Developmental Assessment

Children, as opposed to adults, are characterized by a continuous process of physical growth and neuromotor development.

Table of Contents

The maturation of the central nervous system is characterized by the coordination of motor activity and as infants grow they purposefully respond to their environment with the help of special senses (touch, smell, taste, vision, acoustic and auditory inputs), the integrity of labyrinthine, vestibular and musculoskeletal systems.

Read and Learn More Pediatric Clinical Methods Notes

Children achieve neuromotor milestones of development at predictable ages within a narrow range of a few weeks or months.

Development is dependent upon an interaction between innate genetic potential and environmental factors, like emotional security, love, attention, stimulating home environment, optimal nutrition, gender of the child, and ethnic and cultural factors.

When home conditions are unsatisfactory children reared in orphanages and foster homes are likely to have a slower rate of neuromotor development due to a lack of environmental stimulation.

Neuromotor retardation may occur due to gestational immaturity, perinatal hypoxia, birth trauma, metabolic disorders (inborn errors of metabolism), hypoglycemia, kernicterus, intrauterine infections, postnatal CNS infections, hypothyroidism, developmental and chromosomal disorders.

Principles Of Development

- It is the most distinctive attribute of children and is a continuous process from conception to maturity.

- Development is intimately related to the maturation of the central nervous system.

- The sequence of development is identical in all children but the rate of development varies from child to child.

- The generalized mass activity of early infancy is replaced by specific and subtle individual responses. It is a common observation that when shown a bright object, an infant shows wild excitement by moving the trunk, arms, and legs, and babbling while an older child merely smiles and reaches for the object.

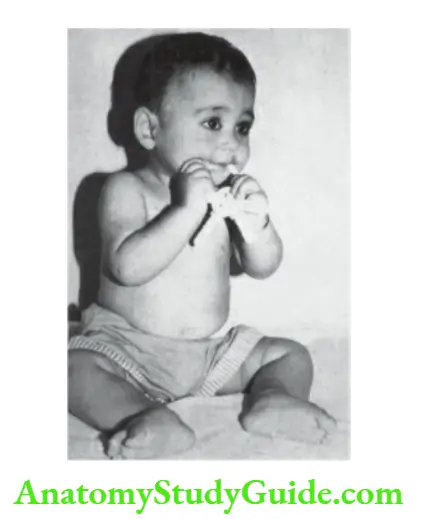

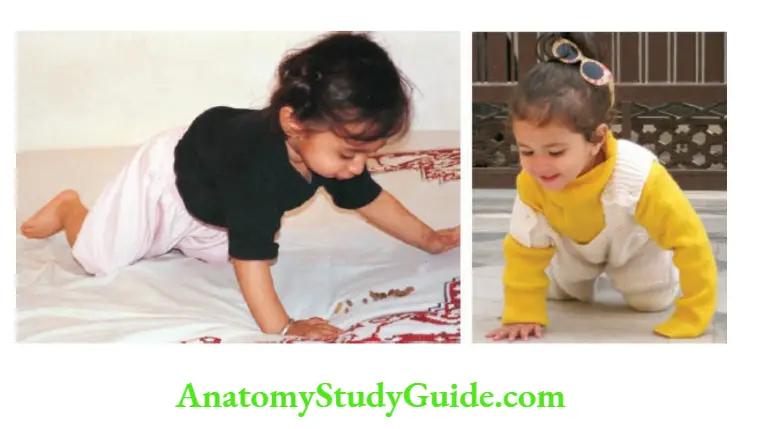

- The development proceeds in a cephalocaudal direction. The infant initially develops head control followed by the ability to roll over and grasp, sit, crawl, stand, and walk.

- Certain primitive reflexes like the grasp reflex and walking reflex must be lost before corresponding voluntary movements are acquired.

- The development of language is early and advanced in girls as compared to boys.

- Timing of dentition is unreliable for the assessment of neuromotor development.

- The child with an odd-looking face does not necessarily have associated mental subnormality.

- attributes, like creativity, future potentiality, various developmental quotients (intelligence, social, emotional, courage, and spiritual), and mental superiority, cannot be predicted in an individual child by developmental assessment.

Methods Of Assessment

A large number of methods have been standardized to assess the development of children. They demand the availability of skilled clinical psychologists and specialized kits for reliable assessment.

Gessel’s development evaluates gross motor, fine motor, social, adaptive behavior, and language.

Amiel-Tisson’s method of assessment pays special attention to muscle tone (active and passive), neurosensory responses (visual and acoustic), and neurobehavioral assessment.

Vineland and Raval’s social maturity scale assesses social and adaptive mental development.

The other methods of neuromotor assessment include Bayley Scales of Infant Development (motor and mental), Brazelton neonatal behavior scale, Vojta technique (postural reactions and central coordination), and Denver developmental screening test (DDST) or Denver II.

Among these, Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) is the most popular and widely practiced.

It requires the services of a highly trained examiner and takes 45 minutes to administer 130 test items covering mental, motor, and infant behavior.

Bayley scales of infant development have been standardized for Indian children up to 30 months of age.

In the community setting, health workers can be trained to screen the development of children by using Baroda Development Screening Tests (BDST), Trivandrum Development Screening Chart (TDSC), and Woodside Screening System Test (WSST).

The Clinical Adaptive Test / Clinical Linguistic and Auditory Milestone Scale (CAT/CLAMS) is a useful parental questionnaire to assess the cognitive and language skills of under-3 children.

The draw-a-man test (Goodenough drawing test) is also a simple and reliable tool for developmental assessment in preschool children.

Binet-Kamath (Stanford-Binet) and Wechsler intelligence scales for children are more sophisticated and can be used in some selected centers.

The developmental quotient can be calculated as follows DQ = developmental age/chronological age x 100.

The quotient can be separately calculated for motor and mental or cognitive development (visual-motor and receptive

and expressive language).

The development is considered as slow or retarded, if the developmental quotient is less than 70.

Basic Bed-Side Tools For Assessment

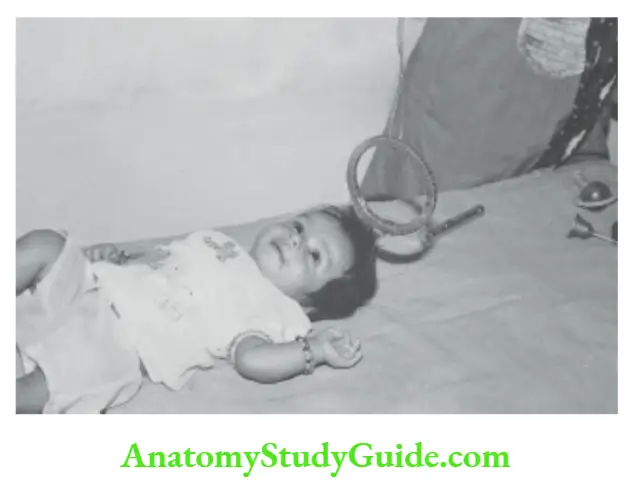

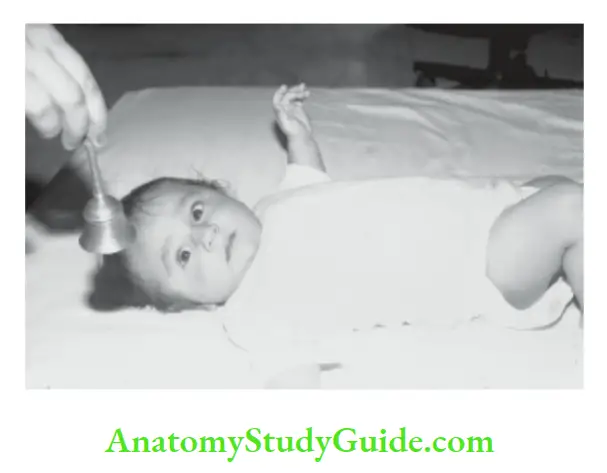

The pediatric resident must acquire simple objects and instruments to undertake bedside assessment of development whenever indicated.

