Gingival Involvement In Children Introduction

The gingiva in children exhibits significant changes during eruption and exfoliation of teeth. These are physiological changes.

Table of Contents

The gingiva may be involved in many pathologic conditions such as inflammation, enlargement, infections and neoplasm. They may also exhibit anatomic or developmental morphological defects.

The various conditions involving the gingiva of primary dentition are as follows:

- Physiological gingival changes with tooth eruption

- Simple gingivitis

- Gingival enlargement

- Chronic inflammatory enlargement

- Drug-induced enlargement

- Conditioned enlargement

- Puberty gingivitis

- Scorbutic gingivitis

- Plasma cell gingivitis

- Idiopathic enlargement

- Combined enlargement

- Viral and bacterial infections

- Cysts and reactive lesions

- Neoplasm

Read And Learn More: Paediatric Dentistry Notes

Physiological Gingival Changes With Tooth Eruption

Significant changes occur in the gingiva during the eruption of permanent teeth. These changes are distinct from gingival disease. Normally, before the eruption of a permanent tooth, the gingiva exhibits a bulge. The mucosa is pink or blanched and the film corresponds to the bulbous crown of the erupting tooth.

A prominent marginal gingiva commonly surrounds an actively erupting tooth. It can be more evident in the maxillary anterior region. This prominence of the marginal gingiva is called a pre-eruptive bulge. It is caused by the prominent height ofcontourofthe erupting tooth and mild inflammation due to mastication.

These physiologic changes may be secondarily involved due to poor oral hygiene. They may manifest into simple gingivitis or chronic inflammatory enlargement. Apart from these, there are two significant conditions involving the gingiva during the eruption of teeth. They are eruption cysts and pericoronitis.

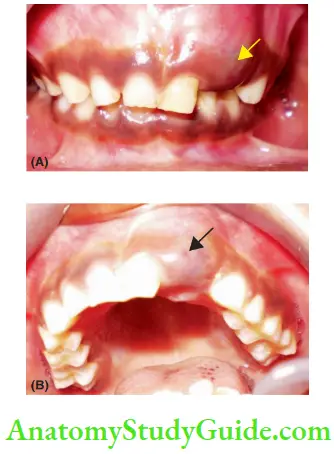

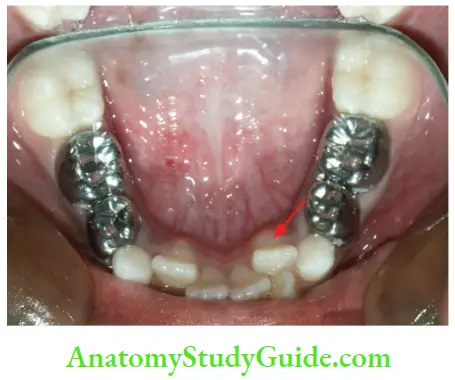

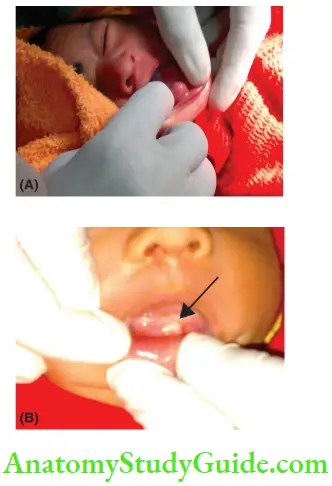

- Eruption Cyst Occasionally, bluish discolouration is seen on the gingiva over an erupting tooth. This is referred to as an eruption cyst. An eruption cyst implies that the erupting tooth is obstructed partially or totally by some pathology. It is different from the pre-eruptive bulge mentioned earlier. It is associated with over-retained primary teeth and delayed eruption of the permanent tooth. On the other hand, a pre-eruptive bulge signifies an erupting tooth with no obstruction or hindrance. Both pre-eruptive bulge and eruption cyst may sometimes occur simultaneously on the same tooth region. Eruption cysts are common in the permanent first molar region. It also occurs in the regions of succedaneous teeth whose predecessors have been lost prematurely, commonly mandibular permanent incisors. The eruption cyst may also be filled with blood. If so, it manifests as a dark blue or dark red gingival enlargement on the crest of the ridge. The eruption cyst either resolves spontaneously or requires marsupialisation as the mode of intervention.

