The Eye Ent And Neck Eye

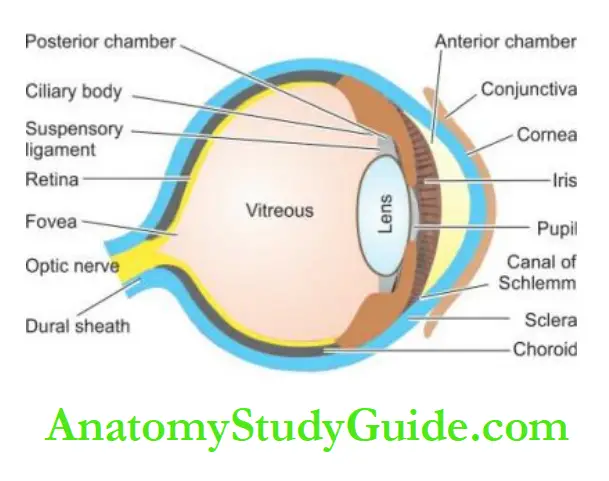

Normal Structure:

Table of Contents

- The structure of the eye is shown diagrammatically.

- The eyelids are covered externally by the skin and internally by conjunctiva which is reflected over the globe of the eye.

- The lacrimal glands which are compound racemose glands are situated at the outer upper angle of the orbit.

- The globe of the eye is composed of 3 layers: the cornea-sclera, choroid-iris, and retina.

- The cornea is covered by stratified epithelium which may be regarded as a continuation of the conjunctiva over the cornea.

- The subepithelial stroma consists of fibrous connective tissue, and the posterior endothelium-lined thin elastic membrane called Descemet’s membrane.

- The sclera is composed of dense fibrous tissue which is thickest at the back of the eyeball.

- The choroid is the vascular membrane in contact with the sclera.

- The choroid becomes thickened anteriorly forming the ciliary body, and the ciliary processes and contains the ciliary muscle.

- The iris is the continuation of the choroid which extends in front of the lens.

Read And Learn More: Systemic Pathology Notes

It is similar in structure to the choroid but contains pigment cells.

- The uveal tract consists of 3 parts the choroid and ciliary body posteriorly, and the iris anteriorly.

- The retina is part of the central nervous system and corresponds in extent to the choroid which it lines internally.

- The retina is composed of a number of layers of cells and their synapses which are of 3 types—external photoreceptor cells (rods and cones), an intermediate relay layer of bipolar cells, and an internal layer of ganglion cells with their axons running into the central nervous system.

- The central fovea is a specially differentiated spot in the retina posteriorly which consists only of photosensitive cones but is devoid of photoreceptor rods and blood vessels.

- Macula lutea or yellow spot surrounds the central fovea and though not as sensitive as the central fovea, it is more so than the other parts of the retina.

- At the optic disc, the fibres of the nerve fibre layer of the retina pass into the optic nerve.

- The lens is the biconvex mass of laminated transparent tissue with elastic capsules.

The anterior chamber is the space filled with the aqueous humour and is bounded by the cornea in front and the iris behind, with the anterior surface of the lens exposed in the pupil.

The posterior chamber containing aqueous humour is the triangular space between the back of the iris, the anterior surface of the lens and the ciliary body forming its apex at the pupillary margin.

The vitreous chamber is the large space behind the lens containing gelatinous material, the vitreous humour.

The main function of the eye is visual acuity which depends upon a transparent focusing system comprised of the cornea, lens, transparent media consisting of the aqueous and vitreous

humour, and a normal retinal and neural conduction system.

The cornea and lens receive their nutrient demands from the aqueous humour produced by the ciliary processes.

The intraocular pressure is normally 15-20 mmHg and depends upon the rate of aqueous production and on the resistance in the outflow system.

The following groups of diseases of the eye are discussed: congenital lesions, inflammatory conditions, vascular lesions, miscellaneous conditions, and tumours and tumour-like lesions.

Congenital Lesions:

Retrolental Fibroplasia (Retinopathy Of Prematurity): This is a developmental disorder occurring in premature infants who have been given oxygen therapy at birth.

- The basic defect lies in the developmental prematurity of the retinal blood vessels which are extremely sensitive to high doses of oxygen therapy.

- The peripheral retina is incompletely vascularized in such infants and exposure to oxygen results in vaso-obliteration.

- On stoppage of oxygen therapy, vast proliferation begins leading to neovascularisation, cicatrisation and retinal detachment.

Retinitis Pigmentosa: Retinitis pigmentosa is a group of systemic and ocular diseases of unknown aetiology, characterised by degeneration of the retinal pigment epithelium.

- The condition can have various inheritance patterns—autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive trait, or sex-linked recessive trait.

- The earliest clinical finding is night blindness due to loss of rods which may progress to total blindness.

Histologically, there is a disappearance of rods and cones of the photoreceptor layer of the retina, degeneration of retinal pigment epithelium and ingrowth of glial membrane on the optic disc.

Inflammatory Conditions:

- Inflammatory conditions of the eye are designated according to the tissue affected.

- ‘Uveitis’ is the commonly used term for the ocular inflammation of the uveal tract which is the most vascular tissue of the eye.

- However, the specific designation is used for the type of tissue of the eye inflamed.

- Some of the important examples are described below.

Stye (Hordeolum): Stye or ‘external hordeolum’ is an acute suppurative inflammation of the sebaceous glands of Zeis, the apocrine glands of Moll and the eyelash follicles.

- The less common ‘internal hordeolum’ is an acute suppurative inflammation of the meibomian glands.

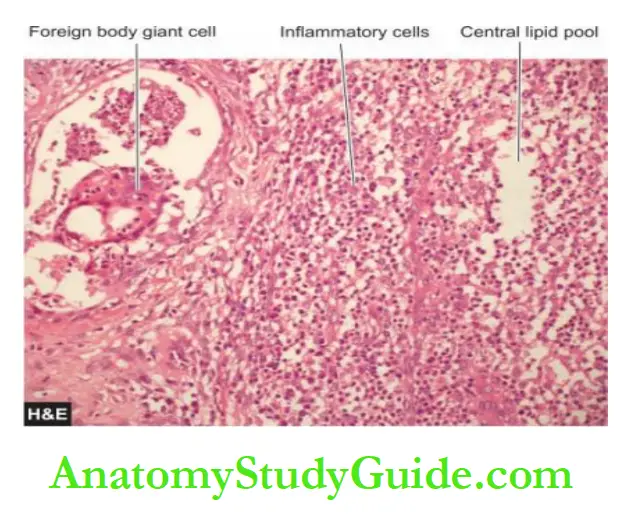

- Chalazion: Chalazion is a very common lesion and is a chronic inflammatory process involving the meibomian glands.

- It occurs as a result of obstruction to the drainage of secretions.

- The inflammatory process begins with the destruction of meibomian glands and ducts and subsequently involves the tarsal plate.

Histologically, the chalazion gives the appearance of a chronic inflammatory granuloma located in the tarsus and contains fat globules in the centre of the granulomas i.e. appearance of a lipogranuloma.

Endophthalmitis-Panophthalmitis: Endophthalmitis is an acute suppurative intraocular inflammation.

- Panophthalmitis is the term used for inflammation involving the retina, choroid and sclera and extending to the orbit.

- Infection may be of exogenous or endogenous origin. The exogenous agents may be bacteria, viruses or fungi introduced into the eye during an accidental or surgical perforating wound.

- The endogenous agents include opportunistic infections which may cause endophthalmitis via a haematogenous route e.g. candidiasis, toxoplasmosis, nocardiosis, aspergillosis and cryptococcosis.

- Upon healing, synechiae may develop which are adhesions between two iris and cornea (anterior synechiae), or between the iris and anterior surface of the lens (posterior synechiae).

Conjunctivitis And Keratoconjunctivitis: Conjunctiva and cornea are constantly exposed to various types of physical, chemical, microbial (bacteria, fungi, viruses) and allergic agents and hence prone to develop acute, subacute and chronic inflammations.

- In the acute stage, there is corneal oedema and infiltration by inflammatory cells, affecting the transparency of the cornea.

- In the more chronic form of inflammation, there is the proliferation of small blood vessels in the normally avascular cornea and infiltration by lymphocytes and plasma cells (pannus formation).

Trachoma And Inclusion Conjunctivitis (Tric): Both these conditions are caused by Chlamydia or TRIC agents. Trachoma is caused by C. trachomatis while inclusion conjunctivitis is caused by C. oculogenitalis.

- Trachoma is widely prevalent in developing countries of the world and is responsible for blindness on a large scale.

- In the early stage of infection, the trachoma agent that infects the conjunctival epithelium can be recognised in the smears by the intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies formed by the proliferating microorganisms within the cells.

- Later, the conjunctiva thickens due to dense chronic inflammatory cell infiltration along with lymphoid follicles and macrophages.

- The end result is extensive corneal and conjunctival cicatrisation accounting for blindness in trachoma.

- Inclusion conjunctivitis, though caused by an organism closely related to a trachoma agent, is a much less severe disease and causes mild keratoconjunctivitis.

Granulomatous Uveitis: A number of chronic granulomatous conditions may cause granulomatous uveitis.

- These include bacteria (e.g. tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis), viruses (e.g. CMV disease, herpes zoster), fungi (e.g. aspergillosis, blastomycosis, phycomycosis, histoplasmosis), and certain parasites (e.g. toxoplasmosis, onchocerciasis).

- Granulomatous uveitis is common in sarcoidosis as well.