These items include a torch, a dangling red ring of 6.5 cm diameter, a red ball of 5.0 cm diameter, ten 2 to 5 cm sized colorful cubes, a temple bell, a rattle, a cup with a handle, a bunch of keys, pellets or beads, picture book, paper and crayons and percussion hammer.

Indications For Developmental Assessment

- Follow-up of high-risk neonates for early detection of cerebral palsy and/or mental

retardation. - Complete evaluation of children with dysmorphism, developmental, chromosomal and

neurological disorders. - To differentiate children with retardation in specific fields of development as opposed to those with global retardation.

- Evaluation of children with learning disabilities.

Developmental History

An accurate history of developmental milestones is often difficult to obtain due to poor observation and the educational status of the mother.

Early events in the life of a child’s development may be forgotten by the parents. The milestones should be asked in chronological order simply and lucidly.

The social smile must be differentiated from the spontaneous smile which even newborn babies may exhibit during sleep or fantasy. It is not enough to know when the child controlled his head or was able to sit.

It is equally important to know the quality of head control and whether the child can sit without support with a straight back or in a crouched posture.

It is important to ask the mother how the development of the index child compares with his siblings. She can recollect comparisons more readily rather than precise ages for achieving various milestones.

The mother should be asked whether the child interacts and plays with children of his age likes the company of younger children or is self-centered and is lost in his world.

Efforts should be made to identify whether the child is globally retarded or slow only in an individual or specific field, for example, delayed speech in a deaf child, delayed walking in a child with protein-energy malnutrition, or congenital dislocation of hips.

The developmental progress of older children is best evaluated by consideration of school performance, proficiency in games, motor dexterity, and social behavior.

Developmental Milestones

Apart from assessing the developmental milestones, the resident should undertake a detailed neurological examination, and evaluate the muscle tone (adductor angle, scarf maneuver, Landau reflex, parachute reaction, etc.) and special senses (vision and hearing).

All high-risk infants must be subjected to a detailed assessment of hearing and vision at the age of 3 to 6 months.

Factors associated with deafness during infancy include prematurity, meningitis, craniofacial malformations, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, congenital viral infections, kernicterus, prolonged use of aminoglycosides and furosemide, parental consanguinity and family history of deafness.

Developmental Assessment

The child is placed in different postures and positions depending upon his chronological age and assessed for expected developmental responses as given in.

In preterm babies, corrected age (conceptional age calculated from the expected date of delivery) should be used as the chronological age, especially during the first year of life.

Gross Motor Development

Gross motor development is assessed by placing the infant in various postures and positions.

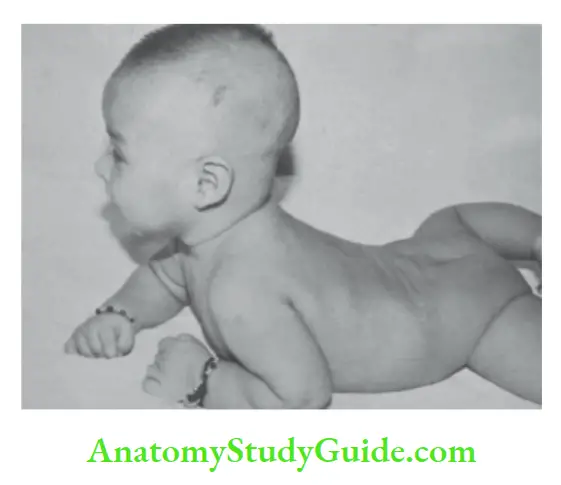

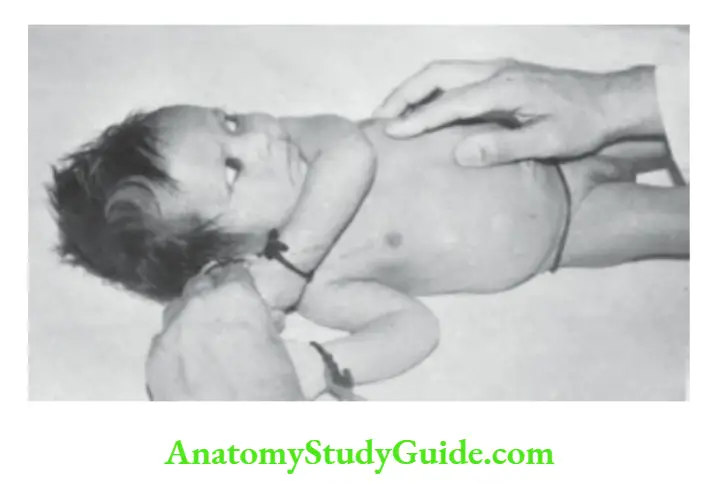

Ventral Suspension

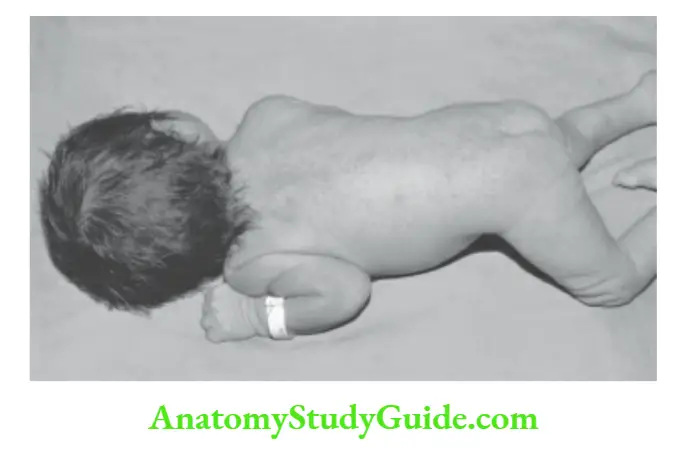

The examiner suspends the infant in a prone position by supporting the abdomen of the baby on his palm. The extension of the neck and flexion of the extremities are observed.

12 weeks: The Pelvis is kept flat on the couch with legs completely extended, and the chin is lifted off the couch.

16 weeks: Chest is maintained off the couch, and arms are stretched out in full extension.

20 weeks: The body weight is supported on the forearms.

24 weeks: Weight is supported on hands, and baby rolls from prone to supine. Indian babies first learn to roll from supine to prone because they are usually nursed in a supine position.