1. (A) Eruption cyst associated with erupting left central incisor, succedaneous to the premature loss of primary lateral incisor.

2. (B) A more clear view of the same case.

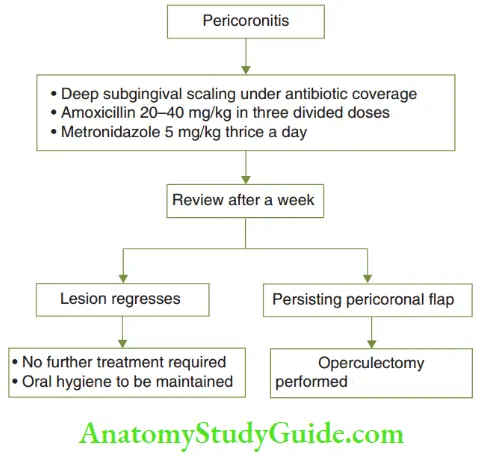

- Pericoronitis is the acute inflammation of the gingiva around an erupting tooth. It is more common in the first permanent molar region. It manifests as a flashy gingival flip over an erupting tooth, which is tender and has an increased tendency to bleed. Sometimes, it may become severe to extend into tissue spaces. The treatment may be oral prophylaxis under antibiotic coverage. If the lesion persists after a week, operculectomy has to be performed.

Simple Gingivitis

Simple gingivitis or gingivitis is a chronic inflamed tory involvement of the gingival tissues with no apical migration of junctional epithelium (loss of gingival attachment). It is the result of the response of the gingival tissue to the plaque microbiota at and below the gingival margin. The marginal gingiva and the interdental papilla are almost always involved in simple gingivitis.

Gingivitis is demonstrated within hours of plaque accumulation. It can be identified histologically in the initial stages. Non-removal of plaque and its subsequent build-up flares up this histological demonstration to a level where it can be demonstrated clinically.

Clinical Features The clinical manifestations of gingivitis include erythema, bleeding on probing, bleeding on brushing and gingival oedema. Simple gingivitis is less prevalent in children less than 4 years due to three factors, which are as follows:

-

- Less plaque content in the gingiva of children

- Less bacterial composition in plaque

- Less reactive host response gingiva to plaque

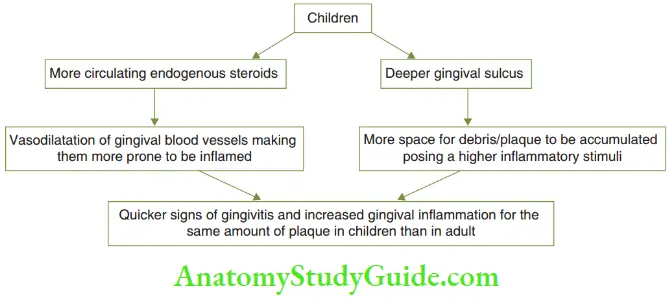

Prevalence increases from 50% in 4–5 years and goes up to 100% at puberty and declines thereafter. Gingivitis peaks at 11–12 years in girls and 11–13 years in boys. Signs of gingivitis arise quicker in children than in adults.

For the same amount of dental plaque, the associated gingival inflammation is relatively more in children than in adults. The possible reasons could be higher quantities of circulating endogenous steroids and increased depth of the gingival sulcus.

