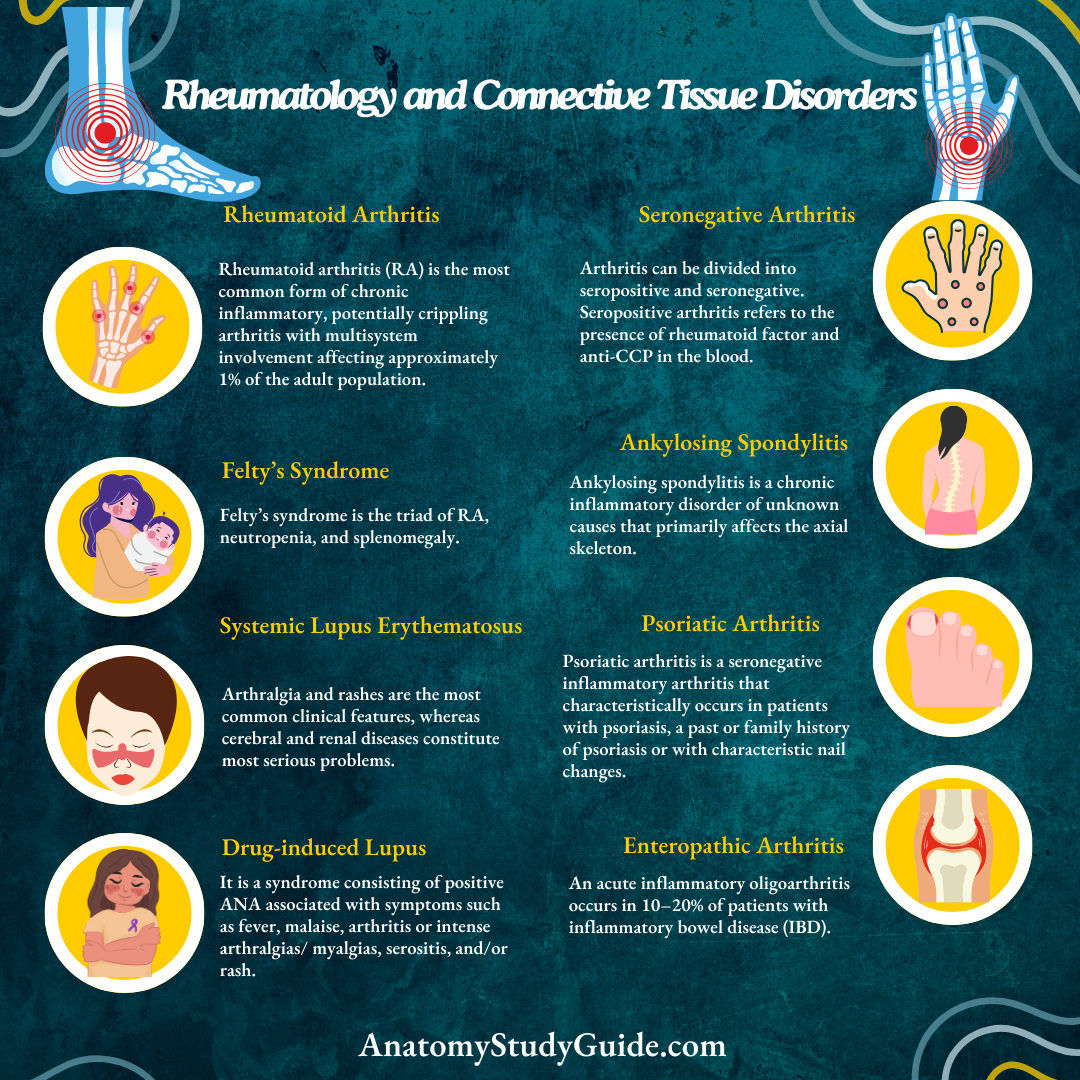

Rheumatology and Connective Tissue Disorders

Introduction:

Question 1. Develop a systematic clinical approach to joint pain based on pathophysiology.

(or)

Prioritize based on clinical features for arriving at an etiological diagnosis in polyarthritis.

Answer:

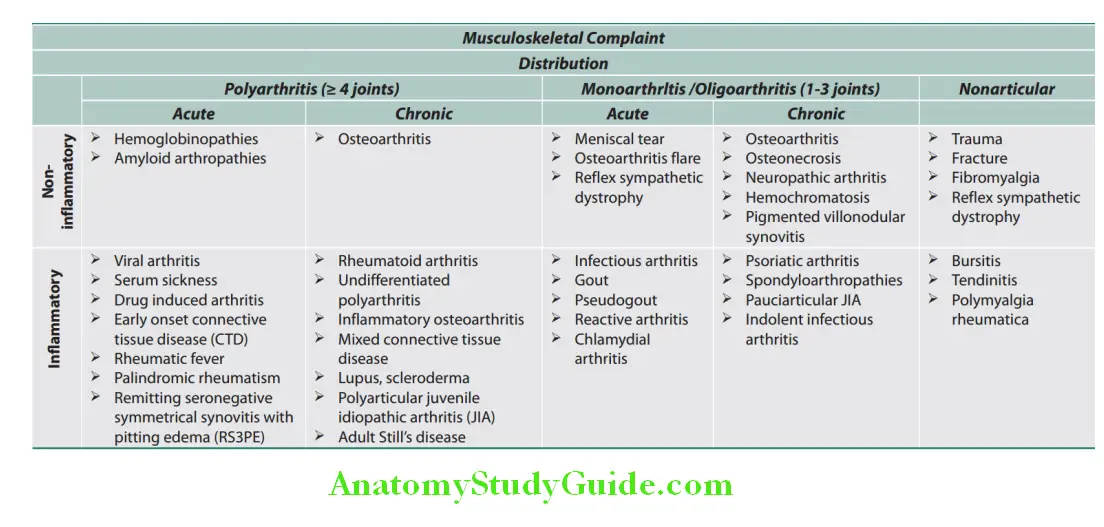

Clinical approach to polyarthritis is important and the diagnosis is often challenging due to the extensive differential diagnosis. Thorough history and physical examination is the cornerstone for diagnosis. The clinical factors helpful in narrowing the diagnosis are the chronology of symptoms, features of inflammation, joint distribution, extra-articular manifestations, disease course and patient demographics.

- Chronology:

- Acute polyarthritis may be due to a self-limited disease.

- It could be due to infectious, crystal induced or reactive causes.

- Rarely chronic polyarticular arthritides, like rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can have acute presentation in the early course of illness.

- Chronic arthritis may be due to immunologic arthritides like RA, noninflammatory and nonarticular causes.

- Inflammation:

- Features of inflammation make it inflammatory arthritis and in the absence it is called athralgia.

- Erythema, warmth, pain and swelling are the cardinal features of inflammation. Fatigue, fever and weight loss can also be present.

- Morning stiffness lasting for longer than an hour is another clue.

- Palpate the joint capsule for synovial thickening, soft tissue swelling effusions.

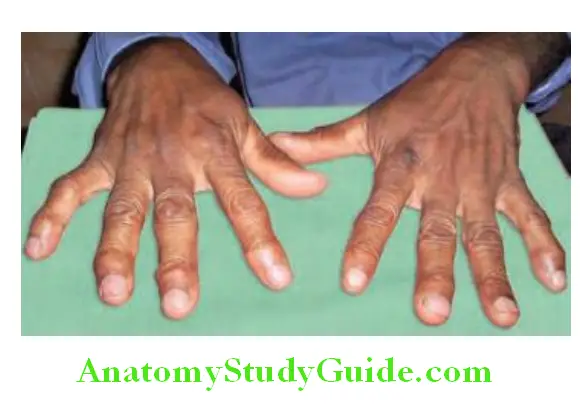

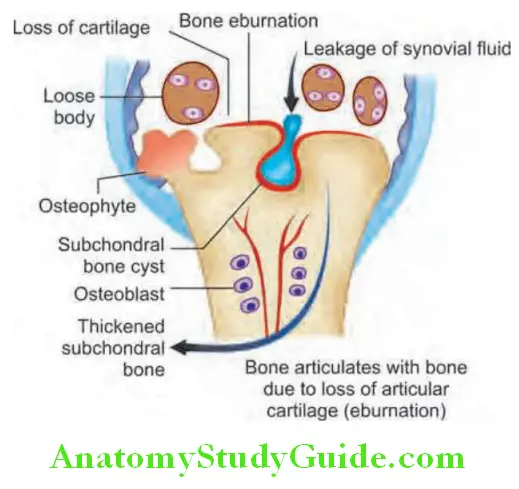

- Presence of crepitus indicates underlying injury, osteoarthritis (OA) or previous inflammation. Heberden’s and

Bouchard’s nodes indicate osteoarthritis. - Subjective sense of swelling without objective sign of synovitis is seen in patients with fibromyalgia.

Question 2. Determine the potential causes of joint pain based on the presenting features of joint involvement.

Answer:

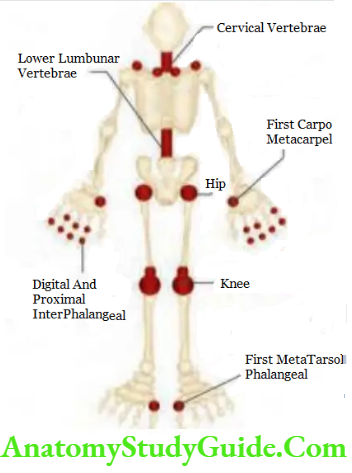

- Joint distribution:

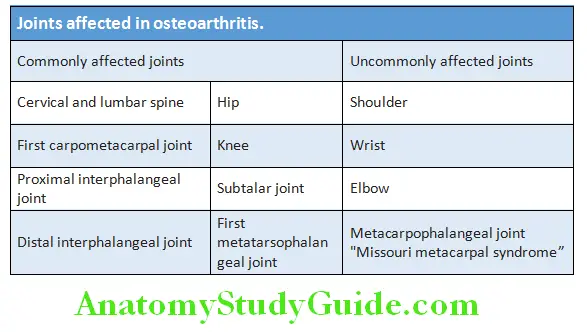

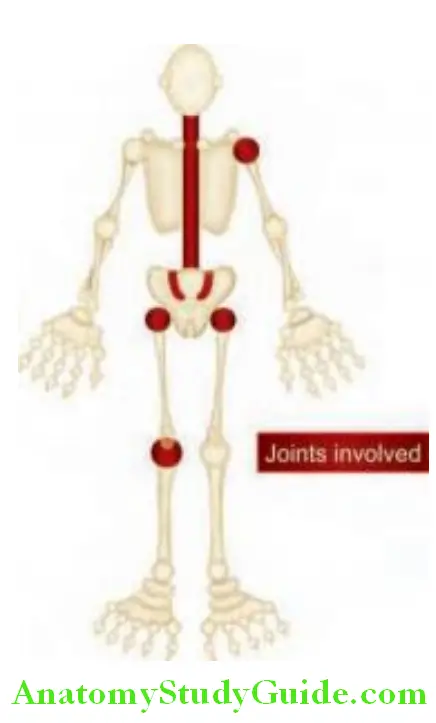

- Crystal and infectios arthritides are often mono or oligoarticular whereas OA and RA are polyarticular.

- Joint involvement in RA tends to be symmetrical and polyarticular whereas spondyloarthropathy, gout and reactive arthritis involvement is asymmetric and oligoarticular.

- Psoriatic arthritis and OA can be either mono or polyarticular and symmetric or asymmetric.

- Upper extremities are commonly affected in RA and OA, whereas lower extremities are affected commonly in reactive arthritis, spondyloarthropathies and gout.

- Axial skeleton is involved in ankylosing spondylitis (Sp A) and OA. Osteoarthritis usually spares wrist, elbow and ankle unless there is a past history of trauma.

- Osteoarthritis involves distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints with sparing of metacarpophalangeal joints. Rheumatoid arthritis spares DIP but affects PIP and metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints.

- Psoriasis and crystal arthropathies affect all three joints.

- Extra-articular manifestations:

- SLE can present with malar rash and oral ulcers.

- Psoriatic skin and nail changes accompany psoriatic arthritis.

- Polymyositis is suggested by proximal muscle weakness.

- Reactive arthritis is suggested by a history of recent gastrointestinal or genitourinary infection, conjunctivitis and oral ulcers.

- Spondyloarthropathies can present with enthesitis or dactylitis causing sausage-shaped digits.

- Disease course:

- Intermittent arthritis is a feature of crystal arthropathies, Lyme arthritis and palindromic rheumatism that may progress to rheumatoid arthritis later.

- Migratory arthritis can be a feature of rheumatic fever, bacterial endocarditis, gonococcal infection and viral fever.

- Patient demographics:

- Incidence of RA, SLE, fibromyalgia are more among premenopausal women compared to men of same age group.

- Spondyloarthropathies occur equally in males and females.

- Gout usually occurs 20 years after puberty in men and 20 years after menopause in women. Rare among premenopausal women unless associated with renal failure.

- RA, SLE, reactive arthritis and sponyloarthropathies occur more among younger individuals whereas OA, polymyalgia rheumatic and giant cell arthritis occur more among elderly.

- Family history is important in spondyloarthropathies, rheumatoid arthritis and Heberden’s nodes of osteoarthritis.

Discusses the classification of arthritis with examples:

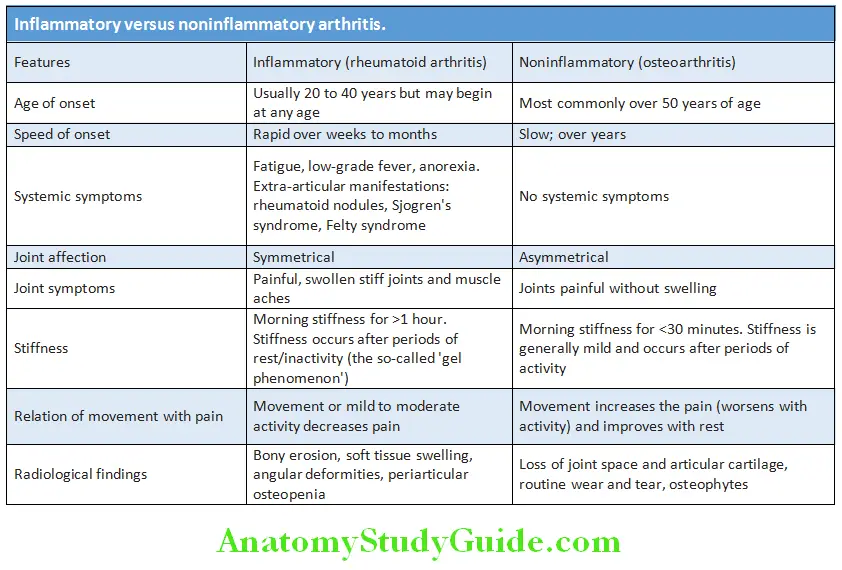

Differences between inflammatory versus noninflammatory arthritis is presented in Table:

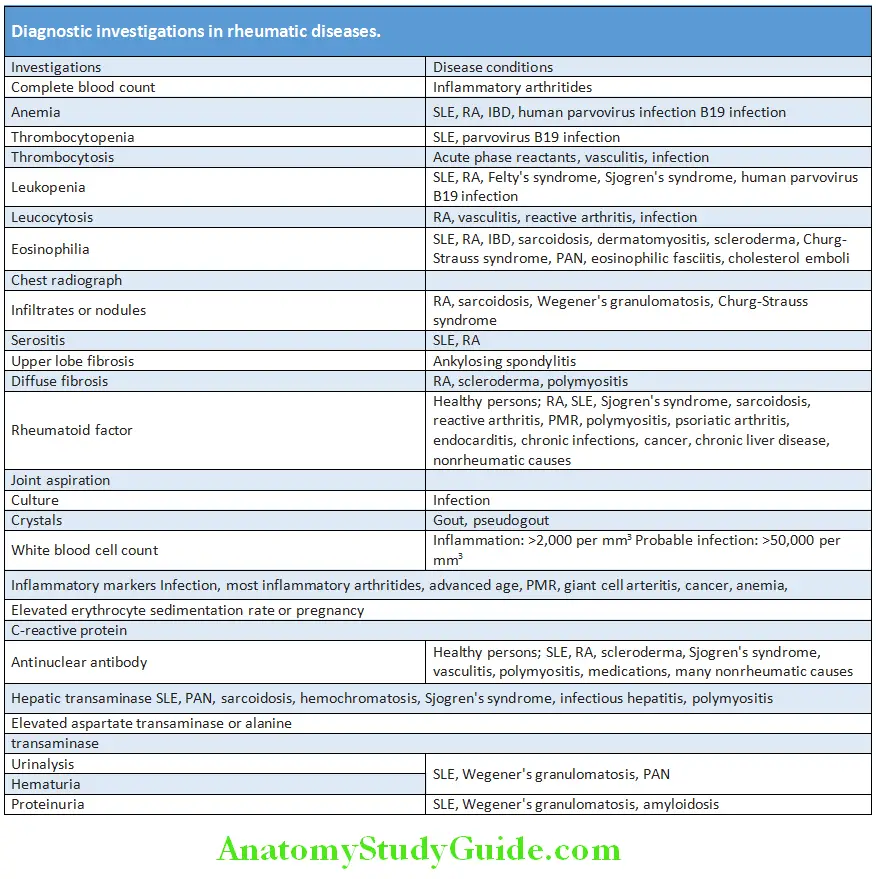

Question 3. Describe the appropriate diagnostic work up based on the etiology.