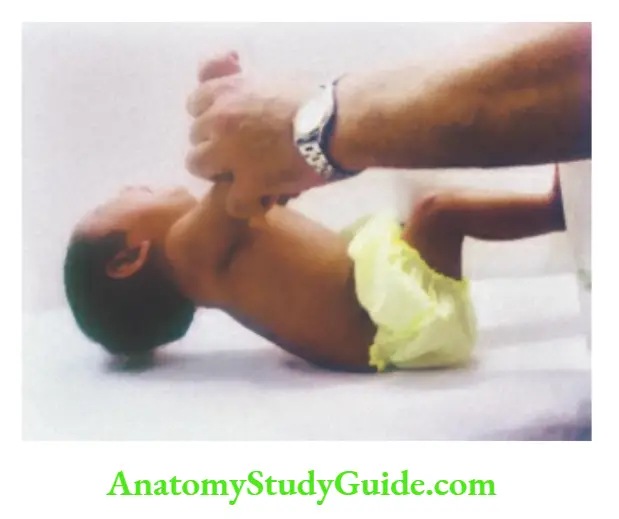

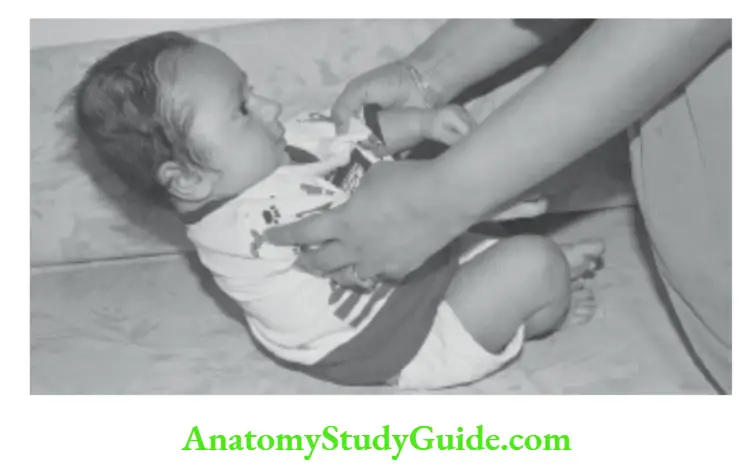

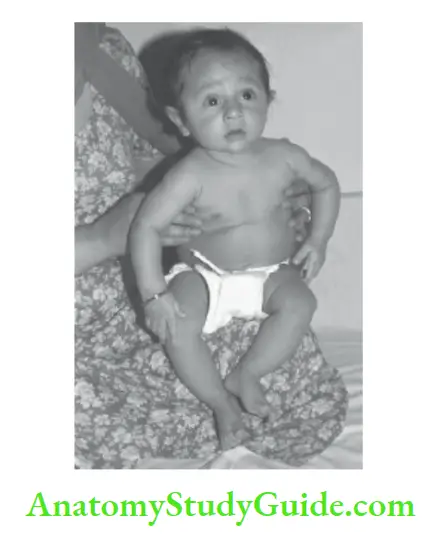

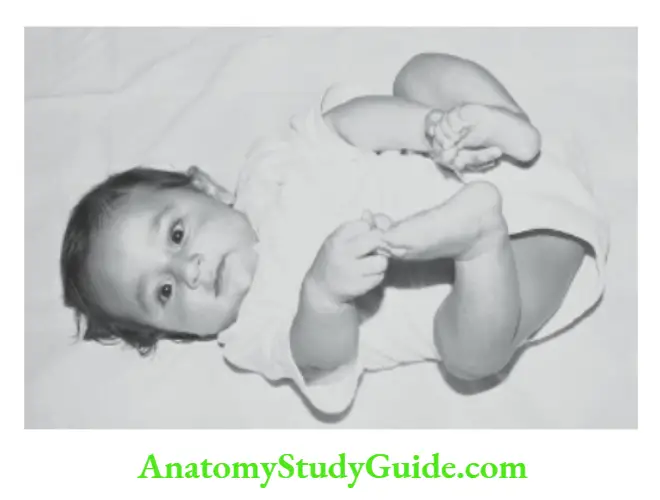

Supine Posture and Sitting

The infant is placed supine on the couch and pulled to a sitting position by lifting at the forearms (traction response).

Newborn: Complete head lag.

4 weeks: Head maintained in the plane of the body momentarily when baby is held in a sitting position, back is rounded. The chin may be lifted up momentarily.

12 weeks: Head held up when supported in a sitting position but it tends to bob forwards.

16 weeks: When pulled up, there is slight head lag during the beginning and then the head is flexed beyond the plane of the body. When held in a sitting position and the baby is swayed, the head wobbles.

20 weeks: No head lag, the head is stable without wobbling and the back is straight.

24 weeks: When about to be pulled up, lifts head off the couch in anticipation. Can sit supported in a pram or high chair.

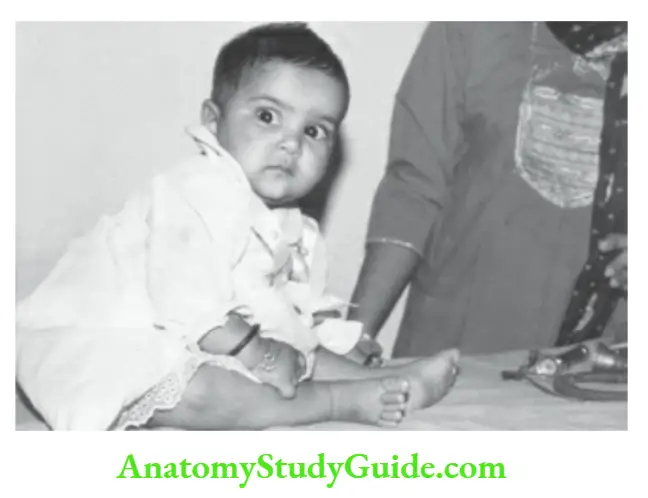

28 weeks: Can sit on the floor with the support of hands

32 weeks: Can sit momentarily on the floor without support.

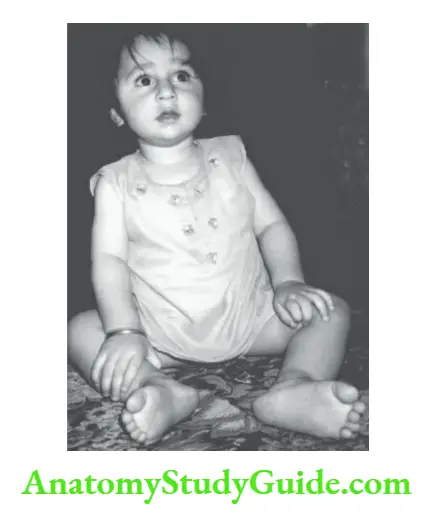

36 weeks: Sits steadily without support and can lean forward and recover his balance.

40 weeks: Can sit up from a supine position.

48 weeks: Can turn sideways and twist around to pick up an object.

Key gross motor milestones

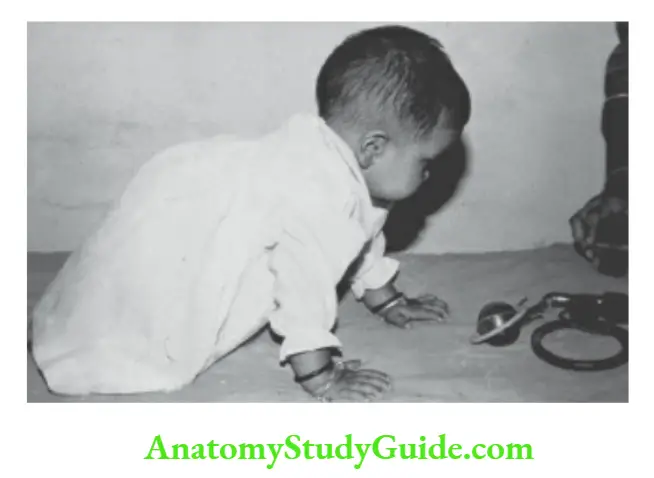

4 months: Stable head control, rolls over, body weight supported on forearms in a prone position

6 months: Sits with support with a round back

8 months: Sits without support with a straight back, can cruise and crawl

10 months: Climbs and stands with support

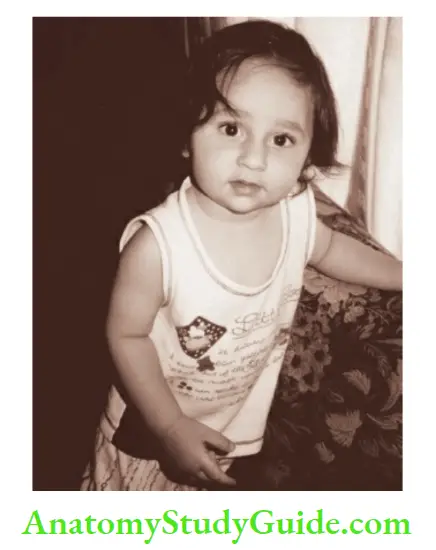

12 months: Stands without support

15 months: Walks without the support and creeps upstairs

18 months: Runs, throws a ball while standing, searches drawers

2 years: Jumps, can walk backward, walks up and downstairs with two feet on each step, able to kick a ball