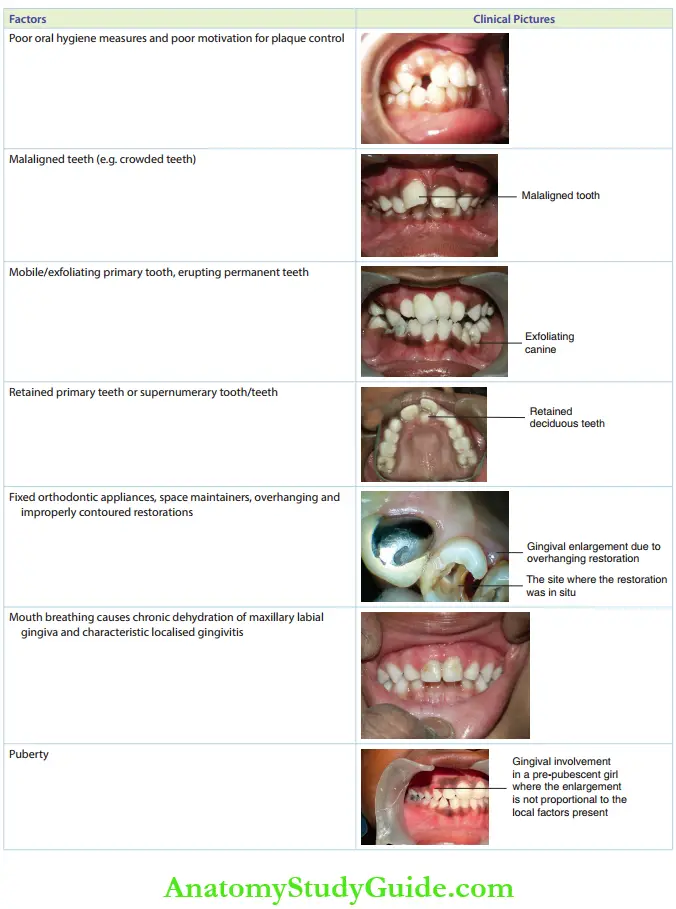

Predisposing Factors The factors that predispose the child to simple gingivitis are essentially the factors that favour plaque accumulation. These are listed in Table.

Treatment Simple gingivitis is reversible on the re-establishment of good oral hygiene. Professional oral prophylaxis is recommended. Elimination or intervention of the predisposing factor and oral hygiene instructions to the child are essential supplements to prophylaxis.

Simple gingivitis with plaque accumulation existing over a period of time associated with non-removal of predisposing factors (mentioned earlier) can lead to gingival enlargement.

Gingival Enlargement

Gingival enlargement implies an overgrowth of the gingiva that alters its size, contour and coherency of architecture corresponding to the cervical line of the associated tooth. The enlargement may be chronic inflammatory, drug-induced or conditioned enlargement.

- Chronic inflammatory enlargement: This arises from untreated, long-standing simple gingivitis.

- Drug-induced enlargement: This may be induced with the chronic use of certain drugs.

- Conditioned enlargement: This arises during conditions such as puberty and vitamin deficiency.

- Idiopathic enlargement: This is a non-inflammatory type of gingival enlargement.

The gingival enlargement may be a combination of one or more of the factors given earlier.

- Chronic Inflammatory Gingival Enlargement Chronicinflmmationofgingivaarisesdueto untreated, persistent simple gingivitis. This may in turn be due to long-standing plaque accumulation.

- Clinical Features Chronic inflammatory gingival enlargement may be localised or generalised. The marginal gingival and interdental papilla are enlarged, engorged and have a shiny erythematous appearance. The engorged gingiva is sensitive but need not necessarily be tender. The gingiva tends to bleed easily.

- Treatment This enlargement resolves by removing local factors such as plaque and calculus and predisposing factors such as malposed tooth and overhanging restoration. Institution of effective plaque control measures, good oral hygiene practices and removal of the predisposing factors for gingivitis can prevent a recurrence. When untreated, the magnitude of the enlargement grows exceedingly. It results in gingival recession an localised loss of the supporting bone of the involved tooth/teeth. When inadequately treated, that is removal of local factors (plaque and calculus) but non-intervention of predisposing factors (malposed tooth and overhanging restoration), recurrence is quicker.

- Clinical Features Chronic inflammatory gingival enlargement may be localised or generalised. The marginal gingival and interdental papilla are enlarged, engorged and have a shiny erythematous appearance. The engorged gingiva is sensitive but need not necessarily be tender. The gingiva tends to bleed easily.