Answer:

Rheumatological diagnostic tests should be interpreted in the appropriate clinical contex.

- A complete blood count, urine analysis, renal and liver functions test may provide dignostic clues.

- ANA can be positive in 5–10% of general population and may increase with age. Due to the high sensitivity a negative result rules out systemic lupus erythematosus but due to lack of specificity, positive result should be analyzed with caution.

- HLA-B27 positivity with a positive family history is highly suggestive of ankylosing spondylitis. However, relying only on HLA-B27 reports may lead to overdiagnosis as it can be seen in 8% of caucasians.

- Rheumatoid factor lacks sensitivity and specificity; hence both positive and negative results should be interpreted cautiously. Not useful if the patient lacks other criteria for diagnosis.

- Synovial fluid analysis helpful in diagnosing septic and crystal induced arthritis.

- Dignostic imaging is helpful in rheumatological disorders.

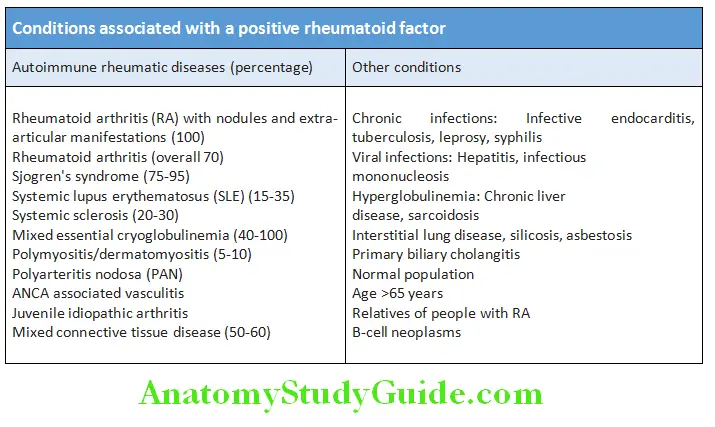

Rheumatoid Factor (RF):

Question 4. Write short note on rheumatoid factor and mention its significance.

Answer:

Rheumatoid factor is an autoantibody (IgM, IgG and IgA) directed against the Fc fragment of human immunoglobulin G (IgG).

Signifiance:

- RF has poor specificity and is positive in 70 to 80% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). It is appropriate and helpful only in patients suspected of having RA. It is not helpful in cases of low clinical suspicion.

- High RF titers are observed with more severe disease and extra-articular disease. The titers generally correlate with severity of disease. However, RF titers are not useful in assessing disease progression.

- It can also be positive in many other conditions.

- 10–30% of patients with long-standing RA are seronegative.

Anticyclic Citrullinated Peptide:

Antibodies (Anti-CCPs, ACPA):

Question 5. Enumerate the significance and indications for anticitrullinated peptide antibody (Anti-CCP).

Answer:

Citrullinated Peptide Antigens:

- These include fibrinogen, type II collagen, alpha enolase and vimentin.

- CCPs are derived from proteins in which arginine residues are converted to citrulline residues by an enzyme peptidyl arginine (which is abundant in inflamed synovium and in a variety of mucosal structures) during a variety of biological processes.

Anticyclic Citrullinated Peptide Antibodies (ACPA):

- These antibodies are useful for diagnosis of RF and may be involved in tissue injury. Many patients (about 70%) of RF have antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides (CCPs).

- These antibodies have much high specificity (93–98%) but less sensitive (60%) for diagnosis of RA.

- Anti-CCPs may be detected even in asymptomatic patients several years before the development of RA and are associated with severe disease. Thus, anti-CCP positive patients may require an aggressive treatment.

- Antibodies against CCPs (anti-CCPs) from immune complexes and deposit in various tissues mainly being the joints.

- Positive results can occur in several autoimmune rheumatic diseases (SLE, Sjogren), tuberculosis, hepatis C infection, and chronic lung diseases.

- Antibodies to mutated citrullinated vimentin (anti-MCV) is associated with more severe disease than anti-CCP antibodies.

- Serum 14-3-3e, which is an intracellular chaperonin protein, has been used diagnostically in RA.

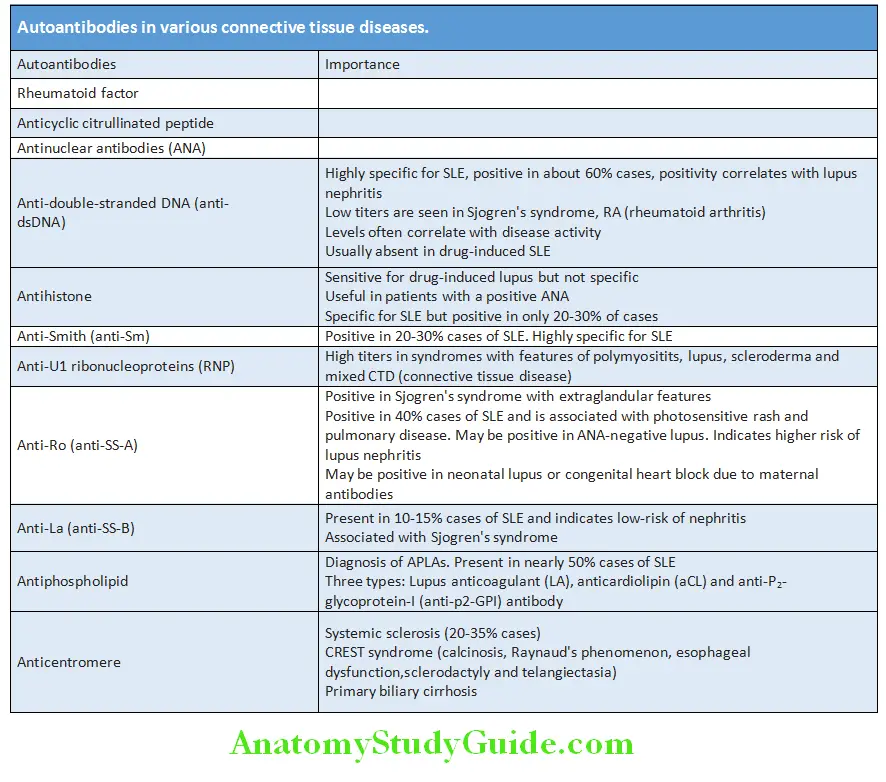

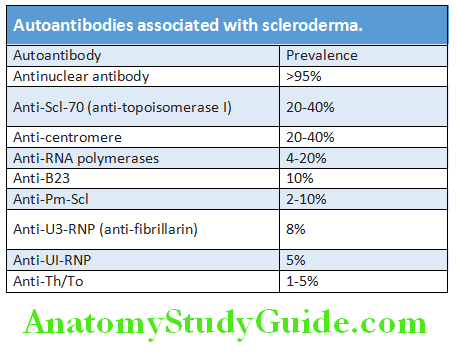

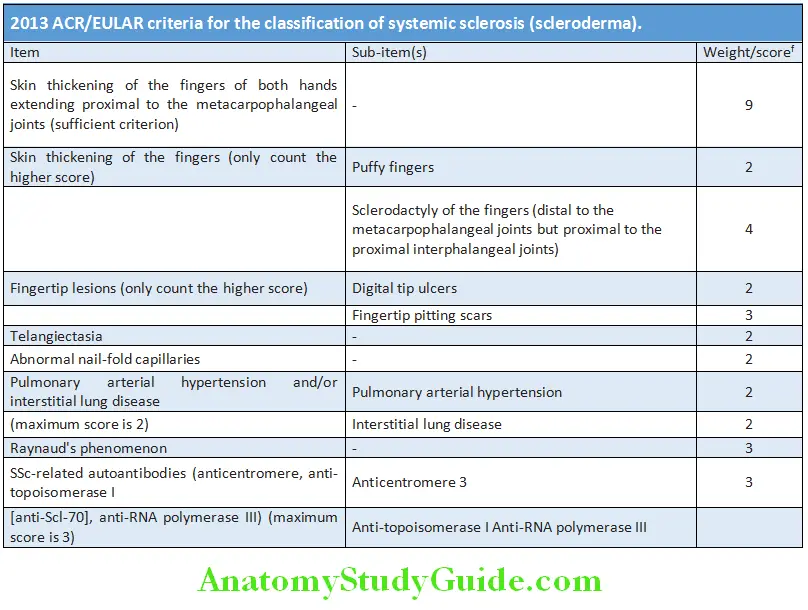

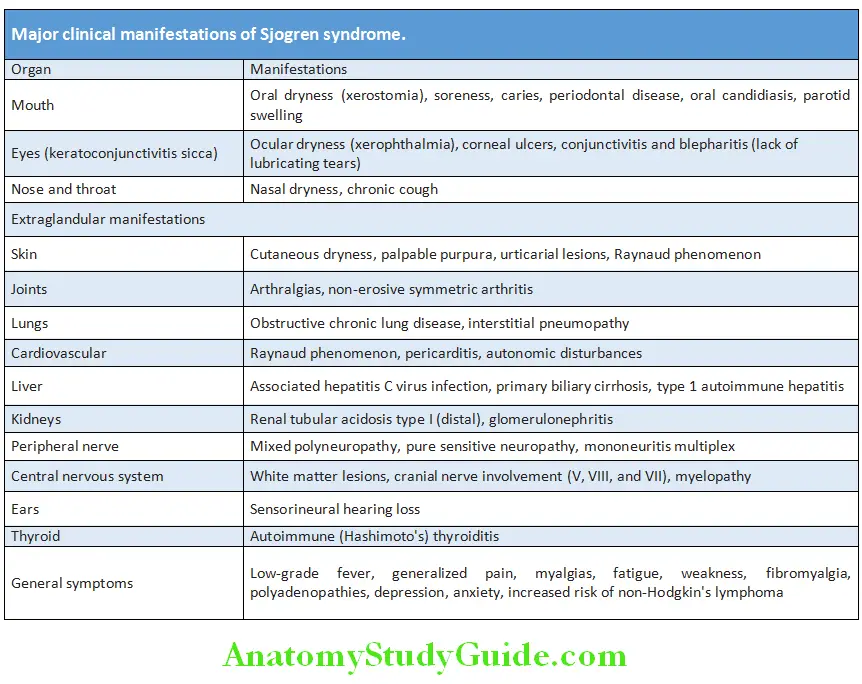

Autoantibodies in Various Connective Tissue Diseases:

Question 6. Enlist the various antibodies seen in patients with connective tissue diseases and mention its significance.

Answer:

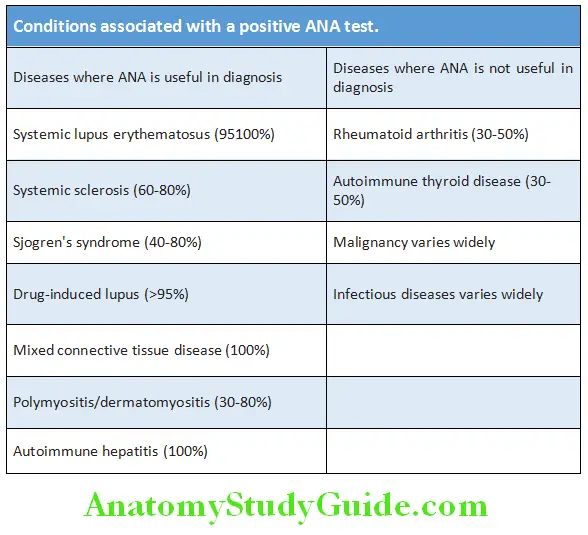

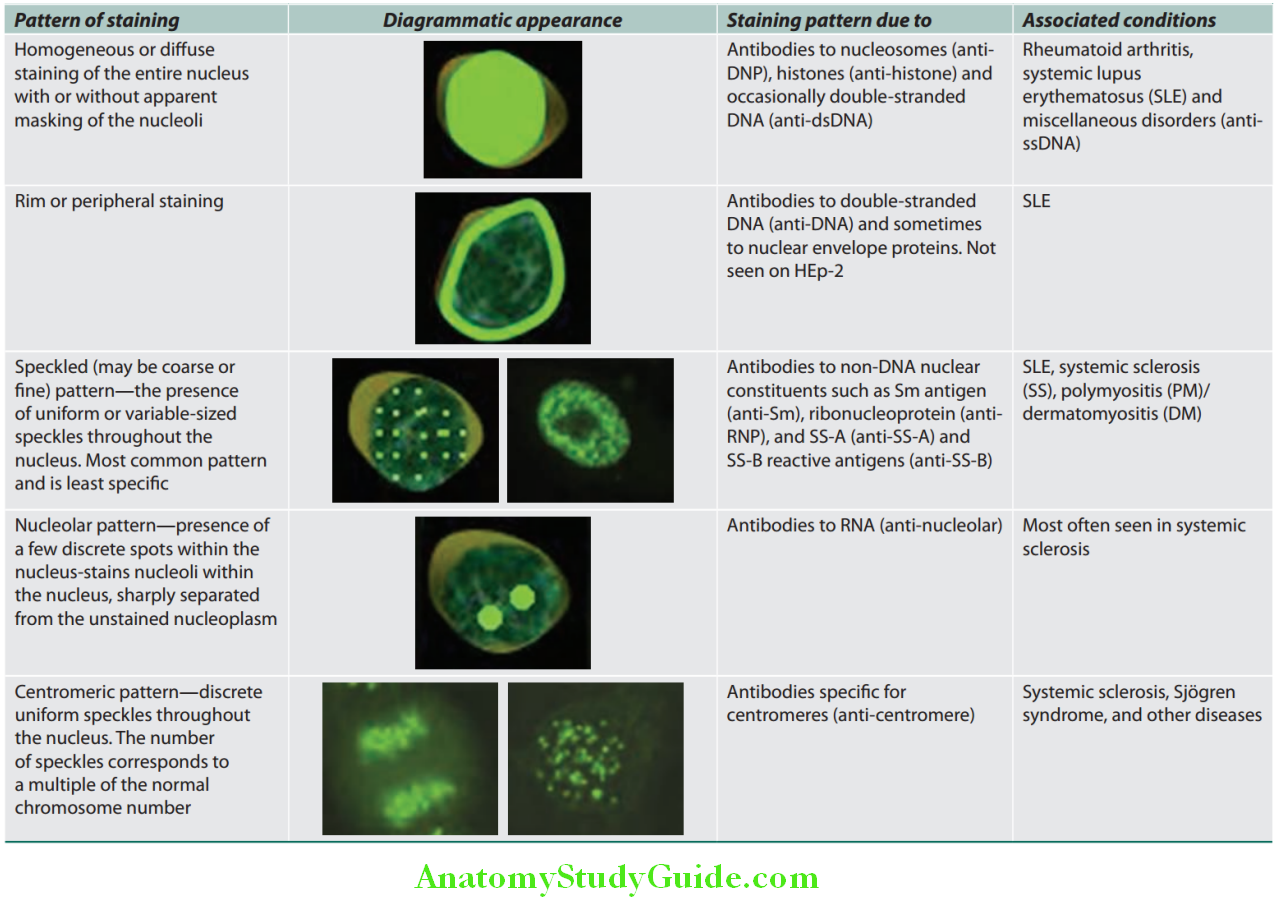

Antinuclear Antibodies:

Question 7. Enumerate the indications, significance and staining patterns of antinuclear antibodies.