3 years: Rides tricycle, goes upstairs with one step on each step

4 years: Hop and skip on one foot, come downstairs with one step on each stair

5 years: Skips on both feet, can jump over low obstacles

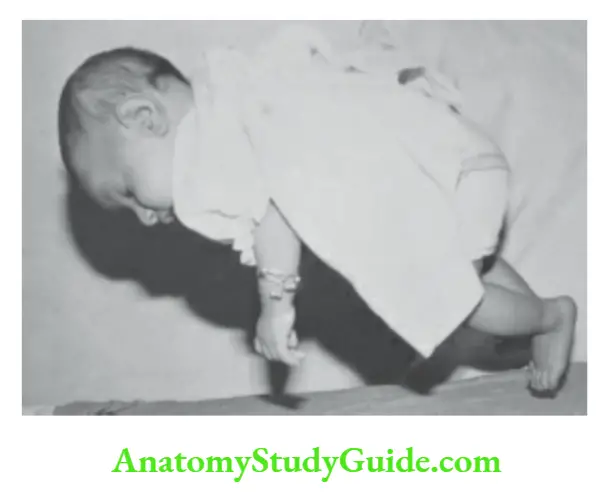

Vertical Suspension, Standing and Walking

Newborn: Walking reflex during first 2 to 3 weeks.

8 weeks: Can hold my head up for some time.

24 weeks: Puts almost all the weight of the body on the legs.

28 weeks: Bounces with pleasure.

36 weeks: Pulls self to stand, and can stand with support.

44 weeks: Lifts one foot while standing.

48 weeks: Walks two hands held or on holding the furniture.

52 weeks: (1 year) Walks a few steps independently.

15 months: Creeps upstairs can kneel without support.

18 months: Runs, can crawl up and down the stairs without help, pulls a wheeled toy

2 years: Walks up and down the stairs with two feet on each step, walks backward on imitation, picks up objects from the floor without falling, and can kick a ball.

2½ years: Can walk on tiptoes and jump on both feet.

3 years: Goes upstairs with one foot on each step and jumps off the bottom step.

4 years: Comes downstairs with one foot on each step and can hop and skip on one foot.

5 years: Skips on both feet and can jump over low obstacles.

Fine Motor, Visual-motor, Problem Solving and social responses (Manipulations)

The newborn Grasp reflex is present.

4 weeks: Hands mostly closed.

8 weeks: Hands kept open more often

12 weeks: Hands mostly open, grasp reflex disappears, plays with a rattle when it is placed in the hand.

16 weeks: Tries to reach objects but overshoots, hands come together during play.

20 weeks: Goes for objects and gets them usually with an ambidextrous approach, puts objects into the mouth, and plays with toes.

24 weeks: Drops one object when another is given, holds rattle, picks up a cube with crude palmar grasp.

28 weeks: Unidexterous approach to objects, transfers object from one hand to the other, feeds self with a biscuit, bangs object with each other or on a tabletop, retains one cube when another is offered.

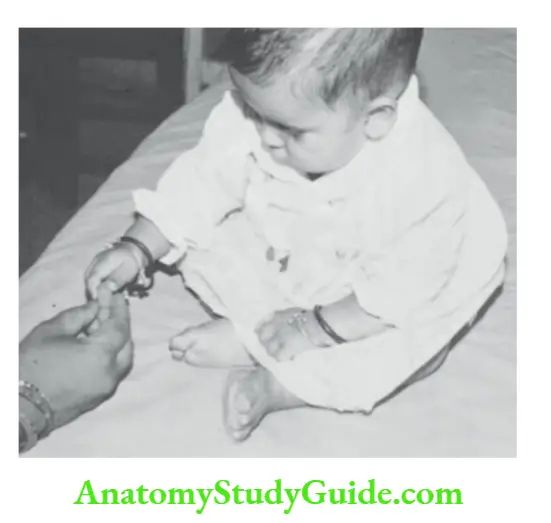

40 weeks: Pincer finger-thumb fine grasp to pick up a pellet.

1 year: Gives toy to the examiner, uses mature pincer grasp, puts one object after another into the basket, mouthing is much reduced.

15 months: Self-feeds with a cup, builds a tower of 2–3 cubes, holds two cubes in one hand, and imitates scribbling.

18 months: Can self-feed with a spoon, makes a tower of 3–4 cubes, and turns 2–3 pages of a book at a time.

2 years: Makes tower of 6–7 cubes, can turn pages one at a time, can turn the door knob, puts on and takes off socks, shoes, and pants.

2½ years: Can hold a pencil in hand to scribble lines.

3 years: Makes tower of 9–10 cubes, can dress and undress, can manage buttons, can draw a circle.

4 years: Copies a square and cross, makes a bridge, can dress self completely, can button the dress, catches a ball.

5 years: Copies a triangle, can tie shoe laces, can spread butter on the toast with a knife.

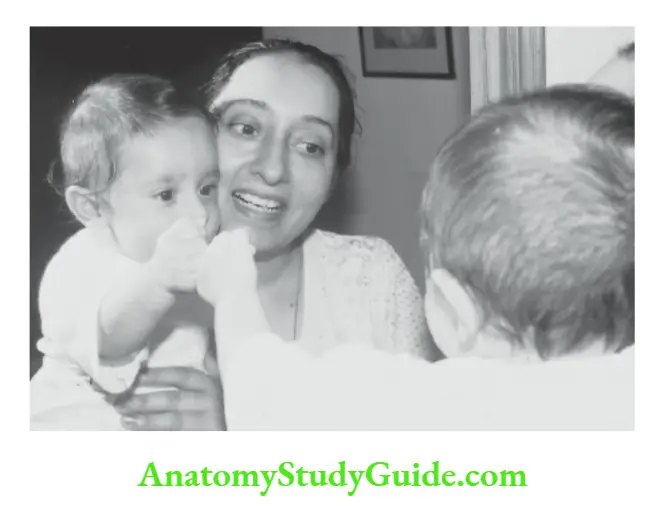

Social, Adaptive, and Language Development

4 weeks: Watches their mother intently when she speaks to him. Follows a dangling object up to 90°, and quietens on the sound of the bell.

6 weeks: Gives an interactive or social smile which should be differentiated from a spontaneous smile which is present even in neonates, follows a moving person

8 weeks: Fixes and focuses gaze, eye-to-eye contact, vocalizes.

12 weeks: Hand regard, recognizes mother, can follow an object up to 180°, babbles when spoken to, squeals with pleasure, and gets excited on seeing a toy.

16 weeks: Demonstrates excitement when feed is being prepared, laughs loud, turns head towards the sound of bell/rattle.

20 weeks: Smiles at a mirror image, imitates simple acts, dry during daytime if toilet trained, stranger anxiety.

24 weeks: No more hand regard, shows displeasure when a toy is taken away, demonstrates likes and dislikes, when an object is dropped he looks for it searchingly.

28 weeks: Imitates actions and sounds, enjoys “peek-a-boo” and “pat-a-cake” games, responds to names, pats mirror image, says monosyllables, like ba, da, ma.

32 weeks: Imitates sounds, responds to ‘No’, produces disyllables, like ma-ma, ba-ba, da-da, etc.

