is rare.

- Incubation period: Usually 7 to 14 days.

Pathogenesis Typhoid fever:

Write a short note on the pathogenesis of typhoid fever.

The typhoid bacilli (Salmonella) are ingested through contaminated food or water → able to survive in gastric acid of the stomach → reach mucosa of small intestine.

- Events during the incubation period:

- During the initial asymptomatic period (about 2 weeks), the Salmonella attach to the microvilli and penetrate the ileal mucosa of the small intestine → reaching lamina propria and submucosa.

- Salmonella is phagocytosed by the macrophages (mononuclear phagocytes) present in the lymphoid tissue and Peyer’s patches in the submucosa of the small intestine.

- Salmonella multiply within the macrophages and are carried to the mesenteric lymph node via lymphatics.

- They multiply in the lymph nodes and via the thoracic duct enter the bloodstream causing transient bacteremia.

- During bacteremia, the bacilli are seeded in many organs.

- They colonize reticuloendothelial tissues (liver, gallbladder, spleen, bone marrow), where bacilli multiply further causing massive bacteremia (occurs towards the end of incubation period) → disease clinically manifests.

- Bile is a good culture medium for typhoid bacillus:

- Bacilli multiply in the gallbladder → bacilli are continuously shed through the bile into the → intestine.

- In the intestine, the bacilli are localized to the Peyer’s patches and lymphoid follicles of the terminal ileum. They cause inflammation, plateau-like elevations of Peyer’s patches and necrosis, which results in characteristic oval typhoid ulcers.

Morphology of Typhoid fever:

Morphology of intestine in typhoid fever.

Lesions may be

- Intestinal and

- Extraintestinal.

Intestinal Lesions:

- Gross:

- Site: The most commonly involved is the terminal ileum but may be seen in the jejunum and colon.

- Appearance: Peyer’s patches in the terminal ileum enlarge into sharply delineated, plateau-like elevations → shedding of mucosa produces → typhoid ulcers. Characteristics of typhoid ulcer:

- Number: Varies.

- Orientation: Oval ulcers oriented along the long axis of the bowel (tuberculous ulcers of the small intestine are transverse).

- The base of the ulcer: It is black due to sloughed mucosa.

- Margins: Slightly raised due to inflammatory edema and cellular proliferation.

- No fibrosis: Hence, narrowing of the intestinal lumen seldom occurs in healed typhoid lesions

Microscopy of Typhoid fever:

- Mucosa: Oval ulcers over the Peyer’s patches.

- Lamina propria:

- Macrophages containing bacteria, red blood cells (erythrophagocytosis), and nuclear debris

- Lymphocytes and plasma cells

- Neutrophils within the superficial lamina propria.

Extraintestinal Lesions:

- Typhoid nodules: Systemic dissemination of the bacilli leads to the formation of focal granulomas termed typhoid nodules.

- These nodules are composed of aggregates of macrophages (typhoid cells) containing ingested bacilli, red blood cells, and lymphocytes.

- They are common in the lymph node, liver, bone marrow, and spleen.

- Mesenteric lymph nodes: They are enlarged due to the accumulation of macrophage, which contains typhoid bacilli.

- Liver: It shows small, scattered foci of hepatocyte necrosis replaced typhoid nodules.

- Spleen: It is enlarged and soft.

- Abdominal muscles: Zenker’s degeneration.

- Gallbladder: Typhoid cholecystitis.

Clinical Features of Typhoid Fever:

- Onset is gradual and patients present with anorexia, abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

- Fever: Continuous temperature rise (step-ladder fever).

- Rose spots: These are small erythematous maculopapular lesions on the skin that fade on pressure and appear on the chest and abdomen, which occur during second or third week.

- Spleen: It is soft and palpable and may be accompanied by hepatomegaly.

Complications of Typhoid fever:

- Intestinal complications: It can be fatal.

- Perforations of ulcer

- Hemorrhage from the ulcer.

- Extraintestinal complications: Encephalopathy, meningitis, seizures, endocarditis, myocarditis, pneumonia, and cholecystitis. Sickle cell disease → susceptible to Salmonella osteomyelitis.

- Carrier state: Persistence of bacilli in the gallbladder or urinary tract may result in passage of bacilli in the feces or urine → causes a ‘carrier state’ → source of infection to others.

Laboratory Diagnosis of Typhoid Fever:

1. Isolation of Bacilli:

- Blood culture: It is positive in the first week of fever in 90% of patients and remains positive in the second week till the fever subsides. Blood culture rapidly becomes negative on treatment with antibiotics.