Answer:

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are directed against one or more components of the cell nucleus. The component of the nucleus includes DNA, RNA, proteins as well as complexes of proteins with nucleic acid.

Significance:

- High titers of ANA (>1:160) are ofmore diagnostic significance than low titers.

- Circulating levels of ANA do not correlate with severity or activity of the disease.

- ANA is positive in several conditions.

- ANA is used as a screening test for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and systemic sclerosis (SSc). ANA has high sensitivity for SLE (100%) but low specificity (10–40%). A negative ANA almost rules out SLE but a positive result does not confirm it. It should not be used to monitor the course of SLE or other diseases.

Read And Learn More: General Medicine Question And Answers

Tests for detection: ANAs are detected by indirect immunofluorescent staining of fresh-frozen sections of rat liver or kidney or Hep-2 cell lines (a line of human epithelial cells).

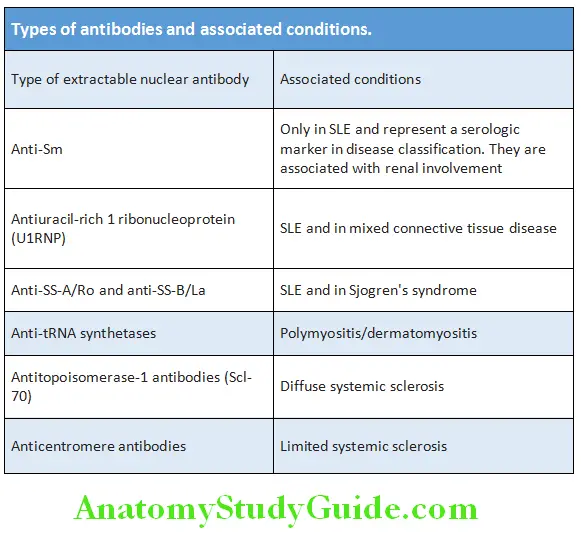

Extractable Nuclear Antibodies:

Question 8. Write short essay/note on extractable nuclear antibodies.

Answer:

These are antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens (ENA) and are directed against small ribonuclear proteins (RNA).

Their sensitivity and specificity are poor. Though used for diagnostic confirmation, they do not exclude a specific CTD.

They do not correlate with disease activity and may be found in patients without active disease

Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies:

Question 9. Write short essay/note on antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), their significance/ANCA associated disorders.

Answer:

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) are heterogeneous group of IgG autoantibodies directed against certain proteins (mainly enzymes) in the cytoplasmic granules of neutrophils and lysosomes of monocytes.

Patterns: On the basis of the target antigens and pattern of immunofluorescence staining, two common patterns of ANCA Have been distinguished.

- Anti-proteinase-3 (PR3-ANCA): It is also called cytoplasmic or cANCA. PR3 is a constituent of neutrophil azurophilic granule. It shares homology with many microbial peptides and antibodies against microbial peptides. Antibodies against proteinase-3 (PR3) form PR3-ANCAs. They produce cytoplasmic fluorescence (cANCA). They are associated with Wegener’s granulomatosis.

- Anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO-ANCA): It is also called perinuclear or pANCA. MPO is a lysosomal enzyme normally involved in producing oxygen-free radicals. Antibodies to myeloperoxidase (MPO) forms MPO-ANCAs which produces perinuclear fluorescence (pANCA). It can be induced by drugs (e.g. propylthiouracil). They are associated with microscopic polyangiitis and Churg-Strauss syndrome.

Signifiance:

- ANCA are strongly associated with small-vessel vasculitis and are useful in the diagnosis and monitoring of systemic vasculitis. For their significance in vasculitis, ANCA should be assayed both with indirect immunofluroscence (screening test) and direct ELISA for proteinase-3 or myeloperoxidase.

- ANCA are not specific for vasculitis. They may be positive in autoimmune liver disease, malignancy, infection [bacterial and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)], inflammatory bowel disease, chronic hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, Felty’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, SLE and pulmonary fibrosis.

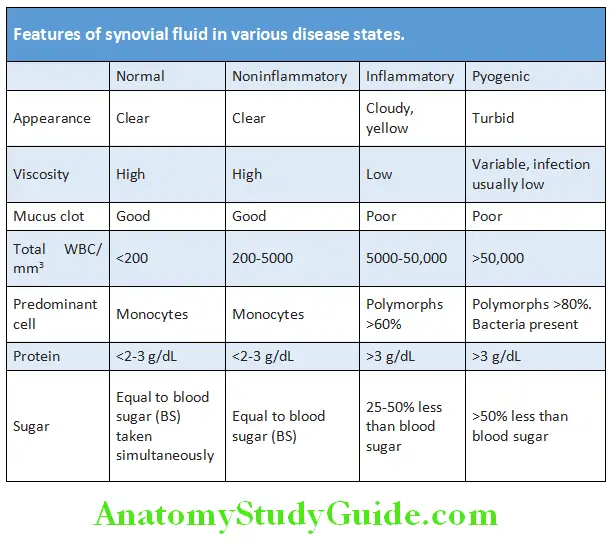

Synovial Fluid in Disease States:

Question 10. Differentiate the synovial fluid features in various arthritis.

(OR)

Enumerate the indications for arthrocentesis.

Answer:

- Arthrocentesis helps in the diagnosis of septic/ infective arthritis and crystal arthropathies and the indications are as below.

- Monoarthritis (acute or chronic)

- Monoarthritis in a patient with chronic polyarthritis

- Suspicion of joint infection

- Crystal-induced arthritis

- Hemarthrosis or trauma with joint effusion.

- Hemorrrhagic effusion may suggest trauma or mechanical derangement, coagulopathy or others.

- Counts less than 2,000 per mm3 may suggest noninflammatory causes like osteoarthritis or trauma.

- WBC count of at least 2,000 per mm3 in synovial fluid suggests inflammation, whereas a count higher than 50,000 per mm3 indicates infection. In later cases, synovial fluid needs to be cultured for ruling out infection.

- Crystal identification by polarized microscopy useful for diagnosis of gout and pseudogout.

Question 11. Describe the role of diagnostic imaging in rheumatological disorders.

Answer:

Currently available modalities include conventional radiography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), arthrography, nuclear medicine scans (bone scintigraphy), and ultrasound.

- Conventional radiography:

- Presence of sacroiliitis indicates ankylosing spondylitis.

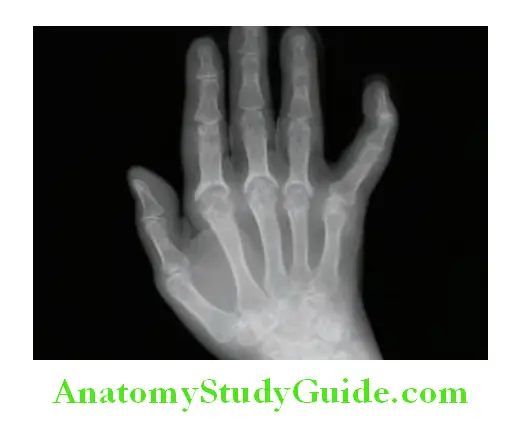

- Periarticular osteopenia with erosions, narrowing of the joint space and juxta-articular osteoporosis suggestive of rheumatoid arthritis.

- “Pencil-in-cup” deformities are suggestive of psoriatic arthritis.

- Chest radiographs may reveal underlying systemic disease. Radiographs showing infiltrates or nodules are suggestive of rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis or microscopic polyangitis. Serositis on radiograph suggests RA or SLE. Ankylosing spondylitis may present with upper lobe fibrosis whereas RA, scleroderma and polymyositis may present with diffuse fibrosis.

- Magnetic resonance imaging is sensitive for diagnosing soft Tissue injuries. MRI done in the early course of RA may reveal cartilage destruction that may not be picked up in routine radiographs. MRI can also be used to demonstrate tophi, synovial changes and erosions.

- Ultrasound is useful in the detection of soft tissue abnormalities such as tendinitis, tenosynovitis, bursitis, enthesitis and entrapment neuropathies.

- CT is useful in the diagnosis of low back pain syndromes. Also HRCT lung can help diagnosis of ILD.

- Nuclear medicine scans have great sensitivity for detecting many disease processes because they image and quantify physiologic biochemical processes, as well as provide anatomic information. The combination with single photon emission computer tomography (SPECT) increases anatomical resolution. Whole-body bone scintigraphy might also help differentiate inflammatory spondyloarthropathies from other inflammatory disorders such as SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis).

Rheumatoid Arthritis:

Question 12. Discuss the etiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, investigations, complication, and management of rheumatoid arthritis.

Answer:

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common form of chronic inflammatory, potentially crippling arthritis with multisystem involvement affecting approximately 1% of the adult population.

Etiology:

The cause is multifactorial and genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors play a part in the pathogenesis of RA.

- Genetic factors: Genetic susceptibility is a major factor in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis.

- HLA genes: RA is linked to specific HLA-DRB1 locus.

- Non-HLA genes: Polymorphism in PTPN22 gene, which encodes a tyrosine phosphatase.

- Abnormal DNA methylation, histone modifications, and microRNA regulation play a key role.

- Environmental arthritogenic agents: They are thought to initiate the disease process. Smoking and several microbial agents (e.g. virus, mycobacteria porphyromonas gingivalis, and Mycoplasma) have been suggested but not proved.

- Autoimmunity: The initial inflammatory synovitis, an autoimmune reaction with T cells is responsible for the chronic destructive nature of rheumatoid arthritis.

Pathogenesis:

The rheumatoid synovium (Pannus) behaves like a locally-invasive tumor. A cascade network of cytokines like granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interleukin (IL)-2, IL-15, IL-13, IL-17, IL-18, interferon-gamma (IFNgamma), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) are involved in the disease progression. B cells, CD4+ T cells, compliment mediated immune activation play a contributory role.

Clinical Features:

Question 13. Enumerate the clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis.

Answer:

- Gender: Female to male ratio is 3:1.

- Age: Most common age of onset is between 30 and 50 years, but the disease can occur at any age. In women in late childbearing years and in men during sixth to eighth decade.

Onset:

The presenting symptoms result from inflammation of the joints, tendons, and bursae. The onset varies:

- Slow and insidious in onset: Presents with malaise, fatigue, anorexia, weakness and generalized musculoskeletal pain.

- Acute onset: Sometimes RA may be very acute in onset, with morning stiffness, polyarthritis and pitting edema. This type occurs more commonly in old age.

- Palindromic onset: Occasionally, patient present with relapsing and remitting episodes of pain, stiffness and swelling that last for only a few hours or days alternating with symptom-free periods.

- Systemic onset/extra-articular involvement: Nonarticular symptoms, which will antedate the onset of arthritis

- Rarely, onset may be monoarticular.

Articular Manifestations:

Question 14. Describe the articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis.

Answer:

- Joints involved: RA can affect any of the synovial (diarthrodial) joints and involvement is usually in a symmetric distribution. Most commonly, RA starts in the small joints, namely metacarpophalangeal (MCP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP), and metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints, followed by the involvement of large joints (wrists, knees, elbows, ankles, hips, and shoulders). Pitting edema over the dorsum gives rise to the “boxing glove” appearance. In RA, the hypertrophied synovium (also called pannus) invades and erodes contiguous cartilage, ligaments and bone.

- Symptoms: These include pain, swelling, and stiffness. Stiffness dominating in the mornings (‘morning stiffness’) lasting more than 1 hour is characteristic. Routine activities early in the morning like brushing teeth and combing hair may be very difficult.

Question 15. Write short note on rheumatoid hand.

Answer:

Hand and wrist: Hands are a major site of involvement and produces significant disability.

- The DIP joint is characteristically always spared unless the patient also has osteoarthritis (both coexist, particularly in elderly patients).

- Spindling of the fingers: It is the earliest finding characterized by swelling of the proximal, but not the distal interphalangeal joints.

- Deformities: Destruction of the joints and soft tissues may lead to chronic, irreversible deformities.

- Ulnar deviation: It results from subluxation of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, with subluxation of the proximal phalanx to the volar side of the hand.

- ‘Swan-neck’ deformity: It is due to hyperextension of the proximal interphalangeal joints (PIP) with flexion of the distal interphalangeal joints (DIP). At DIP joint there is elongation or rupture of attachment of the extensor tendon to the base of the distal phalanx; this results in mallet deformity of distal joint and in addition, an extensor tendon imbalance, leading to hyperextension deformity at PIP joint.

- ‘Boutonniere’ or ‘button-hole’ deformity: This deformity is due to flexion of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints and extension of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. Disruption of the central slip of the extensor tendon and the triangular ligament allows each of the conjoint lateral bands of the digit to slide volarly resulting in a pathologic flexion force and an extension lag; all tendons traversing the PIP joint in this setting elicit flexion of the joint.

- ‘Gamekeepers thumb’: It is the result of hyperextension of the first interphalangeal joint and flexion of the first metacarpophalangeal joint. This leads to loss of thumb mobility and occurrence of pinch.

- Hitchhiker’s thumb (Z-shaped deformity) in which the thumb flexes at the metacarpophalangeal joint and hyperextends at the interphalangeal joint.

- Inflammation of the carpometacarpal joint leads to volar subluxation during contracture of the adductor hallucis.

- ‘Z’ deformity: It is due to radial deviation of the wrist, ulnar deviation of the digits with palmar subluxation of the first MCP joint with hyperextension of the first interphalangeal (IP) joint.