Sympathetic Ophthalmia (Sympathetic Uveitis): This is an uncommon condition in which there is bilateral diffuse granulomatous uveitis following a penetrating injury to one eye.

- The condition probably results from an auto-sensitivity reaction to injured uveal tissue.

- It leads to severe visual loss in both eyes if not diagnosed and treated early.

Histologically, there is granulomatous uveal inflammation consisting of epithelioid cells and lymphocytes affecting both eyes.

- There is no necrosis and no neutrophilic or plasma cell infiltration.

- If the lens is also injured, it results in phaco anaphylactic endophthalmitis.

Vascular Lesions:

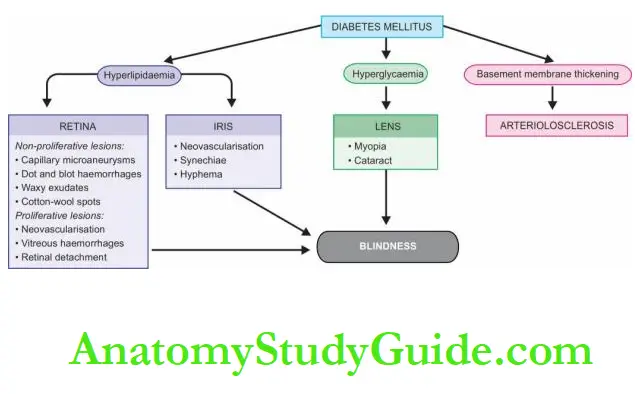

Diabetic Retinopathy: Diabetic retinopathy is an important cause of blindness. It is related to the degree and duration of glycaemic control.

- The condition develops in more than 60% of diabetics 15-20 years after the onset of the disease, and in about 2% of diabetics causes blindness.

- Other ocular complications of diabetes include glaucoma, cataract and corneal disease.

- Most cases of diabetic retinopathy occur over the age of 50 years.

- The risk is greater in type 1 diabetes mellitus than in type 2 diabetes mellitus, although in clinical practice there are more patients of diabetic retinopathy due to type 2 diabetes mellitus because of its higher prevalence.

- Women are more prone to diabetes as well as diabetic retinopathy.

- Diabetic retinopathy is directly correlated with Kimmelstiel-Wilson nephropathy.

Histologically, two types of changes are described in diabetic retinopathy—background (nonproliferative) and proliferative retinopathy.

1. Background (non-proliferative) retinopathy: This is the initial retinal capillary microangiopathy.

The following changes are seen:

- Basement membrane shows varying thickness due to increased synthesis of basement membrane substance.

- Degeneration of pericytes and some loss of endothelial cells are found.

- Capillary microaneurysms appear which may develop thrombi and get occluded.

- ‘Waxy exudates’ accumulate in the vicinity of microaneurysms especially in the elderly diabetics because of hyperlipidaemia.

- ‘Dot and blot haemorrhages’ in the deeper layers of the retina are produced due to the diapedesis of erythrocytes.

- Soft ‘cotton-wool spots’ appear on the retina which are microinfarcts of nerve fibre layers. ‘Scotomas’ appear from degeneration of nerve fibres and ganglion cells.

2. Proliferative retinopathy (retinitis proliferates): After many years, retinopathy becomes proliferative.

Severe ischaemia and chronic hypoxia for long period lead to the secretion of angiogenic factor by retinal cells and results in the following changes:

- Neovascularisation of the retina at the optic disc.

- Friability of newly-formed blood vessels causes them to bleed easily and results in vitreous haemorrhages. The proliferation of astrocytes and fibrous tissue around the new blood vessels.

- Fibrovascular and gliotic tissue contracts to cause retinal detachment and blindness.

- In addition to the changes in the retina, severe diabetes may cause diabetic iridopathy with the formation of adhesions between the iris and cornea (peripheral anterior synechiae) and between the iris and lens (posterior synechiae).

- Diabetics also develop cataracts of the lens at an earlier age than the general population.

- The pathogenesis of blindness in diabetes mellitus is schematically outlined.

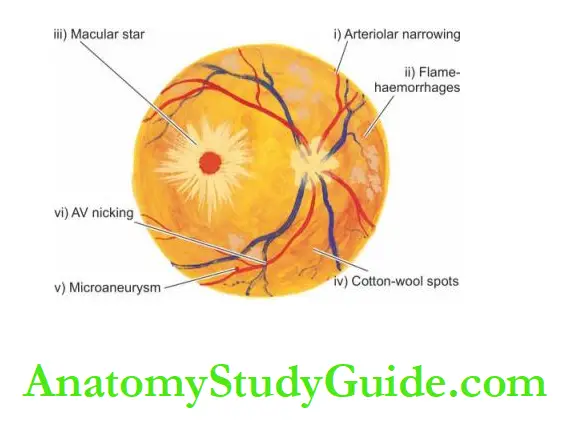

Hypertensive Retinopathy: In hypertensive retinopathy, the retinal arterioles are reduced in their diameter leading to retinal ischaemia.

In acute severe hypertension, as happens at the onset of malignant hypertension and in toxaemia of pregnancy, the vascular changes are in the form of spasms, while in chronic hypertension the changes are diffuse in the form of onionskin thickening of the arteriolar walls with narrowing of the lumina.

Features of hypertensive retinopathy include the following:

- Variable degree of arteriolar narrowing due to arteriolosclerosis.

- ‘Flame-shaped’ haemorrhages in the retinal nerve fibre layer.

- Macular star i.e. exudates radiating from the centre of the macula.

- Cotton-wool spots i.e. fluffy white bodies in the superficial layer of the retina.

- Microaneurysms.

- Arteriovenous nicking i.e. kinking of veins at sites where sclerotic arterioles cross veins.

- Hard exudates due to leakage of lipids and fluid into the macula.

- Hypertensive retinopathy is classified according to the severity of the above lesions from grade 1 to 4. More serious and severe changes with poor prognoses occur in higher grades of hypertensive retinopathy. Malignant hypertension is characterised by necrotising arteritis and fibrinoid necrosis of retinal arterioles.

Retinal Infarcts: Infarcts of the retina may result from thrombosis or embolism in the central artery of the retina, causing ischaemic necrosis of the inner two-thirds of the retina while occlusion of the posterior ciliary arteries causes ischaemia of the inner photoreceptor layer only.

- The usual causes of thrombosis and embolism are atherosclerosis, hypertension and diabetes.

- Occlusion of the central retinal vein produces haemorrhagic infarction of the entire retina.

Miscellaneous Conditions:

Pinguecula And Pterygium: Pinguecula is a degenerative condition of the collagen of the bulbar conjunctiva.

Clinically, the condition appears as raised yellowish lesions on the interpalpebral bulbar conjunctiva of both eyes in middle-aged and elderly patients.

- Histologically, there is characteristic basophilic degeneration of the subepithelial collagen of the conjunctiva.

- The overlying epithelium may show acanthosis, hyperkeratosis or dyskeratosis.

- Pterygium is a lesion closely related to pinguecula but differs from the latter by being located at the limbus and often involves the cornea; hence the lesion is more important clinically.

- Senile Macular Degeneration: Age-related degeneration of the macular region of the retina is an important cause of bilateral central visual loss in elderly people.

Histologically, in the early stage, there is an irregular thickening of the Bruch’s membrane that separates retinal pigment epithelium from the choroid, and there is degeneration of the photoreceptor and pigment epithelium.

Later, there is an ingrowth of capillaries into the choroid, exudation and haemorrhage under the retina which may eventually get organised, heal by fibrosis and result in permanent loss of central vision.

Retinal Detachment: Retinal detachment is the separation of the neurosensory retina from the retinal pigment epithelium.

- It may occur spontaneously in older individuals past 50 years of age or may be secondary to trauma in the region of the head and neck.

- Normally, the rods and cones of the photoreceptor layer are interdigitated with projections of the retinal pigment epithelium, but the two can separate readily in some disease processes.

There are 3 pathogenetic mechanisms of retinal detachment:

- Pathologic processes in the vitreous or anterior segment, cause traction on the retina.

- Collection of serous fluid in the sub-retinal space from inflammation or tumour in the choroid.

- Accumulation of vitreous under the retina through a hole or a tear in the retina.

Phthisis Bulbi: Phthisis bulbi is the end-stage of advanced degeneration and disorganisation of the entire eyeball in which the intraocular pressure is decreased and the eyeball shrinks.

The causes of such end-stage blind eye are trauma, glaucoma and intraocular inflammations.

Histologically, there is marked atrophy and disorganisation of all the ocular structures, and markedly thickened sclera. Even osseous metaplasia may occur.

Cataract: The cataract is the opacification of the normally crystalline lens which leads to gradual painless blurring of vision.

The various causes of cataracts are senility, congenital (e.g. Down syndrome, rubella, galactosaemia), traumatic (e.g. penetrating injury, electrical injury), metabolic (e.g. diabetes, hypoparathyroidism),

associated with drugs (e.g. long-term corticosteroid therapy), smoking and heavy alcohol consumption. The most common is, however, idiopathic senile cataract.

Histologically, the changes in the cataractous lens are similar irrespective of the underlying cause.

The lens fibres undergo degeneration, fragmentation and liquefaction but the central nucleus remains intact because it is quite sclerotic.

Glaucoma:

- Glaucoma is a group of ocular disorders that have in common increased intraocular pressure.

- Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of blindness because of the ocular tissue damage produced by raised intraocular pressure.