Key language milestones

1-month: Quietens or alerts to sound

3 months: Babbles and coos when spoken to

4 months: Laughs loudly, turns toward the sound

6 months: Speaks monosyllables, like ba, da, pa, ma, and ah-goo sounds

9 months: Utter’s disyllables, like mama, papa, dada

12 months: Speaks 2–3 words with meaning

18 months: Jargon speech with 7–10 words of vocabulary

2 years: Can make 2–3 word sentences with a vocabulary of 50 words, can repeat what is said, use pronouns “I’, “me”, “you”

3 years: Can make 3-word sentences and has a vocabulary of 250 words, normal speech, asks questions

4 years: Can tell a story, recite a poem, or sing a song, inquisitive

5 years: Chatterbox and asks the meaning of words

40 weeks: Pulls clothes of mother to attract attention, waves bye-bye, repeats performance which is laughed at.

1 year: Gives toy to the examiner, uses mature pincer grasp, interested in the picture book, comes when called, imitates actions, shakes head for ‘No’, says 2–3 words other than mama/pa-pa with meaning.

1½ year: Jargon speech, 10–15 words vocabulary, indicates the need for potty and when undergarments are wet, knows 5 body parts.

2 years: Repeats what is said, uses the words ‘I’, ‘me’, and ‘you’, ask for food, and drink, and tells the need for the toilet. Lisping and some stuttering are common and can use two-word sentences with a vocabulary of 50–100 words

3 years: Normal speech, with 3-word sentences with a vocabulary of 250 words, attends to toilet needs except for wiping, can dress and undress, knows his name, age, and gender

4 years: Knows colors, develops right and left discrimination, can sing a song and recite a poem, asks questions, can tell a story, can cooperate to play in a group, goes to the toilet alone

5 years: Identifies 4 colors, asks for meaning of words, plays competitive games, abides by rules, likes to help in household tasks

Vertical Suspension, Standing and Walking

Newborn: Walking reflex during first 2 to 3 weeks.

8 weeks: Can hold my head up for some time.

24 weeks: Puts almost all the weight of the body on the legs.

28 weeks: Bounces with pleasure.

36 weeks: Pulls self to stand, and can stand with support.

44 weeks: Lifts one foot while standing.

48 weeks: Walks two hands held or on holding the furniture.

52 weeks: (1 year) Walks a few steps independently.

15 months: Creeps upstairs can kneel without support.

18 months: Runs, can crawl up and down the stairs without help, pulls a wheeled toy

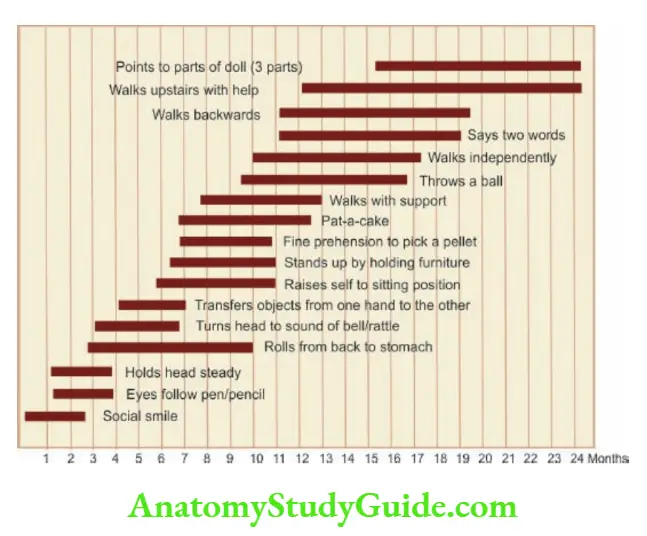

Target Milestones

The developmental milestones are achieved by healthy normal children within a narrow range of several weeks.

The recommended corrected ages (calculated from the expected date of delivery) for undertaking developmental assessment are 4 months, 8 months, 12 months, and then every 6 months till 3 years of age.

The upper age limits for the achievement of some of the target milestones are given in B. The children with red alerts should be subjected to a detailed developmental assessment by an experienced developmental psychologist.

For assessment of hearing and vision refer to Chapters 14 and 15.

Early Markers Of Cerebral Palsy

The high-risk newborn babies should be followed up for early identification of neuromotor disability so that appropriate stimulation therapy can be initiated to enhance neuromotor development.

The mother can be taught by the therapist to use simple culturally acceptable interactions to provide stimulation to the child.

The child should be stimulated by music, bright-colored objects, lullabies, and interactive overtures of the mother. It must be realized that the mother is the best therapist and teacher for her infant.

She should caress, touch, tease, talk, sing, tell stories, and respond to the child’s pranks. The following clinical markers should be looked for to make an early diagnosis of cerebral palsy.

Red alerts

- Lack of social smile by 2 months

- Absence of stable head control for 4 months

- Inability to recognize the mother by 6 months

- Inability to sit when pulled to sit by 6 months and lack of independent sitting without support by 8 months

- Lack of creeping or crawling by 9 months

- Inability to stand without support for one year

- Inability to walk without support by 18 months

- Lack of pincer or thumb-index finger grasp by the age of one year

- Inability to play interactive games (peek-a-boo, pat-a-cake) by the age of one year

- Absence of disyllabic babbling by the age of one year and failure to make meaningful sentences by 3 years of age

- Episodes of inconsolable crying, chewing movements, lip smacking, excessive sensitivity to light and noise, spontaneous or excessive startle, and Moro response.

- Persistent neck tonic posture beyond 4 weeks of age.

- Clenched fists with thumbs adducted and flexed across the palm beyond 8 weeks.

- Paucity or absence of fidgety limb movements during the first 6–12 weeks.

- Abnormalities in tone (usually hypertonia but occasionally hypotonia) as assessed by scarf signs and various angles.

- Persistence of automatic reflexes beyond 5–6 months (Moro reflex, grasp reflex, asymmetric tonic neck reflex).

- Persistent asymmetry of posture, tone, movements, and reflexes is abnormal.

- Slow head growth.

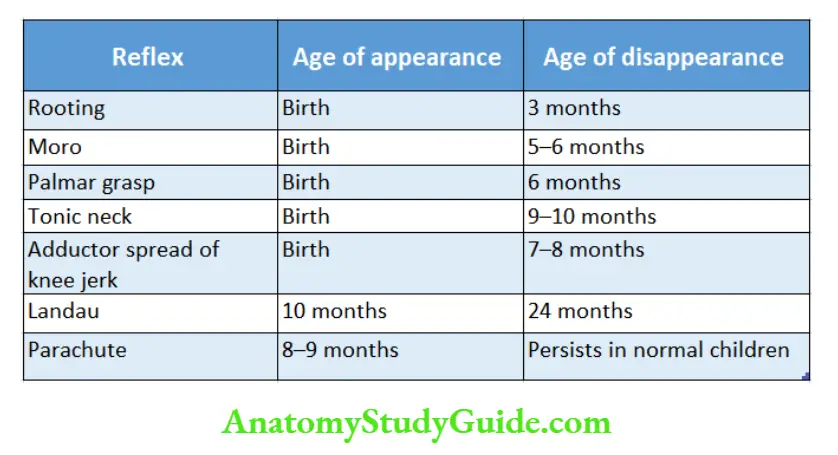

Gives ages at appearance and disappearance of common primitive or automatic reflexes.

The absence of parachute response and Landau reflex and persistence of other automatic reflexes beyond the ages mentioned are indicative of cerebral palsy.

Assessment of Muscle Tone

Alterations in muscle tone especially hypertonia is common in cerebral palsy. Healthy-term newborn babies have physiological hypertonia and there is a gradual reduction of muscle tone during the first year of life.