- Carpal tunnel syndrome: Due to synovial proliferation in and around the wrists producing compression of the median nerve.

- The “bow string” sign (prominence of the tendons in the extensor compartment of the hand).

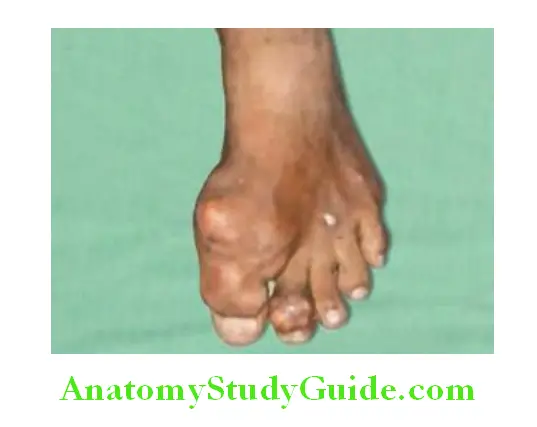

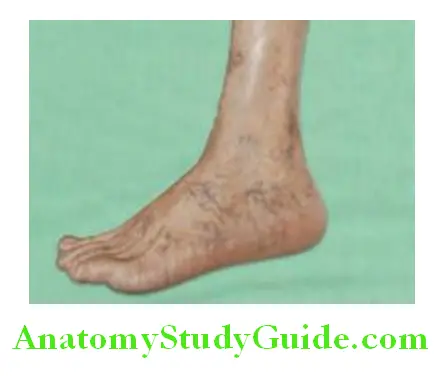

Feet and ankle: In most patients, feet (particularly the MTP joints) are involved early:

- ‘Broadening’ of the forefoot: Due to swelling of the metatarsophalangeal joints.

- Subluxation of the toes at the MTP joints (“cock-up” deformities): Leads to skin ulceration on the top of the toes and painful ambulation because of loss of the cushioning pads which protect the metatarsals heads.

- Hallux valgus deformity and hammer toes.

Larger joints:

- Involvement of large joints (knees, ankles, elbows, hips and shoulders) is common but generally occurs somewhat later than small joint involvement.

- Shoulder joint involvement may present as glenohumeral arthritis, rotator cuff fraying and rupture.

- Synovial cysts: They present as fluctuant masses around involved joints (large or small). Best examples of synovial cyst is popliteal (‘Baker’s) cysts which develops in the knee joint. The knee synovitis produces excess synovial fluid that communicates posteriorly with the cyst (between the knee joint and the popliteal space) but is prevented from returning to the joint by a one-way valve-like mechanism. Ruptured Baker’s cysts can resemble a deep vein thrombosis.

Other joints:

- Axial skeleton: Although most of the spine is spared in RA, the cervical spine (atlantoaxial subluxation) can be involved producing quadriparesis.

- Cricoarytenoid joint involvement may present (30%) with hoarseness of voice and inspiratory stridor.

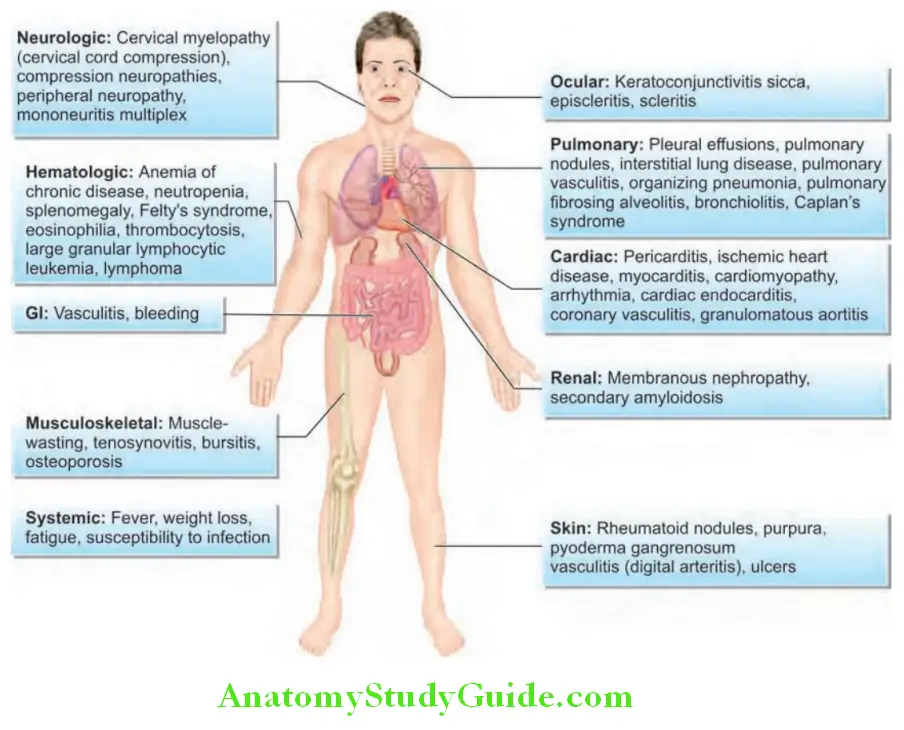

Extra-articular Manifestations:

Question 16. Describe the various systemic manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis.

Answer:

- Constitutional: RA is a systemic disease and features such as fatigue, weight loss, and low-grade fever (<38°C) occur frequently. Systemic features are more common in patients who have RF or ACPA antibodies, or both.

- Rheumatoid nodules:

- Rheumatoid nodules are usually subcutaneous and are typically benign.

- Significance: Nodules are seen in about one-fourth of patients with RA and, almost exclusively in those patients who are seropositive for rheumatoid factor. They are clinical predictors of more severe arthritis, sero-positivity, joint erosions and rheumatoid vasculitis.

- Sites: Typically occur on extensor surfaces, over joints or on areas subject to repeated trauma (particularly forearms sacral prominences, scalp and the Achilles tendon). Rarely, they develop in lungs, pleura, heart, pericardium or in the sclera of the eye.

- Characteristics: On examination, rheumatoid nodules are 2 mm to 5 cm in size, firm and nontender (unless traumatized). They have a characteristic histologic picture (central area of fibrinoid material surrounded by a palisade of proliferating mononuclear cells), and are thought to be triggered by small vessel vasculitis.

- Methotrexate therapy can trigger a syndrome of increased nodulosis despite good control of the joint disease of RA.

- Rheumatoid vasculitis:

- RA-associated small vessel vasculitis: It can manifest as digital infarcts, cutaneous ulcerations, palpable purpurae, distal gangrene and leukocytoclastic vasculitis. They require prompt more aggressive treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

- Other manifestations: Polyneuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex and visceral infarction (resulting in stroke and acute myocardial infarction) and mesenteric arteritis. Pyoderma gangrenosum occurs with increased frequency with RA.

- Dermatological manifestations:

- Rhematoid nodules

- Skin ulcers

- Neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), pyoderma gangerenosum;

- Skin atrophy, petechiae, Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Pleuropulmonary Manifestations:

Question 17. Enlist the pleuropulmonary manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis.

Answer:

- Pleural lesions: Pleural effusions (exudative) occur more commonly in men and are usually small and asymptomatic.

- Pleural fluid is characterized by low glucose and pH.

- Pulmonary lesions:

- Rheumatoid nodules especially in men; usually solid, but may calcify, cavitate or become infected.

- Diffuse interstitial fibrosis causes dyspnea and may progress to cor pulmonale.

- Bronchiolitis obliterans with or without organizing pneumonia.

- Granulomatous pneumonitis.

- Pulmonary arteritis (vasculitis) may result in infarction.

- Caplan’s syndrome: It is characterized by the coexistence of seropositive RA and rounded fibrotic, peripherally located nodules of 0.5–5 cm diameter in the lung along with coal worker’s pneumoconiosis (CWP)/silicosis.

- Treatment induced: Methotrexate induced lung fibrosis, immunosuppression related infections like TB.

- Cardiac manifestations:

- Pericardial effusions are common. Rarely, long-standing pericardial disease results in a fibrinous pericarditis and constrictive pericarditis.

- Coronary artery disease due to premature atherosclerosis. Rarely, myocarditis, valvular involvement and conduction defects.

- Neurological manifestations:

- Peripheral nerve entrapment syndromes: For example, carpal tunnel syndrome (median nerve at the wrist), and tarsal tunnel syndrome (anterior tibial nerve at the ankle).

- Myelopathy: Due to spinal cord compression produced by acquired atlanto-axial dislocation.

- Mononeuritis multiplex: Due to vasculitis.

- Ophthalmological manifestations:

- Sjögren’s syndrome/Sicca complex: Comprising keratoconjunctivitis sicca, xerostomia and salivary (parotid) gland enlargement.

- Scleritis, episcleritis may progress to perforation of the orbit (scleromalacia perforans).

- Brown’s syndrome: Diplopia due to tendinitis of the superior oblique muscles.

- Osteoporosis: Osteoporosis secondary to rheumatoid involvements is very common especially with corticosteroid therapy and immobilization.

- Hematological manifestations:

- RBC: Normocytic normochromic anemia. Causes of anemia in RA include anemia of chronic disease, anemia due to gastrointestinal bleed secondary to NSAIDs/steroids, methotrexate induced folate deficiency, marrow suppression due to disease/drugs and part of hypersplenism if splenomegaly present.

- WBC: Eosinophilia and mild leukocytosis. Neutropenia in cases of Felty’s syndrome and large granular lymphocyte syndrome. Patients with RA are at an increased risk for infections, and this risk is further increased by some therapies.

- Platelets: Thrombocytosis.

- Felty’s syndrome: It is the triad of RA, splenomegaly, and neutropenia.

- Renal involvement: In the form of glomerulonephropathy, vasculitis, drug toxicities and secondary amyloidosis.

- Malignancies: RA patients have an increased risk of lymphomas.

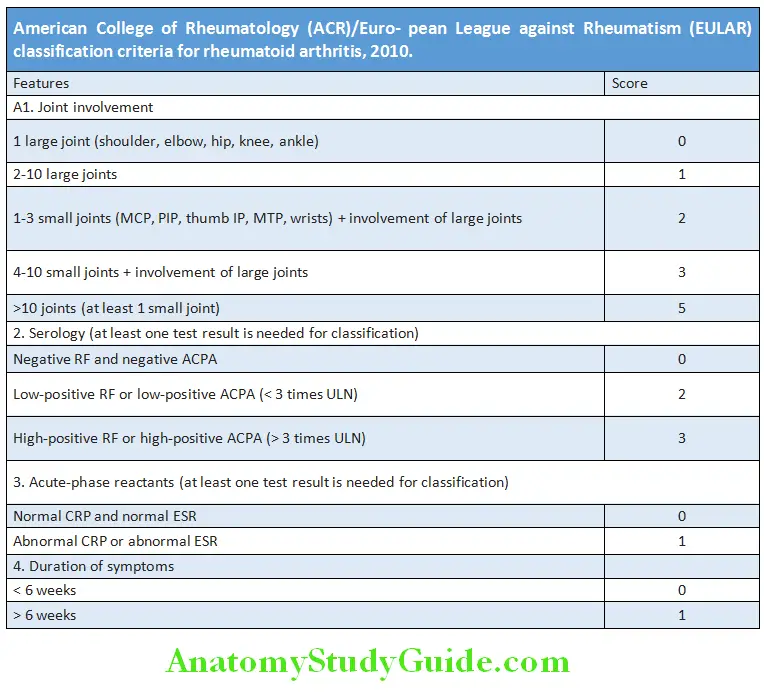

Diagnosis:

Question 18. Enumerate the ACR (American College of Rheumatology)/EULAR criteria for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.

Answer:

- Diagnostic criteria of rheumatoid arthritis: In 2010, a collaborative effort between the American College of Rheumatology and the ACR/European League against Rheumatism presented the criteria for the diagnosis of RA.

- The Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) is used to grade severity of RA.

- Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) are also used in monitoring.

American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for rheumatoid arthritis:

- Morning stiffness*

- Arthritis of 3 joint areas*

- Arthritis of the hands*

- Symmetric arthritis*

- Rheumatoid nodules

- Serum rheumatoid factor positive

- Radiographic changes

These criteria must be present for more than 6 weeks. Presence of 4 criteria favors definite diagnosis of RA.

Investigations:

Question 19. Discuss the diagnostic work up for rheumatoid arthritis.

Answer:

- Serology:

- Rheumatoid factor

- Anticyclic citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA)

- Markers of acute inflammation:

- Anemia of chronic disease is seen in majority of patients, and the degree of anemia is proportional to the activity of the disease.

- Thrombocytosis is common, and platelet counts return to normal as the inflammation is controlled.

- Acute phase reactants, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels parallel the activity of the disease, and their persistent elevation carries poor prognosis (joint destruction and mortality).

- WBC counts may be raised, normal, or profoundly depressed (Felty’s syndrome).

- Other autoantibodies : RA is associated with other autoantibodies, such as antinuclear antibodies (30% of patients) and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies, particularly of the perinuclear type (30% of patients).

- Radiographs of the affected joints: Radiological changes include symmetrical pattern of involvement, juxta-articular osteoporosis, soft tissue swelling, bone erosions and narrowing of the joint space.

- Ultrasonography and MRI: More sensitive than plain radiographs and detects soft-tissue synovitis before joint damage. Doppler ultrasound is useful for demonstration persistent synovitis when deciding on the need for DMARDs or assessing their efficacy.

- Synovial fluid analysis: White blood cell counts typically range from 5000–50,000 per microliter with approximately twothird of the cells being neutrophils with no crystals or organism. None of the synovial fluid findings are pathognomonic.

- Testing for latent tuberculosis: Before starting biological agents.

Question 20. Develop an appropriate treatment plan for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

(or)

Describe the various treatment options for rheumatoid arthritis.

(or)

Describe the basis for biologics and DMARDs in rheumatologic diseases.

(or)

Describe the role and current status of various disease

Answer:

Management:

The early recognition of inflammatory arthritis, before irreversible injury has occurred, is the most important element in the effective management

General Measures:

The goal of therapy is disease remission and to maintain this remission by continuing therapy.

- Rest and splinting of the involved joints during the acute stage.

- Physiotherapy: Helps in mobilization and prevention of contractures.

- Smoking cessation, control of cardiovascular risks, screening for osteoporosis

Medical Therapy:

Three types of medical therapies are used in the treatment of RA:

- NSAIDs

- Glucocorticoids

- DMARDs (both conventional and biologic).

1. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): NSAIDs produce symptomatic reliefbecause of its analgesic and anti- inflammatory properties. However, they do not alter the underlying disease process. Therefore, they are not used without the concomitant use of DMARDs. Their chronic use should be minimized because of its side effects such as gastritis/peptic ulcer disease and impairment of renal function.

2. Glucocorticoids: These are the most potent anti-inflammatory treatments available and cause dramatic and rapid improvement. Not only they produce symptomatic improvement, but also significantly decrease the radiographic progression of RA. However, the longterm therapy is associated with mulltisystem toxicities.

- Prednisolone is the most commonly used glucocorticoid and is administered orally.

- Bridge therapy: In ‘bridge therapy’, glucocorticoids are used first to shut off inflammation rapidly and then to taper them as the DMARD is taking effect.

- Pulse therapy: Remission is induced with IM (intramuscular) depot methylprednisolone 80–120 mg if synovitis persists beyond 6 weeks. Intra-articular long-acting glucocorticoids (e.g. triamcinolone hexacetonide) are used to reduce synovitis.

3. Disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs):

Patients with RA must be started on DMARD therapy as soon as possible. DMARDs have the ability to inhibit greatly the disease process to modify or change the disabling potential of RA. DMARDs are so named because in most of the cases they are able to slow or prevent structural (radiographic) progression of RA.

Conventional DMARDs used in RA:

- Conventional DMARDs exhibit a delayed onset of action and take 2–6 months to exert their full effect.

- Start DMARD therapy early in the disease process. Early in the course of disease, most patients should be started on a combination of DMARDs and analgesics. Before using DMARDs, complete blood count, serum creatinine, aminotransferases, and screening for hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and latent tuberculosis infection. A chest radiograph should be obtained prior to initiating treatment with MTX.

Methotrexate: Currently, methotrexate is the DMARD of choice (considered as ‘gold standard’ drug) for RA and is the anchor drug for most combination therapies.

- Mechanism of action in RA: At the dosages used for RA, methotrexate stimulates extracellular release of adenosine from cells, which has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties. Enzymes inhibited by methotrexate in RA include thymidylate synthetase (TS) and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) transformylase. It should not be prescribed in pregnancy.

- Dose: Usually given orally in the starting dose of 2.5–7.5 mg/week as a single dose. If there is nopositive response within 4–8 weeks, and there is no toxicity, the dose should be increased by 2.5–5 mg/week each month to 15–25 mg/week before considering, the treatment a failure. Oral absorption of methotrexate is variable. If oral treatment is not effective, it is given by subcutaneous injections. It should be monitored with full blood counts and liver biochemistry.

- Folic acid, 1 to 4 mg/day (or 5 mg once a week, on the day following methotrexate dose), reduces most methotrexate associated toxicities (e.g. gastrointestinal intolerance, stomatitis, hepatotoxicity, hyperhomocysteinemia, alopecia) without apparent loss of efficacy. If methotrexate alone does not sufficiently control RA, it is combined with other DMARDs.

Other DMARDs:

- Hydroxychloroquine is used usually in combination with other DMARDs, particularly methotrexate. It is given orally at a dose of 200–400 mg daily. It is the least toxic DMARD but also the least effective as monotherapy. Regular monitoring (every 6 months to a year) by ophthalmoscopy to detect any signs of retinopathy, bull’s eye maculopathy should be done.

- Sulfasalazine: It is effective when given in doses of 1–3 g daily. Monitoring of blood cell counts is recommended, particularly WBC counts, in the first 6 months. Combination of sulfasalazine + hydroxychloroquine + methotrexate is referred to as triple therapy.

- Leflunomide is a pyrimidine antagonist, also inhibits enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, interfering with cell signal transduction. It has a very long half-life and is given daily in a dose of 10–20 mg. The most common toxicity is diarrhea, which may respond to dose reduction. Leflunomide is teratogenic and hepatotoxic. It is used as monotherapy or in combination with methotrexate and other DMARDs.

- Others: These include minocycline, gold salts, penicillamine and cyclosporine are used sparingly now.

Conventional DMARDs used in RA:

- Methotrexate (MTX)

- Hydroxychloroquine

- Sulfasalazine

- Leflunomide

- Azathioprine

- Gold (auranofin)

- Minocycline

- D-penicillamine

Biologic DMARDs/Biologicals:

Question 21. List the biologicals used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Answer:

- They are usually given along with methotrexate or other conventional DMARDs.

- Disadvantages: High cost and long-term toxicities, notably infections (especially cellulitis, septic joints, tuberculosis, histoplas- mosis, coccidioidomycosis, and Listeria) and demyelinating syndromes.

TNF-α Blockers:

- Etanercept, a recombinant TNF receptor fusion protein. Administered subcutaneously in a dose of 25 mg twice weekly.

- Infliximab is a mouse/human chimeric monoclonal antibody against TNF-α. It is given intravenously (3–10 mg/kg) every 4–8 weeks.

- Adalimumab is a recombinant human IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed against TNF-α. It is administered subcutaneously in a dose of 40 mg every other week.

- Newer TNF inhibitors, certolizumab pegol and golimumab, are also effective.

IL-1 Receptor Blocker:

- Anakinra, a recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. It is given subcutaneously in a dose of 100 mg daily.

- Tocilizumab and sarilumab are two newer agents.

Anti-CD20 Antibodies:

- Rituximab is a genetically engineered chimeric murine/human monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 molecule found on the surface of B cells. It is given intravenously as two infusions 2 weeks apart for the treatment of patients with refractory RA.

T-cell Agent:

- Abatacept is a recombinant fusion protein of the extracellular domain of human CTLA4 and a fragment of the Fc domain of human IgGIt is administered by intravenous infusion every 4 weeks in a dose of approximately 10 mg/kg.

JAK inhibitors:

- Tofacitinib, baricitinib, peficitinib, and upadacitinib, can also be used in combination with MTX or as monotherapy.

Immunosuppressants: These are used as third-line drugs for RA that recurs or does not respond to second-line agents. These include

cyclophosphamide and azathioprine. However, in RA with acute vasculitis causing serious organ involvement, intravenous administration

of cyclophosphamide may be lifesaving.

Surgery:

Surgical therapy may improve pain and disability when there is failure of medical therapy. It is useful in maintenance of joint function,

and prevention and correction of deformities. Surgical procedures of the joint include

- Synovectomy of the inflammed joint before joint damage;

- Osteotomy to correct the deformity and relieve pain in the upper end of the tibia, and excision of the lower end of the ulna;

- Arthrodesis of the joint to relieve pain in the atlanto-axial joint, wrists, ankle and subtalar joints;

- Excision arthroplasty

- Joint replacement.

Physiotherapy, Rehabilitation and Assistive Devices:

Exercise and physical activity improve muscle strength. Judicious use of wrist splints can decrease pain.

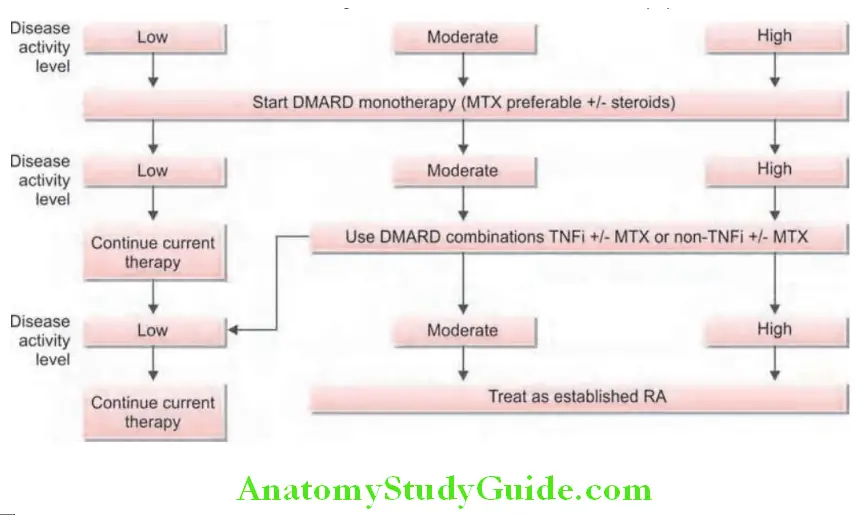

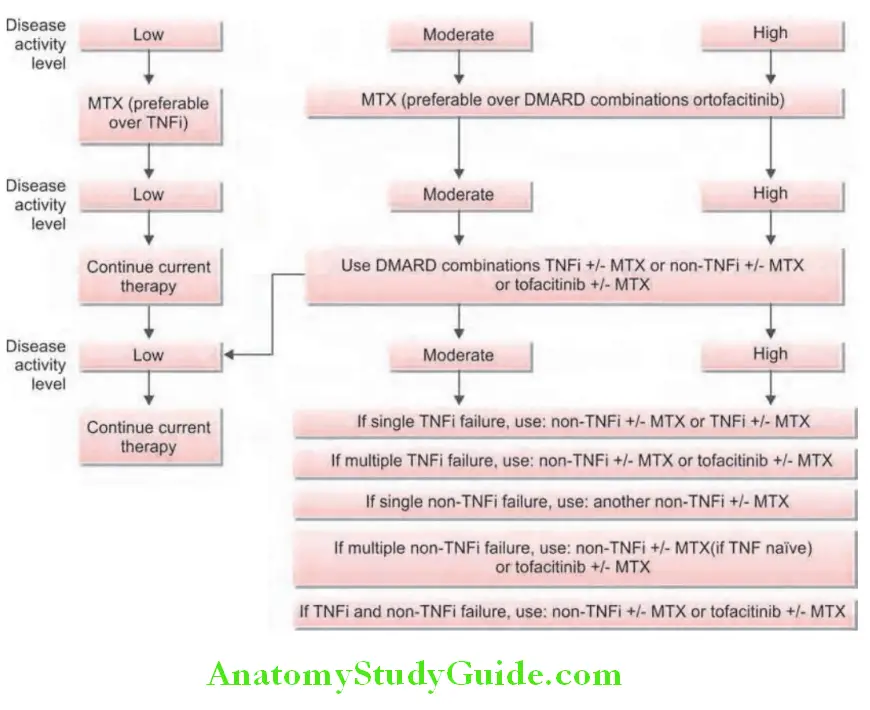

Treatment algorithm for rheumatoid arthritis is presented :

Felty’s Syndrome:

Question 22. Write short essay/note on Felty’s syndrome and its components.

Answer:

- Felty’s syndrome is the triad of RA, neutropenia and splenomegaly.

- It is seen in patients with long-standing chronic, severe and seropositive RA.

- Autoantibodies to deiminated histones (predominantly histone H3) and neutrophil extracellular chromatin traps (NETs) are postulate as the cause.

Clinical Features:

Clinical features of Felty’s syndrome:

- Features of RA (rheumatoid arthritis)

- Splenomegaly

- Lymphadenopathy

- Skin pigmentation

- Fever

- Weight loss

- Rarely recurrent infections and chronic leg ulcers

- Vasculitis

- Subcutaneous nodules

- Portal hypertension

- Higher risk of Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Laboratory Findings:

- Blood: Neutropenia 3 (absolute neutrophil count below 2000/microL), anemia and thrombocytopenia.

- Rheumatoid factor (RF): High titers.

- Circulating immune complexes (CIC): Increased levels.

Treatment:

- Do not require special specific therapy; instead treat underlying severe RA. Immunosuppressive agents particularly methotrexate and azathioprine are beneficial.

- G-CSF and GM-CSF can be tried.

- Splenectomy is indicated in: Severe and persistent neutropenia (< 500 cells/mm 3), recurrent or serious bacterial infections, chronic, nonhealing leg ulcers, hypersplenism producing severe anemia or thrombocytopenic hemorrhage.

Prognosis:

Poor with an increased mortality due to increased incidence of severe infection.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflmmatory Drugs (NSAIDs):

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the most widely used drugs, but they have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Oral NSAIDs are used for the management of pain due to inflammation.

Mechanism of NSAID action: Arachidonic acid (AA) is derived from membrane phospholipid and its metabolism occurs along two major enzymatic pathways namely; cyclooxygenase pathway (produces prostaglandins by the cyclooxygenase) (COX) and lipoxygenase pathway (produces leukotrienes by 5-lipoxygenase).

Question 23. Write briefly on COX enzymes and COX-2 inhibitors.

Answer:

Traditional NSAIDs versus COX-2 Inhibitors:

- Traditional NSAIDs (e.g. ibuprofen, diclofenac, and naproxen) exert their anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting synthesis of prostaglandin from arachidonic acid by blocking both COX enzymes. They do not have a diseasemodifying effect in either osteoarthritis or inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

- Inhibition of COX-1 is required for anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects, but can damage the mucosa of stomach and duodenum and is associated with an increased risk of upper gastrointestinal ulceration, bleeding and perforation. Simultaneous administration of omeprazole (20 mg daily) or misoprostol (200 μg twice or 3 times daily) reduces the risk of NSAID-induced ulceration and bleeding. Other side-effects include fluid retention, renal impairment due to inhibition of renal prostaglandin production, and rashes.

- COX-2 (cyclooxygenase-2) selective NSAIDs (e.g. celecoxib, etoricoxib, etodolac, rofecoxib and valdecoxib) selectively inhibit COX-They have analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties similar to traditional NSAIDs. However, they are much less likely to cause gastrointestinal toxicity and have minimal antiplatelet effects. Similar to traditional NSAIDs, they can produce significant changes in renal function, and hence, should be cautiously used in patients with diabetes, dehydration and congestive heart failure.

- They play an important role in the management of inflammation and pain caused by arthritis. It has been observed that there is a higher risk of myocardial infarction and stroke (thromboembolic complications) in patients using COX-2 inhibitors compared to traditional NSAIDs. Hence, two COX-2 inhibitors namely rofecoxib and valdecoxib have been withdrawn. NSAIDs like diclofenac, nabumetone, meloxicam, and etodolac, are also relatively selective for COX-2 at lower doses.

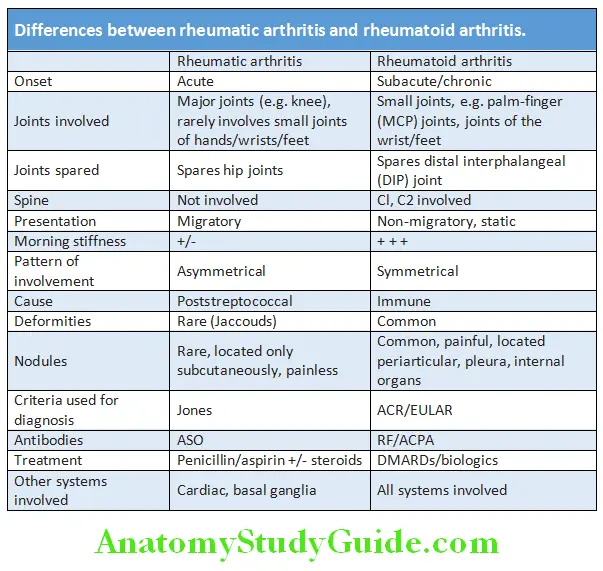

Differences between Rheumatic Arthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis:

Question 24. Differentiate between rheumatic arthritis from rheumatoid arthritis.