- In almost all cases, glaucoma occurs due to impaired outflow of aqueous humour, though there is a theoretical possibility of increased production of aqueous by the ciliary body causing glaucoma.

- The obstruction to the aqueous flow may occur as a result of developmental malformations (congenital glaucoma);

- or due to complications of some other diseases such as uveitis, trauma, intraocular haemorrhage and tumours (secondary glaucoma);

- or maybe primary glaucoma which is typically bilateral and is the most common type.

- There are 2 types of primary glaucoma—primary open-angle (chronic simple glaucoma) and primary angle-closure (acute congestive glaucoma).

- Primary open-angle glaucoma is a more common type and is usually a genetically-determined disease.

- Primary angle-closure glaucoma occurs due to a shallow anterior chamber and hence narrow-angle causing blockage of aqueous outflow.

- In all types of glaucoma, degenerative changes appear after some duration and eventually damage to the optic nerve and retina occurs.

Papilloedema: Papilloedema is oedema of the optic disc resulting from increased intracranial pressure.

- This is due to the anatomic continuation of the subarachnoid space of the brain around the optic nerve so that raised intracranial pressure is passed onto the optic disc area.

- In acute papilloedema, there is oedema, congestion and haemorrhage at the optic disc.

- In chronic papilloedema, there is degeneration of nerve fibres, gliosis and optic atrophy.

- Sjogren’s Syndrome: Sjogren’s syndrome is characterised by a triad of keratoconjunctivitis sicca, xerostomia (sicca syndrome) and rheumatoid arthritis.

- The condition occurs due to immunologically-mediated destruction of the lacrimal and salivary glands along with another autoimmune disease.

- Mikulicz’s Syndrome: This is characterised by inflammatory enlargement of lacrimal and salivary glands.

- The condition may occur with Sjögren’s syndrome, or with some diseases like sarcoidosis, leukaemia, lymphoma and macroglobulinaemia.

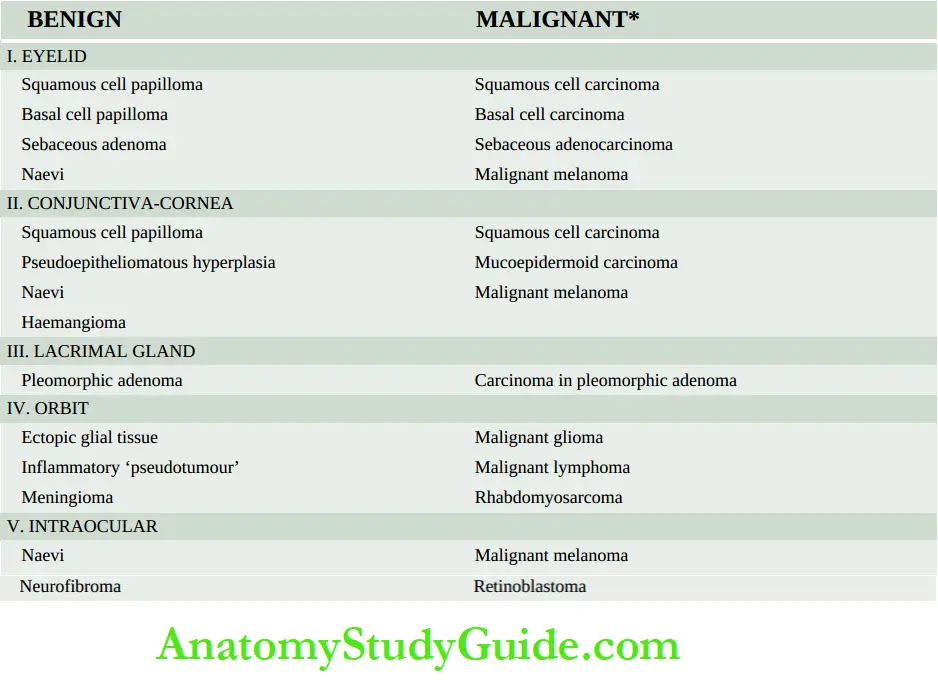

Tumours And Tumour-Like Lesions:

- The eye and its adnexal structures are the sites of a variety of benign and malignant tumours as well as tumour-like lesions. A brief list of such lesions.

- The morphology of many of these tumours and tumour-like lesions is identical to similar lesions elsewhere in the body.

- However, a few examples peculiar to the eye are described below.

Inflammatory Pseudotumours: These are a group of inflammatory enlargements, especially in the orbit, which clinically looks like tumours but surgical exploration and pathologic examination fail to reveal any evidence of neoplasm.

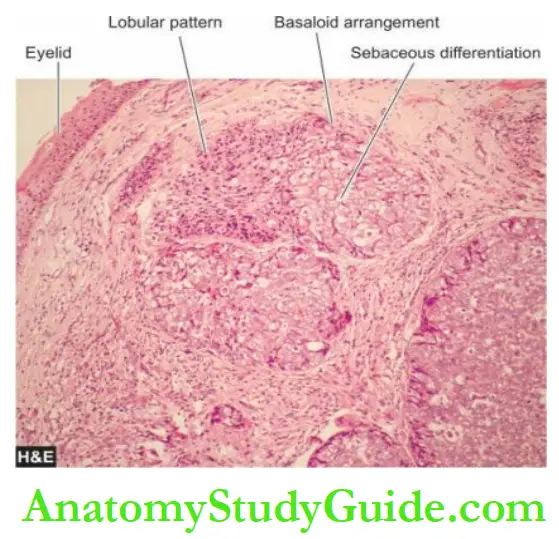

Morphologic Features: Grossly, the tumour appears as a localised or diffuse swelling of the tarsus, or maybe in the form of an ulcerated or papillomatous tumour at the lid margin.

Microscopically, the tumour may show well-differentiated lobules of tumour cells with sebaceous differentiation or maybe a poorly-differentiated tumour requiring confirmation by fat stains.

These tumours can metastasise to the regional lymph nodes as well as to distant sites.

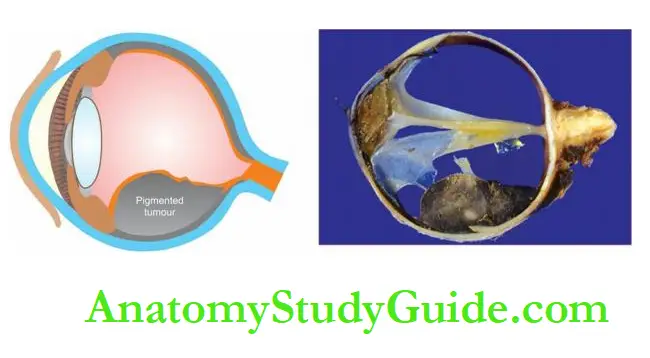

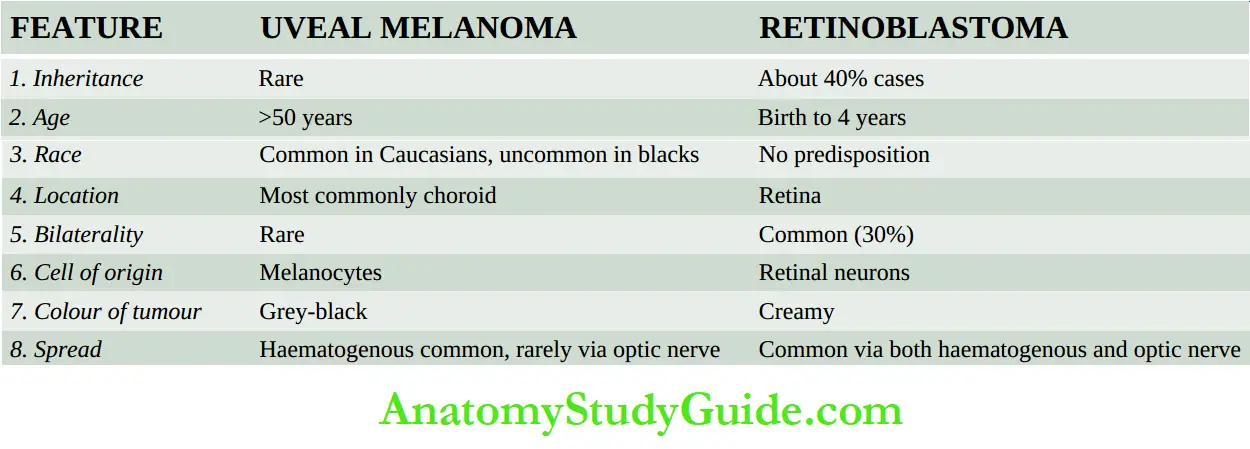

Uveal Malignant Melanoma: Malignant melanomas arising from neural crest-derived pigment epithelium of the uvea are the most common primary ocular malignancy in white adults in North America and Europe.

Morphologic Features: Grossly, the malignant melanoma appears as a pigmented mass, most commonly in the posterior choroid, and less often in the ciliary body and iris.

The mass projects into the vitreous cavity with the retina covering it.