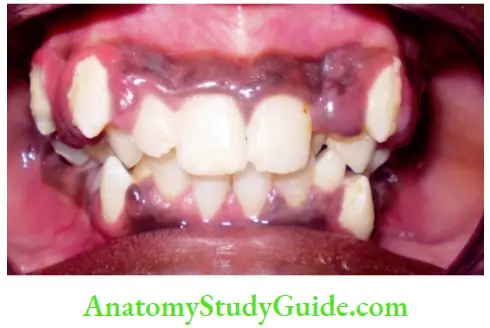

- Drug-Induced Gingival EnlargementGingival enlargement may be induced due to the chronic use of certain systemic medications. The induced enlargement is non-inflammatory in nature. Drugs such as phenytoin (anticonvulsant), cyclosporine (immunosuppressant) and nifedipine and nitredipine (calcium channel blockers) are known to cause gingival enlargement. While other drugs are being slowly replaced by newer synthetics, phenytoin does not have substitutes. Hence, phenytoin-induced gingival enlargement has been discussed specifically.

- Phenytoin-Induced Gingival Overgrowth The term ‘enlargement and overgrowth’ can be used synonymously in this case. Phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth or PIGO was first reported by Kimball in 1939. Earlier, it was referred to as ‘dilantin hyperplasia’. Now, it has been identified as overgrowth and not hyperplasia. There is no increase in the number or size of either fibroblasts or excessive collagen per unit of gingival tissue. Hence, it is simply called an overgrowth.

- Clinical Features The prevalence of PIGO in patients using phenytoin ranges from 0% to 95%. All patients on phenytoin need not necessarily incur overgrowth. The incidence and magnitude of the overgrowth depend on the following two factors:

- The dosage of phenytoin per unit body weight and the subsequent phenytoin levels in serum and saliva.

- Oral hygiene maintenance The incidences of overgrowth can be averted or the magnitude of the overgrowth can be kept to a minimum with meticulous oral hygiene practices and scrupulous oral prophylaxis.

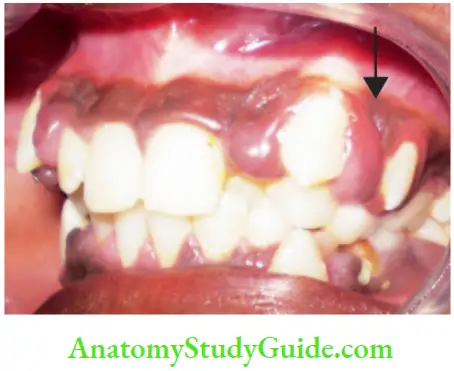

- The drug-induced overgrowth (PIGO, more specifically) appears as early as 2–3 weeks of inciting medication and reaches its peak by 18–24 months. The overgrowth is fim, pale pink and fibrous with little tendency to bleed. It starts at the interdental papilla and spreads to the gingival margin. The manifestations are initially isolated and later become generalised. Clinically, the overgrowth is more pronounced in the labial and anterior segments rather than in the posterior and lingual segments. The mesial papilla and distal papilla overgrow to demonstrate lobulations. These lobulations coalesce over the midline of the tooth to form a pseudo-pocket. The pseudo-pocket seems to bury the tooth. There is a possibility of this film overgrowth to be secondarily inflamed and/or infected. It, then, manifests as a tender overgrowth with a very high bleeding tendency. The secondarily inflamed gingival enlargement will carry a bluish hue signifying chronic venous stasis.

- The drug-induced overgrowth (PIGO, more specifically) appears as early as 2–3 weeks of inciting medication and reaches its peak by 18–24 months. The overgrowth is fim, pale pink and fibrous with little tendency to bleed. It starts at the interdental papilla and spreads to the gingival margin. The manifestations are initially isolated and later become generalised. Clinically, the overgrowth is more pronounced in the labial and anterior segments rather than in the posterior and lingual segments. The mesial papilla and distal papilla overgrow to demonstrate lobulations. These lobulations coalesce over the midline of the tooth to form a pseudo-pocket. The pseudo-pocket seems to bury the tooth. There is a possibility of this film overgrowth to be secondarily inflamed and/or infected. It, then, manifests as a tender overgrowth with a very high bleeding tendency. The secondarily inflamed gingival enlargement will carry a bluish hue signifying chronic venous stasis.