Muscle tone should be assessed when the baby is alert, wide awake, not hungry or crying, and should lie supine with the head in the midline. The muscle tone is evaluated by

- Looking for an abnormal posture of the limbs,

- Palpation of muscles for a flabby or firm feel,

- Range of movements and resistance encountered at major joints and

- By shaking the unsupported limb for range and facility or stiffness of movements.

The range of movements at Major joints is tested during infancy as follows:

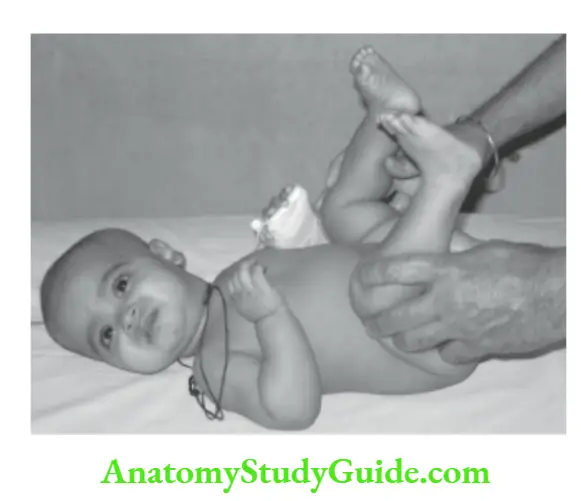

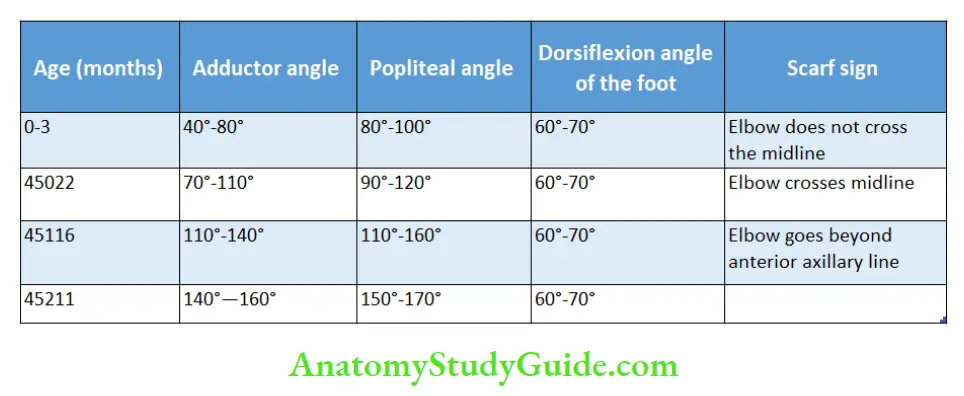

Adductor angle

The infant lies supine with legs extended and head in the midline. Both the hips are abducted maximally by holding at the knees with the index finger resting over the front of the thighs. The angle between the thighs is the adductor angle.

The adductor angle is narrow and resistance is encountered during the procedure when the infant is hypertonic. Asymmetry between the right and left leg should be noted.

Popliteal angle

The infant lies supine on the cot. The hips are flexed completely onto the abdomen by holding at the knees.

The legs are then extended by gentle pressure with the examiner’s hands placed behind the legs and the popliteal angle is measured.

The resistance encountered to the maneuver is noted on both sides. The angle is measured separately on two sides.

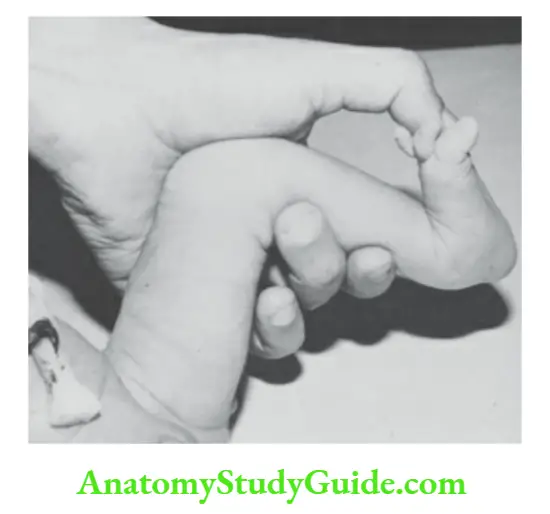

Dorsiflexion angle of the foot

The foot is passively dorsiflexed by applying gentle pressure with the thumb placed over the sole. The angle between the dorsum of the foot and the front of the leg is noted. During infancy, the dorsiflexion angle at the ankle is 70° or less.

Heel-to-ear maneuver

With the infant lying supine, legs extended at the knees are held together and lifted as far backward as possible towards the ears without lifting the pelvis from the table.

Increased resistance on one side is suggestive of asymmetry of tone on the two sides.

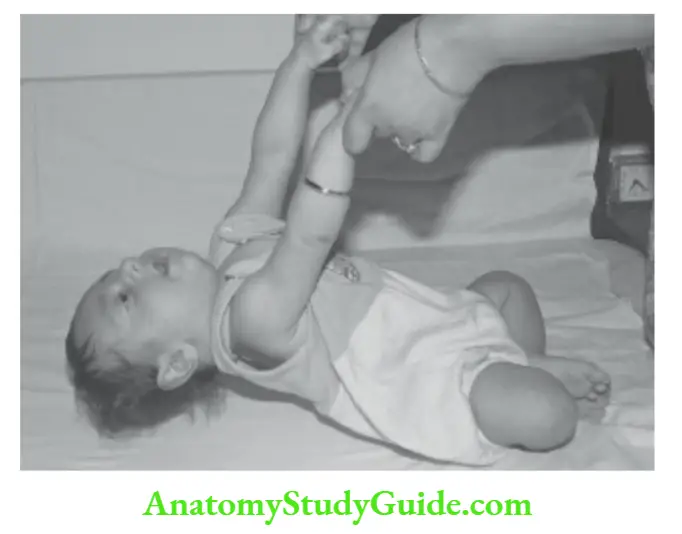

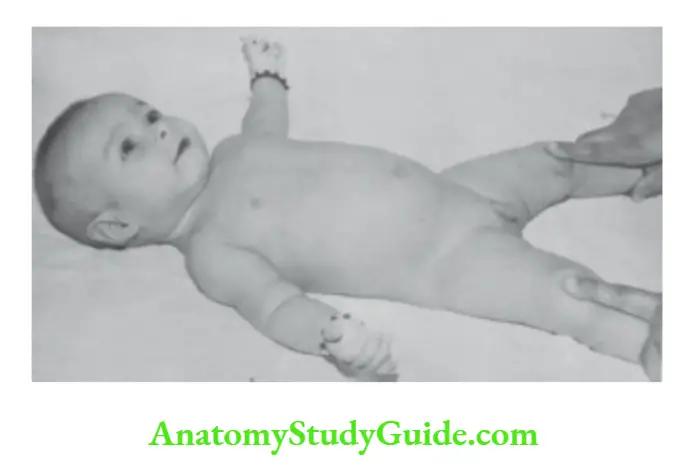

Scarf sign

The muscle tone in the upper limbs is tested by assessing the range of movements at the shoulders.

The infant lies supine on the cot. The upper limb, flexed at the elbow, is pulled as far as possible across the chest by holding at the hand and wrist. The position of the elbow in relation to the midline of the body is noted.

One limb is tested at a time followed by both limbs together. The normal range of various angles during infancy is given in.

Transitory abnormalities in muscle tone (especially hypotonia) may be noted during the first six months of life and they normalize by the age of one year.

Method to assess the scarf sign. One arm at a time is held by the wrist and pulled across the chest towards the

opposite shoulder. The position of the elbow is noted against the plane of the trunk. The head should be kept in the midline while assessing tone in infants.