Answer:

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus:

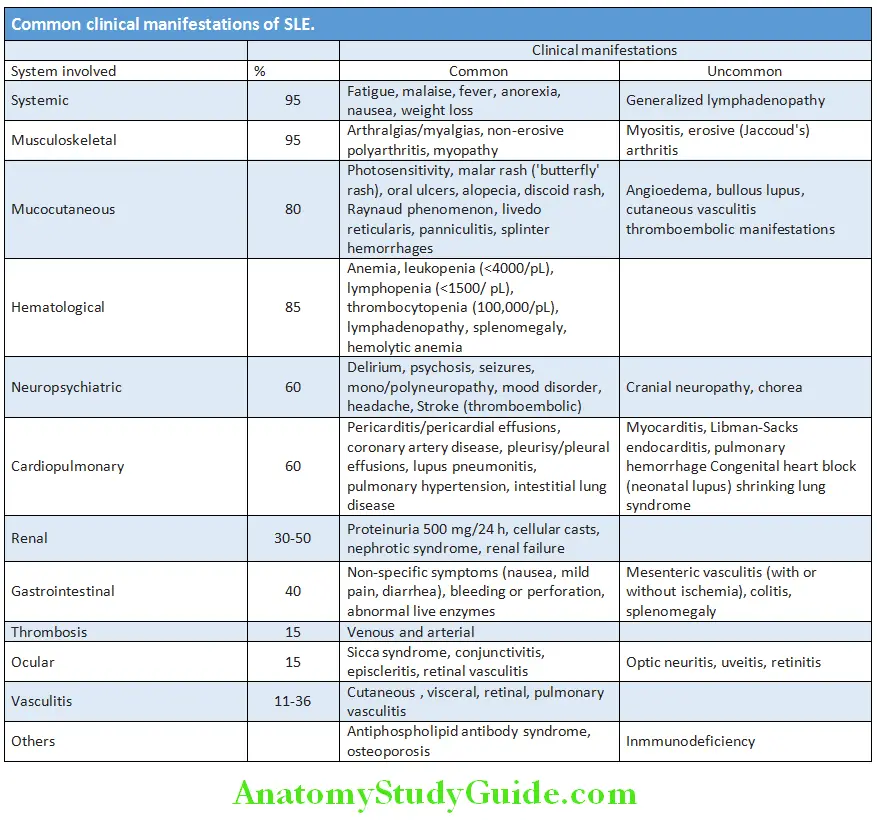

Question 25. Describe the clinical manifestations, diagnosis and management of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Answer:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, multisystemic autoimmune disease that results from immune systemmediated tissue damage and is characterized by the presence of broad spectrum of autoantibodies.

- Arthralgia and rashes are the most common clinical features, whereas cerebral and renal diseases constitute most serious problems.

- Age: It usually occurs in young women between 20 to 30 years, but may manifest at any age.

- Sex: It predominantly affects women, with female-to-male ratio of 9:1.

Clinical Features:

Question 26. Write short essay/note on clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus

Answer:

Musculoskeletal Manifestations:

- Arthralgia and nonerosive arthritis are most common (>85%).

- Commonly involves proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints of the hand, along with the knees and wrists.

- In about 10% of patients, deformities result from damage to periarticular tissue, a condition termed Jaccoud’s arthropathy.

Cutaneous Manifestations:

- Classic malar rash consists of erythematous (flat or raised) facial rash with a butterfly distribution across the malar and nasal prominences and sparing of the nasolabial folds and is seen in 30–60% of patients. Butterfly rash is often triggered by sun exposure.

- Discoid lupus is a benign variant of lupus in which only the skin is involved. Discoid rash consists of erythematous, slightly raised patches with adherent keratotic scaling and follicular plugging. Discoid rash without any systemic features occurs in discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). Only 5% of patients with DLE have SLE; however, as many as 20% SLE patients have DLE. This rash is primarily seen on the face and scalp.

- Generalized photosensitivity (skin rash on exposure to sunlight) and alopecia.

Mucous Membrane Manifestations:

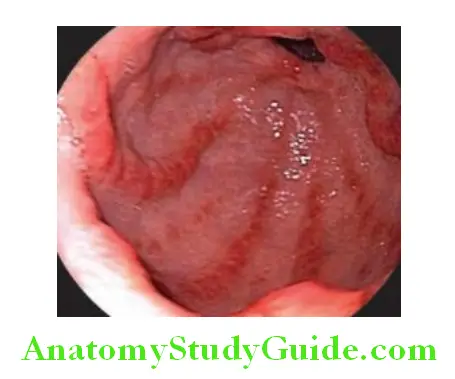

Recurrent crops of small, painful ulcerations on the oral or nasal mucosa. Dryness secondary to Sjögren’s syndrome.

Hematologic Manifestations:

Antibodies that target each of the cellular blood elements are responsible for hematological changes.

- RBC: Normocytic normochromic anemia, reflecting chronic illness. Hemolytic anemia: Coombs’ test positive or microangiopathic hemolysis.

- WBC: Leukopenia, particularly lymphopenia.

- Platelets: Idiopathic/immune thrombocytopenic purpura induced by antiplatelet antibodies.

- Antibodies to clotting factors can contribute to impaired clot formation and hemorrhage.

Renal Manifestations:

Question 27. Enumerate the renal manifestations of SLE.

Answer:

- Kidney may be involved in 30–50% of SLE patients and is one of the most important organs involved.

- Often asymptomatic in most lupus patients, particularly initially. Hence, urinalysis should be done in any person suspected of having SLE followed by regular urinalysis and blood pressure monitoring.

- Characterized by proteinuria (>500 mg/24 hours) and/or cellular (red cell) casts.

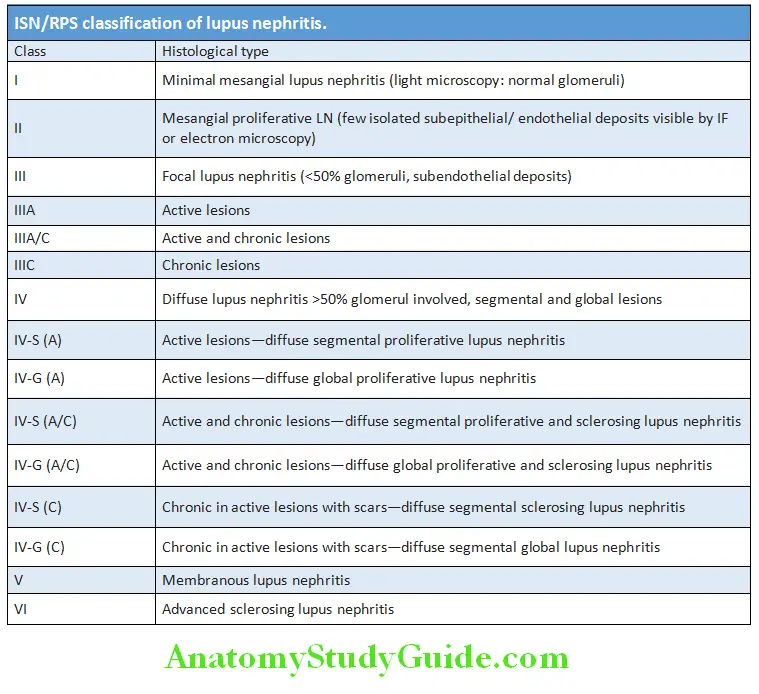

- Histological classification of lupus nephritis.

Neuropsychiatric Features:

- Nervous system involvement in SLE produces both

- neurologic and psychiatric manifestations.

- Clinical features include cognitive dysfunction (due to SLE cerebritis), headache and seizures, psychiatric features including depression and psychosis. Peripheral nervous system involvement can cause neuropathy. Cranial nerve and ocular involvement due to vasculopathy.

Cardiac Manifestations:

- Pericarditis most frequent; serious manifestations are myocarditis and Libman-Sack (noninfective endocarditis involving the mitral valve) endocarditis.

- Increased risk for myocardial infarction, usually due to accelerated atherosclerosis and vasculitis.

Pulmonary Manifestations:

- Pleural lesions: Pleurisy with or without pleural effusion—most common pulmonary manifestation. Pleural effusion is exudative with low C3 and ANA test positive in the pleural fluid.

- Lung lesions: Pneumonitis (exclude infection before ascribing a lung lesion to SLE), shrinking lung syndrome, interstitial inflammation leading to fibrosis and intra-alveolar hemorrhage.

Gastrointestinal Features:

Non-specific diffuse abdominal pain (caused by autoimmune peritonitis and/or intestinal vasculitis), nausea sometimes with vomiting and diarrhea. Increases in serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Mesenteric vasculitis can cause infarction or perforation of small intestine.

Ocular Manifestations:

- Sicca syndrome (Sjogren’s syndrome) and nonspecific conjunctivitis are common.

- Serious manifestations are retinal vasculitis (can cause infarcts and cytoid bodies) and optic neuritis. Complications of glucocorticosteroid therapy include cataracts (common) and glaucoma.

Other Manifestations:

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy), antiphospholipid syndrome, osteoporosis, and complement deficiencies are associated with SLE. Increased risk of hematologic malignancies (particularly non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) and possibly lung and hepatobiliary cancers.

Poor progmnostic factors in SLE include diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis, male sex, older age at presentation, black race, hypertension and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

Clinical features are summarized diagrammatically Causes of death in SLE.

Causes of death in SLE:

- Infections and renal failure: Cause of death in the first decade of disease

- Thromboembolic events: Cause of death in the second and later decades

- Cardiovascular: Due to premature atherosclerosis

Laboratory Findings:

Purpose:

- To establish or rule out the diagnosis

- Follow The Course Of Disease

- To identify adverse effects of therapies.

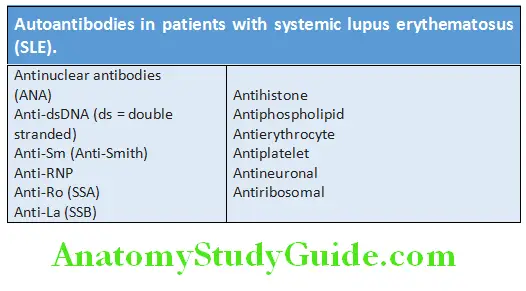

Autoantibodies in SLE:

Question 28. Describe the diagnostic work up and the role of autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Answer:

- SLE is characterized by the production of several diverse autoantibodies. Some antibodies are against different nuclear and cytoplasmic components of the cell that are not organ specific. Other antibodies are directed against specific cell surface antigens of blood cells.

- Importance of autoantibodies:

- Diagnosis and management of patients with SLE

- Responsible for pathogenesis of tissue damage.

Types of Antibodies:

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA): Best screening test and >90% of the patients show a positive test. However, a positive test is not specific for SLE. It can be positive in some normal individual (especially elderly), other autoimmune diseases, acute viral infections, chronic inflammatory processes and with certain drugs.

- Anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibodies are common in SLE. Anti-Sm antibodies are highly specific for SLE. Rising levels of anti-dsDNA and low levels of complement (C3 and C4) usually reflect disease activity.

- Rheumatoid factor is positive in 30%.

Other Tests:

- Complete blood count: Essential and aids in diagnosis and management. Anemia (normocytic normochromic and Coombs’ positive), leucopenia, lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia may be present.

- Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT): Prolonged in the presence of pathogenic antiphospholipid antibodies. These antibodies give a false-positive result in the serologic test for syphilis.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): Nonspecific indicator of systemic inflammation. It is often monitored in many patients to know the disease activity.

- C-reactive protein (CRP): It is an acute phase reactant which is relatively uninformative and normal in SLE. It does not usually rise with disease activity unless there is infection, arthritis or serositis.

- Urinalysis: When there is active nephritis, urinalysis shows proteinuria, hematuria and cellular (red and white blood cell casts in the urinary sediment suggest proliferative glomerulonephritis) or granular casts. Blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine are elevated in acute kidney injury. If there is proteinuria, urine albumin/creatinine ratio should be measured. Renal biopsy confirms renal involvement.

- Complement levels: Low levels of C3 indicate active disease especially nephritis.

- LE cell: Phagocytic leukocyte (neutrophil or macrophage) that has engulfed the denatured nucleus of an injured cell is positive. Rarely done nowadays.

Imaging:

- Chest X-ray: To exclude other pathology, for pulmonary and cardiac pathology.

- High resolution CT: To demonstrate fibrotic lung.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain or spinal cord in cases with central nervous system disease involvement.

- Echocardiography to diagnose pericardial and endocardial involvement.

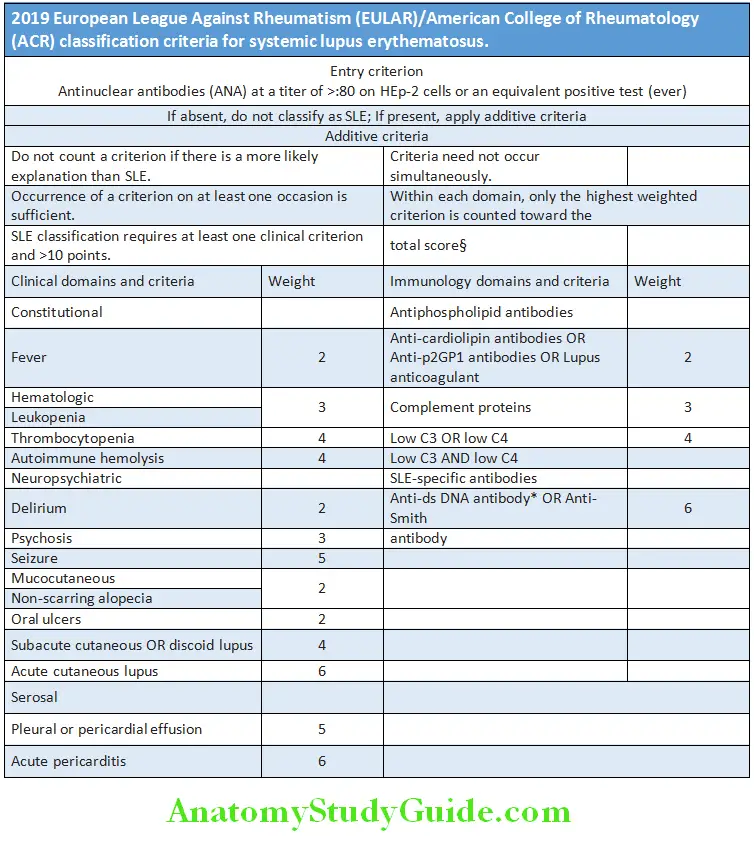

Diagnostic Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus:

Question 29. List the diagnostic criteria/revised American Rheumatism Association criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The clinical presentation of SLE is so variable that the American College of Rheumatology has established a complex set of criteria

Answer:

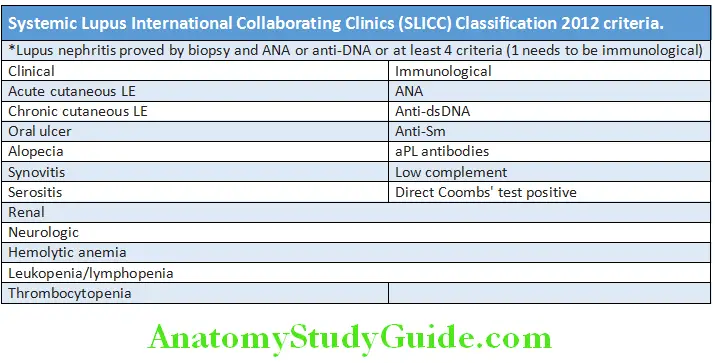

Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) Classification 2012 criteria:

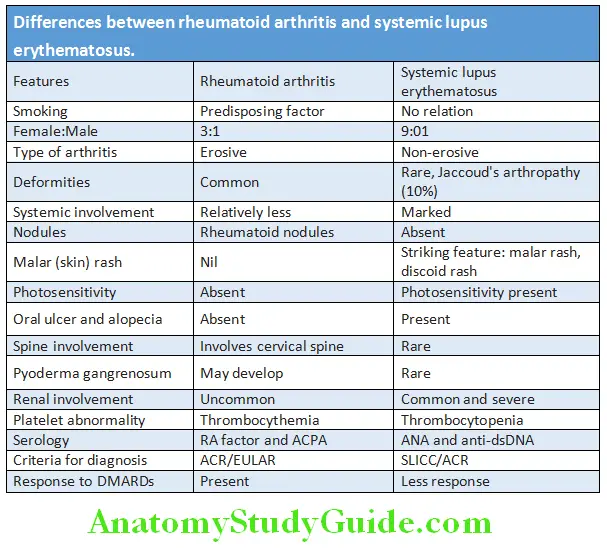

Differences between rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus are presented in Table:

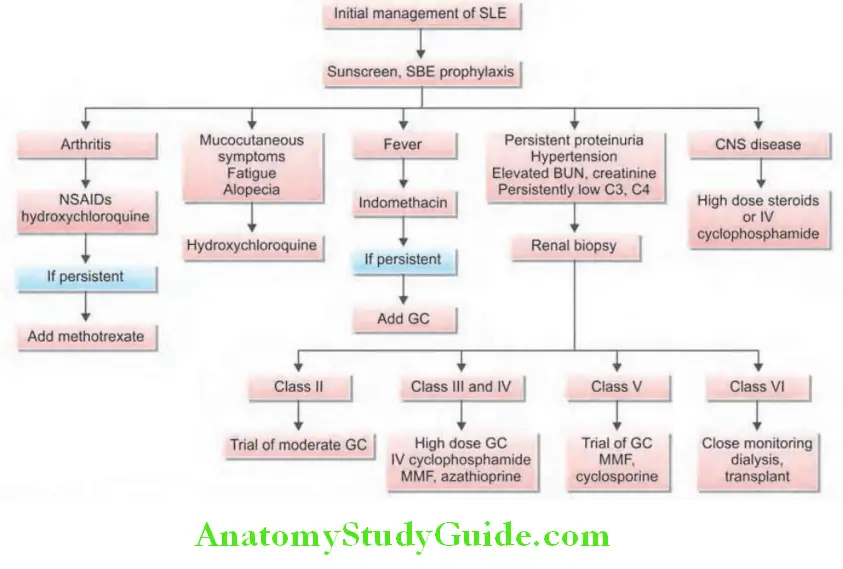

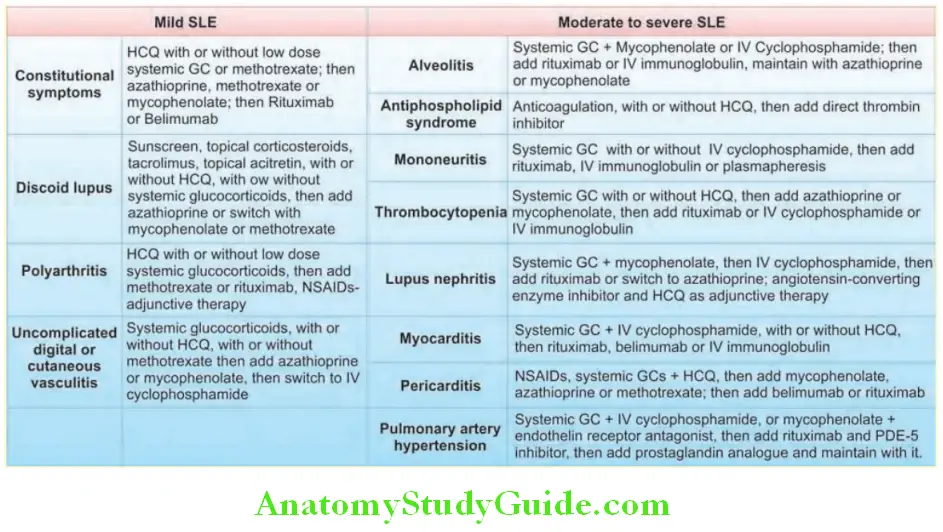

Management:

Question 30. Describe the management principles of systemic lupus erythematosus.

Answer:

General:

- To avoid known triggers of disease exacerbation, such as ultraviolet light, smoking cessation.

- Need for adequate rest.

Conservative therapies for management of non-life-threatening disease:

In patients with fatigue, pain, and autoantibodies of SLE, but without major organ involvement are managed by analgesics (NSAIDs), antimalarials (hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and quinacrine) and low-dose corticosteroids. Skin lesions and arthritis also respond to hydroxychloroquine. Photosensitive skin lesions need application of sun-screen lotions.

Life-threatening SLE Proliferative forms of lupus nephritis:

- Life-threatening SLE or patients with severe symptoms should receive corticosteroids.

- Acutely ill patients and patients with active proliferative glomerulonephritis may be treated with prednisone at 60 mg daily or 1 g of intravenous methylprednisolone administered daily for 3 days.

- Immunosuppressive agents: These include azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, my cophenolate mofetil and are also useful in controlling severe disease. They are particularly useful in patients with renal involvement. A combination of intravenous cyclophosphamide and steroids is the most effective regimen. Following intravenouscyclophosphamide, oral mycophenolate mofetil is an alternative to maintain remission.

- Drugs targeting B-cell pathways, such as belimumab and rituximab are used in refractory cases.

Drug-induced Lupus:

Question 31. Write short essay/note on drug-induced lupus.

Answer:

It is a syndrome consisting of positive ANA associated with symptoms such as fever, malaise, arthritis or intense arthralgias/

myalgias, serositis, and/or rash.

Etiology: The syndrome develops during therapy with certain medications and includes:

- Drugs: Antiarrhythmics (e.g. procainamide, diltiazem, disopyramide, and propafenone), antihypertensive (e.g. hydralazine), methyl dopa, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta blockers, antithyroid propylthiouracil, antipsychotics (e.g. chlorpromazine and lithium), anticonvulsants (e.g. carbamazepine and phenytoin), antibiotics (e.g. isoniazid, minocycline, and macrodantin), antirheumatic (e.g. sulfasalazine), diuretic (e.g. hydrochlorothiazide) and antihyperlipidemics (e.g. lovastatin and simvastatin).

- Biologic agents: Interferons and TNF inhibitors.

Symptoms: Usually resolve after discontinuation of the offending drug.

Features that differentiate drug-induced lupus from SLE.

Drug-induced lupus:

- Less female predilection than SLE

- Kidneys or brain involvement rare, less cutaneous involvement

- Antinuclear antibodies positive; antihistone antibodies

- Positive (95%); autoantibodies to dsDNA absent

- C3 levels normal

Seronegative Arthritis:

Question 32. Differentiate seropositive arthritis from seronegative arthritis.

Answer:

- Arthritis can be divided into seropositive and seronegative.

- Seropositive arthritis refers to the presence of rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP in the blood.

- Seronegative arthritis generally called ‘seronegative spondyloarthropathy’ and include any losing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and reactive arthritis.

Spondyloarthropathies (Spondyloarthritides):

Question 33. Write short essay/note on spondyloarthropathies.

(or)

Write short essay/note on seronegative spondyloarthropathies (SSA).

Answer:

Definition: The spondyloarthropathies (SpAs) are a group of related inflammatory joint diseases that share clinical features and genetic susceptibility.

Diseases included under spondyloarthropathies (SpAs):

- Ankylosing spondylitis (AnS)

- Reactive arthritis (ReA) (including Reiter’s syndrome)

- Psoriatic arthritis (PsA)

- Arthropathy associated with inflammatory bowel disease

- Undifferentiated spondyloarthritis

Common Features of SpAs:

- Common clinical features:

- Strong predilection for the spine, in particular the sacroiliac joints. Inflammatory back pain due to sacroiliitis and spondylitis.

- Tendency for new bone formation at sites of chronic inflammation, with joint ankylosis as a consequence.

- If peripheral arthritis occurs, it is usually in the lower extremity and asymmetrical.

- Predilection for sites of tendon insertion into bone (enthesis). Enthesitis is inflammation at sites where tendons, ligaments or joint capsules attach to bone and is one of the most specific clinical manifestations of the SpAs.

- RF negative; hence, known as ‘seronegative’.

- Common genetic predisposing factor: All subsets have an association with HLA-B27 allele.

Ankylosing Spondylitis:

Question 34. Discuss the clinical features, diagnosis and management ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid spondylitis or BekhterevStrümpell-Marie disease.

Answer:

Ankylosing spondylitis (AnS) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown causes that primarily affects the axial skeleton (predominantly sacroiliac joints and spine). The peripheral joints and extra-articular structures are also frequently involved.

Age and gender: Usually begins in the second or third decade; male to female ratio is between 2:1 and 3:1.

Clinical Features:

Targets in ankylosing spondylitis: Mainly involves spine, sacroiliac joints and large peripheral joints (hip, shoulder) in an asymmetrical pattern.

Involvement of lumbar spine:

- Classical presentation is the insidious onset of inflammatory low back pain. The pain is dull and located in the lower lumbar regions or gluteal region and shows nocturnal exacerbation.

- Back pain persists for >3 months. It is accompanied by early-morning stiffness that typically improves with activity/exercise and exacerbated by inactivity.

- “Inflammatory back pain” typically exhibits at least four of the following five features:

- Age of onset <40 years

- Insidious onset

- Improvement with exercise

- No improvement with rest

- Pain at night

- Physical examination: Physical examination of the spine shows loss of spinal mobility in all directions and pain on sacroiliac stressing.

- Modified Schober test: Used to measure lumbar spine flexion. The patient stands upright with heels together. Two marks are made on the spine; one at the lumbosacral junction (identified by a horizontal line between the posterosuperior iliac spines) and another 10 cm above. The patient then bends forward maximally with knees fully extended. The distance between the two marks is measured. This distance increases by >5 cm in the case of normal mobility and by <4 cm in the case of decreased mobility.

Involvement of sacroiliac joint:

The tests mentioned below produce stress and pain in the sacroiliac joint.

- Patrick’s test: Pain in the sacroiliac joints may be elicited either by direct pressure or by maneuvers that stress the joint, namely, Patrick’s test. One leg is guided into ‘figure of 4’ position with the ipsilateral ankle resting across the contralateral thigh. The ipsilateral knee is then pressed downwards with one hand while providing counter pressure with the other hand on the contralateral anterior superior iliac spine.

- FABER (flexion abduction external rotation) maneuver: Patient lies supine while the examiner flexes and externally rotates the hip.

- Gaenslen’s maneuver: The examiner extends the hip by letting the leg dangle off the side of the examining table.

- Occiput to wall test (Flesch test): Normally zero, in AnS it is increased.

Enthesitis:

- Enthesitis is inflammation at the sites of tendon/ligament insertions.

- Heel pain due to inflammation at the Achilles tendon (Achilles tendinitis) and plantar fascia (plantar fasciitis) at calcaneal insertions is common. Like arthritis, enthesitis is also aggravated by rest and improved with activity.

- Other sites of enthesitis include superior and inferior aspects of patella, metatarsal heads and spinal ligament insertions on vertebral bodies.

Other sites:

- Involvement of the thoracic spine, costovertebral joints and costosternal joints leads to chest pain, reduced expansion of chest (<5 cm) and thoracic kyphosis.

- Involvement of the cervical spine produces neck pain and a forward stoop of the neck.

- Peripheral arthritis usually occurs late and asymmetric.

- Involvement of hips and shoulders result in pain and limitation of movement.

- Dactylitis (sausage digits) is characterized by diffuse swelling of toes or fingers.

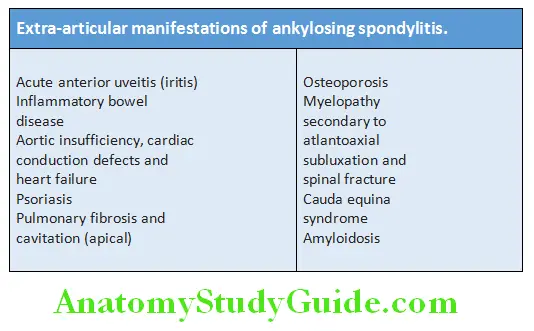

Extra-articular manifestations:

Investigations:

Describe the diagnostic work up and management of ankylosing spondylitis:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein: Raised.

- Tests for rheumatoid factor (RF): Negative.

- Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) and antinuclear antibodies (ANAs): Negative.

- HLA-B27: Present in >90% cases. High sensitivity and specificity.

- MRI and bone scan: They can detect early sacroiliitis.

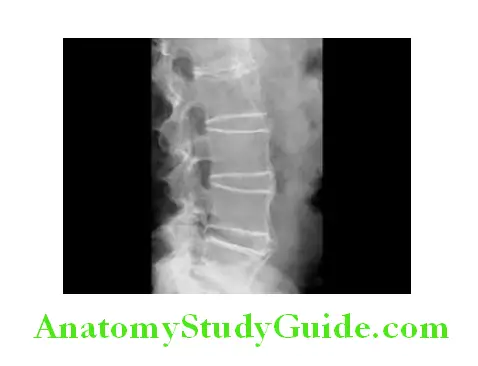

Radiographic Findings:

X-ray:

- Sacroiliac joint: The medial and lateral cortical margins of both sacroiliac joints lose definition owing to erosions. They show irregularity and loss of cortical margins (blurring of the cortical margins of the subchondral bone), erosions in the joint line, and ‘pseudowidening’ of the joint space. Subsequently, it shows subchondral sclerosis, joint space narrowing and fusion, bony ankylosis reflecting complete bony replacement of the sacroiliac joints.

- Lumbar spine: Radiographs of the spine may show anterior ‘squaring’ (loss of the normal anterior concavity of the lumbar vertebra), ‘shiny corners’ (subchondral sclerosis at the upper edge of the vertebral body), or even ‘barreling’ of one or more vertebral bodies due to erosion and sclerosis of the anterior corners of vertebrae with subsequent erosion. These are manifestations of enthesitis.

- Bridging syndesmophytes are areas of calcification that follow the outermost fibers of the annulus and may also be seen in AS. Progressive ossification may lead to formation of marginal syndesmophytes make the diagnosis clear. They are observed as bony bridges connecting successive vertebral bodies anteriorly and laterally. In advanced disease, ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament and facet joint fusion may also be seen. Eventually, the changes may result in a ‘bamboo spine’, so called because the multiple bridging syndesmophytes (bridging the intervertebral spaces) can mimic the appearance of bamboo.

- Diffuse osteoporosis of spine and atlantoaxial dislocation can be seen as late feature. Erosive changes may be observed in the symphysis pubis, the ischial tuberosities and peripheral joints.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI):

MRI is much more sensitive for detection of early sacroiliitis than X-ray and can also detect inflammatory changes in the lumbar spine.

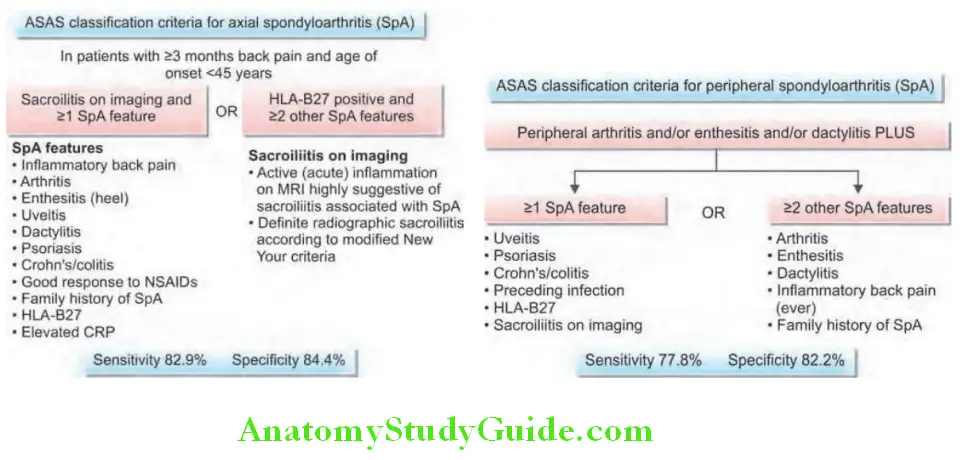

Diagnostic Criteria:

Modified New York Criteria (1984) for ankylosing spondylitis:

Clinical criteria:

- Low back pain and stiffness for >3 months that improve with exercise but are not relieved by rest

- Limitation of motion of the lumbar spine in both sagittal and frontal planes

- Limitation of chest expansion

Radiologic criteria:

- Sacroiliitis: Grade ≥2 bilateral or grade 3 or 4 unilateral

Grading:

- Definite AS (ankylosing spondylitis) if the radiologic criterion is associated with at least one clinical variable.