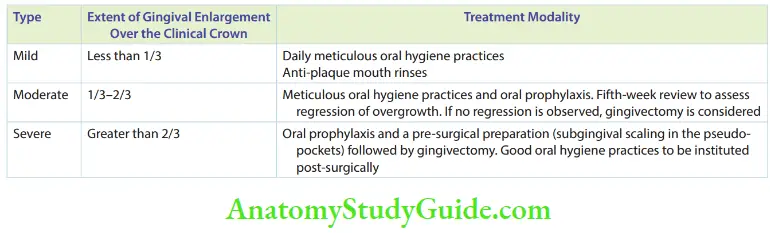

- Treatment The drug-induced enlargement resolves to a certain extent on discontinuation of the specific drug. The overgrowth may be graded as mild, moderate or severe. Their corresponding management is described in Table.

- A surgical mode of treatment is required in the case of severe overgrowth. It is also indicated if moderate overgrowth does not regress with oral prophylaxis in 5 weeks. The procedure indicated to remove the overgrowth is gingivectomy. It can be done by surgical mode, electrosurgery or laser surgery.

- Gradual overgrowth is quite expected post-surgically. If the overgrowth occurs almost insidiously after surgical removal, the dentist can discuss with the physician to consider the possibility of alternating the drug. The dentist, however, cannot direct the patient to discontinue the drug.

- Conditioned Enlargement Conditioned enlargement occurs in children in whom there is a demonstrable alteration of their systemic status or their gingival response to plaque. Puberty causes a high level of steroid hormones and alters the systemic status of an individual. Scurvy is caused due to vitamin deficiency, where collagen synthesis and gingival response are impaired on local irritation. Although local irritants and plaque are required to initiate the enlargement, the amount of plaque may be too less or disproportionate to the magnitude of enlargement. The gingival response may be exaggerated. The types of conditioned enlargement are puberty gingivitis, scorbutic gingivitis and plasma cell gingivitis.

- Puberty Gingivitis A distinct, chronic inflammatory type of gingival enlargement is demonstrated in circumpubertal adolescents. The high level of circulating corticosteroid hormones, during pre-pubescence or pubescence, increases the vascular permeability of the gingiva and alters its pattern of microbial interaction. This causes a distinct enlargement described as puberty gingivitis.

- Clinical Features The enlargement is usually found in the anterior segment or pertains to a single arch. The lingual gingiva is unaffected. Enlargement involves the marginal gingiva. The interdental papilla manifests as a bulbous overgrowth, especially in the presence of local irritants.

- Treatment comprises a prophylactic and a surgical phase:

- Prophylactic phase: Oral prophylaxis is done to remove all the local irritants. Oral hygiene is maintained meticulously.

- Surgical phase: It is indicated when the overgrowth fails to regress with local prophylactic therapy. Gingivoplasty of the thickened marginal gingiva and the bulbous interproximal area is performed. Spontaneous remission can be expected after puberty if all local irritants are removed and good oral hygiene is maintained.

- Scorbutic Gingivitis Scorbutic gingivitis arises in response to scurvy, the nutritional deficiency of vitamin C in children. In the vitamin C deficiency, there is enhanced capillary fragility with notable degeneration of capillaries. The endothelium of the capillaries swells and vessel walls become weakened, porous and haemorrhagic. The terminal capillaries and those capillaries that possess extensive anastomoses are highly prone to this degeneration. The reason why gingival capillaries are specifically involved is that they are terminal capillaries and possess extensive anastomoses as well.

- Clinical features Marginal gingiva and interdental papilla are involved. The affected gingiva appears bluish-red, soft and shiny. Gingiva is extremely friable and bleeds even on the slightest provocation, although not significantly tender. The interdental papilla is devoid of blood supply and demonstrates infarct tissue. These infarcts cause halitosis and may have a pseudomembrane.