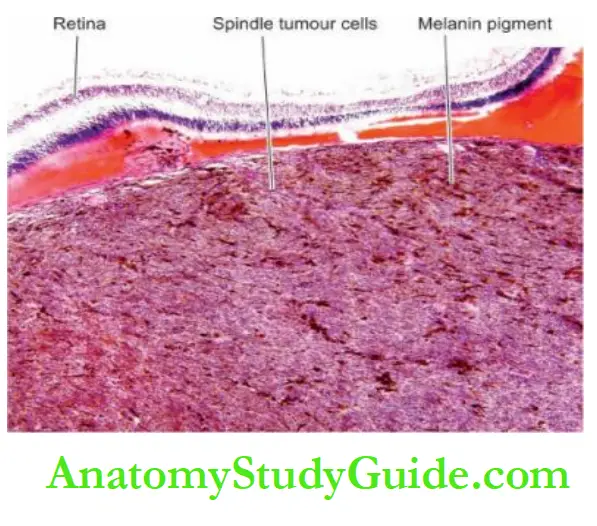

Microscopically, the age-old classification of Callender (1931) which has prognostic significance is still followed with some modifications:

1. Spindle A melanoma: is composed of uniform, spindle-shaped cells containing spindled nuclei.

Nucleoli are indistinct and mitotic figures are rare. Tumours of this type have the most favourable prognosis (85% 10-year survival).

2. Spindle B melanoma: is composed of larger and plump spindle-shaped cells with ovoid nuclei. Nucleoli are conspicuous and a few mitotic figures are present. These tumours carry a slightly worse prognosis (80% 10-year survival).

3. Epithelioid melanoma: consists of larger, irregular and pleomorphic cells with larger nuclei and abundant acidophilic cytoplasm.

These tumours are the most malignant of the uveal melanomas and have a poor prognosis (35% 10-year survival).

4. Mixed cell type melanomas have features of spindle cell type as well as of epithelioid cell type.

These are more common tumours and carry an intermediate prognosis (45% 10-year survival).

- In general, uveal malignant melanomas are usually slow-growing, late metastasising and have a better prognosis than malignant melanoma of the skin.

- Uveal melanomas spread via a haematogenous route and the liver is eventually involved in 90% of cases.

- Various indicators of a bad prognosis include large tumour size and epithelioid cell type.

Retinoblastoma: This is the most common malignant ocular tumour in children. It may be present at birth or recognised in early childhood before the age of 4 years.

- Retinoblastoma has some peculiar features. About 60% of cases of retinoblastoma are sporadic and the remaining 40% are familial.

- Familial tumours are often multiple and multifocal and transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait by the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene (RB) located on chromosome 13.

- Such individuals have a higher incidence of bilateral tumours and have an increased risk of developing a second primary tumour, particularly osteogenic sarcoma.

- Retinoblastoma may occur as a congenital tumour too.

- Clinically, the child presents with leukokoria i.e. white pupillary reflex.

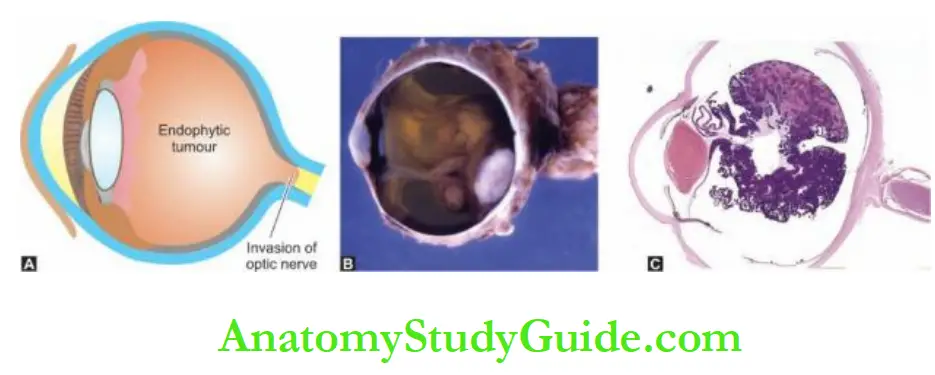

Morphologic Features: Grossly, the tumour characteristically appears as a white mass within the retina which may be partly solid and partly necrotic.

- The tumour may be endophytic when it protrudes into the vitreous, or exophytic when it grows between the retina and the pigment epithelium.

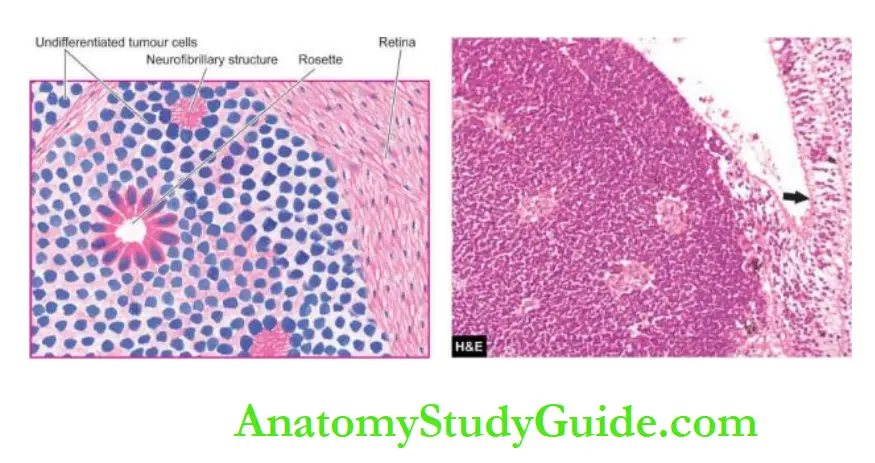

- Microscopically, the tumour is composed of undifferentiated retinal cells with a tendency towards the formation of photo-receptor elements.

- In the better-differentiated area, the tumour cells are characteristically arranged in rosettes.

- The rosettes may be of 2 types FlexnerWintersteiner rosettes characterised by small tumour cells arranged around a lumen with their nuclei away from the lumen, and Homer-Wright rosettes having a radial arrangement of tumour cells around the central neurofibrillary structure.

- The tumour shows wide areas of necrosis and calcification and dissemination in all directions—into the vitreous, under the retina, into the optic nerve and even into the brain.

- Besides direct spread, the tumour can spread widely via the haematogenous route as well. Prognosis is determined by the extent of local invasion and distant metastasis.

- Salient features of retinoblastoma are contrasted with those of uveal melanoma.

Metastatic Tumours:

- Ocular metastatic tumours are far more common than primary ocular malignant tumours, with choroid and iris being the preferential site for metastasis.

- Common primary tumours that metastasise to the eye are cancers of the breast in women and lung in men.

- Leukaemia and malignant lymphoma also commonly invade ocular tissues.

Feature Uveal Melanoma Retinoblastoma:

1. Inheritance Rare About 40% of cases

2. Age >50 years Birth to 4 years

3. Race is Common in Caucasians, uncommon in Blacks No predisposition

4. Location Most commonly choroid Retina

5. Bilaterality Rare Common (30%)

6. Cell of origin Melanocytes Retinal neurons

7. Colour of tumour Grey-black Creamy

8. Spread Haematogenous common, rarely via optic nerve Common via both haematogenous and optic nerve

Diseases of the Eye:

- Retinopathy of prematurity and retinitis pigmentosa are important congenital diseases of the eye.

- Various tissues of the eye are involved in inflammation e.g. stye (for sebaceous glands), chalazion (for meibomian glands), endophthalmitis (intraocular tissues), conjunctivitis, keratitis (for cornea), trachoma (for Chlamydial infection of conjunctiva), granulomatous uveitis and sympathetic ophthalmia (autosensitivity reaction).

- Retinal capillary vessels are affected in diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

- Pinguecula and pterygium are degeneration of collagen of the conjunctiva.

- Sebaceous carcinoma is a malignant tumour of the meibomian and Zeis’ glands.

- Uveal melanoma is slow-growing compared to cutaneous melanoma.

- Retinoblastoma is a malignant ocular tumour in children which disseminates widely.

Ear

Normal Structure:

- The ear is divided into 3 parts the external, middle and inner ear.

- The external ear comprises the auricle or pinna composed of cartilage, the external cartilaginous meatus and the external bony meatus.

- The external meatus is lined by stratified epithelium which is continued onto the external layer of the tympanic membrane.

- The tympanic membrane has a middle layer of elastic fibrous tissue and an inner layer of mucous membrane and is supported around the periphery by the annulus.

- The middle ear consists of 3 parts—the uppermost portion is the attic, the middle portion is the mesotympanum, and the lowermost portion is the hypotympanum.

- Besides, the middle ear has an opening, an eustachian tube, the mastoid antrum and cells, and the three ossicles (the malleus, incus and stapes).

- The middle ear is lined by a single layer of flat ciliated and nonciliated epithelium.

- The inner ear or labyrinth consists of a bony capsule embedded in the petrous bone and contains the membranous labyrinth.

- The bony capsule consists of 3 parts—posteriorly three semicircular canals, in the middle, is the vestibule, and anteriorly contains snail-like cochlea.

- Besides the function of hearing, the stimulation of the vestibular labyrinth can cause vertigo, nausea, vomiting and nystagmus.

- Two groups of conditions of the ear are discussed here: inflammatory and neoplastic.

Inflammatory And Miscellaneous Lesions:

Otitis Media This is the term used for inflammatory involvement of the middle ear.

- It may be acute or chronic. The usual source of infection is via the eustachian tube and the common causative organisms are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and β-

Streptococcus haemolyticus. - Otitis media may be suppurative, serous or mucoid. Acute suppurative otitis media (SOM) clinically presents as tense and hyperaemic tympanic membrane along with pain and tenderness and sometimes mastoiditis as well.

- Chronic SOM manifests clinically as a draining ear with a perforated tympanic membrane and partially impaired hearing.

- Serous or mucoid otitis media refers to the non-suppurative accumulation of serous or thick viscid fluid in the middle ear.