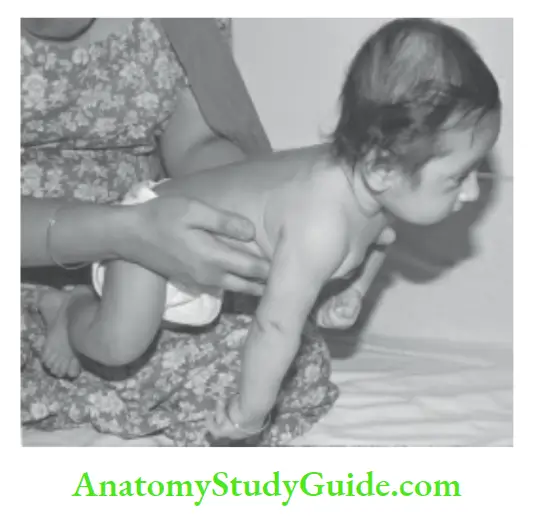

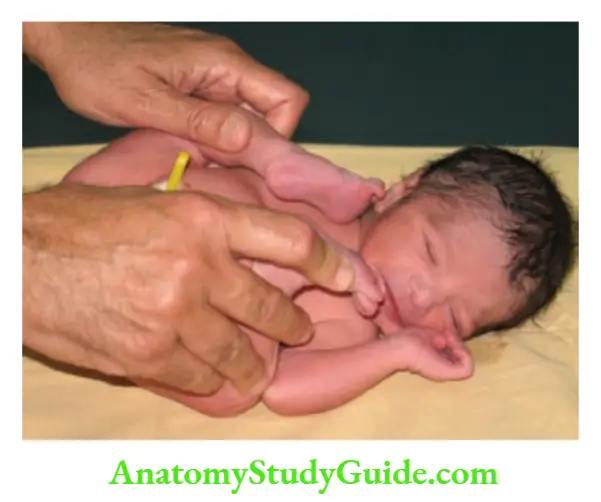

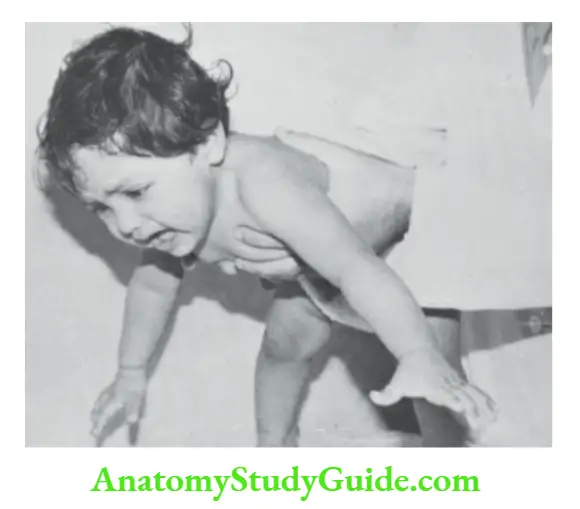

Parachute response

Hold the child in the prone posture with both hands by the waist and suddenly lower him over a tabletop. There will be brisk extension and abduction of the upper limbs with an extension of fingers as if to break the fall.

It is a protective reflex and appears around 8 to 9 months of age. The reflex is absent in infants with spastic type of cerebral palsy.

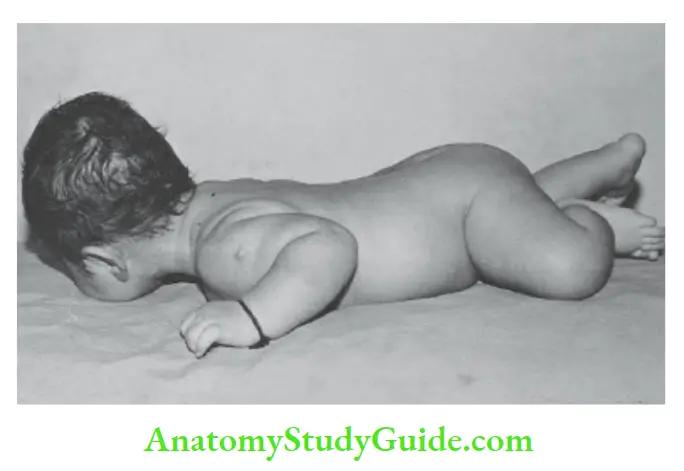

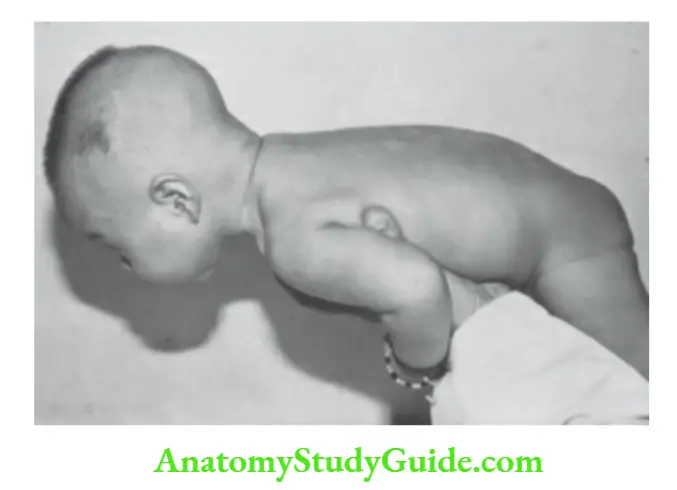

Landau reflex

The infant is suspended in the prone position by supporting the abdomen of the baby on the palm. The infant spontaneously extends the neck, trunk, and legs after the age of 10 months.

Forcible flexion of the neck is associated with flexion of hips and legs. The reflex is absent, if there is a disorder of muscle tone especially in floppy infants.

Developmental Screening Tools

A number of parent-completed questionnaires are available for developmental screening like parent’s evaluation of developmental status (PEDS) and ages and stages questionnaire (ASQ).

A simplified Developmental Assessment Tool for Anganwadis (DATA) has been introduced for the screening of toddlers between 18 and 36 months of age by the Anganwadi workers.

Sophisticated developmental testing instruments are time-consuming and require the services of a trained developmental psychologist. They are useful for the detection of borderline abnormalities as well as for research purposes.

There is a need to develop reliable simple developmental charts which can be used by a busy clinician or medical health worker in the community.

The ideal development screening tool should be reliable, simple, easy to administer, time-efficient, cost-effective, and culturally relevant.

Trivandrum Developmental Screening Chart (TDSC)

It is suitable for the developmental screening of children below 2 years by a paramedical health worker. The range of each test item has been taken from the norms obtained on the Bayley scales of infant development.

It is based on 17 simple test items carefully chosen from among 67 motor items of Bayley scales of infant development (Baroda norms).

The left-hand side of each horizontal dark line represents the age at which 3 percent of children passed the item and the right edge represents the age at which 97 percent of the children passed the item in studies conducted at Trivandrum.

A plastic ruler or a pencil is kept vertically at the level of the chronological age of the child being tested.

If the child fails to pass any item that lies to the left side of the age marker, the child is considered to have a developmental delay.

It is simple to use and takes 5 to 7 minutes to administer. It is best suited to use in infants around one year of age because most of the test items are concentrated around that age period.

Baroda Development Screening Test (BDST)

To simplify the Bayley scales of infant development, 22 motor items and 31 mental items, not requiring any standardized equipment have been retained.

These items were grouped age-wise, one monthly in the first 12 months and 3-monthly thereafter till 30 months. The 50 percent and 97 percent age placement of each item have been plotted on a graph and joined to have two smooth curves.

The total number of the items passed by a child is plotted against his chronological age (or corrected age if preterm).