- Treatment consists of two phases, both of which have to be performed simultaneously.

- Nutritional supplements: 250−300 mg of vitamin C should be taken as an oral daily dose. The child should be motivated to consume foods rich in vitamin C such as citrus fruits and citrus fruit juices.

- Oral prophylaxis: Thsisperformedinmultiplevisits as the gingiva bleeds extensively. On completion of oral prophylaxis, strict oral hygiene practices should be advocated.

- Gingivitis mostly disappears with no recurrence until the daily minimum intake level of vitamin C is maintained.

- Plasma Cell Gingivitis This acute type of gingival inflammatory enlargement is an allergic response to certain drugs. Discontinuation of specific drugs and antihistaminics can reverse the enlargement.

- Idiopathic Enlargement Fibromatosis gingivae or idiopathic gingival enlargement is a non-inflammatory type of gingival enlargement. The manifestations are similar to the drug-induced type. There is no demonstrable aetiology, but a genetic predisposition exists.

- A series of gingivectomies are required to aid in the eruption of permanent teeth and prevent them from being buried in the gingiva. Pseudo-pockets are prone to plaque accumulation. Hence, it is important to prevent secondary inflammatory involvement. Recurrence can be expected.

- Combined Enlargement Drug-induced gingival enlargement and idiopathic gingival enlargement can lend to a high degree of plaque accumulation as they present with pseudopockets. When oral hygiene measures are not adequate, a secondary enlargement occurs. The gingiva appears more reddish and engorged, with an increased tendency to bleed. This is a combined gingival enlargement as drug and local factors or predisposition and local factors combine to manifest the condition.

Infections

Viral and bacterial infections may affect the gingiva. The only clinically predominant viral infection with intraoral manifestations in children is herpes virus infection. Necrotising ulcerative gingivitis is the most common bacterial lesion of the gingiva in children.

- Herpes Virus Infection Herpes virus type I causes two patterns of oral infection in children – a primary lesion and a secondary (reactivated) lesion. The primary lesion is demonstrated at the time of viral inoculation in children. It usually happens within 5 years of age.

- Clinical Features Th viral inoculation may present in the following three types:

- Subclinical infection: 99% of herpes viral inoculation manifests subclinically. There is an absence of a distinct symptom or discomfort to the child.

- Mild sores on the oral mucous membrane: Sometimes, the symptoms of primary herpes infection may be limited to the occurrence of a few mild sores on the oral mucous membrane. There may be subtle discomfort, which may go unnoticed by the child or parents.

- Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis: The primary infection is manifested by acute symptoms that develop suddenly. The attached gingiva is the most affected tissue. The acute symptoms include the presentation of a fiery red attached gingiva, malaise, irritability and excessive discomfort while taking solid food and liquids with acid content.

- These manifestations are accompanied by a high fever, spiking to 104°C at times, and cervicofacial lym lymphadenopathy (usually submandibular lymph node).

- A characteristic finding is the presence of small flid-filed vesicles of diameter 1–3 mm. These vesicles eventually rupture to form ulcers covered with a whitish-grey membrane. These ulcers are common in the buccal mucosa, tongue, lips, hard and soft palate and tonsillar areas. The symptoms run a course of 10−14 days and heal eventually leaving no scar.

- Primary herpetic infections are characterised by a fourfold increase in the serum titre of antibodies to HSV-I. Viral culture is possible from the lesions. The initial primary lesions fade away.

- The organisms become inactive for a period of time. They become latent in the sensory nerve ganglia. When the host experiences an immune compromise, that is when the host is susceptible to infections, the inactive virus gets reactivated. When reactivated, it presents a recurrent HSV-I infection.

- It presents as ‘cold sores’ on the lip. This lesion is called recurrent herpes labialis.

- Treatment The treatment of acute herpetic gingivostomatitis consists of antiviral therapy and symptomatic relief.

- Antiviral therapy

- Systemic acyclovir 15–30 mg/kg body weight in five divided doses for a week is the antiviral regime for acute herpetic gingivostomatitis.

- A topical 5% acyclovir ointment is ideal as a topical antiviral drug.