- Stool cultures: It is almost as valuable as blood culture and becomes positive in the second and third weeks.

- Urine culture: It reveals the organism in approximately 25% of patients by the third week.

2. Other Tests:

- Widal reaction: Classic Widal test measures antibodies against O and H antigens of S. typhi but lacks sensitivity and specificity. Widal test (immunological reactions) become positive from the end of the first week till the fourth week. There are many false-positive and occasional false-negative Widal reactions.

- Other serologic tests: They are available for the rapid diagnosis of typhoid fever with a higher sensitivity.

- Total leukocyte count: It shows leukopenia with relative lymphocytosis. Eosinophils are usually absent.

Viral Hepatitis

Definition of Viral Hepatitis: Viral hepatitis may be defined as a viral infection of hepatocytes that produces necrosis and inflammation of the liver.

Cause of Viral hepatitis:

- Most cases of hepatitis are caused by a group of five separate, unrelated viruses that have a particular affinity on the liver known as hepatotropic viruses (hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, and E).

- All except HBV are RNA viruses.

1. Hepatitis A Virus:

- Hepatitis A virus (HAV): It is a nonenveloped, 27 nm, RNA virus.

- Source of infection: The only source of infection is an acutely infected person.

Mode of Transmission:

- Fecal-oral route by ingestion of contaminated water and foods.

- Incubation period: 3 to 6 weeks (mean ~ 4 weeks).

The outcome of HAV Infection:

HAV causes a mild, benign, self-limited disease acute hepatitis. HAV does not produce chronic hepatitis or a carrier state and fulminant hepatitis develops only rarely.

2. Hepatitis B Virus (HBV): Structure of HBV:

- Hepatitis B virus (HBV): It is a hepatotropic

- DNA virus belonging to the family Hepadnaviridae.

- HBV virion: It is spherical and double-layered.

- Dane particle: It is the complete viral particle/virion.

Genome Of HBV:

It consists of partially double-stranded circular DNA and has four genes.

- HBsAg (S gene): HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen is secreted into the blood in large amounts. HBsAg is immunogenic.

- HBcAg (C gene): The C gene produces two antigenically different products:

- Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg):

- Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg):

- HBV polymerase (P gene):

- HBxAg (X gene):

Source of infection: A human suffering from hepatitis or carrier is the only source of infection.

Mode of Transmission:

- Vertical/congenital transmission: From the mother [who is a carrier for HBV (90% HbeAg+, 30% HbeAg–)] to a child may occur in utero, during parturition, or soon after birth.

- Horizontal transmission: It is the dominant mode of transmission.

- Parenteral:

- By percutaneous and mucous membrane: Exposure to infectious body fluids, through minor cuts/abrasions in the skin or mucous membranes.

- Intravenous route: Though transfusion of unscreened infected blood or blood products. This mode of spread is rare now, because of routine screening of all blood donors for HBV and HBC.

- Close personal contact: Unprotected heterosexual or homosexual intercourse. The virus can be found in semen and saliva.

- Parenteral:

Incubation period: It ranges from 4 to 26 weeks.

Sequelae/Outcome of HBV Infection:

Write a short note on the sequelae of hepatitis B virus infection.

- Acute hepatitis with recovery and clearance of the virus.

- Chronic hepatitis.

- Progressive chronic disease ending in cirrhosis.

- Fulminant hepatitis with massive liver necrosis.

- Asymptomatic carrier state.

- Hepatocellular carcinoma.

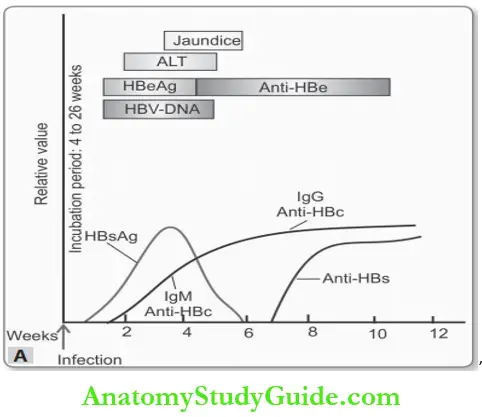

The Sequence of Serological Markers for HBV Hepatitis:

Discuss the laboratory diagnosis (serological markers) of hepatitis B virus infection.

The natural course of the disease can be followed by serum markers:

- HBsAg: It is the first virologic marker

- Significance: Present in the serum in both acute and chronic hepatitis B; indicates an infectious state. Loss of HBsAg plus the development of anti-HBs denotes recovery.