- Probable ankylosing spondylitis (AS) if:

- The three clinical criteria are present

- The radiologic criterion is present without the clinical criteria

Management:

- Early diagnosis is important to maintain posture and range of motion.

- Regular exercise is started with active and passive physiotherapy before syndesmophytes have formed.

- Symptomatic relief of pain and stiffness can be obtained with long-acting or slow-release NSAID or an NSAID suppository improves sleep, peripheral arthritis and enthesitis are managed with NSAIDs or local steroid injections. Indomethacin is the most effective drug and may be given up to a maximum dose of 100 mg/day. Systemic glucocorticoids have limited role.

- Sulfasalazine and methotrexate are useful to control effective for peripheral arthritis but not for spinal disease.

- Peripheral arthritis and enthesitis are managed with NSAIDs or local steroid injections. Rarely systemic corticosteroids may be necessary.

Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy:

Biologic agents, such as monoclonal antibodies to TNF-α (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, golimumab) or the soluble TNF receptor (etanercept) are options for patients with active ankylosing spondylitis who are not satisfactorily responded to NSAIDs. Duration of treatment is 2–3 years.

Dosage:

- Infliximab: 3–5 mg/kg body weight intravenously every 6–8 weeks.

- Etanercept: 25 mg subcutaneously twice a week initially/50 mg once weekly.

- Adalimumab: 40 mg biweekly by subcutaneous injection.

- Golimumab: 50 or 100 mg every 4 weeks, given by subcutaneous injection.

- Secukinumab is an interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody that has been approved for treatment of ankylosing spondylitis.

Others:

- Reconstructive surgery

- Pamidronate

- Control of uveitis by local steroids

Reactive Arthritis:

Question 35. Describe the etiology, clinical features, diagnosis and management of reactive arthritis.

(or)

Write a short note on Reiter’s syndrome.

Answer:

Reactive arthritis (ReA) refers to acute nonpurulent arthritis (aseptic arthritis) complicating an extra-articular infection elsewhere in the body, most typically enteric (GIT) or urogenital (GU tract) infections.

Classical triad of Reiter’s syndrome is:

- Nonspecific Urethritis

- Conjunctivitis

- Arthritis.

However the term is no longer in common use.

Etiology:

- GIT infections: Common enteric organisms that trigger include Salmonella typhimurium, Shigella flexneri, Yersinia enterocolitica, Escherichia coli, Clostridum difficile, and Chlamydia.

- GUT infection: Common urogential organisms are Chlamydia trachomatis or Ureaplasma urealyticum.

- More than 75% of ReA patients have the histocompatibility antigen HLA-B27.

Clinical Features:

- Age and gender: Predominantly a disease of young (18–40 years) men, with a male preponderance of 15:1.

- Constitutional symptoms are common and include fatigue, malaise, fever, and weight loss.

- Arthritis: Arthritis is typically an acute, asymmetrical, lower limb (e.g. knees, ankles, midtarsal and MTP joints) arthritis and occurs 1 to 3 weeks after the GIT or GUT infection, arthritis usually persists for 3–5 months.

- Enthesitis is common.

- Dactylitis or ‘sausage digit,’ is a diffuse swelling of a solitary finger or toe may also be seen. It is the result of inflammatory changes affecting the joint capsule, entheses, periarticular structures, and periosteal bone.

- Sacroiliitis may be seen in 25% patients.

- Extra-articular features

- Urogenital lesions: Urethritis and prostatitis in males, cervicitis or salpingitis in females.

- Mucocutaneous lesions: Circinate balanitis (a painless erythematous lesion of the glans penis), keratoderma blennorrhagica (hyperkeratotic lesions on the palms of the hands or the soles of the feet) and nail dystrophy.

- Ocular disease: Common and includes conjunctivitis, anterior uveitis and acute iritis.

- Others: Cardiac conduction defects, aortic regurgitation, central or peripheral nervous system lesions, and pleuropulmonary infiltrates.

- Usually a self-limiting course of 3–12 months. About 50% of patients develop recurrent bouts of arthritis and 15–30% develop chronic arthritis or sacroiliitis.

Investigations:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and acute-phase reactants: Usually raised.

- Peripheral blood: Anemia and polymorphonuclear leukocytosis.

- Synovial fluid: Characteristic synovial fluid is leukocyte-rich (>2000 white blood cells/mL with a predominance of neutrophils) and may contain multinucleated macrophages (Reiter’s cells).

- HLA-B27: Positive in more than 75% of cases.

- Serum tests for rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies: Negative.

- Urethritis: Confirmed in the ‘two-glass test’ by demonstration of mucoid threads in the first-void specimen that clears in the second specimen.

Radiological features:

- Shows periarticular osteoporosis, joint space narrowing and proliferative erosions in chronic or recurrent disease.

- Periostitis, especially of metatarsals, phalanges and pelvis, and large, fluffy calcaneal spurs at the insertion of the plantar fascia. Sacroiliitis (less common than ankylosing spondylitis) is often asymmetrical and sometimes unilateral.

Syndesmophytes are predominantly coarse and asymmetrical, often extending beyond the contours of the annulus

(‘non-marginal’).

Management:

- Acute attack:

- Treated with rest, oral NSAIDs and analgesics. Indomethacin, 75–150 mg/d in divided doses, is the initial treatment of choice.

- Intra-articular or local steroid injections and rarely systemic steroids in severe cases.

- Non-specific chlamydial urethritis: Treated with doxycycline or ciprofloxacin or a single dose of azithromycin course.

- No role of antibiotics in reactive spondyloarthropathy secondary to enteric infections.

- Sulfasalazine, azathioprine and methotrexate may be useful in patients with disabling relapsing and remitting arthritis.

- DMARDs: For patients with persistent marked symptoms, recurrent arthritis or severe keratoderma blennorrhagica.

- Anterior uveitis is a medical emergency and treated by topical, subconjunctival or systemic corticosteroids.

- TNF-α blocking agents are the drugs of next choice in severe and persistent disease.

Psoriatic Arthritis:

Question 36. Write short note on psoriatic arthritis.

Answer:

- Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a seronegative inflammatory arthritis that characteristically occurs in patient with psoriasis, a past or family history of psoriasis or with characteristic nail changes.

- Occurs in about 7–20% of patients of psoriasis.

Types: Wright and Moll described five patterns of psoriatic arthritis.

Newer pattern of psoriatic arthritis is described in HIV patients.

Patterns of psoriatic arthritis:

- Asymmetric inflammatory oligoarthritis

- Symmetric polyarthritis similar to RA (rheumatoid arthritis)

- Arthritis of the DIP (distal interphalangeal) joints

- Spondyloarthropathy ( sacroiliitis and spondylitis)

- Arthritis mutilans

Clinical Features:

It presents with pain and swelling affected joints and enthesitis.

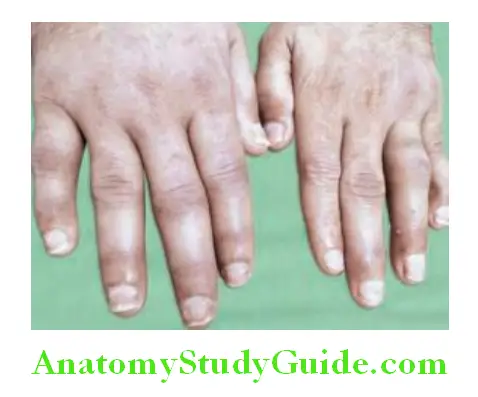

- Asymmetrical inflammatory oligoarthritis: Most characteristically occur in the hands and feet, when synovitis is associated with tenosynovitis, enthesitis and inflammation of intervening tissue resulting in a ‘sausage-shaped digit’ or dactylitis. Usually, less than four joints are involved (oligoarthritis).

- Symmetrical polyarthritis: It is more common in women and may strongly resemble RA.

- Arthritis of the DIP joints: Uncommon and affects men more than women. It involves finger DIP joints and surrounding periarticular tissues, and is accompanied by nail dystrophy.

- Psoriatic spondylitis: Presents similar to AS but with less severe involvement. It is typically unilateral or asymmetric in severity.

- Arthritis mutilans is a severe, deforming erosive arthritis accompanied by prominent cartilage and bone destruction results in marked instability of fingers and toes. The encasing skin appears invaginated and ‘telescoped’ and the finger can be pulled back to its original length.

- Enthesitis and tenosynovitis is common.

- Skin lesions: Characteristic skin lesion of psoriasis may be present.

- Nail changes: Psoriatic nail dystrophy, onycholysis, pitting, and hyperkeratosis observed in nearly 80% patients with arthritis.

- Uveitis: Unilateral or bilateral and is generally chronic.

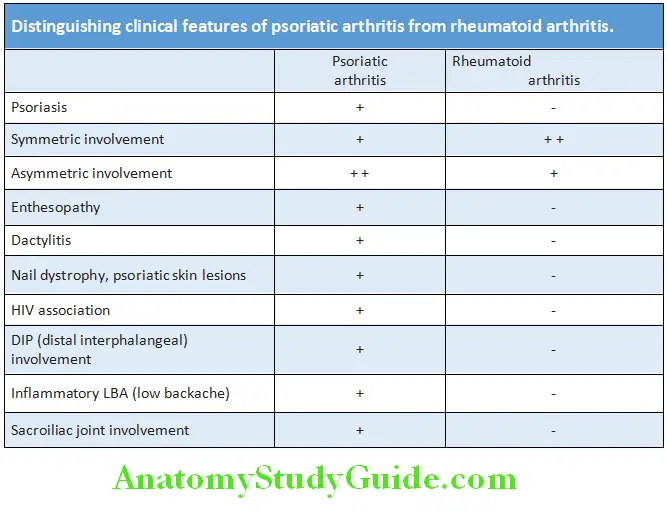

Question 37. Differentiate psoriatic arthritis from rheumatoid arthritis:

Answer:

Diagnosis:

- Acute phase reactants (ESR and CRP): Raised in active disease.

- Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies: Negative.

- Radiological findings: May be normal or show erosive change with joint space narrowing similar to those of RA, but osteoporosis is relatively less common. Distal interphalangeal joints may show ‘pencil-in-cup’ changes because of marked resorption of bone. Other findings include enthesitis with periosteal reaction, sacroiliitis and spondylitis.

- MRI and ultrasound with power Doppler are used to detect synovial inflammation and inflammation at the enthuses (enthesitis). Classification of Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) criteria is used for diagnosis which include skin lesions, nail changes, negative RF, dactylitis and juxta-articular bone formation—3 out of 5 need to be present.

Management:

- NSAIDs and analgesics may be sufficient to control symptoms in mild disease.

- Local synovitis may be treated by intra-articular corticosteroid injections.

- DMARDs for persistent synovitis unresponsive to conservative treatment. Sulfasalazine or methotrexate slows the development of joint damage.

- Anti-TNF-α agents (e.g. etanercept, golimumab, infliximab and adalimumab) should be considered for patients with active synovitis who respond inadequately to standard DMARDs.

- Hydroxychloroquine must be avoided as it can cause exfoliative skin reactions.

- Alefacept is a fusion protein of soluble lymphocyte function antigen 3 with Fc fragments of IgGIt is used for moderate-to-severe psoriasis and associated arthritis.

Enteropathic Arthritis:

Question 38. Write short note on spondyloarthropathy associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

Answer:

Also called as enteropathic arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease).

An acute inflammatory oligoarthritis occurs in 10–20% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). More often in patients with Crohn’s disease than in those with ulcerative colitis.

Clinical Features:

Peripheral arthritis:

- The arthritis is asymmetrical, inflammatory, nonerosive polyarthritis and mainly involves lower-limb joints (knees, ankles, hips).

- The clinical activity of the peripheral arthritis parallels the activity of the gut inflammation. Effective treatment of the GI disease usually controls the joint disease as well.

- It is not associated with HLA-B27 and follows a transient course.

Sacroiliitis:

- It is clinically and radiologically similar to classic AS.

- It can manifest before or after the onset of IBD and there is no correlation between activity of the spondylitis and bowel disease.

- HLA-B27 is found in 50% of patients and it follows a chronic course.

Others: Enthesitis, dactylitis and extra-articular manifestations of IBD.

Treatment:

- NSAIDs to be used cautiously because they may worsen diarrhea.

- Monoarthritis is treated by intra-articular corticosteroids.

- Sulfasalazine more effective as it may help both bowel and joint disease. Azathioprine and methotrexate may also be used.

- TNF-α blocking drug infliximab used for IBD can help the arthritis.

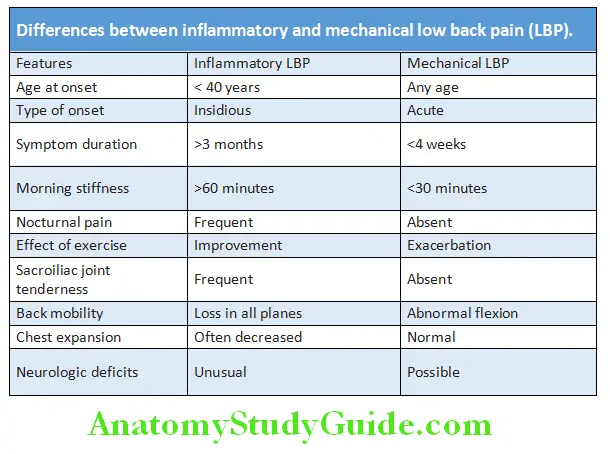

Differences between inflammatory and mechanical low back pain (LBP)

Question 39. Describe the clinical clues to differentiate inflammatory low back pain of ankylosing spondylitis from mechanical low back pain?

(or)

Differentiate between inflammatory versus mechanical back pain

Answer:

Adult Onset Still’S Disease (Aosd):

Question 40. Discuss the clinical features of adult onset still’s disease.

Answer:

AOSD is a rare inflammatory multisystem disease occurring in adults presenting as fever (quotidian/double quotidian), rash, arthritis, sore throat, hepatosplenomegaly and serositis (pleural and pericardial effusion).

The rash is classically evanescent, salmon-colored, macular or maculopapular which is usually nonpruritic and occurs with the fever. Arthritis and arthralgia mostly involve the knee, wrist and the ankle. Myalgia is seen in more than 50 percent of the cases. Macrophage activation syndrome, a rare and fatal complication of Adult Onset Still’s disease characterized by leukopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, transaminitis and intavascular coagulation.

Diagnosis:

Adult Onset Still’s disease (ASOD) is primarily a diagnosis of exclusion.

- Neutrophilia, thrombocytosis, raised ESR, CRP are present. Increased LDH and liver enzymes are seen