- Symptomatic therapy

- Topical local anaesthetics, such as 4% lignocaine with choline salicylate, obtain good local anaesthesia and can be advocated for about six times a day.

- Rehydration of the child with plenty of fluids.

- Antiviral therapy

- Clinical Features Th viral inoculation may present in the following three types:

- Necrotising Ulcerative Gingivitis Necrotising ulcerative gingivitis is a bacterial infection caused by Borrelia vincentii and Fusiform bacillus. It is also referred to as a fusospirochetal infection. This lesion usually presents in the 6–12 years age group and is associated with poor oral hygiene.

- Clinical Features The clinical manifestations are limited to the marginal gingival and interdental papilla. The marginal gingival exhibits zones of redness and inflammation, bleeding tendency, tenderness and necrosis. The interdental papilla exhibits punched lesions depicting necrosis of tissue. The necrosed areas are covered by a pseudo-membrane. Fetid odour (necrosis), general malaise and loss of appetite are other symptoms.

- Treatment comprises debridement of necrosed areas, use of mild oxidising solutions (bactericidal to this pathognomic flora), oral prophylaxis, subgingival curettage and meticulous oral hygiene instructions.

Cysts And Reactive Lesions

The most common cysts found in children are palatal cysts and pyogenic granuloma. Pyogenic granuloma can be described as a reactive lesion as the tissue

undergoes regeneration due to a stimulus or irritant. The two lesions are discussed next.

- Palatal Cysts Of The Neonate Palatal cysts of the newborn (neonate) are true inclusion cysts appearing in clusters. The cysts are small, raised white nodules, measuring upto 3 mm in diameter. The clusters are called Bohn’s nodules or Epstein pearls depending upon their location.

- Bohn’s nodules: They appear between the junction of the hard and soft palate.

- Epstein pearls: They appear at the mid-palatine raphe.

- These inclusion cysts are true cysts lined by a layer of compressed stratified squamous epithelium with the lumen containing keratin. These cysts are considered as a normal feature and are reported to be present in 80% of the neonates.

- They enlarge with time, contact the overlying epithelium and undergo self-marsupialization to heal uneventfully. Hence, they require no treatment.

- Pyogenic Granuloma Any tissue when subjected to an irritant or stimulus undergoes degeneration or regeneration. Pyogenic granuloma is an example of the latter. It manifests as a result of a low-grade, non-specific infection in a host with exuberant local immunity. The low-grade infection acts as the stimulus to induce an overzealous growth of the tissues locally. The exuberant growth resembles typical colonies of saprophytic organisms.

- Pyogenic granuloma commonly occurs in the intraoral region. It runs an abrupt clinical course to quickly attain a considerable size. It commonly manifests on the gingiva. It is found less commonly on the lips, tongue and buccal mucosa. The lesion is raised, soft smooth and lobulated. It has intact or ulcerated skin, which is deep red or reddish-purple in colour. The lesion is painless but has an intense tendency to bleed (haemorrhagic).

Neoplastic Lesions

The most common neoplastic lesions affecting the gingiva of children are congenital epulis and peripheral ossifying fibroma (POF). These are discussed in the following text.

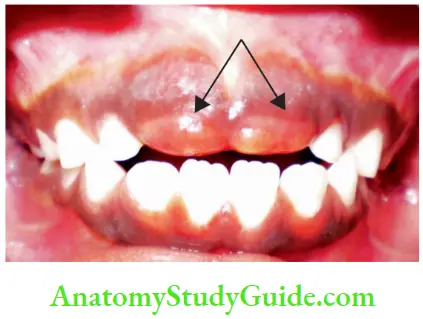

1. (A) Epulis found on the anterior mandibular gingiva.

2. (B) Lesions excised and uneventful healing seen by the fourth day

- Congenital Epulis Of The Newborn Congenital epulis of the newborn is a soft peduncle late, a benign outgrowth of the gingiva, most commonly found on the crest of the alveolar ridge. It is commoner in newborn girls and three times more common in the maxilla. The anterior alveolar ridge is a more common site than the posterior alveolar ridge.