- These collections of fluid are encountered more often in children causing hearing problems and occur due to obstruction of the eustachian tube.

Relapsing Polychondritis: This is an uncommon autoimmune disease characterised by complete loss of glycosaminoglycans resulting in the destruction of the cartilage of the ear, nose, eustachian tube, larynx and lower respiratory tract.

- Histologically, the perichondral areas show acute inflammatory cell infiltration and destruction and vascularisation of the cartilage.

- The late stage shows lymphocytic infiltration and fibrous replacement.

Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Chronica Helicis: This condition involves the external ear superficially and presents as a ‘painful nodule of the ear’.

- The skin in this location is in direct contact with the cartilage without a protective subcutaneous layer.

- Histologically, the nodule shows epithelial hyperplasia with degeneration of the underlying collagen, chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, vascular proliferation and fibrosis.

- Cauliflower Ear: This is an acquired deformity of the external ear due to degeneration of cartilage as a result of repeated trauma as occurs in boxers and wrestlers.

- Histologically, there is the destruction of cartilage forming a homogeneous matrix (chondromalacia) and fibrous replacement.

Otosclerosis:

- This is a dystrophic disease of the labyrinth of the temporal bone.

- The footplate of stapes first undergoes fibrous replacement and is subsequently replaced by sclerotic bone.

- The exact etiology is not known but the condition has familial preponderance and autosomal dominant trait.

- It is seen more commonly in young males as a cause of the sensorineural type of deafness.

Tumours And Tumour-Like Lesions:

- Tumours and tumour-like conditions are relatively more common in the external than in the middle and inner ear.

- Many of the lesions seen in the external ear are similar to those seen in the skin e.g. tumour-like lesions such as epidermal cysts; benign tumours like naevi and squamous cell papilloma; and malignant tumours such as basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and malignant melanoma.

- However, tumours and tumour-like lesions which are specific to the ear are described below.

These include the following:

- In the external ear—aural (otic) polyps and cerumen-gland tumours.

- In the middle ear—cholesteatoma (keratoma) and jugular paraganglioma (glomus jugulare tumour).

- In the inner ear—acoustic neuroma.

Aural (Otic) Polyps:

Aural or otic polyps are tumour-like lesions arising from the middle ear as a complication of the chronic otitis media and project into the external auditory canal.

Histologically, they are composed of chronic inflammatory granulation tissue and are often covered by metaplastic squamous epithelium or pseudostratified columnar epithelium.

Cerumen-Gland Tumours:

Tumours arising from cerumen-secreting apocrine sweat glands of the external auditory canal are cerumen-gland adenomas or cerumen-gland adenocarcinomas and are counter-parts of sweat gland tumours (hidradenoma and adenocarcinoma) of the skin.

Both these tumours may invade the temporal bone.

Cholesteatoma (Keratoma): This is a post-inflammatory ‘pseudotumour’ found in the middle ear or mastoid air cells. There is an invariable history of acute or chronic otitis media.

A marginal perforation is generally present through which the squamous epithelium enters the middle ear and results in the exfoliation of squamous and the formation of the keratin.

Rarely, it may be a primary lesion arising from embryonal rests of squamous epithelium in the temporal bone.

Histologically, the lesion consists of a cyst containing abundant keratin material admixed with cholesterol crystals and a large number of histiocytes.

In advanced cases, there may be pressure erosion of the bone.

Jugular Paraganglioma (Glomus Jugulare Tumour, Nonchromaffin Paraganglioma): Tumours originating from parasympathetic ganglia are called ‘paraganglioma’ and are named according to the location of the tissue of origin.

The one arising from glomus jugulare bodies of the middle ear (jugulotympanic bodies) is called jugular paraganglioma or chemodectoma or non-chromaffin paraganglioma and is the most common benign tumour of the middle ear.

Histologically, similar tumours are seen in the carotid bodies and vagus.

Acoustic Neuroma (Acoustic Schwannoma): This is a tumour of Schwann cells of the 8th cranial nerve.

- It is usually located in the internal auditory canal and cerebellopontine angle.

- It is a benign tumour similar to other schwannomas but by virtue of its location and large size, may produce compression of the important neighbouring tissues leading to deafness, tinnitus, paralysis of 5th and 7th nerves, compression of the brainstem and hydrocephalus.

- Some recent epidemiologic studies have hinted towards the probable association of acoustic neuroma with the long-term use of mobile phones.

Diseases of the Ear:

- Otitis media is an acute and chronic inflammation of the middle ear.

- Aural polyps and cholesteatoma may develop following chronic SOM.

- Acoustic neuroma is a benign tumour of the 8th cranial nerve and is similar to schwannoma.

Nose And Paranasal Sinuses

Normal Structure:

- The external nose and the septum are composed of bone and cartilage.

- On the lateral wall of the nasal cavity, there is a system of 3 ridges on each side known as conchae or turbinates—the inferior, middle and superior.

- The nasal accessory sinuses are air spaces in the bones of the skull and communicate with the nasal cavity.

- They are the frontal air sinus, maxillary air sinus and anterior ethmoid air cells, comprising the anterior group, while posterior ethmoidal cells and sphenoidal sinus form the posterior group.

- The anterior group drains into the middle meatus while the posterior group drains into the superior meatus and the sphenoethmoidal recess.

- Microscopically, nasal mucous membranes as well as the lining of the nasal sinus are lined by respiratory epithelium (pseudostratified columnar ciliated cells).

- Mucous and serous glands lie under the mucous membrane. Besides, the upper and middle turbinate processes and the upper third of the septum are covered with olfactory mucous membranes.

- The main physiologic functions of the nose are smell, filtration, humidification and warming of the air being breathed.

- Inflammatory and neoplastic lesions of these organs are discussed here.

Inflammatory Conditions

Acute Rhinitis (Common Cold): Acute rhinitis or common cold is the common inflammatory disorder of the nasal cavities that may extend into the nasal sinuses.

- It begins with rhinorrhoea, nasal obstruction and sneezing.

- Initially, the nasal discharge is watery, but later it becomes thick and purulent.

- The etiologic agents are generally adenoviruses that evoke catarrhal discharge.

- Chilling of the body is a contributory factor. Secondary bacterial invasion is common.

- The nasal mucosa is oedematous, red and thickened.

- Microscopically, there are numerous neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells and some eosinophils with abundant oedema.

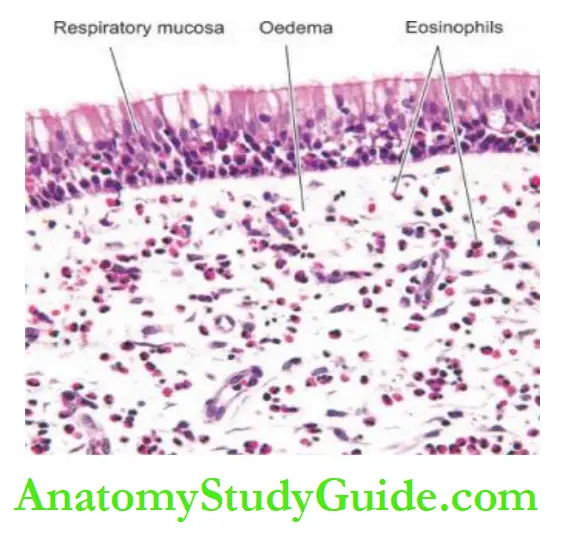

- Allergic Rhinitis (Hay Fever): Allergic rhinitis occurs due to sensitivity to allergens such as pollens.

- It is an IgE-mediated immune response consisting of an early acute response due to degranulation of mast cells, and a delayed prolonged response in which there is infiltration by

leucocytes such as eosinophils, basophils, neutrophils and macrophages accompanied by oedema. - Sinusitis: Acute sinusitis is generally a complication of acute or allergic rhinitis and is rarely secondary to dental sepsis.

- The ostia are occluded due to inflammation and oedema and the sinuses are full.

- ‘Mucocele’ is the filling up of the sinus with mucus while ‘empyema’ of the sinus occurs due to the collection of pus.

- Acute sinusitis may become chronic due to incomplete resolution of acute inflammation and from damage to the mucous membrane.

Sinusitis may rarely spread to produce osteomyelitis and intracranial infections.

- Nasal Polyps: Nasal polyps are common and are pedunculated grape-like masses of tissue.

- They are the end result of prolonged chronic inflammation causing polypoid thickening of the mucosa.

- They may be allergic or inflammatory. They are frequently bilateral and the middle turbinate is the common site.

- Antrochoanal polyps originate from the mucosa of the maxillary sinus and appear in the nasal cavity.

- Morphologically, nasal and antrochoanal polyps are identical.

- Grossly, they are gelatinous masses with a smooth and shining surfaces.

- Microscopically, they are composed of loose oedematous connective tissue containing some mucous glands and varying numbers of inflammatory cells like lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils.

- Allergic polyps have plenty of eosinophils and hyperplasia of mucous glands.

- Both inflammatory and allergic polyps are covered by respiratory epithelium which may show squamous metaplasia.

- Nasal polyps may have superimposed fungal infections.

- The underlying stroma is vascularised and oedematous and contains inflammatory cells with a prominence of eosinophils.