- Anti-HBs: Anti-HBs are a protective antibody present in the serum in the recovery phase and in immunity (i.e. vaccination) and may persist for life providing protection.

- HBeAg, HBV-DNA, and DNA Polymerase They appear in serum soon after HBsAg,

- Anti-HBc: HBcAg is not found in the serum. But its antibody, IgM anti-HBc appears in serum a week or two after the appearance of HBsAg.

Serological findings in HBV are summarized in Table.

Summary of serological findings in HBV:

Prevention: Hepatitis B can be prevented by vaccination and by the screening of donor blood, organs, and tissues. The vaccine is purified HbsAg and induces a protective anti-HBs antibody response.

3. Hepatitis C Virus:

- HCV is a small, enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus. It is a member of the Flaviviridae family.

- Mode of spread: It mainly spreads by the parenteral route as a bloodborne infection. It may also spread by sexual contact.

- Incubation period: 2 to 26 weeks (mean 6 to 12 weeks).

Sequelae/Outcome of HCV Infection:

Sequelae of hepatitis C virus infection.

- Acute hepatitis.

- Chronic hepatitis: It occurs in the majority of individuals infected by HCV. It can be prevented by screening procedures.

- Cirrhosis: It develops over 5 to 20 years in 20 to 30% of patients.

- Fulminant hepatic failure is rare.

4. Hepatitis D Virus:

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is a defective RNA virus, which requires HBV for its replication and expression. Because HDV is dependent on HBV, the duration of HDV infection is determined by the duration of HBV infection.

Patterns of HDV Hepatitis:

HDV causes Delta hepatitis with two clinical patterns.

- Acute coinfection: It develops when an individual is exposed simultaneously to serum containing both HDV and HBV. The HBV infection first becomes established and the

- HBsAg is necessary for the development of complete HDV virions.

- Superinfection: It occurs when an individual is already infected with HBV is exposed to a new dose of HDV.

Mode of spread: Parenteral route and sexual contact.

5. Hepatitis E Virus:

- HEV is an unenveloped, RNA virus in the Hepevirus genus.

- Hepatitis E occurs primarily in young to middle-aged adults.

Source of infection: HEV is a zoonotic disease with animal reservoirs, such as monkeys, cats, pigs, and dogs. Virions are shed in stool during acute illness.

Mode of transmission: It is an empirically transmitted, waterborne infection.

Incubation period: ~6 weeks.

The outcome of HCV Infection: It causes self-limiting acute hepatitis. It does not cause chronic liver disease. But it has a high mortality rate (about 20%) among pregnant women.

Salient features of hepatitis viruses are presented in Table.

Summary of features of hepatitis viruses:

Clinical Features of Hepatitis C Virus:

- Asymptomatic acute infection with recovery (serologic evidence only).

- Acute hepatitis (anicteric or icteric).

- Fulminant hepatitis with massive to submassive hepatic necrosis.

- Chronic hepatitis (without or with progression to cirrhosis).

- Chronic carrier state.

Acute Hepatitis:

- It can be caused by any one of four hepatotropic viruses.

- It presents with nonspecific symptoms such as malaise, nausea, poor appetite, and vague abdominal pain.

- Jaundice and yellow sclera, dark-colored urine (conjugated hyperbilirubinemia), light-colored stool, and pruritis (bile salt retention).

Investigations of Acute Hepatitis:

- Biochemical: Raised serum bilirubin and aminotransferase levels.

- Serology: Hepatitis viral genome in the liver and serum followed by antibodies to viral antigens.

Morphology of Acute and Chronic Hepatitis:

Morphology of liver in viral hepatitis.

General morphological features:

The majority of microscopic changes caused by hepatotropic viruses (A, B, C, D, and E) are generally similar.

Microscopy Acute Hepatitis:

1. Hepatocyte injury:

- Ballooning degeneration: It is characterized by swelling of hepatocytes, empty and pale stained cytoplasm, with clumping of cytoplasm around the nucleus.

- Hepatocyte necrosis: Dropout necrosis: Rupture of the cell membrane of ballooned hepatocytes → leads to cell death and focal loss of hepatocytes → necrotic cell dropout → collapse of sinusoidal collagen reticulin framework → aggregates of macrophage around necrotic hepatocyte.

- Acidophilic or apoptotic or Councilman body: It is caused by anti-viral cytotoxic (effector) T cells. Apoptotic hepatocytes shrink → become intensely eosinophilic and have with a densely staining pyknotic or fragmented nuclei.