- It may vary from a few millimetres to 9 cm (largest size reported) in size.

- Clinically and histologically, the lesion resembles granular cell myoblastoma. Clinically, granular cell myoblastoma is more common on the tongue and it is an early developmental lesion rather than congenital.

- Histologically, congenital epulis shows sheets of closely packed large cells with fine granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and numerous capillaries. On the contrary, pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia is seen in myoblastoma with a poor vascular network. The figure shows a case of congenital giant cell epulis in a newborn female baby.

- The epulis, found in the anterior mandibular gingiva, measured 15 × 20 × 15 mm3. The lesion was excised surgically. Uneventful primary healing is seen within 4 days. Surgical excision is the treatment mode. Recurrences are rare.

- Peripheral Ossifying Fibroma Peripheral ossifying fibroma is a relatively common gingival lesion (outgrowth). It is often associated with trauma or local irritants such as subgingival plaque and calculi, dental appliances and poor-quality dental restorations. POF is characterised by a high degree of cellularity usually exhibiting intralesional bone formation of cementum-like material occasionally and dystrophic calcification rarely. POF is odontogenic in origin and is derived from the periodontal ligament. It occurs only on the gingiva and may contain xylan fires.

- Clinical Features POF can occur at any age although it appears to be more common in children and young adults. 50% of the lesions occur between the ages of 5 and 25 years with the peak incidence at 13 years, while the mean age being 29 years. A series of reported cases show a female predilection. 80% of the lesions are found in the incisor to the molar area. In addition, the lesions are equally divided between the maxilla and mandible.

The clinical appearance of the lesion is characteristic but not pathognomonic. Although lesions of the size of 9 cm have been reported, they are generally less than 2 cm in diameter. It is a well-demarcated, focal mass of tissue on the gingiva with a sessile or pedunculated base.

It is of the same colour as the normal mucosa or slightly reddened. The surface may be intact or ulcerated. It most commonly appears to originate from the interdental papilla.

In the majority of cases, there is no apparent underlying bone involvement. However, rarely, superficial erosion of bone occurs. Recurrences of the lesion on surgical excision are uncommon.

Summary

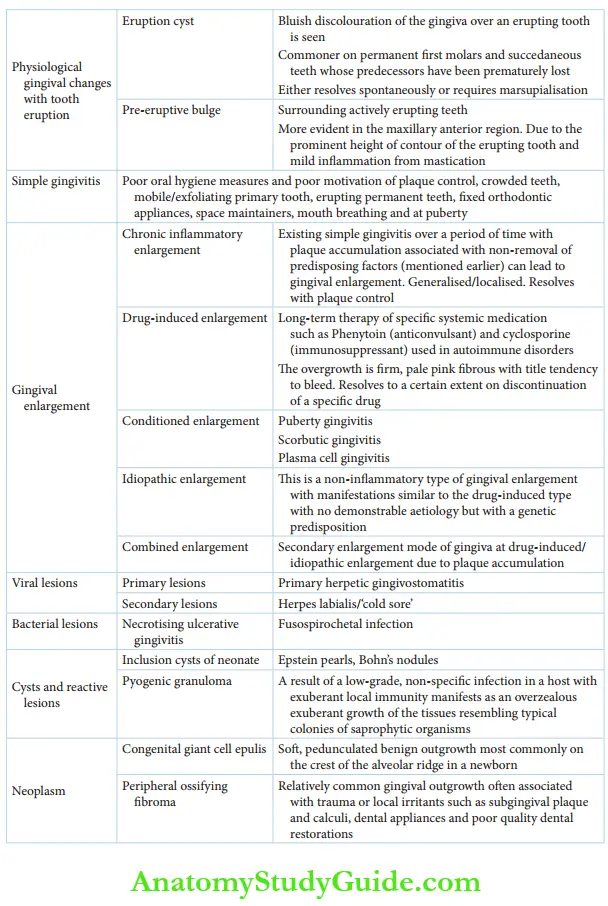

Gingival involvement in children is summarised as follows:

Leave a Reply