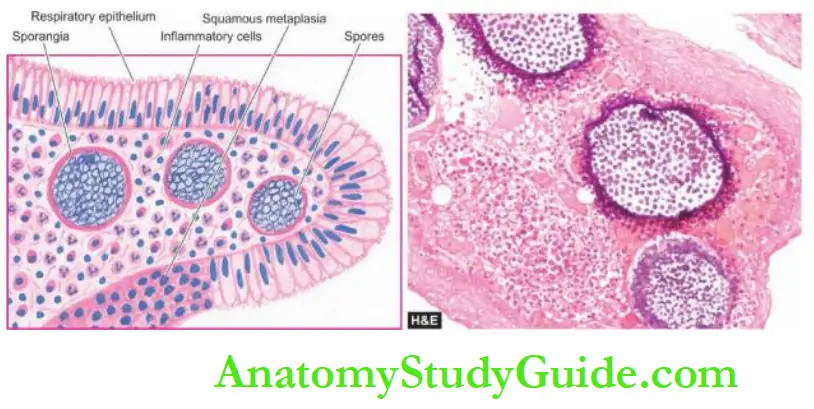

- Rhinosporidiosis: Rhinosporidiosis is caused by a fungus, Rhinosporidium seekers.

- Typically it occurs in a nasal polyp but may be found in other locations like the nasopharynx, larynx and conjunctiva.

The disease is common in India and Sri Lanka and sporadic in other parts of the world.

Microscopically, besides the structure of inflammatory or allergic polyp, a large number of organisms of the size of erythrocytes with chitinous walls are seen in the thick-walled sporangia.

- Each sporangium may contain a few thousand spores. On rupture of a sporangium, the spores are discharged into the submucosa or onto the surface of the mucosa.

- The intervening tissue consists of inflammatory granulation tissue (plasma cells, lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils) while the overlying epithelium shows hyperplasia, focal thinning and occasional ulceration.

Rhinoscleroma: This is a chronic destructive inflammatory lesion of the nose and upper respiratory airways caused by dicloxacillin, Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis.

- The condition is endemic in parts of Africa, America, South Asia and Eastern Europe.

- The condition begins as a common cold and progresses to the atrophic stage, and then into the nodular stage characterised by small tumour-like submucosal masses.

- Histologically, there is extensive infiltration by foamy histiocytes containing the organisms (Mikulicz cells) and other chronic inflammatory cells like lymphocytes and plasma cells.

- Granulomas: Many types of granulomatous inflammations may involve the nose.

- These include tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis, aspergillosis, mucormycosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis and lethal midline granuloma.

1. Tuberculosis or lupus: of the nose is uncommon and occurs secondary to pulmonary tuberculosis and usually produces ulcerative lesions on the anterior part of the septum of the nose.

2. Leprosy: begins as a nodule that may ulcerate and perforate the septum.

3. Syphilis: may involve the nose in congenital form causing destruction of the septum, or in acquired tertiary syphilis in the form of gummas perforating the septum.

In either case, characteristic saddle-nose deformity occurs due to the collapse of the bridge of the nose.

4. Aspergillosis: may involve the paranasal sinuses where the septate hyphae grow to form a mass called aspergilloma.

5. Mucormycosis: is an opportunistic infection caused by Mucorales which are non-septate hyphae and involve the nerves and blood vessels.

6. Wegener’s granulomatosis: is a form of necrotising vasculitis with granuloma formation affecting the upper respiratory tract, lungs and kidneys.

In 15-50% of cases, the condition may evolve into malignant lymphoma.

7. Lethal midline granuloma or polymorphic reticulosis: is a rare and lethal lesion of the upper respiratory tract that causes extensive destruction of cartilage and necrosis of tissues and does not respond to antibiotic treatment.

- Besides the necrosis, lymphoid infiltrates of pleomorphic and atypical cells admixed with small lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages are seen.

- Currently, the condition is considered to be a nasal-type extranodal T-cell lymphoma that may respond to chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Tumours:

- The tumours of the nose, nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses are uncommon.

- However, benign and malignant tumours of epithelial as well as mesenchymal origin can occur.

Benign Tumours:

Capillary Haemangioma: Capillary haemangioma of the septum of the nose is a common benign lesion and is similar to its counterparts elsewhere.

If the surface is ulcerated and the lesion contains inflammatory cell infiltrate, it resembles inflammatory granulation tissue and is called ‘haemangioma of granulation tissue type’ or ‘granuloma pyogenic.

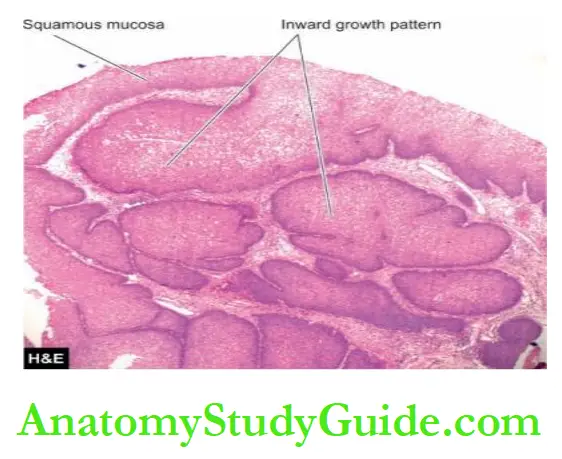

Sinonasal Papillomas: Papillomas may occur in the nasal vestibule, nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses.

- They are mainly of 2 types—fungiform papilloma with exophytic growth, and inverted papilloma with everted growth, also called Schneiderian papilloma.

- Inverted papilloma due to downward growth must not be mistaken for carcinoma.

- Papillomas of either type may be lined with various combinations of epithelia: respiratory, squamous and mucous types.

Malignant Tumours Olfactory Neuroblastoma Or Esthesioneuroblastoma: It occurs over the olfactory mucosa as a polypoid mass that may invade the paranasal sinuses or skull.

It is a highly malignant small-cell tumour of neural crest origin that may, at times, be indistinguishable from other small-cell malignancies like rhabdomyosarcoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, lymphoma or Ewing’s sarcoma.

Rosettes are found in about 10% of tumours.

Carcinomas: Carcinomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses are called sinonasal carcinomas.

- Most commonly, these are squamous cell carcinomas of varying grades of differentiation; others are adenocarcinoma, small cell neuroendocrine type etc.

- They are seen more commonly in the elderly with a history of heavy smoking and severe chronic sinusitis and in persons engaged in certain occupations e.g.

- in nickel refinery workers and in woodworkers. The tumour extends locally to involve the surrounding bone and soft tissues and also metastasises widely.

- Other types of malignancies found uncommonly in this location are adenoid cystic carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, lymphoma and malignant melanoma.

Diseases of Nose and Paranasal Sinuses:

- Nasal polyps are pedunculated masses which are commonly allergic types.

- Rhinosporidiosis presents as a nasal polyp and has sporangia of fungus.

- Common benign tumours of this region are haemangioma and papilloma.

- Common malignant tumours are sinonasal carcinoma (usually squamous cell type) and olfactory neuroblastoma.

Pharynx

Normal Structure:

The pharynx has 3 parts—the nasopharynx, the oropharynx (pharynx proper) and the laryngopharynx.

The whole of the pharynx is lined by stratified squamous epithelium. The lymphoid tissue of the pharynx is comprised of the tonsils and adenoids. Inflammation and neoplasms of the pharynx and nasopharynx are discussed here.

Inflammatory Conditions:

Ludwig’s Angina: This is a severe, acute streptococcal cellulitis involving the neck, tongue and back of the throat.

The condition was more common in the pre-antibiotic era as a complication of compound fracture of the mandible and periapical infection of the molars.

The condition often proves fatal due to glottic oedema, asphyxia and severe toxaemia.

Vincent’S Angina: Vincent’s angina is a painful condition of the throat characterised by local ulceration of the tonsils, mouth and pharynx.

The causative organism is Vincent’s bacillus. The condition may occur as an acute illness involving the tissues diffusely or as a chronic form consisting of ulceration of the tonsils.

Diphtheria: Diphtheria is an acute communicable disease caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae.

It usually occurs in children and results in the formation of a yellowish-grey pseudomembrane in the mucosa of the nasopharynx, oropharynx, tonsils, larynx and trachea.

C.diphtheriae elaborates an exotoxin that causes necrosis of the epithelium which is associated with abundant fibrinopurulent exudate resulting in the formation of pseudomembrane.

Absorption of the exotoxin in the blood may lead to more distant injurious effects such as myocardial necrosis, polyneuritis, and parenchymal necrosis of the liver, kidney and adrenals.

The constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, malaise, obstruction of the airways and dyspnoea are quite marked.

The condition has to be distinguished from the membrane of streptococcal infection.

Tonsillitis: Tonsillitis caused by staphylococci or streptococci may be acute or chronic. Acute tonsillitis is characterised by enlargement, redness and inflammation.

Acute tonsillitis may progress to acute follicular tonsillitis in which crypts are filled with debris and pus giving it a follicular appearance.

Chronic tonsillitis is caused by repeated attacks of acute tonsillitis in which case the tonsils are small and fibrosed.

Acute tonsillitis may pass on to tissues adjacent to the tonsils to form peritonsillar abscess or quinsy.

Peritonsillar Abscess (Quinsy): Peritonsillar abscess or quinsy occurs as a complication of acute tonsillitis.

The causative organisms are staphylococci or streptococci which are associated with infection of the tonsils.

The patient complains of acute pain in the throat, trismus, difficulty in speech and inability to swallow.

The glands behind the angle of the mandible are enlarged and tender.

Besides the surgical management of the abscess, the patient must be advised of tonsillectomy because quinsy is frequently recurrent.