- Bridging necrosis: It is a confluent (uniting band/zone) necrosis of hepatocytes observed in severe acute hepatitis. This band/zone of necrosis may extend from portal tract to portal tract, central vein to central vein, or portal-to-central regions of adjacent lobules.

2. Inflammation: It involves all areas of the lobule and is a characteristic and prominent feature of acute hepatitis.

- Mononuclear inflammatory cells: mainly consists of lymphocytes and macrophages.

- Lobular hepatitis: It is inflammation involving liver parenchyma away from the portal tract.

- Interface hepatitis: It can occur in acute and chronic hepatitis.

3. Kupffer cells: They show hypertrophy and hyperplasia.

- Lobular disarray: It is due to a combination of necrosis of hepatocytes, accompanying regeneration, and mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate → disruption of the normal orderly architecture of the liver cell plates.

Chronic Hepatitis

Write a short note on chronic hepatitis.

Definition of Chronic Hepatitis: Chronic hepatitis is defined as symptomatic, biochemical, or serologic evidence of hepatic disease for more than 6 months.

Microscopically, there should be inflammation and necrosis in the liver.

Causes of Chronic Hepatitis:

Hepatitis may be caused by viruses (HCV, HBV, and HDV+HBV) as well as other etiological agents:

Morphology of Chronic Hepatitis:

Microscopy:

It is characterized by a combination of

- Portal inflammation

- Interface hepatitis

- Parenchymal inflammation and necrosis, and

- Fibrosis.

1. Portal inflammation: Predominantly consists of lymphocytes, macrophages, and occasional plasma cells.

Interface hepatitis (piecemeal necrosis/periportal necrosis): It is an important feature characterized by the spillover of inflammatory cells (lymphocytes and plasma cells) from the portal tract into the adjacent parenchyma at the limiting plate → associated with degenerating and apoptosis of periportal hepatocytes.

3. Parenchymal inflammation and necrosis.

4. Fibrosis: It is the hallmark of chronic liver damage. Continued inflammation and associated necrosis → lead to progressive fibrosis at the limiting plate and enlargement of the portal tract.

Consequence of Chronic Hepatitis:

Continued loss of hepatocytes and fibrosis → results in cirrhosis.

Fulminant Hepatic Failure:

Definition Fulminant Hepatic Failure: Hepatic insufficiency progresses within 2 to 3 weeks from onset of symptoms to hepatic encephalopathy, in patients who do not have chronic liver disease.

Actinomycosis

Define Actinomycosis.

- It is a chronic suppurative disease caused by the anaerobic bacteria, Actinomycetes israelii. It is not a fungus.

- The organisms are commensals in the oral cavity, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and vagina.

- Mode of infection: Infection is always endogenous in origin and not due to personal contact.

- Break in mucocutaneous continuity, and diminished immunity due to some underlying disease favor the organism to invade, proliferate, and disseminate.

Morphology of Actinomycosis:

Depending on the anatomic location of lesions, actinomycosis is divided into four types:

1. Cervicofacial actinomycosis:

- It is the most common form (60%) and has the best prognosis.

- Infections gain through tonsils, carry teeth, periodontal diseases, or trauma following extraction of the tooth.

- In the beginning, a firm swelling develops in the lower jaw (i.e. lumpy jaw). Later, the mass breaks down and forms abscesses and sinuses. Typically the sinus discharges yellow

- Sulfur granules. The infection may spread into the adjacent soft tissues and may destroy the bone.

2. Thoracic actinomycosis:

- The infection of the lung is a result of aspiration of the organism from the oral cavity or an extension of infection from abdominal or hepatic lesions.

- Initially, lung lesions resemble pneumonia but as the disease progresses it spreads to the whole lung, pleura, ribs, and vertebrae.

3. Abdominal actinomycosis:

- The common sites are the appendix, cecum, and liver.

- The infection occurs as a result of swallowing of the organism from the oral cavity or as an extension from the thoracic cavity.

4. Pelvic actinomycosis: It develops as a complication of intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUCDs).

Microscopy of Actinomycosis:

The following features are seen irrespective of the location of actinomycosis:

- Granulomatous reaction with central suppuration: There is a formation of abscesses in the center of lesions and the periphery of the lesions shows chronic inflammatory cells, giant cells, and fibroblasts.

- The central abscess contains a bacterial colony (Sulfur granule) characterized by radiating figments (called ray fungus) surrounded by hyaline, eosinophilic, club-like ends that represent immunoglobulins.

- Special stains for bacteria: The organisms are gram-positive filaments and nonacid-fast.

- They stain positively with Gomori’s methenamine silver (GMS) stain.

Leave a Reply