When this point falls below the 97 percentile curve, the child is considered to have developmental delay and is subjected to detailed assessment.

Interpretation Of Developmental Findings

1. The developmental delay in two or more spheres (motor, adaptive, social, language, etc.) is called global delay and is suggestive of mental retardation. Based on global developmental status, the mental status or cognition can be clinically graded into dull normal,

educable in an ordinary school, educable in a special school, trainable but not educable.

2. Isolated delay:

in development may occur in a single skill (DQ <70), for example, isolated delay in walking due to congenital dislocation of hips, rickets, neuromuscular disorder, or delay in

3. Deviancy: is defined as atypical development within a single stream when a milestone may be skipped or occur out of sequence the child may crawl without sitting or walk before crawling. It may cause anxiety to parents but is of no significance.

4. Dissociation is defined as a significant difference in the rate of development between two streams of skills.

For example, there may be a dissociation between motor and cognitive development in children with cerebral palsy (motor delay more than cognitive), mental retardation (cognition is delayed more than motor development) or motor milestones may be delayed without any significant adverse effects on cognition, benign congenital hypotonia, protein-energy malnutrition, and rickets.

In children with autism spectrum disorder, gross motor development is usually normal while language development and communication skills may be grossly delayed.

5. Developmental regression is diagnosed when a child loses previously acquired skills or milestones.

The neuromotor regression may be sudden in onset or insidious and slowly progressive.

The common causes of developmental regression include unrecognized head trauma, CNS infection, autism spectrum disorder, infantile myoclonus (hyper), degenerative disorders of the central nervous system, and post-vaccinal reactions (whole cell pertussis vaccine, sheep brain antirabies vaccine).

6. Apart from the integrity of the central nervous system, neuromotor unit, and adequacy of nutrition, environmental stimulation through special senses (vision, hearing, touch, taste, and smell) is essential for the promotion of normal development.

Lack of environmental stimulation and poor interaction between the child and working parents may adversely affect the process of development.

Children in orphanages, with divorced parents, parental discord, or out-of-wedlock are likely to have delayed neuromotor development or behavior disorders.

7. Children with developmental disorders are at an increased risk of manifesting behavior disorders. For example, temper tantrums, and disruptive or introverted behavior may be a manifestation of language delay

8. Children with developmental disorders are at an increased risk of manifesting behavior disorders.

For example, temper tantrums, and disruptive or introverted behavior may be a manifestation of language delay.

Children with autism spectrum disorder (pervasive development disorders) must be differentiated from children with mental retardation. The disorder is 4 times more common in boys than girls.

Autistic children may have normal development up to a certain age and then regress especially in their social and communication skills.

The manifestations are usually evident between 12 and 18 months of age. Autistic children do not like to be held or cuddled and they have no or brief eye contact.

They lack emotional warmth and social interaction. They may have stereotyped, compulsive, and repetitive movements, like rocking, bouncing, head banging, swinging, spinning objects, and flapping or twisting their hands and fingers.

They are lost and engrossed in their world. The child may not respond to his name when called. The child may be fascinated by visual stimuli like moving lights and fans.

Other behavior abnormalities include toe walking, sniffing, licking, or smelling objects. Speech may be absent or they may have a gibberish and repetitive (echolalia) language of their own.

They may have intense liking or possessive behavior regarding some inanimate object and violently react to any change in their environment and daily routines.

Some children may have severe sleep problems. They may have associated mental subnormality and seizure disorder.

The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT-Râ„¢), a 23-item validated autism screen, is widely used to screen children between 16 and 30 months.

Patients with fragile X syndrome, congenital rubella syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, and Rett syndrome may have some autistic mannerisms. The salient or key features of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are listed in the.

9. Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may have learning disability and school problems due to hyperactivity and poor attention span.

The developmental milestones are usually normal and some children may have exceptional cognitive abilities. They are unable to sit still and are perpetually “on the go”.

They are constantly on the move, fidgeting, squirming, and aimlessly touching and poking their fingers into everything.

They have trouble completing their homework assignment, often forgetting and losing track of their personal belongings. They are unable to sit through a television program or listen to a story.

They have short attention spans with poor school performance. They have trouble completing their homework assignment, often forgetting and losing track of their personal belongings.

They have impulsive behavior, blurting out answers before the completion of questions, and have trouble waiting for their turn.

Their behavior becomes worse in crowded places and front of guests. They demonstrate temper tantrums and crying episodes on minor pretexts.

They are aggressive in their behavior and uncooperative with their classmates and have difficulty cultivating friendships.

They may have antisocial behavior, like disobedience, defiance, lack of discipline, destructiveness, fire setting, and inflicting harm to others.

They have associated language and learning disability due to distractibility and short attention span. They are likely to have sleep disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

The diagnosis is facilitated by using the Conners parent rating scale-revised: Short form (CPRSR:S), Conners teachers rating scale-revised short form (CTRS-R:S), and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV (DSM-IV) are available for objective evaluation of children with.

10. Some children may have specific learning disabilities in the fields of reading (dyslexia), writing (dysgraphia), communication, or mathematical (dyscalculia) abilities despite having normal neuromotor development, normal cognition, and social interactions.

Checklist For Autism Spectrum Disorder

- No babbling by 12 months, no meaningful single word by 16 months, no two-word phrases by 24 months.

- Speech may be absent, gibberish, and repetitive (echolalia) language of their own.

- Regression or loss of language or social skills at any age.

- No gestures by finger-pointing or saying bye-bye by one year.

- No pretend playing or make-believe games.

- Short attention span.

- No eye contact.

- Lack of response when his name is called from behind at one year of age.

- Mostly self-occupied with no interest in making friends.

- Repetitive behavior, like throwing of toys, rocking, flapping or twisting of hands, head banging, rocking, bouncing, swinging, spinning objects, asking repetitive questions, etc.

- Resistance to change in an established routine or ritual.

- Limited or lack of facial expression.

- Limited gestures or non-verbal communication.

- They are likely to have the habit of toe-walking, sniffing, licking, or smelling objects.

- They have relative insensitivity to pain.

The Child With A Learning Disability

The learning disability may be due to mental subnormality, visual, auditory, or motor handicaps, emotional disturbances, and lack of stimulation because of environmental disadvantages.

There may be a specific learning disability, like difficulty in understanding written or spoken language or a child may have problems with attention span, listening, thinking, reading, speaking, writing, spelling, and athematics due to perceptual handicaps, dyslexia, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Due to a learning disability and poor academic performance at school, the child may present with psychological or behavioral problems including disruptive, aggressive, hyperactive, withdrawn, lazy, labile, and immature behavior.

Assessment of children with learning problems is a multidisciplinary effort involving the pediatrician, ophthalmologist, audiologist, speech therapist, child psychologist, social worker, and special educator or counselor.

The teacher’s detailed report, parental perceptions and expectations, and the child’s view of his problem should be sought.

A detailed medical history should be taken regarding perinatal events, gestation, birth weight, Apgar score, and neonatal course.

History of any serious or significant medical illness should be sought. Family dynamics, parental discord, and time spent by parents’ interactions with the child should be assessed.

A detailed physical and neurological examination must be done to identify any dysmorphism, or abnormalities in the shape and size of the head.

The presence of soft neurological signs, like the asymmetry of muscle tone, difficulty in standing on one foot, inability to perform rapid alternating movements, difficulty with right-left orientation, clumsiness, poor handwriting and

graphesthesia should be looked for.

The child should be specifically screened for visual acuity and hearing. A detailed psychological assessment is mandatory to assess cognition, perceptual deficit, communication, and social abilities.

Several specialized tests are available for the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), dyslexia, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Refer to Appendices XXXI and XXXII for screening of children for ASD and ADHD.

Leave a Reply