Retropharyngeal Abscess: The formation of an abscess in the soft tissue between the posterior wall of the pharynx and the vertebral column is called a retropharyngeal abscess.

It occurs due to infection of the retropharyngeal lymph nodes.

It is found in debilitated children. A chronic form of the abscess in the same location is seen in tuberculosis of the cervical spine (cold abscess).

Tumours:

There are 4 main tumours of note in the pharynx, one benign—nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, and three malignant—nasopharyngeal carcinoma, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and malignant lymphoma.

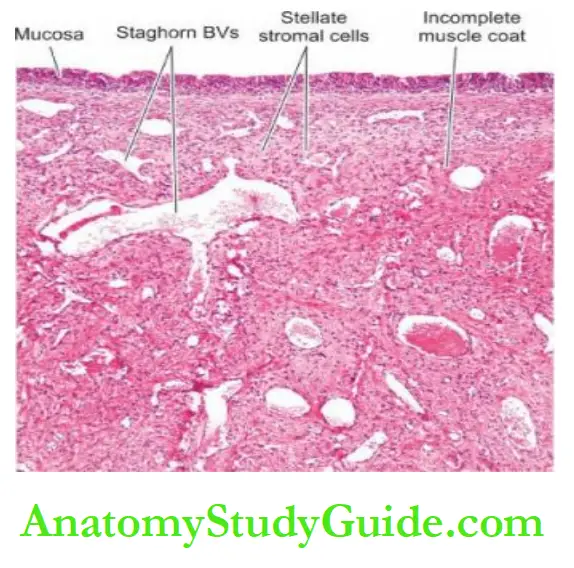

Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma: This is a peculiar tumour that occurs exclusively in adolescent males (10-20 years of age) suggesting the role of testosterone hormone in its production.

Though a benign tumour of the nasopharynx, it may grow into paranasal sinuses, cheek and orbit but does not metastasise.

Microscopically, the tumour is composed of 2 components as the name suggests—numerous small endothelium-lined vascular spaces and the stromal cells which are myofibroblasts.

The androgen dependence of the tumour is confirmed by a demonstration by immunostaining for androgen receptors in 75% of cases.

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is common cancer in South-East Asia, especially prevalent in people of Chinese descent under 45 years of age.

Genetic susceptibility and the role of the Epstein-Barr virus are considered important factors in its aetiology.

In fact, the EBV genome is found virtually in all cases of nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

The primary tumour is generally small and undetected, while the metastatic deposits in the cervical lymph nodes may be large.

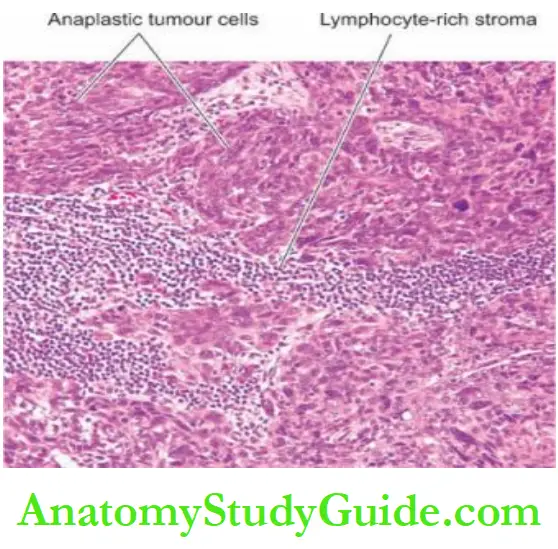

Microscopically, nasopharyngeal carcinoma has 3 histologic variants Non-keratinising squamous cell carcinoma

- Keratinising squamous cell carcinoma

- Undifferentiated (transitional cell) carcinoma

Non-keratinising and keratinising squamous cell carcinomas are identical in morphology to typical tumours in other locations.

Undifferentiated carcinoma, also called transitional cell carcinoma is characterised by masses and cords of cells which are polygonal to spindled and have large vesicular nuclei.

A variant of undifferentiated carcinoma is ‘lymphoepithelioma’ in which undifferentiated carcinoma is infiltrated by abundant nonneoplastic mature lymphocytes.

Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma: Also termed as botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma, this is one of the common malignant tumours in children but can also occur in adults.

The lesion is highly cellular and mitotically active. Other locations include the vagina, orbit, middle ear, oral cavity, retroperitoneum and bile duct.

Malignant Lymphoma: The lymphoid tissue of the nasopharynx and tonsils may be the

site for the development of malignant lymphomas which resemble similar tumours elsewhere in the body.

Diseases of the Pharynx:

Tonsillitis is a common condition and may be acute or chronic inflammation of the tonsils.

Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma is a peculiar tumour in adolescent males composed of numerous vascular spaces and myofibroblastic stromal cells.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is an EBV-related squamous or transitional cell tumour.

Embryonal (botryoid) rhabdomyosarcoma is a malignant tumour of children seen in the nasopharynx, vagina, orbit etc.

Larynx

Normal Structure:

The larynx is composed of cartilage which is bound together by ligaments and muscles and is covered by mucous membrane.

The cartilages of the larynx are of 2 types—unpaired and paired.

- The unpaired laryngeal cartilages are epiglottis, thyroid cartilage (Adam’s apple) and cricoid

cartilage. - The paired cartilages are the arytenoid cartilages which play an important part in the movement of vocal cords.

The larynx as well as the trachea are lined by respiratory epithelium, except over the true vocal cords and the epiglottis, which are lined by stratified squamous epithelium.

Inflammation and tumours of the larynx are discussed here.

Inflammatory Conditions:

Acute Laryngitis: This may occur as a part of the upper or lower respiratory tract infection.

Atmospheric pollutants like cigarette smoke, exhaust fumes, industrial and domestic smoke etc predispose the larynx to acute bacterial and viral infections.

Streptococci and H. influenzae cause acute epiglottitis which may be life-threatening.

Acute laryngitis may occur in some other illnesses like typhoid, measles and influenza.

Acute pseudomembranous (diphtheric) laryngitis occurs due to infection with C. diphtheriae.

Chronic Laryngitis: Chronic laryngitis may occur from repeated attacks of acute inflammation, excessive smoking, chronic alcoholism or vocal abuse.

The surface is granular due to swollen mucous glands. There may be extensive squamous metaplasia due to heavy smoking, chronic bronchitis and atmospheric pollution.

Tuberculous Laryngitis: Tuberculous laryngitis occurs secondary to pulmonary tuberculosis. Typical caseating tubercles are present on the surface of the larynx.

Acute Oedema Of The Larynx: This hazardous condition is an acute inflammatory condition, causing swelling of the larynx that may lead to airway obstruction and death by suffocation.

Acute laryngeal oedema may occur due to trauma, inhalation of irritants, drinking hot fluids or may be infective in origin.

Tumours:

Both benign and malignant tumours occur in the larynx. Common examples of benign tumours are papillomas and polyps, while laryngeal carcinoma is an important example of malignant tumours.

Laryngeal Papilloma And Papillomatosis: Juvenile laryngeal papillomas are found in children or adolescents and are often multiple, while adults have usually a single lesion.

Multiple juvenile papillomas may undergo spontaneous regression at puberty.

Human papillomavirus (HPV type 11 and 6) has been implicated in the aetiology of papillomas of the larynx.

Grossly, the lesions appear as warty growths on the true vocal cords, and epiglottis and sometimes extend to the trachea and bronchi.

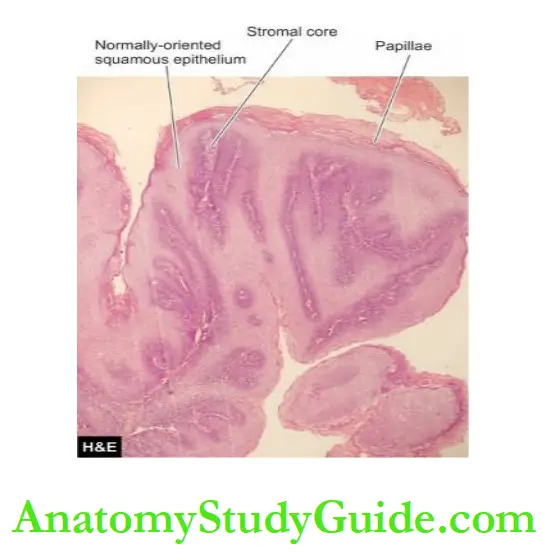

Microscopically, papillomas are composed of finger-like papillae, each papilla contains a fibrovascular core covered by stratified squamous epithelium.

Laryngeal Nodules: Laryngeal nodules or polyps are seen mainly in adults and are found more often in heavy smokers and in individuals subjected to vocal abuse.

Therefore, they are known by various synonyms like singers’ nodes, preachers’ nodes, and screamers’ nodes. The patients have characteristic progressive hoarseness.

Grossly, it is a small lesion, less than 1 cm in diameter, rounded, smooth, usually sessile and polypoid swelling on the true vocal cords.

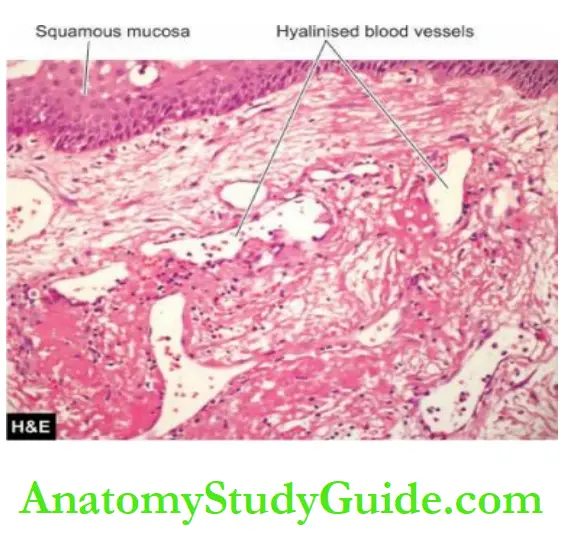

Microscopically, the nodules have prominent oedema with sparse fibrous tissue and numerous irregular and dilated vascular channels.

Sometimes, the subepithelial basement membrane is thickened, resembling amyloid material.

Laryngeal Carcinoma: Cancer of the larynx in 99% of cases is squamous cell carcinoma.

Rarely, adenocarcinoma and sarcoma are encountered. Squamous carcinoma of the larynx occurs in males beyond 4th decade of life.

The important etiologic factor is heavy smoking of cigarettes, cigar or pipes; other factors include excessive alcohol consumption, radiation and asbestos exposure.

Carcinoma of the larynx is conventionally classified into extrinsic which arises or extends outside the larynx and intrinsic which arises within the larynx.

However, based on the anatomic location, laryngeal carcinoma is classified as under:

- Glottic is the most common location, found in the region of true vocal cords and anterior and posterior commissures.

- Supraglottic involving ventricles and arytenoids.

- Subglottic in the walls of subglottis.

- The marginal zone between the tip of the epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds.

- Laryngo-(hypo-) pharynx in the pyriform fossa, postcricoid fossa and posterior pharyngeal wall.

Grossly, glottic carcinoma is the most common form and appears as a small, pearly white, plaque-like thickening that may be ulcerated or fungated.

Microscopically, keratinising and non-keratinising squamous carcinomas of varying grades are found.

Generally, carcinoma of the supraglottic and subglottic regions tends to be more poorly differentiated than the glottic tumour.

Besides the keratinising and non-keratinising squamous carcinoma, 2 special varieties of squamous carcinoma in the larynx are verrucous carcinoma (or Ackerman’s tumour) which is a variant of well-differentiated squamous carcinoma, and spindle cell carcinoma which has elongated tumour cells resembling sarcoma (pseudo sarcoma) at the other extreme of prognosis.

Cervical lymph node metastasis of laryngeal carcinoma is found in a good proportion of cases at the time of diagnosis.

Death from laryngeal cancer occurs due to local extension of growth into vital structures like the trachea and carotid artery; other causes are bacterial infection, aspiration

pneumonia, debility and disseminated metastases.

Diseases of the Larynx:

- Laryngeal papillomas are HPV-induced benign tumours.

- Laryngeal nodules or vocal polyps are composed of oedematous stroma and numerous irregular vascular channels.

- Laryngeal carcinoma is associated with smoking and is commonly squamous cell type.

Neck

Normal Structure:

The neck is the region from where important structures like the oesophagus, trachea, carotid arteries, great veins and nerve trunks pass through it.

Besides, the neck has structures such as a carotid body, sympathetic ganglia, larynx, thyroid, parathyroids and lymph nodes.

Only the tumours and cysts of the neck are considered here while the lesions pertaining to other anatomic structures are described elsewhere in the textbook.

Cysts Of Neck: The cysts of neck may be medial (midline) or lateral.

Medial (Midline) Cervical Cysts Thyroglossal Cyst: Thyroglossal cyst arises from the vestiges of the thyroglossal duct that connects the foramen caecum at the base of the tongue with the normally located thyroid gland.

The cyst is located in the midline, generally at the level of the hyoid bone, and rarely at the base of the tongue.

Microscopically, the cyst is lined by respiratory and/or stratified squamous epithelium.

Midline Dermoid Cyst:

A dermoid cyst located in the midline of the neck occurs due to the sequestration of dermal cells along the lines of closure of embryonic clefts.

The cyst contains paste-like pultaceous material.

Microscopically, it is lined by the epidermis and contains skin adnexal structures.

1. Medial (Midline) Cysts

- Thyroglossal cyst

- Midline dermoid cyst

2. Lateral Cervical Cysts

- Branchial (lymphoepithelial) cyst

- Parathyroid cyst

- Cervical thymic cyst

- Cystic hygroma

Lateral Cervical Cysts Branchial (Lymphoepithelial) Cyst: Branchial or lymphoepithelial cyst arises from incomplete closure of 2nd or 3rd branchial clefts. The cyst is generally located anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle near the angle of the mandible.

The cyst is 1-3 cm in diameter and is filled with serous or mucoid material.

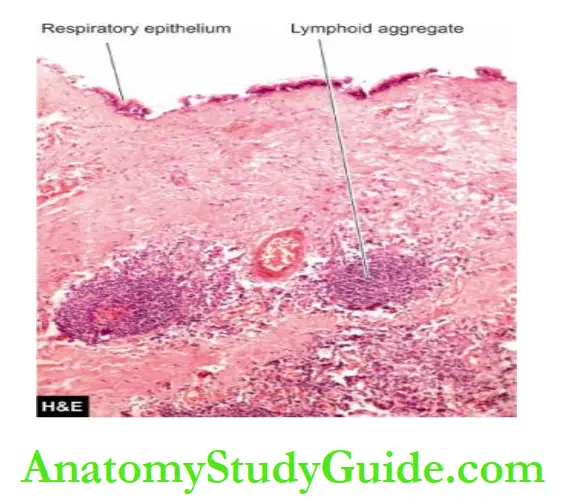

Microscopically, true to its name, the cyst has an epithelial lining, usually stratified squamous or respiratory epithelium, and subepithelial lymphoid tissue aggregates or follicles with germinal centres.

Parathyroid Cyst: Parathyroid cyst is a lateral cyst of the neck usually located deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the angle of the mandible.

These may be microscopic cysts or larger. They are generally thin-walled, and filled with clear watery fluid.

Microscopically, a parathyroid cyst is lined by flattened cuboidal to low columnar epithelium and the cyst wall may contain any type of parathyroid cells.

Cervical Thymic Cyst: Cervical thymic cyst originates from cystic degeneration of Hassall’s corpuscles. It is generally located on the left lateral side of the neck.

Microscopically, the cyst is lined by stratified squamous epithelium and the cyst wall may contain thymic structures.

Cystic Hygroma: Cystic hygroma is a lateral swelling at the root of the neck, usually located behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

It may be present congenitally or may manifest in the first 2 years of life. It is usually multilocular and may extend into the mediastinum and pectoral region.

Microscopically, cystic hygroma is a diffuse lymphangioma containing large cavernous spaces lined by endothelium and containing lymph fluid.

Tumours:

Tumours of the neck may be primary or metastatic in cervical lymph nodes.

Primary Tumours:

A few important examples of primary tumours in the neck are carotid body tumours, torticollis and malignant lymphomas.

Tumours of the thyroid, however, are discussed separately.

Carotid Body Tumour (Chemodectoma, Carotid Body Paraganglioma):

Carotid body tumour arises in the carotid bodies which are situated at the bifurcation of the common carotid arteries.

Carotid bodies are normally part of the chemoreceptor system and the cells of this system are sensitive to changes in the pH and arterial oxygen tension and are also the storage site for catecholamines.

Histologically similar tumours are found in other parasympathetic ganglia represented by the vagus and glomus jugulare (jugulotympanic bodies,).

Carotid body paragangliomas, as they are currently called, are rare tumours and occur between 3rd and 6th decades of life with slight female preponderance.

A few (5%) are bilateral and some show familial incidence. Grossly, they are small, firm, dark tan, encapsulated nodules.

Microscopically, well-differentiated tumour cells form a characteristic organoid or alveolar pattern, as is the case with all other neuroendocrine tumours.

The tumour cells contain dark neurosecretory granules containing catecholamines.

These tumours are mostly benign but recurrences are frequent; about 10% may metastasise widely.

Torticollis (Fibromatosis Colli, Wry Neck): This is a deformity in which the head is bent to one side while the chin points to the other side.

The deformity may occur as congenital torticollis or may be an acquired form.

The acquired form may occur secondary to fracture dislocation of the cervical spine, Pott’s disease of the cervical spine, scoliosis, spasm of the muscles of the neck, exposure to chill causing myositis, and contracture following burns or wound healing.

The congenital or primary torticollis appears at birth or within the first few weeks of life as a firm swelling in the lower third of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

The etiology is unknown but about half the cases are associated with breech delivery.

Grossly, the muscle is contracted, shortened and fibrous.

Microscopically, abundant dense fibrous tissue separates the muscle fibres.

Malignant Lymphomas: Various forms of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and Hodgkin’s disease occur in the cervical lymph nodes.

Secondary Tumours:

Cervical lymph nodes are a common site for metastases of a large number of carcinomas.

These include squamous cell carcinoma of the lips, mouth, tongue, larynx and oesophagus; transitional cell carcinoma of the pharynx and nasopharynx; thoracic and abdominal cancers such as of the stomach, lungs, ovaries, uterus and testis.

Diseases of the Neck:

Cysts in the neck may be midline (thyroglossal, dermoid) or lateral cervical (branchial, parathyroid, thymic, cystic hygroma).

The neck is the site for the primary carotid body tumours and various tumours of the thyroid.

Many metastatic tumours from several carcinomas in the head and neck, thoracic and abdominal viscera occur in cervical lymph nodes.

Leave a Reply